Hidden Faces and Dark Corners: Megillat Esther and Measure for Measure

What happens when the hidden is revealed? Does seeing mean believing? Or does removing the veil of mystery only prompt us to turn away? Reading Megillat Esther alongside one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays” shows that question to be at the heart of Purim’s paradox.

The traditional interpretation of Megillat Esther plays a game of hide-and-seek at the highest level. On its face, the story is a piece of court intrigue right out of The Thousand and One Nights. If the great classicist Elias Bickerman was correct, it likely began as two tales of non-Jewish origin—one about a conflict between the vizier and the queen, the other between the vizier and a courtier—that were adapted and combined by a Jewish author to tell a story about exile, about being at once powerful and vulnerable.

Were it not canonical, we might read Esther as a comic story of pluck and luck. Ahasuerus, far from being a pharaonic terror, is unable to command even his own wife, and the law of his kingdom is simply that everyone should drink their fill and take their pleasure—the opposite of what we normally mean by law. The villainous vizier, Haman, is a shallow and vain figure, who, in possibly the best example of overkill in world literature, plots genocide in response to a personal slight from his rival Mordechai.

Haman’s hatred of Jews is apparently not widely shared; when the edict for destruction goes out, the people of Shushan are befuddled. And deliverance, when it comes, is not from heaven. The Jews see no sign of a strong hand and outstretched arm. Indeed, the book famously contains no mention of God, and the two Jews who save them are so assimilated that their names derive from Babylonian gods (Marduk and Ishtar). A series of coincidences place Esther in the palace and Mordechai in a position to find favor with the king. And after they have triumphed by means of their wits, the determination of the Jewish people to provide for their own defense is still essential, since the king’s decree cannot be recalled. Even the date of intended destruction is determined by chance. It is all too easy to read the book as taking place in a God-abandoned world where we are responsible for our own salvation.

But Esther is canonical. So tradition detects the hidden presence of God in a punning clue: A verse in Deuteronomy warns Israel that “I will keep my countenance hidden on that day” (Deut. 31:18), and the Hebrew for “surely hide” is haster astir, which sounds a little like “Esther.” On this understanding, God hides His face when it is time to punish His people through the actions of men like Nebuchadnezzar or Haman. And He saves with the same hidden hand that moves history through coincidences and apparent chance.

This is how Mordechai himself tells Esther (and us) to understand the story. Salvation will come one way or another, he tells her, and one should act as if one has a providential role to play even though there is no sign. Nonsigns thus become signs, and every profane or comedic element in the book is transformed into a greater source of wonder. A contemporary scholar, Moshe Simon, even suggests that the absence of God’s name from the Masoretic text—it appears in the Septuagint—is intended to draw more attention to what is absent and thereby make it more clearly present.

However familiar, this reading is still strange. A comparison with the Joseph story shows just how strange. While Joseph comes to understand the misfortunes of his life as providential (“Although you intended me harm, God intended it for good,” he says), he has led a life of destiny from his youth, marked by extraordinary dreams and signs. The narrative has prepared us from the first to see Joseph’s story as one marked by divine providence. Its aim is not to surprise us with ironic reversal but to deepen our understanding of the scope and purpose of God’s design.

No such preparation is provided in Esther. When Mordechai asks Esther to consider the possibility that she was placed in the palace for a purpose, he gestures at a plane of existence for which the reader has seen no evidence. Esther’s own faith, with which she girds herself to approach Ahasuerus, is stoic: “And if I am perish, I shall perish.” To read such a story providentially, as Mordechai and tradition bid us, requires us to see the book’s biblical status as itself evidence of God’s controlling hand, the very fact that we read the story in a synagogue on Purim implying that there is destiny in coincidence, fulfilled prophecy in surprise.

It’s a neat trick. But would it work if we could actually see the author manipulating those chance occurrences? Make him visible, make it possible to ask why this way and not that, and perhaps we would find him outrageous rather than benevolent.

I believe we would. How do I know? Because Shakespeare wrote that play. In Measure for Measure we see just that kind of manipulation by a character with godlike pretensions and with some of the same plot elements and turns as Esther.

