Remembering the Scholems

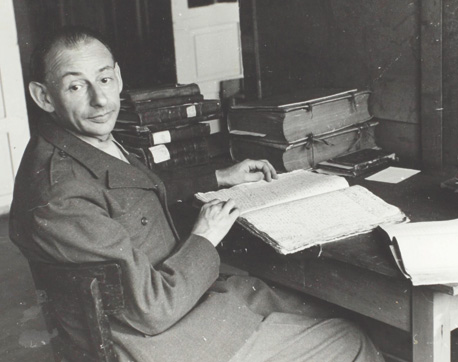

Among Israeli intellectuals of his generation, Gershom Scholem had by far the greatest impact both at home and abroad. At home, Geulah Cohen, the Joan of Arc of Lehi (the so-called Stern Gang), sat at his feet, but so, in the early years, had Berl Katznelson, the guru of the Labor Party, as had seemingly every other Israeli politician, writer, and scholar. By the time I was a regular guest at his home in the 1960s and 1970s, a visit to Scholem had become part of the program for visiting European and American intellectuals who came to Jerusalem for a week or two; there should have been signposts in Rehavia similar to those in other parts of the capital, guiding visitors to his book-lined home on 28 Abarbanel Street. (He would be pleased to know that streets are now named after him in Israel.)

It is not easy to explain the spread of Scholem’s fame. His field, the history of Kabbalah, was literally esoteric, and even if many intellectuals understood that the irrational had become inescapable in the 20th century, few had ever heard of the texts and figures Scholem worked on outside of the pages of his own books and essays, preeminently Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, let alone read them. Nonetheless, he had a deserved reputation not only as a genius who had almost single-handedly created an academic field, but also as someone who had profound things to say not just about Jewish history and Zionism, but also about philosophy, history, and politics. Moreover, given the nature of his expertise, along with his enormous self-confidence, he came to be thought of as a kind of magician. And though sometimes prickly, he liked company (and he liked to gossip), so the stream of distinguished visitors, invited visits abroad, and academic honors continued until his death in 1982.

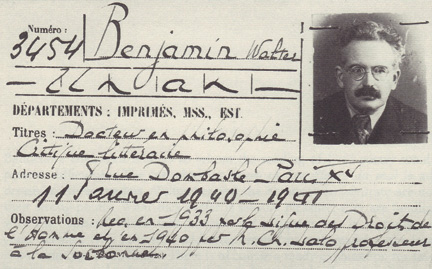

In the decades since then, the study of Scholem himself has become almost its own academic subfield—just this year there were international conferences devoted to him in Jerusalem and at Indiana University. Part of this is due to his relationships with other extraordinary German-Jewish intellectuals of his generation, especially the philosopher-critic Walter Benjamin. Throughout their friendship (which Scholem chronicled in a moving memoir, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship), he fought an uphill battle to get Benjamin interested in Jewish culture and even to come to

Israel. Preoccupied with messy love affairs, Baudelaire, his relationship with Bertolt Brecht, and Marxist theory, Benjamin didn’t get much further than learning the Hebrew alphabet, nor did he realize that the world around him was on fire until it was too late. He committed suicide on the French-Spanish border while trying to escape from Nazi-occupied France in 1940.

In 1941, Scholem dedicated Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism to his memory. For several decades now, Benjamin has been at least as celebrated a figure as Scholem himself, but that we know of him at all is one of Scholem’s achievements. He shares that credit with two of Benjamin’s other friends, Hannah Arendt and one of the leaders of the Frankfurt school of critical theory, Theodor Adorno, both of whom collaborated with Scholem in championing Benjamin’s works to skeptical publishers. This becomes clear in the recently published correspondence between Scholem and Adorno, which nicely complements the more famous correspondence between Scholem and Arendt, published in full in Germany five years ago (reviewed in these pages by Steven E. Aschheim, “Between New York and Jerusalem,” Winter 2011).

In both cases, the bulk of the correspondence is devoted to Benjamin, though, of course, the climax of the Arendt-Scholem letters was their famous public exchange over Eichmann in Jerusalem. History has, I believe, largely vindicated Scholem in his criticism of Arendt’s description of the Jewish councils in the camps and her application of the concept of “the banality of evil” to Eichmann (see most recently Bettina Stangneth’s Eichmann Before Jerusalem, and Richard Wolin’s review “The Banality of Evil: The Demise of a Legend,” Fall 2014). Nonetheless, in re-reading the exchange, it seems to me that Scholem was wrong or unfair in two matters. Contrary to Scholem’s allegations, Arendt did not turn to anti-Zionism under the influence of left-wing German-Jewish circles. She did write some foolish things at the time—for instance that the Zionists could learn from Soviet policy on national minorities—but, on this point, Scholem misread her. Arendt thought, rather, that Zionism had gone wrong in its nationalism just when the nationalist era had passed. She turns out to have been wrong about this, certainly outside of Europe, but it was not a Marxist (or marxisant) error. As for Scholem’s well-known complaint that Arendt lacked ahavat yisrael (love of Israel), it should be noted that though her descriptions of Galician and North African Jews were unkind, even racist, such language and attitudes had been common for a long time among Jews from Western Europe and Germany with regard to their Eastern coreligionists. And the attitude was often reciprocated.

