The Mocker and the Makhers

Novelists, poets, and essayists share a common virtue: they don’t answer to anyone. Not so, screenwriters. Besides taking orders, they seem to invite derision, attract put-downs. “Glorified secretaries,” one studio makher called them. “Schmucks with Underwoods,” said another. In early Hollywood, they were replaceable, if well-paid, cogs, who often wound up turning on each other. If someone was insulting a screenwriter, it was often a fellow screenwriter.

The most memorable insult might be Ben Hecht’s 1926 invitation to Paramount. “Millions are to be grabbed out here,” it promised, “and your only competition is idiots.” The author of that famous telegram was Herman Mankiewicz. His invitations to “Eretz DeMille”—the land of Jewish-owned studios—hooked serious authors and playwrights. He was of their kind: success, for Mankiewicz, meant Broadway, not half credit on some blockbuster.

And yet, that’s exactly what he got. When he finished Citizen Kane, his tragic portrait of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst, he thought it his finest writing. Then he saw the rushes: it was still impressive, but it wasn’t his. The upstart Orson Welles, his audacious 25-year-old collaborator, had utterly reimagined it. There followed a lengthy battle over screenwriting credit that ended with a shared Academy Award and one winner telling the other, “Kiss my half.”

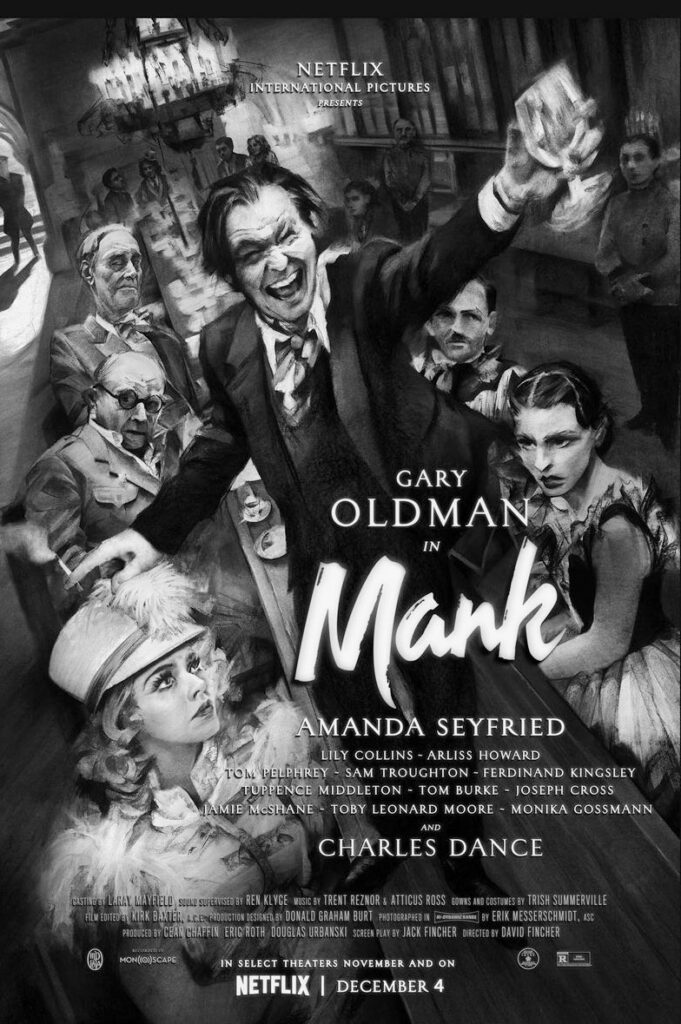

The debate over Citizen Kane—perhaps the most famous instance of disputed authorship in film history—is taken up in David Fincher’s new movie, Mank. Mank is really two movies: a charming, carefully crafted homage to 1930s Hollywood and a portrait of Herman Mankiewicz, whose magic touch went into The Wizard of Oz, Dinner at Eight, and several gut-busting Marx Brothers capers. Here, he’s granted posthumous revenge on Orson Welles but also a vivid, sardonic life of his own.

In real life, Mank was a fast and facile writer, having sharpened his pen as a theater critic and reporter. Born in 1897, raised in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, he was something of a child prodigy, graduating high school at the absurd age of 14 before entering Columbia University. There, he was a formidable drinker (“Mank the Tank” to his friends) and a fast, aggressive debater, a skill he learned at home. In all things, he veered toward excess: he smoked constantly, swore profusely, and flashed “the celebrated Mankiewicz leer” (as a friend put it) in every direction.

