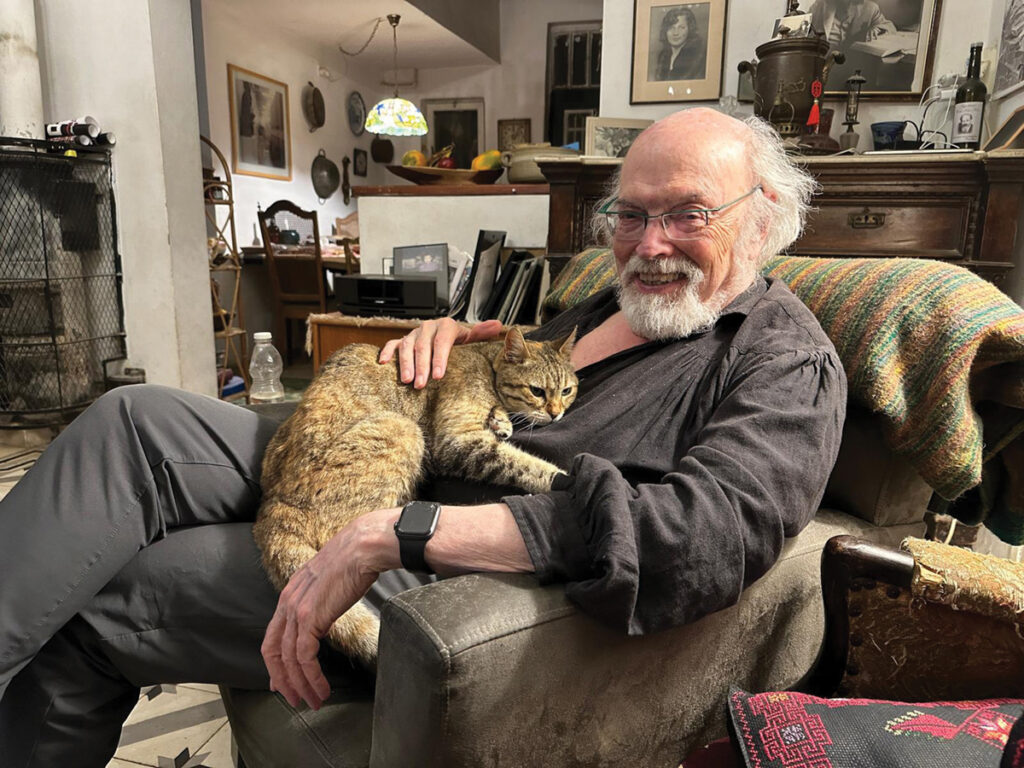

“As Long as You’re Healthy”: Paul Mendes-Flohr (1941–2024)

Born during the Second World War, Paul Flohr grew up in the hardscrabble Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn and spent his summers at Kinderland, a socialist camp tucked into the Berkshires. At camp, he learned the rudiments of baseball—taught, improbably, in Yiddish. “I suppose that explains why I never mastered the sport,” he later joked. At eighteen, volunteering at a kibbutz in northern Israel, he first encountered the teachings of Martin Buber, which he would spend the rest of his life mastering. At the time, he said with characteristic self-deprecation, “I didn’t understand a word.”

In an unpublished memoir he shared with me, Paul recalled his mother’s understated tenderness when he brought home his first-grade report card from P.S. 167:

Downplaying its significance, my mother reassuringly told me: “As long as you’re healthy.” What came across, as if by osmosis, was her desire to protect me from the competitive ethos of American culture. She wanted me to be cultured, but never pushed me to excel, “to become somebody.” Neither she nor my father ever evaluated people by their social status and attainments.

Paul grew up in the close quarters of his father’s candy store, where he washed dishes, arranged newspapers, served sweets, and made ice-cream cones. The family scraped by on a single meal each day, a deprivation that, years later, would leave its silent mark: X-rays taken during a hospital stay in Chicago revealed the signs of childhood malnutrition in his legs.

Paul recalled singing a mischievous ditty with friends that, as he realized only later, expressed his wish to rescue his mother—a cosmopolitan woman who spoke Russian, Yiddish, Italian, and English—from the humdrum confinements of that shop:

My father had a candy store.

Business was so bad,

I took a can of kerosene, spilt it on the floor,

fetched a match, made scratch,

no more candy store!