Hannah Arendt was a strange mixture of contradictory qualities: warm-hearted and ready to be of help in an emergency, but also arrogant, given to exaggerated and premature judgments and remarks. Ironically, she shared some of these qualities with Scholem. But Scholem was always far more cautious in print, and this aspect of his personality was, consequently, less public. I remember a conversation in which he impressed on me that one could say almost anything in conversation but one had to be very careful with what one wrote. (This lesson arose not from any great issue that had been discussed but comments he had made about a fellow Jewish thinker, perhaps even more famous at the time than Scholem, who, he said, had a roving eye.)

It is well-known that Scholem was hostile to the Frankfurt School, whose members he regarded as deluded, both about the explanatory power of their eclectic brand of neo-Marxism and about their identities (virtually all the members of the school were Jewish; Adorno himself had a Jewish father and an Italian mother). He once mordantly described the group as a Jewish sect and deeply resented its power over Walter Benjamin. So one is surprised by the cordiality of his exchanges with Adorno. He didn’t think much of Herbert Marcuse, whose interpretations of Benjamin he once described as “insolent blabber,” but in this he and Adorno were in agreement. Accounts of their relationship may need to be slightly revised.

Three other new books have recently appeared (all of them in German, though Noam Zadoff’s biography first appeared in Hebrew) that shed further light on Scholem’s life, personality, and family. Zadoff’s book is the first (almost) full-scale biography. Its title, Von Berlin nach Jerusalem und zurück (From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back), is of course a play on the title of Scholem’s own memoir of his youth, From Berlin to Jerusalem. But it also points to the thesis of the author, which is that late in life Scholem became disillusioned with Zionism and pessimistic about the future of Israel. It is this disillusionment, according to Zadoff, that explains Scholem’s late-life involvement with so many German thinkers and

institutions, as well as why he spent so much of his time travelling abroad.

Zadoff has put his finger on a real biographical issue. After all, in 1964, Scholem had famously denied that there had ever been a “German-Jewish dialogue.” The idea of a true dialogue, or cultural symbiosis, had always been a chimera or, at best, a one-sided affair. The Jews had wanted to be Germans, but the Germans had never welcomed this aspiration. But if this remained Scholem’s position, why did he spend so much time back in Berlin, and other European capitals, not to speak of Jung’s Eranos Conferences in Switzerland? (Zadoff’s account of Scholem at Eranos is one of the highlights of the book.) Did he have a late-life change of heart and give up on his (admittedly idiosyncratic) brand of political Zionism for something more like a version of Ahad Ha-Am’s cultural Zionism?

In the late 1960s, when I was working on my history of Zionism, I asked George Lichtheim, a close mutual friend (and the translator of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism), to arrange an interview with Scholem. I was curious about how he had come to make aliyah in September 1923 when very few others came to Palestine from Central Europe. The historian S.D. Goitein, his future colleague at The Hebrew University, came from Germany at that time, but I doubt whether there were more than a dozen others—despite the ruinous hyperinflation of the time. His answer after a few seconds of deliberation was “I wanted to put an end to the wretched traditional Jewish passion for constant travel!” But, he said, “Look how I failed—they travel now more than ever.”

Scholem’s more serious answer was that he went to Jerusalem as a young man because he was convinced that Eretz Yisrael offered a chance—the only chance—for a revival of Judaism and a rebirth of the Jewish people. A conversation ensued that lasted off and on for more than a decade. I was a permanent visiting professor at Tel Aviv at the time, but we usually spent our weekends with our daughter in Jerusalem and would regularly visit Gershom and Fanya—even she addressed him as “Scholem”—on Shabbat afternoons.

Of course, Zadoff is right that Scholem was less enthusiastic and optimistic in the 1970s than he had been as an idealistic 26-year-old immigrant; there are many reasons for this, but one of them is simply that elderly people seldom are as enthusiastic as the young. Scholem moved to Jerusalem in pursuit of a utopian dream. Dreams sometimes come true, but hardly ever in the way one anticipated. There was indeed an ingathering of exiles, and a state came into being. But it was not built by those envisaged by Herzl and the early Zionists, since most of European Jewry had disappeared in the Holocaust. Seen in this light, a measure of disappointment, perhaps even great disappointment, was inevitable. But I don’t think that it drove Scholem back to a Berlin that no longer existed. What Scholem had told me about the Jewish proclivity for travel also turned out to apply to him.

A great many things attracted Scholem to Europe, not least the fact that he was admired there as one of the giants of the prewar intellectual generation. Jürgen Habermas, in whose house near Munich leading intellectuals often met when they came to Germany, describes how Adorno, Marcuse, and other leading thinkers not known for excessive modesty fell silent in Scholem’s presence. Scholem was, of course, flattered. Who would not have been? But this was genuine respect, not just intellectual Wiedergutmachung (restitution). Nor, I think, was Scholem escaping Jerusalem or trying to recapture a Berlin he had lost. Rather, he and other postwar intellectuals found themselves trying to recreate the old European “republic of letters,” in which scholars and thinkers moved freely from one country to another. There were many reasons for this too, but one of them was technology; improved communications and travel, not to speak of peace, opened up the world. The renewal of this intellectual tradition, together with the common desire of distinguished academics to travel on their laurels, rather than a love affair with Germany, seems to me sufficient explanation for Scholem’s perambulations.