At Columbia, he learned two lasting lessons: people loathe boredom, and charm gets you everywhere. Never a Lothario—he was pale, stocky, plain looking—he became a dazzling talker, “the Central Park West Voltaire,” per Ben Hecht. But the silver tongue came with a seething temper, a frightening truculence. “Your personality is such that you cannot be fitted into an organization. You are too disturbing,” Harold Ross, the New Yorker editor, once told Mank, by way of firing him. Incensed, Mank protested. Ross reminded Mank that he once walked into Ross’s office, threatened to punch him in the face, and walked out.

For Mank, everything was material, and not just for his future plays. In the 1930s, Mank haunted Hearst’s lavish estate, gathering intel for future scripts (he would pour it all into Citizen Kane in 1940). He was also peddling a book, Twenty Years Among the Gentiles, chronicling his pith-helmeted adventures in Christian America. And he was drinking. Guzzling his way through endless parties until he either passed out or was thrown out, Mank was “as pathetic as a stray dog looking for a bone—luck,” his friend Hecht observed. His marriage to Sara Aaronson—“Poor Sara,” he nicknamed her—provided much of the love and stability in his life. But he was circling the drain, Hecht said:

He gibbers away from year to year, trying to formulate some sort of character out of his defects, incompetencies, and run-dry talents—and seeing through himself with such a mad, almost exuberant clarity as to render himself hors du combat in his own eyes before he can even get to his feet.

Finally, there was his gambling, which allowed his bosses to recoup much of the salary they paid him. “They can’t fire me,” Mank reassured his wife. “I owe them too much money.”

At a low point, seeking redemption, he began Citizen Kane, which is where Mank takes up his story. In the opening scene, Mank, played with wry gusto by Gary Oldman, is being squired to a secluded California ranch, where he’ll dash off Citizen Kane. When he enters, he gets awful news—“dry house”—which ruins any chance of fun. “I’m toiling with you in spirit,” Welles says over the phone. “Trapped,” Mank sighs.

Indeed he is, but Mank feels loose, skipping around in time. First, we flash backward. It’s the early days of sound; Hollywood is becoming the West Coast chapter of the Algonquin Round Table. In real life, Mank was delighted to arrive. “At the moment, Hollywood really seems to be Paradise,” he told a friend in 1926 after entering sun-drenched, citrus-filled Arcadia. Fincher portrays this period wonderfully, with a jaunty soundtrack and kinetic tracking shots. Mank was young; so was Hollywood. Money and excitement were everywhere.

The pleasures of Hollywood mischief are evoked joyfully, playfully. In a pitch meeting, Mank, Ben Hecht, and Charlie Kaufman foist a ridiculous plot on David Selznick. Here, Hollywood divides into those who take the movies seriously (the producers) and those who know it’s all a game (the writers). There’s no question who’s in control. At one point, Mank recognizes MGM head Louis B. Mayer, cracks a friendly joke, and walks off. “Who was that again?” Mayer asks a director. “Just a writer,” comes the reply.

Being ignored and rebuffed had an upside: it fostered camaraderie among writers and inspired one thousand blistering jokes about studio heads. This class warfare—the mockers vs. the makhers—provides Fincher’s best material. Like the early screwball comedies, Mank is drunk on wordplay and repartee. “You don’t much like Mayer,” Mank’s secretary says, smiling, and Mank can’t resist the setup. “If I ever go to the electric chair, I’d like him to be sitting in my lap.” Earlier, Mayer calls MGM “Mayer’s Ganza Mishpucha,” likening his employees to family members, then slashes the family’s salaries. “Not even the most disgraceful thing I’ve ever seen,” Mank says, smirking.

The quips come fast and furious in Mank—the party almost never stops. “What’s German for ‘blabbermouth’?” Mank asks, teasing his immigrant housekeeper after she confides in his new secretary. And that secretary, a young, courteous Brit, seems to turn Mank into Noël Coward. “Jesus, what is that?” he exclaims to the woman. “Sunlight,” she replies, raising the shades at midday when Mank wakes up. “Mother of God,” he says, recoiling. “Where did the night go?”

But cleverness has its limits, and Mank flirts with seriousness as it proceeds. The forlorn Mank—pasty, bloated, jowls permanently drooping—clings to his wit like a life preserver; his dignity lies in his cleverness, his savviness, his survivorship. Oldman plays him as a shambling, beleaguered has-been: on a good day, he’s rumpled and sweaty; on a bad day, he looks like someone just dunked him in a pool. “Long night?” Mayer asks Mank as he shuffles on set. You could say that, if a night can stretch from 1930 to 1940. Yet Mank’s air of beleaguerment doesn’t make him pathetic; he looks weary, not pitiful. Smiling, he notes life’s absurdities and futilities. He’s a man enjoying his misery.

