Include Me Out

When the $488 million Academy Museum of Motion Pictures opened in Los Angeles in September 2021 after what The New York Times called an “almost comical series of setbacks,” its organizers must have felt they could finally rest and roll credits.

After all, they had given a lavish glow up to the 1939 Streamline Moderne May Company Building on the corner of Fairfax and Wilshire next to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum. And they had filled it with seemingly everything a film buff could want: E.T.! Rosebud! Cher’s Oscars dress! A roomful of TVs played Almodóvar clips, like some kind of outré Spanish Best Buy. There was also a wonderful collection of memorabilia from the great Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki. The only thing lacking, if you didn’t count a plaster life mask of Mel Brooks in a section on special effects makeup, were the Jews. Of course, famous Jewish names like Streisand and Geffen were etched in the museum’s industrial concrete, but this was a museum devoted to stories, and the Jewish stories had largely gone missing. Not only were directors, writers, and talent neglected, one did not learn about the Jewish moguls, those former vaudevillians and fur traders like Samuel Goldwyn, Jack Warner, and Harry Cohn, who’d transformed Los Angeles from orange groves and oil rigs into the movie capital of the world and created the art form and industry the museum had ostensibly been built to celebrate.

An outcry followed. The museum protested it would do something, or it had been planning to do something all along, or it would plan to do something—whatever, something would be done. It would be like one of those movies in which, following setback after setback, the right thing dramatically gets done in the end and we are all moved. Instead, it turned into one of those movies in which a large cumbersome thing is set aflame and everyone runs screaming.

Like so much in Hollywood, the museum’s development was long and winding. Its genesis lay in a realization by Ted Sarandos, the Netflix boss (and so, destroyer or savior of Hollywood, depending on whom you’re talking to), that the greatest engine of culture of the last century had no museum to call its own. Sure, Los Angeles had its cinematheques and screening series, and, in a sense, thanks to our phones, the entire world was now Hollywood. But how would the youth come to understand the power of film history? And, more importantly, where could Hollywood fete itself outside of awards season, which only lasts eight or so months a year?

The answer was that the academy would build itself a Death Star. But then came various social upheavals and internal dramas (not to mention the delays caused by the discovery of twenty-thousand-year-old fossils of sabertooth tigers, dire wolves, and ground sloths beneath the foundation of the future David Geffen theatre), and the museum felt it couldn’t just celebrate movies anymore. It had to feel a little bit bad about them too. The museum’s mission statement, displayed in the foyer, has the feeling of something heavily reworked by multiple task forces:

The Academy Museum advances the understanding, celebration, and preservation of cinema. . . . While there is much to celebrate about the power of cinema, there is also a long history of excluding diverse voices from the development of this art form. This has enabled and perpetuated damaging stereotypes based on race, ethnicity, nationality, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, and abilities. These stereotypes were wrong in the past and are wrong now. The Academy Museum pledges to address the history of cinema in truthful and inclusive ways. We hope you will join us as we work to build empathy, accountability, and a more equitable future through the lens of cinema.

You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll acknowledge the wrongness of stereotyping and oppression.

So, some objects that you may remember fondly from movies are displayed but are “contextualized”—a painted backdrop re-creating the Mount Rushmore on which Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint were pursued by James Mason’s goons in North by Northwest also notes that Lakota Sioux believe Mount Rushmore to be a desecration. See a screening in the plush Geffen Theater, and you will hear a solemn intonation that you are on Tongva land, after which you are free to enjoy your screening of Ralph Breaks the Internet. And in the current, wonderful exhibit on The Godfather, the taxidermic horse’s head from the film comes with a reassurance that real horses’ heads aren’t used for movies anymore. Still, not everything gets the contextual treatment. There’s a touristy Oscars Experience, where you hold your own statuette but are not personally held up for reappraisal or cancellation.

In what I think of as the Big Al’s House of Stuff part of the museum, Iron Man’s fist curls menacingly at a gremlin, but this aggression goes unchecked. C-3PO stands at the ready, without any warning of the dangers of British bots or AI. After three visits, I’m still not sure if the Academy’s multipronged mission can be a success. Can you reliably enjoy your popcorn and also choke on it a little bit too? What if you built a Death Star but aimed its superlaser cannons at yourself?

