A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

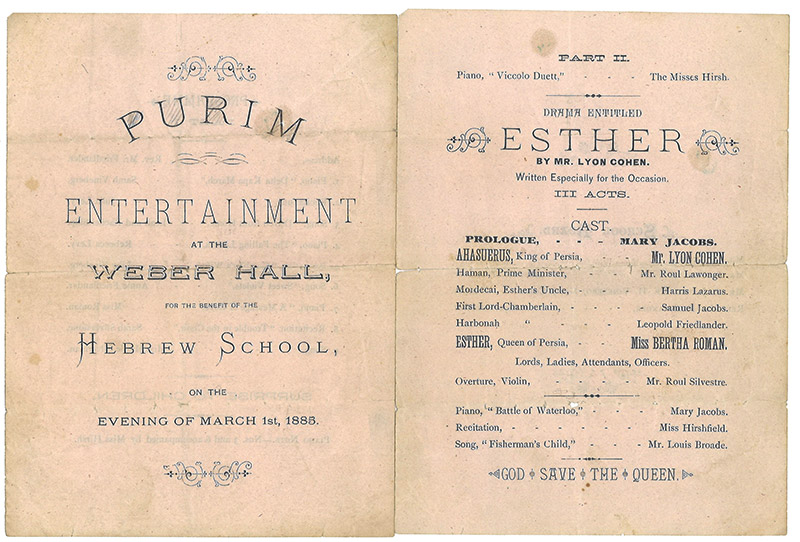

On the eve of Purim, March 1st, 1885, seven hundred people crowded into Weber Hall on St. James Street in Montreal to watch the students of the English, German & Polish Congregation put on a Purim spiel. In addition to a play called “Esther,” there were songs, poetry recitations, and instrumental performances. The play was written by a sixteen-year-old named Lyon Cohen, who also starred as Ahasuerus. Cohen would grow up to be not only a leading figure in the synagogue (which was later renamed Congregation Shaar Hashomayim), but one of the foremost leaders of Canadian Jewry. In fact, his play, which was praised at the time in the Montreal Herald, was later re-staged twice in his honor, once in 1919, and a second time in 1935.

Lyon Cohen was also the grandfather of poet-singer Leonard Cohen, whose relationship to the synagogue would turn out to be more ambivalent. “Lenny,” as he was then known, was raised as a child of the congregation. In his semi-autobiographical 1963 novel The Favourite Game, Cohen wrote:

In those dark ages, early adolescence, he was almost a head shorter than most of his friends … But it was his friends who were humiliated when he had to stand on a stool to see over the pulpit when he sang his bar mitzvah. It didn’t matter to him how he faced the congregation: his great-grandfather had built the synagogue.

Traces of Cohen’s childhood flow through the synagogue’s archives. In 1950, he was a participant in the Leadership Training Fellowship, run by the Jewish Theological Seminary to prepare promising Jewish teenagers for careers in Jewish community service. Though he somewhat characteristically failed to submit his final report to the synagogue’s rabbi, another student’s account of the conference described Lenny dramatically exiting the Seminary at the end of the event with the declaration, “I am full of religion!”

That same year, back in Montreal, he took part at the synagogue in a playful mock-trial of “Jewish youth” for the “serious charge of being neglectful of its responsibilities, and indifferent to its opportunities for spiritual and cultural growth as part of the Jewish community.” Cohen took the role of defendant, successfully acquitting himself and his peers from the charge of indifference.

Fourteen years later, as a young poet, Cohen was still angry, perhaps even estranged from the community, but not indifferent. As Matti Friedman writes in his forthcoming book Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai, “in 1964 . . . Cohen enraged listeners in Montreal with a speech dismissing the tidy edifice of the Jewish community’s life as a hollow perversion of their divine mission.”

However, Cohen’s life in and out of Congregation Shaar Hashomayim was not just one long rebellion. Recently, while working in the synagogue archives, I discovered a photograph of the young cast of the 1947 Purim spiel, and standing there in the front row, smiling broadly, is a not-yet-bar-mitzvahed Lenny Cohen. He is wearing a waiter’s costume and grinning under a greasepaint mustache.

In his great song “Bird on the Wire,” Cohen sang “Like a bird on a wire/Like a drunk in an old midnight choir/I have tried in my way to be free,” and one catches glimmers of some of the ways he tried to free himself from his grandfather’s legacy in the archives of Congregation Shaar HaShomayim. And yet, in his celebrated album You Want it Darker, released when he was 82, it was to his childhood shul’s choir and its cantor, Gideon Zelermeyer, that Cohen turned for those haunting backing vocals of the title song.

That song is famously somber, and yet now as I think of Leonard Cohen, his childhood shul and his complex relationship to Jewish tradition, I also see the bright, infectious smile of that twelve-year old waiter in the 1947 Purim spiel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Darkness and Light: Leonard Cohen and the New Cantors—A Playlist for the High Holidays

Old World Ashkenazi cantorial art—khazones—is making a comeback, with a surprising little boost from Leonard Cohen's new single (yes, that Leonard Cohen).

A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

Despite all of Bob Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he really was a child of the American heartland. Winning the Nobel Prize might actually be his most Jewish achievement.

18 Questions with Jeremy Dauber: The Purim Edition

Who ruled the Borscht Belt: Allan Sherman or Lenny Bruce? Jewish comedy expert Jeremy Dauber casts his vote in a humorous interview—just in time for Purim.

Hidden Faces and Dark Corners: Megillat Esther and Measure for Measure

What happens when the hidden is revealed? Reading Megillat Esther alongside one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays” shows that question to be at the heart of Purim’s paradox.

Shoshana Socher

Wow. Who knew? Cue "Hallelujah"

Allan Nadler

What a sweet and wonderful piece, perfectly timed.

Personally gratifying and nostalgic as I'll be at Leonard's (and my) shul, Shaar Hashomayim in 90 minutes for megilla-leynen, but no moustache and not in a waiter's uniform.

Thank you, JRB, for this !

Len Moskowitz

Leonard Cohen as a Buddhist monk, before a statue of the Buddha:

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/738801513867265144/