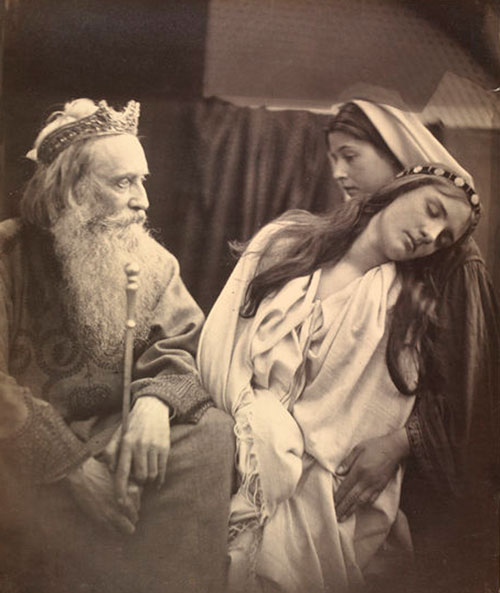

Measure for Measure is one of Shakespeare’s problem plays, a term invented by the 19th-century critic F. S. Boas to describe tonally ambiguous works that end with neither comic resolution nor tragic catharsis. It is a fit companion for Megillat Esther, and the situation of the play—in which an evil lieutenant is granted absolute power by an inattentive sovereign and threatens the life of a reluctant heroine’s kin—suggests other parallels as well.

I would love to claim that Shakespeare’s title came from Esther and could even cite a text—the Talmud explains Ahasuerus’s command to Vashti to dance nude at his feast: “For with the measure that man measures is he measured” (Megilla 12b). But Shakespeare’s knowledge of Talmud was limited to say the least, and in fact his play’s title comes from the Sermon on the Mount:

Judge not, and ye shall not be judged: condemn not, and ye shall not be condemned: forgive, and ye shall be forgiven. Give, and it shall be given unto you; good measure, pressed down, and shaken together, and running over, shall men give into your bosom. For with the same measure that ye mete, withal it shall be measured to you again. (Luke 6:37–38)

The action and message of the play foreground the Christian polemic against “Old Testament” conceptions of justice and in that sense contrast with Esther. Where Esther climaxes with Haman hanged on his own gallows and the Jews’ persecutors defeated by Jewish arms—measure for measure—Shakespeare’s play moves from justice as a matter of rules and consequences to an approach that seeks to turn justice into a measure that overflows its measure.

That is the journey that Isabella—Shakespeare’s protagonist and Esther’s parallel—takes over the course of the play. From a beginning where she is reluctant even to plead for her own brother’s life because she abhors his sin (fornication), she ends up pleading for the life of the corrupt man who, she believes, has killed her brother, because, as she says, “A due sincerity govern’d his deeds, / Till he did look on me.” This is a rejection of the kind of poetic justice with which Esther climaxes.

But the crucial parallel between the stories lies elsewhere. They both play hide-and-seek, but in Measure for Measure we see who wears the mask. While Isabella is the heroine, Shakespeare’s play has a second protagonist, who orchestrates the action and manipulates her: Duke Vincentio of Vienna.

The duke’s first act is to announce his intention to quit the kingdom and to resign his power to his trusted lieutenant, Angelo, a harsh moralist. Once safely away, the duke, now ensconced in a monastery, explains his reasons for abandoning Vienna to a friar:

We have strict statutes and most biting laws.

The needful bits and curbs to headstrong weeds,

Which for this nineteen years we have let slip;

Even like an o’ergrown lion in a cave,

That goes not out to prey. Now, as fond fathers,

Having bound up the threatening twigs of birch,

Only to stick it in their children’s sight

For terror, not to use, in time the rod

Becomes more mock’d than fear’d; so our decrees,

Dead to infliction, to themselves are dead;

And liberty plucks justice by the nose;

The baby beats the nurse, and quite athwart

Goes all decorum.

In short, things have gone to hell, and it’s strict Angelo’s job to put them right. The friar protests that the duke should have enforced the law himself, but the duke retorts that “’twas my fault to give the people scope, / ’Twould be my tyranny to strike and gall them.” Vienna has, like Ahasuerus’s empire, been under the rule of every man drinking his fill and pursuing his pleasure. Just as God retreats behind a veil when He chooses to chastise His people for their transgressions, so the duke has chosen to hide his face and place his power in the hands of Angelo, who can punish in his name without turning popular opinion against the duke himself.