In truth, there had been something about the Jewish studio chiefs even when the museum opened. A small plaque, in the room devoted to teary Oscar acceptance speeches and winners’ getups, sat beside a photo taken at the Ambassador Hotel in 1927 of the tuxedoed men who, in building an empire of their own (as the title of Neal Gabler’s excellent account has it), created the Academy. But the caption was withering. It described the photo’s demographics as “white, overwhelmingly male,” which “clearly indicated who held industry power.” The maleness was true enough, though there were three women in the picture (Mary Pickford and two screenwriters), but I found the description of the beaming moguls as “white” profoundly irritating. The moguls may have looked that way to the twenty-first-century caption writer, but they didn’t to the WASP elites who barred them from country clubs, finance, and law and put quotas on their admission to leading universities. It was this pervasive discrimination that, in part, compelled them to create the motion picture industry in the first place—and perhaps also inspired them to assign their little prize-giving club a defiant and almost comically august name: The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

On my most recent visit to the Academy Museum, in mid-July, much had changed. Cher’s dress had been replaced by Coppola’s green tux from the night The Godfather cleaned up at the Oscars. That Ambassador Hotel photo was still there with the same caption. But now, on the third floor, sat the fruit of the museum’s resolve to do something about its Jewish problem: Hollywoodland: Jewish Founders and the Making of a Movie Capital, partly inspired by Gabler’s book.

When the exhibit launched in May, its curator, Dara Jaffe, exulted that it was even better than it would have been had it been part of the museum’s opening. Anticipation was high. But then some attendees read the wall text and noted the use of words like “predator,” “tyrant,” “frugal,” “womanizer,” and “oppressive” in describing the Jewish moguls. It was, an open letter noted, “the only section of the museum that vilifies those it purports to celebrate.” They had a point. I had been to the museum last year to see Regeneration: Black Cinema, 1898–1971, which was sensational, but I could not recall learning a single thing about anyone’s vices or proclivities. The focus, rightly, was on the Black artists’ achievements in a hostile world, not the kinds of things WASPs would call them at country clubs.

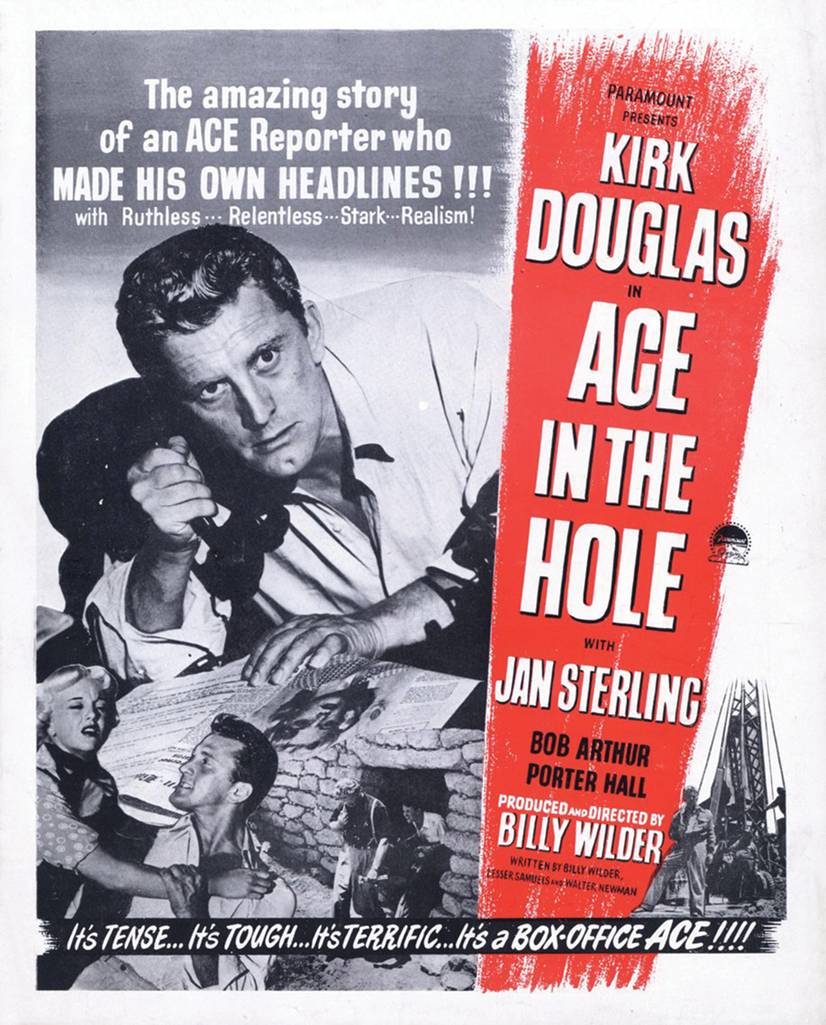

More apologies were issued. More task forces were formed. Offending words were deleted. By the time I went to see Hollywoodland, some tweaks had been made. The wall texts were more neutral in tone, with some interesting but general quotations from the Jewish humorist and screenwriter Leo Rosten and the great director-writer Billy Wilder. There were minutiae on the mergers that resulted in the major studios as we know them, which were about as exciting as detailed business histories tend to be. There was also a topographical display that lit up to show how the studios transformed Los Angeles. It had its charms, but it also felt like it belonged in a different museum.