For a while, at least—and then he isn’t anymore. He makes a buffoon of himself at one of Hearst’s famous bacchanals. He struggles to finish the screenplay. (“Dreck, it’s all dreck,” he mutters to himself. “None of it sings.”) This Mank, an adult-adolescent, is incapable of confronting anything unpleasant about himself. His constant joking is a barrier against feeling, a means of distraction, of keeping people at a distance. Slowly, his defenses crumble. “I’m washed up, Joe,” he tells his younger brother, whose star is rising as Mank’s is fading. “You made yourself court jester,” Joe agrees.

These scenes invest the film with unexpected gravitas. Mank even acquires moral stature, making a brief turn as the movie’s conscience. His foil is Mayer, the slick, arrogant, bullying MGM head. “Hitler, Shmitler,” he scoffs, dismissing Mank’s warnings about German fascism. In recent years, Mayer’s cooperation with German film censors has drawn scrutiny, and Mank joins the prosecution. “You don’t turn your back on a market as big as Germany,” Mayer lectures Mank—and we’re meant to bristle at the greedy, amoral big shot, who soon wonders, cluelessly, “What’s a concentration camp?”

How accurate is Mank? Fincher’s script (written by his late father, Jack, a reporter and screenwriter) is a treasury of gossip, famous quips, and Hollywood lore, much of it tweaked and scrambled. Quotes change mouths; events change dates. Mank may have vomited in actual dining rooms but never in William Randolph Hearst’s, as he does in Mank. “It’s all right,” he says, “the white wine came up with the fish.” In real life, he offered that line to producer Arthur Hornblow Jr.

Of course, all biopics dramatize and fictionalize; it’s silly to expect factuality. At the same time, Mank invites curiosity: it jeers and honors real people; it tumbles into historical arguments. If the Finchers’ film is compelling, it’s partly because it feels rooted in historical fact. (A subplot about propaganda in the 1934 gubernatorial election raises the moral stakes, as do the discussions of Hitler and fascism.)

Its mise-en-scène, that bustling 30s Hollywood, is beautifully rendered. It’s a Jewish Hollywood, familiar from Neal Gabler’s An Empire of Their Own. (Virtually all the writers and producers are Jewish. The two Charlies, Lederer and MacArthur, are the token goyim, straining to get a word in.) In a feat of casting, many of the actors resemble their real-life counterparts. Ben Hecht (Jeff Harms) is balding and slouchy; David O. Selznick (Toby Moore), dumpy and wirehaired; Ferdinand Kingsley looks remarkably like Irving Thalberg, whom he plays not as a doomed Hollywood genius but as Mank’s foil, a coldly calculating Machiavellian makher.