But the duke does not, in fact, abandon Vienna. Instead, he immediately returns, disguised as Friar Lodowick, intending to observe Angelo and see whether he maintains his stern virtue once he has tasted power. At first he does, tearing down brothels and arresting Isabella’s brother Claudio for having gotten his fiancée pregnant before their wedding. Prompted by her brother’s roguish friend Lucio, Isabella pleads for his life, and Angelo finds himself, for the first time, stung by the arrows of desire, drawn specifically to her virtue as he has never been drawn to mere beauty. He promises to spare Claudio if she will surrender to his desire. When Claudio begs his sister to agree to Angelo’s demands and save his life, Isabella turns on him with coruscating venom.

It is at this moment that the duke intervenes—and the play changes, quite suddenly, from an incipient tragedy to a bizarre comedy. The duke does not reveal himself and right things, though he easily could. Instead, he enlists Isabella in a scheme to save her brother without her sacrificing anything, starting with a bed trick, swapping Isabella in the dark for another woman, Mariana, who had once been engaged to Angelo, but requiring ever more outrageous interventions to achieve his desired ending.

Why does the duke behave this way? The answer goes directly to Shakespeare’s intentions, because the disguised duke was Shakespeare’s major innovation to the preexisting plot. Shakespeare’s sources for Measure for Measure—George Whetstone’s Promos and Cassandra and an Italian story by Giraldi Cinthio that was Whetstone’s source in turn—gave him the tale of an unjust magistrate demanding a woman’s sexual favors to spare her brother’s life, along with the seedy underworld of whores and tapsters. But in those earlier stories, the just ruler departs at the outset, discovers his deputy’s unjust behavior upon his return, and then sets things right in a poetically just manner—measure for measure. Shakespeare’s duke remains and controls the remaining action of the play from behind a disguise. Why?

Unlike Shakespeare’s other “director” characters—Hamlet, Rosalind in As You Like It, Edgar in King Lear, or even the wonder-working Prospero—Vienna’s duke has no clearly human motives, however tangled. Moreover, he compounds our discomfort by doubling and trebling down on deception as the situation grows worse. When Angelo welches on his deal, and orders Claudio killed after all and his severed head delivered to him, the duke searches for an alternative sacrifice. His first choice is Barnardine, a convicted murderer who for years has been too continuously drunk to be executed. The convict, however, refuses to play along, declaring that he “will not die today for any man’s persuasion.” The line resonates powerfully through the play, for if justice is not force, then it depends on a community of agreement that includes even the convict. But what manner of man would seek to persuade this fellow to die not for justice but for the sake of his plot, when he might save Claudio’s life just by taking off his cowl?

He never does take off that cowl of his own volition. When he returns to Vienna as himself, the duke stages a scene at the gates of the city where Isabella—whom he has again misled, telling her Claudio is dead when he has in fact been hidden—accuses Angelo. In what is possibly the maddest scene in Shakespeare, the duke publicly rebukes Isabella, leaves the stage, returns in disguise as Friar Lodowick to accuse the duke of being unjust, and is about to be put to torture when the comic rogue Lucio finally pulls his cowl off, revealing his true identity. And even then he’s not through. The duke dispenses justice “measure for measure,” ordering Angelo to be married and then executed, prompting Isabella to make her final turn toward forgiveness. Only then does the duke reveal that her brother is alive.

Theatricality is an insufficient explanation for these mad antics, which, after all, distract the audience from the pathos of Isabella’s journey. Earlier in the play, Lucio described his sovereign to Friar Lodowick as the “fantastical duke of dark corners.” He meant to suggest that the duke was lax in enforcing moral laws because he had a taste for nightlife himself.

But Lucio’s description is apt in another way. This duke hides for sheer love of hiding, manipulates for the love of manipulation, and holds himself to be entitled to do these things because of his position and because he aims at his subjects’ greater good. Indeed, he says explicitly that he hides from Isabella knowledge of her brother’s life “To make her heavenly comforts of despair, / When it is least expected.”

That is the source of our discomfort—a conclusion that should not be comfortable for those who wish to see God’s face hiding in the dark corners of Vashti’s banishment and Mordechai’s eavesdropping.

The orthodox Christian interpretation of Measure for Measure has attempted to resolve the problem of the duke’s character through allegory. G. Wilson Knight, for example, argues that the duke is a figure of Christ, Vienna a type of hell, Act V a version of the Last Judgment, and the duke’s deceptions the means by which Angelo and Isabella are taught to embrace the gospel truth. Angelo himself seems to endorse such a reading, exclaiming when the duke is finally unmasked:

O my dread lord,

I should be guiltier than my guiltiness,

To think I can be undiscernible,

When I perceive your grace, like power divine,

Hath look’d upon my passes.