The wish went unfulfilled. Paul’s mother was beaten outside the store one Saturday night by neighborhood toughs who had stolen a bundle of newspapers; she suffered a heart attack and died in the hospital corridor where she had been left untreated because she lacked health insurance. Paul, only twenty-four, delivered her eulogy—his first time speaking publicly. He spoke of the way his mother “related to each and every one of our customers as sheyne yidn, as fellow human beings each graced with a uniquely beautiful soul.” Paul later realized that his mother’s respect for the intrinsic dignity of every human being had exerted “a subliminal influence on my later affinity to Martin Buber’s teachings.”

After graduating from Brooklyn College, Paul went to graduate school at Brandeis University, where he met his future wife, Rita Mendes, and three mentors who profoundly shaped his life. Nahum N. Glatzer, who had studied with Franz Rosenzweig and written his doctoral dissertation under the supervision of Buber, taught the young apprentice that “scholarship is a craft”—one that must be taught by example. Looking back at his time with Glatzer more than half a century later, Paul wrote:

Like the hasid who learns what is holiness by beholding how his master ties his shoes, we—who were privileged to be his students—learned what genuine scholarship entails through the very person of Professor Glatzer; his bearing and manner of pursuing knowledge introduced us to the ethos and calling of the scholar.

Alexander Altmann, Paul’s second adviser, exulted over his first paper with the words, “Fussnoten! Wunderbare Fussnoten!” Beyond an appreciation for the gravity of a well-placed footnote, Paul learned from Altmann “that the life of the mind is the quest for spiritual integrity. … At the very first class I took with him, I was so utterly enthralled by his evocation of the poetic interiority of ideas that I let the tears flow.”

His third guide, Ben Halpern, gave Paul “what Buber called Bewährung, the confirmation of one’s unique being independent of societal and institutional conceptions of self-worth.” This “troika of inestimable mentors,” as he called them, listened as much to Paul’s silences as to his words. “By honoring my silence,” he said, “they also encouraged me—nurtured my courage—to listen and honor my own voice, chiseled in my life-experience and in the murmuring of my soul.”

In 1968, Paul arrived in Berlin to write a dissertation on Buber. He carried a letter of introduction from Altmann to Jacob Taubes, director of the Freie Universität Institute for Jewish Studies, who gave the “diffident twenty-seven-year-old” his first teaching position. From Berlin, Paul went to Jerusalem, where he developed a “spiritual bond” with Buber’s son and literary executor Rafael. “I had become his confidant—indeed, an adopted son. Whenever the phone would ring at home, our daughter Inbal would bemusedly exclaim, It must be Buber!”

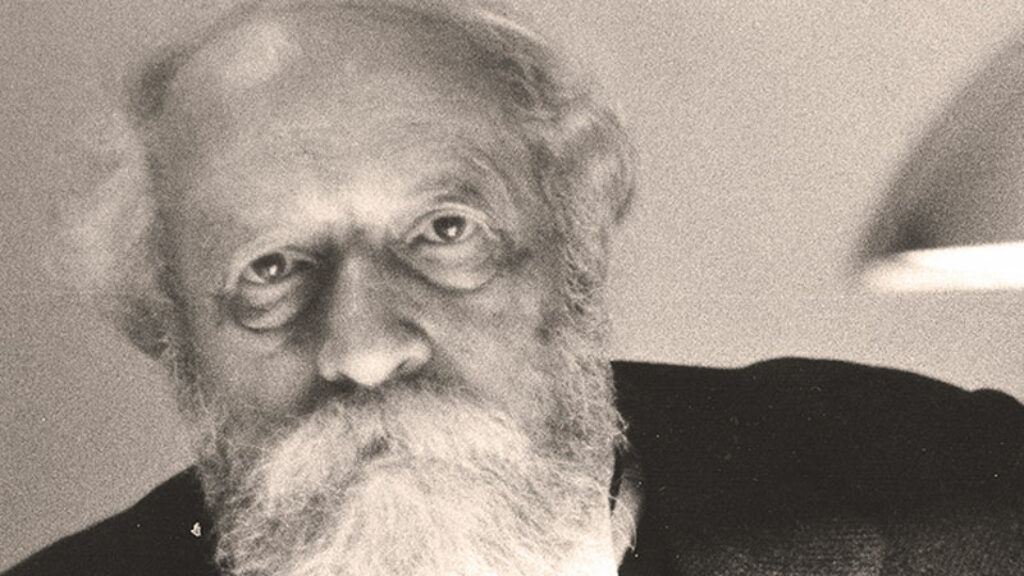

At Rafael’s invitation, Paul gathered Buber’s letters, talks, and essays on Zionism, which appeared as A Land of Two Peoples (1984). (A revised edition, with a new foreword, is scheduled for publication this spring.) Over the next decades, Paul’s scholarship embodied Buber’s beliefs that “all real living is meeting” and that we experience God’s presence refracted through the human beings we directly come to know. From Mysticism to Dialogue (1989), an expanded version of his dissertation, remains the definitive work on the evolution of Buber’s thinking. Together with Glatzer, he edited a collection of Buber’s voluminous correspondence. Alongside Peter Schäfer and Bernd Witte, he coedited a monumental twenty-one-volume German critical edition of Buber’s collected works—a feat that demanded decades of meticulous labor and a reverence bordering on love.