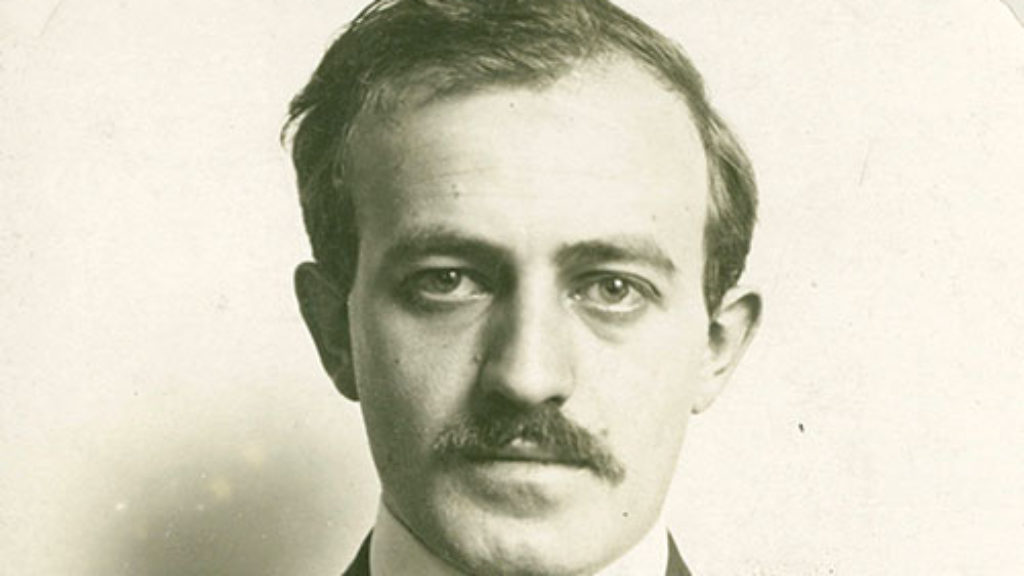

Oddly enough, it’s Gary Oldman, with his long, swishy hair and hangdog mien, who least resembles his character. Google “Herman J. Mankiewicz” and you’ll meet a natty, put-together gentleman with short-cropped hair, a spruce suit, and a wry half-smile, not the permanently rumpled schlub played by Goldman. As for “Poor Sara,” Mank’s heroically calm, forbearing wife, we get a simple, blandish portrait (Tuppence Middleton, not her fault). Here, she’s polite and prim, her energy siphoned into the full-time job of rescuing her husband. But the real Sara could be caustic and clever, a real spitfire. “She is IMMORAL. So help me,” wrote the wickedly observant Hecht. “She uses dirty words, drinks, embraces idiotic actors and acts like yesterday’s Madonna on a rampage.” As for the Herman-Sara union, Mank subtracts much of the tzuris and frustration. We see the saintly Sara (“Go to sleep, meshuggene,” she says sweetly, tucking in her drunk husband), not the angry, frustrated Sara who sometimes threatened divorce and several times left her husband. (In her most prickly film moment, she insists that Mank cease the “Poor Sara” business.)

But it’s Mank himself who seems reduced—simplified—on screen, despite Oldman’s expansive performance. In part, that’s because we never learn what shaped him, what damaged him. Without more backstory, we can only guess. In high school, he styled himself a debunker, a Jewish Mencken. After college, he joined the famous Algonquin group, adding a layer of urbane sophistication to his persona. (A sincere copycat, he borrowed George Kaufman’s mannerisms and Alexander Woollcott’s dandyish wardrobe.) All along, he kept up the performance of Herman Mankiewicz. He often seemed unsure of who he was.

Much of his insecurity—he seemed plagued by the need to be the wittiest guy at every party and a fear of seeming sincere or heartfelt—can be traced back to his childhood. The most powerful figure in Mank’s life, his father, Franz, was a stern, demanding man who provoked his wife to book-hurling rages (a similar scene, inspired by Orson Welles, pops up in Citizen Kane and is repeated in Mank). The Finchers largely eschew psychology, but it’s plausible that this harsh, unpleasable father produced a brittle, resentful, emotionally needy son, whose thirst for affection could never be satisfied.

By the late 20s, Mankiewicz was thriving professionally but sinking socially, his boorish, drunken behavior doing him in. He had acquired a nickname, “One-Time Herman”—as in, you’ll invite him once to a party but never again. Actors avoided him. “Directors . . . rush screaming from the set,” one writer recalled. In Fincher’s film, Mank needles his higher-ups. In real life, he scattered buckshot everywhere: at bosses, at friends, at party hosts. Beneath his surface charm was a “lurking violence,” one biographer noted. That seething aggression is absent from Oldman’s portrayal; his Mank is bumptious and hostile but never frightening, as the real Mank could be (“I was scared of him and stayed out of his way,” the editor Katherine White recalled).

Mank is a portrait of artistic failure—the great theme of Mank’s life, and also its central riddle. What thwarted him? Why, despite obvious talent, learning, and ambition, couldn’t he create art? Mank suggests several answers, from his gambling (which consigned him to hackwork) to his drinking (which cut down on lucid writing hours) to his love of socializing (which kept him tethered to Hollywood) to his lack of sitzfleisch (the family quota belonged to Joe, a model of discipline).

All factors, surely. But Mank’s real Achilles’ heel was less obvious. Something was missing. What artists possess—curiosity, human sympathy, self-knowledge, negative capability, the ability to face unpleasant truths, a tether to one’s unconscious mind—weren’t usually in his repertoire. Early on, Hecht smelled “the doom of unproductivity” on his friend, but the problem wasn’t that he squandered his talent writing movies. Rather, he was unlucky in his ambitions—good at the thing he disdained (movies) and bad at the thing he admired (plays).