Turning the duke into an allegorical figure relieves the drama of its reality; it reveils what has been revealed. Alternatively, another line of interpretation suggests that the duke is playing at God. In that case, the numerous parallels with the Gospel narratives are ironic, limiting the scope of our discomfort with the duke by associating it with the magnitude of his pretensions.

But Shakespeare was ahead of his critics on both counts. Rather than emphasize either the distance or the similarity between the duke and his divine counterpart, Shakespeare encourages us to see double. After Barnardine has refused to die, when the duke despairs of bringing his plan off, Shakespeare invokes another manipulator of events, this one unseen:

PROVOST

Here in the prison, father,

There died this morning of a cruel fever

One Ragozine, a most notorious pirate,

A man of Claudio’s years; his beard and head

Just of his colour. What if we do omit

This reprobate till he were well inclined;

And satisfy the deputy with the visage

Of Ragozine, more like to Claudio?

DUKE VINCENTIO

O, ’tis an accident that heaven provides!

If Shakespeare were God, that would be precisely accurate. And in a potboiler, such a convenient coincidence would be expected. But we have been too aware of heaven’s absence so far to let it pass so easily.

Like Mordechai, Duke Vincentio points to a plane of existence for which we have seen no evidence to date. But in this case, the reason we have seen no such evidence is that someone else has been pulling the strings, onstage and very visibly. After all, the duke had suggested they lop off Barnardine’s head only moments before. In that context, the transparent device of the dead pirate who happens to look like Claudio associates the author of the play with the duke’s games of hide-and-seek, taints that author with the duke’s pretensions, and inevitably prompts us to analogize between the director we see on stage and the one hiding off stage—and, behind that, the one directing all.

Interestingly, allegorical interpretations of Esther have arisen for similar reasons but in the opposite direction. If Esther’s problem is that God is too hidden, allegorical interpretations suggest that He is not hidden at all. Rather, He was there all along—as Ahasuerus. At first glance, such an interpretation seems ludicrous. Ahasuerus is a fool, a drunkard, prone to anger and to forgetfulness. Midrash even magnifies his wickedness, to make him a fitter antagonist for the God who causes Mordechai to be elevated.

And yet, as the all-powerful ruler of a global empire, Ahasuerus readily accumulates attributes of the divine. His word is law and cannot be recalled once uttered. Like God at Sinai, he may not be approached without permission on pain of death. Midrashic commentary on Esther repeatedly suggests that references to the king—as, for example, when he is troubled in his sleep—have double meanings, referring not only to Ahasuerus but to God as well. From there, it is a short jump to mystical interpretations, according to which Esther is the human soul, Ahasuerus the divine presence, and Mordechai and Haman his protective and persecuting angels.

What are the satisfactions of such allegory? Perhaps that they obscure the trauma of near-death. If God was watching all along as our lives were hanging by a thread, then how different is He from a drunken, inattentive ruler? Perhaps we read until we are unable to distinguish God from Ahasuerus for the same reason that we drink until we cannot tell Mordechai from Haman.

Reading Megillat Esther by the light of Shakespeare’s play forces us to face our ambivalence about the character of this hidden manipulator, to feel both the weight of his sovereignty and our frustration at his lack of forthrightness. Shakespeare puts those feelings to their ultimate test at the end of his play, when—immediately after revealing that her brother lives—the duke proposes marriage to Isabella. Within an allegorical interpretation, this just completes Isabella’s spiritual trajectory; now that she has found Christlike forgiveness, she can become a bride of Christ. But Isabella never responds to the duke’s proposal. In performance, of course, some choice must be made, and actresses and directors have made just about all of them, from bewilderment to anger to humble submission to lusty acceptance, none of them fully satisfying. In reading the play, however, the absence calls attention to itself, requiring us to ask: What would we do?

Here the parallel with Esther is at its most profound. The Megillat ends with Mordechai and Esther audaciously proclaiming a holiday to commemorate the Jews’ deliverance, apparently usurping divine prerogative once more. But the talmudic sage Rava interprets the Jewish acceptance of this decree far more broadly. While at Sinai the Jews were compelled to accept the Torah or be buried under the mountain, he reads the voluntary acceptance of Esther 9:27 to refer not merely to the observance of Purim but to the Torah as a whole. In Rava’s production, as it were, despite all she has seen of the duke’s devious ways, Isabella says yes—not in stoic submission but in partnership.