The Hollywoodland room itself was small, but, to be fair, anyone looking for a perfect ratio of importance to size at the museum would be bound for disappointment: the cult filmmaker John Waters got a whole lavish floor; all documentaries ever made about social justice issues collectively received a cramped exit chamber on the way out of Stories of Cinema. However, Hollywoodland felt small in another way: The best exhibits at the museum have a lot of cool movie stuff, but there were few mementos from the moguls. I wasn’t hoping for an installation of old cigar butts, but it would have been nice to see something that evoked what Thomas Schatz has called “the genius of the system” that made stars and dazzled the world, rather than morose evidence of a “system of oppressive control” (as deleted wall text had it). And there should have been some artifacts to show. After all, 365 films were released by the studios in America in 1939 alone, including The Wizard of Oz (Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer’s MGM), The Adventures of Robin Hood (directed by Michael Curtiz for Warner Bros.), and Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (MGM again).

The exhibit’s final component is a short film, From the Shtetl to the Studio. The sinking feeling it provoked outdid anything I’ve ever seen at the La Brea Tar Pits. The short is narrated by Ben Mankiewicz of Turner Classic Movies. Mankiewicz’s grandfather Herman cowrote Citizen Kane, suggesting it’s possible to make a compelling movie about complicated moguls, but this gift seems not to be hereditary. The “Jewish founders”—a phrase repeated so incessantly, it feels like an incantation to make the angry letters from Jewish organizations stop—the short film chides, were “not conventionally religious.” (I could not recall the Pedro Almodóvar exhibit faulting him for his inadequate tithing to the church.) Escaping European persecution and domestic antisemitism, the moguls desperately wanted to assimilate as Americans and so anxiously avoided Jewish topics.

Yet the film’s audio track seemed to be produced by a different task force than its visuals. The narration scolds the moguls for wanting to obliterate their Jewishness, but they are shown proudly schmoozing with Einstein, wishing each other mazel tov, and presenting Oscars to one another in clips that could have been taken from shul dinners. (The Warner brothers, by the way, built a shul on the lot for their father, and their studio artist designed the windows at Wilshire Boulevard Temple; Carl Laemmle, the founder of Universal Pictures, helped with the Havdalah spice-holder–inspired chandelier.)

Studio heads, we learn, committed other sins. They marginalized LGBTQ characters, the narration says—though a glorious clip from Wings (1927) clearly shows two women being affectionate at a nightclub. Jews were subject to restrictions on where they could live, even in Los Angeles, we are told, but the moguls were too timid to address such discrimination—then it plays a clip from Auntie Mame (1958) addressing it. Studio films were marred by ableism—illustrated with a clip from Lon Chaney’s landmark The Phantom of the Opera (1925). At which point, I admit: I laughed, I cried.

It seemed churlish, in the Academy Museum of all places, to ignore or misconstrue the Jewish moguls’ achievement, their desire to create a genuinely popular, democratic art form that gave Americans a common culture, an art form that was suffused, sometimes subtly and sometimes overtly, with Jewish sensibilities and themes, from The Jazz Singer to the Marx Brothers and Danny Kaye (not to speak of Bugs Bunny) to two versions of The Ten Commandments. Not to mention the sophisticated work of émigré writer-directors such as Ernst Lubitsch, Fritz Lang, and Billy Wilder.

The documentary ends with the kind of montage that, when played during the Oscars, signifies bathroom time. According to the narration, the ultimate fulfillment of Hollywoodland’s promise was the world of diverse cinema we know today—there are clips from Moonlight, Carol, Roma, and then whatever the montage machine could cough up (The Tree of Life, Superman—I wondered who put a horse’s head in whose bed to get included?). Harry Cohn once said, “I may be a tough son-of-a-bitch but I built Columbia.” It turns out his goal all along was not to make a fortune entertaining millions but to one day see the release of a stylized drama, beautifully shot, about marginalized people in the 1950s to show on a handful of art house screens in America (one based on a novel by noted antisemite Patricia Highsmith, if we are going to be scrupulous about contextualization).