Yet he somehow managed to write Citizen Kane, a great cinematic work of art by any measure. With confidence, the Finchers elevate Mankiewicz over Orson Welles as the film’s preeminent genius. This argument is hardly settled, yet one can reasonably say that both men’s contributions were indispensable, if perhaps unequal. Without Welles’s bold, visionary editing, Mank’s bloated script was unfilmable. No Welles, no Citizen Kane. Then again, editing is easier than writing; only the writer creates something out of nothing. And that “something” could only have come from Mankiewicz. Citizen Kane taps a deep vein of disappointment, regret, and loss—a middle-aged perspective, not a 25-year-old’s.

According to credible estimates, Mank wrote 60 percent of Citizen Kane, although Mank suggests a far higher percentage, echoing Pauline Kael’s famous (and controversial) New Yorker essay, “Raising Kane.” Kael would certainly approve of Fincher’s boosterism. Here we have Mank writing everything, while Welles, a vain, insolent credit hog, throws his massive tantrum, demanding exclusive credit. In real life, Mank was outraged, threatening a scorched-earth campaign if the “juvenile delinquent credit stealer” didn’t acknowledge his contribution. He dispatched Ben Hecht to write a polemical essay setting the record straight. At parties, he buttonholed strangers: How did you like my film, Citizen Kane, he would ask.

Finally, with characteristic audacity, Fincher tackles Mankiewicz’s politics. The real Mank, the film suggests, was the committed antifascist who wrote the anti-Hitler screenplay The Mad Dog of Europe in 1933. Though the film was never produced, it was so threatening to Nazi officials that Joseph Goebbels banned Mank’s films from Germany. Thwarted, Mank accepted the film’s demise and went back to writing comedies. Meanwhile, he quietly sponsored German-Jewish refugees, helping them resettle in the US.

All true; however, the actual Mank was a more complex, difficult character. Publicly, Mank praised isolationists (“I am an ultra-Lindbergh,” he declared) and opposed America’s entry into World War II. “If this should happen, I believe that the worst will have happened for America,” he said, fretting to Irving Berlin. When the war began, he opposed US aid to Britain. It was folly to fight the Germans, he said. “Would you go into the ring with Joe Louis?”

This isn’t Fincher’s Mankiewicz, a mostly menschy, good-hearted fellow. In truth, Mank was harder to parse. His politics were a mishmash—pro-union, anti-Communist, anti–big government, elitist. Did he actually believe everything he said? Reviewing his strange, surprising statements, it’s hard to know what reflected a whim, a conviction, or a desire to shock and offend. Perhaps his strongest pull was toward contrarianism. “Pick a subject for debate, and I’ll take the other side,” Mank told Hecht, and their arguments would take off. Stories about Mank recall the old Groucho Marx line: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.”

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, he reversed himself again, quickly enlisting, or attempting to—no one with Mank’s medical history could possibly have served. He was rejected immediately. “Bad kidneys,” his biographer noted.

In short, the real Mank was more offensive, abrasive, and prone to what his brother called “binges of perversity and extremism” than the movie suggests. Indeed, there were two Herman Mankiewiczes—a great performer, hugely charming, and a bitter hothead, given to antagonizing friends and bosses, testing their loyalty and devotion. In Mank, we see plenty of Good Mank and somewhat less of Difficult, Truculent Mank. What we rarely see—except, perhaps, between the lines—is his inner turmoil, his hidden pain and frustration. “I seem to become more and more a rat in a trap of my own construction,” Mank wrote from Hollywood in 1942. Toward the end of life, he recognized his own tragic arc. “I don’t know how it is that you start working at something you don’t like, and before you know it, you’re an old man.” There’s nothing in Mank that matches the poignancy of those two reflections.

Mank seems to realize its limitations. “You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours,” Mank declares toward the end. “All you can hope is to leave the impression of one.” Like its hero, Mank makes a charming impression without ever acquiring the weightiness of true art. At its best, it’s wonderful company, a witty, generous, beautifully crafted homage to a forgotten screenwriter who deserves a second glance: movieland’s greatest conversationalist, its finest raconteur, whose one great success was an indelible classic.

Suggested Reading

History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

On-screen, Mel Brooks was hysterically funny. Off-screen, he could quickly shift to morose or mean.

Some Kind of Genius

Ben Hecht’s life should come with a warning label: Biographer, beware. A trickster, a prankster, a cool Wildean ironist, he was always a fast-moving target.

Hollywood and the Nazis

In their dealings with Germany in the 1930s, were Hollywood’s moguls just watching the bottom line or aiding the Third Reich’s PR machine?

Remembering the Forgotten

Historian Bernard Wasserstein narrates Jewish life in Europe between the world wars.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In