In a sense, tradition asks us to do the same every year. We’ll finish playing Purim’s game of hide-and-seek, unmask ourselves, and sober up. And then, within the bare month that Hamlet’s Gertrude took to wed once more, we will sit around the table reading another book about another deliverance. And even though we remember the cruelty of the lottery on which our fate rested a month earlier, we will boldly claim that we ourselves saw that blooded Nile and blackened sky, the fiery pillar and split sea, and will embrace God’s manifest presence.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Working One’s Way Out

"When I first read Winter Vigil over a year ago, I was swept away; I hadn’t read any contemporary writing as good in a long time. I hadn’t known Steve Kogan could write like that. I hadn’t, it turned out, known very much about him."

Happy Is the People Who Knows the Blast

Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim of Sudilkov learned Torah with his grandfather the Ba’al Shem Tov, who later visited him in dreams. In the Degel Machaneh Efrayim, he gave the shofar blast a radical Hasidic meaning.

What . . . Him Worry?

How did Abraham Jaffee, raised in the shtetl of Zarasai, became one of MAD magazine's most prolific and recognizable cartoonists?

A Party in Boisk

The bodily joy a group of Boiskers took in fulfilling the commandment to study Torah is still surprising, and that may have something to do with the Torah they chose to study.

gershon hepner

While I agree fully with Millman that Ahasuerus is comparable to God, and Mordecai and Haman can be seen as his good and bad angels, I think, unlike Millman, that the megillah's author made this allegory intentionally. I demonstrate the following in my book Legal Friction that the Book of Esther satirizes the court of Ahasuerus in order to criticize the Judeans who remained in the Persian empire despite the return to Jerusalem of a saving remnant. I write on pp. 218-220:

There are allusions to the tabernacle in the names of Mordecai and Esther (see Lipton, Longing for Egypt, 72–76). מרדכי , Mordecai, recalls the מר־דרור , myrrh droplets (Exod. 30:23) (the preferred translation chosen by W.H.C Propp, Exodus 19–40 [New York: Doubleday,2006], 481–82), in the tabernacle, because the Aramaic translation this term, ,מירא דכיא used by Onqelos resonates with מרדכי , Mordecai; this allusion is mentioned in B.T. Hullin 139b and Megillah 10b. The original Hebrew name of Esther, הדסה , Hadassah (Est. 2:7), means myrtle (Isa. 41:8, 19; 55:13; Zach. 1:8, 10, 11; Neh. 8:15), and may be an allusion to בשמים ראש (Exod. 30:23), mentioned immediately before the מר־דרור , myrrh droplets, and considered by Megillah 10b to be an allusion to Mordecai. This term is commonly translated as ‘chief of fragrances’, but may denote a bitterness within the fragrances since ראש can denote a bitter and poisonous herb (Deut. 29:17; 32:32, 33; Jer.8:14; 9:14; 23:15; Hos. 10:4; Amos 6:12; Ps. 69:22; Job 20:16; Lam. 3:5). Est. R.6:5 seems to have been aware of the connection between הדסה , Hadassah (Est. 2:7), and בשמים ראש (Exod. 30:23), since it attributes the name Hadassah to the fact that the myrtle has a sweet fragrance but a bitter taste. The Talmud probably also recognizes this allusion when it declares that on Purim every Jew is obliged לבסומי , to make himself happy with wine (B.T. Megillah 7b). I consider this commandment to be an encouragement for every Jew to feel like the person Exod. 30:23 describes as בשמים ראש , whether this term applies to Mordecai or Esther, or both of them. It seems to me to be likely that the author of Esther links Mordecai and Esther to the fragrances used in the tabernacle in order to make a hidden polemic against the Judeans who regard the בירה , palace (Est. 1:2, 5; 2:3,5, 8; 3:15; 8:14; 9:6, 11, 12), in Shushan as the equivalent of the temple in Jerusalem. The Chronicler denotes the temple with the word בירה , palace (1 Chron. 29:1, 19), which also denotes a fortress near Jerusalem (Neh. 1:1; 2:8; 7:2).