The final montage left me not only confused but saddened. “The Jewish Founders” were shamed and then erased, to use buzzwords that actually feel apt here. They built Hollywoodland so that one day they could be superseded and the real Jews, the chosen voices of diversity, could speak. The tradition of Hollywood self-importance they inaugurated was being used against them. Context was used not to help understand the world the moguls inhabited or the real constraints under which they operated but to bludgeon them into deserved oblivion—and not even with the Robin Williams plaster cast from Mrs. Doubtfire (second floor, extremely moving, I found).

Hollywoodland ultimately fails because it ignores a true and gripping story in favor of a clumsily imposed and altogether more forced one. It somehow manages to dramatize the memorable malapropism of Samuel Goldwyn—“include me out.” What makes this all the more perplexing is that, downstairs, the exhibit on Casablanca covers a lot of the bases that Hollywoodland might have (the exhibits even have a curator in common). The wall texts are rich in feeling, describing the predicament of its Jewish cast, including Peter Lorre and S. Z. Sakall, and crew, led by director Michael Curtiz and writers Julius and Philip Epstein. When they shot Casablanca on a Burbank set in 1942, the feeling of fear and political resolve of the filmmakers was quite real. A visitor might wonder if the Warner brothers who received adulation here were any relation to the Warner brothers being pilloried upstairs.

“I believe in America” are the famous opening words of The Godfather, and this could have been the moguls’ credo too. The Godfather was not universally beloved by Italian Americans upon its release, and one understands why (less so the mafiosi who hated it, given that it turned them into icons). But it was a work of art and has come to stand for a great deal in our culture. The exhibit devoted to it, unlike Hollywoodland, is a nuanced look at the struggles of immigrants and the tensions they must negotiate between realities, past and present. Walking through it, I thought of my grandmother, who survived the Holocaust and learned English from the Hollywood movies she saw in Australia. These movies, including the junkiest B features, created a popular shared culture barely imaginable today.

What might a better, less tendentious exhibit about Hollywood’s Jews have done? In the first place, it would have trusted their movies, which could be smart, savvy, subversive. It might also have located the real pathos and achievement at the heart of their story. And it might have traced the artistic legacy of the moguls, in real (not generic) fashion: Spike Lee, for example, has acknowledged his profound debt to Billy Wilder, a Jewish refugee who would not have written and directed his gimlet-eyed, witty films in America without the “Jewish founders.” (The Spike Lee exhibit last year, incidentally, had nothing to say about his ambivalent and controversial depictions of Jews and Italian Americans.) The clip from The Phantom of the Opera, which the curators lambasted for ableism, has inspired filmmakers like the Mexican Gothic master Guillermo Del Toro, who was moved by its “power and rage and despair.” Another installation at the museum shows how visual motifs echo across decades—Vertigo’s James Stewart, Alice in Wonderland, and Spider-Man all falling into the abyss, for example. A curator who wanted to explore distinctive Jewish themes and motifs could have traced them across the history of film in somewhat similar fashion. There is so much to say about Jews and Hollywood, and somehow this exhibit barely says any of it. It’s too busy fawning and scolding.

In a time of heightened antisemitism from the right and the left, if the Academy Museum is considering the sensitivities of everyone, could it not consider the accomplishments and sensitivities of Jews too? If you overcontextualize us, do we not bleed?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Intrigues and Tzuris

Have you seen the one about the Hasidic jewelers and the Albanian goons?

ArtScroll’s Empire

How did a Brooklyn-based, Orthodox publishing house corner the market on religious texts in America?

The Mocker and the Makhers

Herman Mankiewicz's life wasn't all drunken bets and witty repartee. After all, he wrote Citizen Kane. Life in 1930s "Eretz Demille."

Hollywood and Jerusalem

It would be marvelous to tell you that right after the meeting I strode indignantly to my forest-green Porsche, wheeled onto the Santa Monica Freeway, sped eastward on I-10 past Palm Springs, and didn’t stop till I got to Jerusalem. But that would be untrue.

Cary Rosenzweig

For further reading on Hollywood moguls secretly defending America against domestic Nazis in Los Angeles in the 1930s, see my wife's, Laura Rosenzweig, article here in JRB: "Hollywood's Anti-Nazi Spies," Winter 2014. Also, her book, "Hollywood's Spies: The Undercover Surveillance of Nazis in Los Angeles," published by NYU Press (2017) is available on Amazon. It was a Finalist in the National Jewish Book Awards.

Robert Berman

Great article! Just one minor correction. "Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer’s MGM." Although Goldwyn's name is part of the MGM logo, he had very little to do with the creation of the studio. He was connected with it many years before. In fact, he had his own studio: The Samuel Goldwyn Company.