But Paul was no hagiographer. In his 2019 biography, Martin Buber: A Life of Faith and Dissent, he portrayed Buber unflinchingly. “Scarred by the wounds of a troubled childhood,” Paul wrote, “he was at times narcissistic and self-absorbed. . . . Buber was not a perfect human being—although he was perfectly human.” Paul renders Buber not as a prophet (as in earlier biographies by Hans Kohn and Maurice Friedman) but as a man of profound contradictions whose “Hebrew humanism” collided painfully with the harsher realities of the twentieth century.

Like Buber, who collected Hasidic parables and tales, Mendes-Flohr was a prodigious anthologizer. Together with his friend Jehuda Reinharz, Halpern’s student and successor at Brandeis, Paul published The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History in1980, which has gone through three editions and become the standard in the field. Not long after, he was talking with his friend, the publisher, theologian, and novelist Arthur A. Cohen, at the American Colony Hotel about “the alleged Jewish disinclination to engage in theology.” Their conversation eventually yielded Contemporary Jewish Religious Thought, a sweeping 1,200-page collection of 140 essays. In 1987, he coedited a groundbreaking collection of essays, Judaism and Christianity under the Impact of National Socialism, with Otto Dov Kulka.

A couple of years ago, I invited Paul to write for Sources, a journal I edited. His essay, “Why Is America Different?” closes with a call for American Jews to sing “a robust song of thanksgiving” for the country’s pluralistic promise, while keeping a watchful eye on its failings. Paul likewise held out hope that some of the healthier spiritual sensibilities of the Zionist vision, however dimmed by contemporary Israeli ideological inclinations, could yet be revived and that the “re-ghettoization of the Jews,” as he put it, could yet be reversed.

Buber, in his own words, had regarded Zion as “both a geographical and spiritual goal.” The choice to live in the Jewish state, Paul contended, is thus a decision “that not only does not exclude our universal sensibilities but deepens them.” He liked to quote from a letter addressed by Shmuel Hugo Bergmann, later the first rector of Hebrew University, to Franz Kafka: “My Zionism is an expression of my quest for love; because I am aware that thousands of others suffer as I do, I wish to join with them, to work with them—oh, if only I could, at least, feel with them.” At Paul’s funeral, a friend whispered: “He never met Buber, you know. But he didn’t need to. . . . He felt with him.”

I came to know Paul Mendes-Flohr over the last decade at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, where his genial, steadfast presence—“our perpetuum mobile,” a colleague called him—made itself felt in the library’s back row. Even years after he had retired from both the Hebrew University and the University of Chicago, Paul climbed daily from Emek Refaim to Van Leer, dignified in gait, as though he were escorted by Rabbi Tarfon’s adage: “It is not your responsibility to finish the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

Both Buber and Rosenzweig, Paul once wrote, “humbly invited us to listen in on their dialogue with God.” Over the last year, still listening in, Paul finished editing A Companion to Martin Buber and completed his biography of Rosenzweig, Love as Strong as Death, which had been in preparation for more than thirty years. (Both books are due out in 2025 from the University of Chicago Press.)

Paul died on October 24, Simchat Torah, at age eighty-three. He is survived by his wife, Rita; children, Inbal and Itamar; and grandchildren, Eden, Enosh, Tuval, and Avigail. One afternoon in the library, during one of our conversations, he let slip that Georg Simmel—the sociologist from whose teachings Buber drew his concept of dialogue—consoled students with the aphorism “thinking hurts” (Denken tut weh). So does losing a beloved friend, a soft-spoken master of his craft, a sheyner yid as attuned to the pain of others as to the murmuring of his own soul.

Suggested Reading

Israel’s Iron Lady

Golda told Nixon: “You are the president of 150 million Americans; I am the prime minister of six million prime ministers.”

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Remembering the Scholems

New books about Gershom Scholem and his brother Werner evoke memories of 28 Abarbanel Street in Jerusalem.

My Path in Jewish Studies: Memoirs of a Counter-Historian

When David Biale told Gershom Scholem that he wanted to work on the history of Jewish sexuality, the great sage of Jerusalem responded, "That's not a field!"

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In