Many words in Esther are associated with the tabernacle, narratively the forerunner of the temple, in Exod. 25–40.תפארת , glory, denotes Ahasuerus’s majesty (Est. 1:4) as it denotes the majesty of the High Priest’s garments (Exod. 28:2). Three words in Est. 1:6, תכלת , blue-violet, ארגמן , purple,and בוץ , byssus, also appear together with חור , white material, discussed below, in Est. 8:15, describing Mordecai’s garments. These words are all associated with the tabernacle narratives, and also with the temple-hangings in 2 Chron. 3:14; שש , byssus, in Est. 1:6appears in the tabernacle narrative but not in Chronicles. טבעת , ring (est. 3:12; 8:8 [×2],10), appears frequently in connection with the tabernacle, and the verb חתם , seal, associated with the word טבעת , ring, in Est. 3:12; 8:8 [×2], 10, recalls the word חותם , seal,in Exod. 28:11, 21, 36; 39:6, 14, 30. כלים , vessels, denoting the vessels used in Ahasuerus’s banquet (Est. 1:6 [×2], is also used to denote the vessels of the tabernacle (Exod. 27:19; 38:3) and Second Temple (2 Chron. 28:24 [×2]; 36:10, 18; Neh. 13:9; Dan.חור .( 1:2 , white material (Est. 1:6; 8:15), is also the name of Bezalel’s ancestor (Exod. 31:2; 35:30; 38:22; 1 Chron. 2:19, 20, 50; 4:1, 4; 2 Chron. 1:5). לשקול , to weigh (Est. 4:7), alludes to the שקל , shekel, associated with the tabernacle (Exod. 21:32; 30:13 [×2],15; חצר .( 38:26 denotes the courtyard of Ahasuerus’s palace (Est. 1:5; 2:11; 4:4, 11; 5:1,2; 6:4) and is frequently used to describe the courtyard of the tabernacle. Lipton points

out that לבד , unless (Est. 4:11), used in connection with the death of people who approach

the king without being called, alludes to the בד , linen (Exod. 28:42, 43), which the priests must wear, on pain of death, when they approach the altar (Longing for Egypt, 74–75).

The festival of פורים , Purim (Est. 9:26 [×2], 28, 29, 31), recalls the day of הכפרים , the

expiations (Lev. 23:27, 28), known as Yom Kippur, as indicated in Lev. 16:29–34, not

only because of the verbal similarity noted in Tiqqunei Zohar 57b but because it is

associated with the casting of a הגורל , the lot (Est. 3:7; 9:24), recalling the גורל , lot, thatd etermined which of two goats would be sacrificed and which sent away as scapegoat (Lev. 16:6, 8 [×3], 10).

The names of Mordecai and Esther clearly have Babylonian origins, Mordecai being related to Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, while Esther is related to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. Mordecai and Esther therefore echo Joseph,whose assimilation was accompanied by his acceptance of an Egyptian name, Zaphenathpaneah (Gen. 41:45), something the rabbis say the Israelites did not do when they were in

Egypt (Lev. R. 32:5; Num. R. 13:20; Song R. 4:25). (It should be noted that Joseph woregarments of שש , byssus (Gen. 42:42), like the ones mentioned in Est. 1:6.) By linking the names of Mordecai and Esther to the fragrances used in the tabernacle the author of Esther implies that the Judeans in Shushan were so assimilated that they came close toconfusing the בירה , palace, in Shushan with the temple in Jerusalem.

Vashti’s refusal to show her beauty, presumably her nakedness (Est. 1:11), creates a contrast with theJudeans, represented by Oholah and Oholibah in Ezek. 23, who do reveal their nakedness.This is considered a cause of exile in Lev. 18 and 20 (Lev. 18:28; 20:22–23). Theauthor of Esther hopes that whereas Ahasuerus cannot revoke his decree to punish Vashti, God will intervene to end the Babylonian exile.

The links between the names of Mordecai and Esther and the tabernacle therefore reflect a hidden polemic against longterm diaspora. Esther’s revelation of her nakedness to the king may reflect the ‘worldupside-down’ motif that permeates the book, mentioned in Est. 9:1.

For links between Ahasuerus’s palace and the tabernacle, see D. Lipton, ‘The Woman’s Lot in Esther’, in Bodies, Lives, Voices: Gender in Theology (ed. K. O’Grady and J. Gray; Sheffield:Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 133–51.

The Book of Esther not only allegorizes Ahasuerus, Mordecai and Esther in the manner that Millman suggests, but sees them all negatively, being a hidden polemic not only against the Judeans who did not return to Jerusalem when Darius made this possible, but also against the injustice of this exilic world, a world in which the true God is absent, just as Measure for Measure is a hidden polemic against the world in which its protagonists live, where the true God is also absent, and has been replaced by a monarch, Queen Eizabeth, who does not follow the laws of God.