Gershom, or rather Gerhard, was the youngest of the four Scholem boys; his brother Werner was nearest to him in age. Gershom was apparently their mother Betty’s favorite (even after he emigrated, she sent his favorite German chocolate to Jerusalem). No one caused her more heartache than Werner, who is, remarkably, now the subject of two enormously detailed biographies, one by Mirjam Zadoff (Noam Zadoff’s wife) and the other by Ralf Hoffrogge.

Politics was Werner’s great passion, but his political sense and, above all, his timing were terrible. Like Gershom, he began his political life in Jung Juda, a left-wing Zionist youth movement, just before World War I. After serving in the army (Gershom had feigned madness to avoid service), Werner became one of the leaders of the German communists in the early 1920s, but he quarreled with the Stalinists and became a Party outcast. In the 1930s he was, nonetheless, imprisoned by the Nazi regime as a communist, and, despite his family’s best efforts (after all, they argued, he had been expelled from the Party), he remained in prison and thus was not able to leave Germany with the rest of the family. He was murdered in Buchenwald, perhaps as the result of a denunciation by Communist fellow inmates, though of course his chances of survival were slim in any case.

Years ago, a strange, unpublished manuscript was given to me to assess. A poorly written and unlikely narrative entitled The Daughters of the General, it was the story of a young Jewish communist who had an affair with the daughter of a German general. The communist was working for the Soviet secret service, or the Cheka as it was then called, and induced the girl to obtain secret information from her father. The book had been written by the leader of one of the communist splinter groups of the time. Although none of it seemed very plausible, the young Jewish communist seducer sounded very much like Werner Scholem. Of course, I thought of asking Gershom, but refrained, since I doubted that he knew and, in any case, probably would not have told me if he did.

Some years ago the truth came out—the strange novel was not pure invention. The general was Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, head of the Reichswehr, the German army in pre-Hitlerian days. His daughters were communists, and Werner Scholem had indeed had an affair with one of them, Marie-Louise, when they were studying law at the University of Berlin together. However, the real Soviet spy had been another young Jewish communist named Leon Roth, originally a member of the Poalei Zion Marxist-Zionist movement. Marie-Louise was his spy, and he did obtain valuable information from her.

In February 1933, Hitler made a speech in the general’s apartment in which he told the assembled top brass about his war plans. Marie-Louise got a detailed account of the speech to Roth. Soon after, Roth was called to Moscow, but his intelligence won him no honors. Instead, like many other agents, he was shot. Stalin, needless to say, ignored the information.

After Scholem’s letters with his mother were published, I found out that he had, in fact, known about his brother’s affair. In a long letter from Italy in 1930s (in which she called Werner a “giant ass”), Betty told him the whole story. Had he told me, I could perhaps by strange coincidence have filled him in on a point or two. Some time after the war, at a London bus station, I ran into an old classmate named Gebhard. To cut a long story very short, he was the first husband of Werner Scholem’s daughter Renee. They too had been communists, members of a front organization called Free German Youth in London, and the party demands wrecked their marriage. (Renee eventually became an important executive at the BBC.)

As for Marie-Louise, it turned out that she was given the benefit of the doubt by the Gestapo, who decided that she had been the innocent victim of an intrigue. She survived the Nazi regime and became a lawyer in communist East Germany. One of her sons defected to West Germany. The awful novel I had read was finally published a few years ago in Berlin, but its story has inspired other, perhaps better, ones.

Gershom Scholem was an utterly unique individual if any one ever was, but his family exemplified much of the 20th-century German-Jewish experience (symbiosis or no symbiosis). I do not claim to understand him better than present or future historians because I sat in his house and drank Fanya’s coffee, but I do hear his voice again in these new and recent volumes, especially in his voluminous, sparkling correspondence.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Gray Lady and the Jewish State

Jerold Auerbach’s archly titled new study Print to Fit: The New York Times, Zionism and Israel, 1896–2016 is a well-researched and, for the most part, damning brief of the Times’s news coverage and editorial attitudes toward Zionism and Israel for over a century.

Homage to Mahj

A traveling exhibit attempts to explain the Jewish fascination with Mah Jongg, a favorite past-time of mid-century Jewish suburbia, Jewish country clubs, and Catskill resorts.

The Life of the Flying Aperçu

Dickstein’s story is not a narrative of apostasy and rebellion; belief and doctrine play a minor role.

What They Talk About When They Talk About Golems

On golems and global conspiracy theories.

mam4gladys

What a splendid brief reflection on Scholem. Perhaps one of the English speaking world's university presses will publish translations of these crucial volumes, incalculably more in keeping with their function than a vast amount of stuff they put out as credentials for the tenure process.