Jeremiah, Ben-Gurion, and Hillel Halkin

In one of David Ben-Gurion’s last addresses on the Bible, an essay entitled “The Monarchy and the Prophethood” delivered in October, 1968, the old, former prime minister meditated on Yehuda Leib Gordon’s “Zedekiah in the Dungeon”—the very poem that Hillel Halkin beautifully translates and deploys to criticize the descent of Israel into religious fanaticism. In Gordon’s poem, Israel falls because Jeremiah forces the king to rule according to the law of God and not according to political necessity. In “The Monarchy and the Prophethood,” Ben-Gurion says that, as a young man, he had sided resolutely with Gordon and against the prophet Jeremiah. But his views changed:

Only after I immigrated to Israel—62 years ago—and read the Bible here, did I know and understand that justice was on the side of the ‘Prophets of Rebuke’. . . I learned two things from the reality of life in the land, and from the Bible which I have read in an altogether different light since I came to the land: 1) that words alone, even the most beautiful words, if not accompanied by appropriate deeds, have no significance at all. As a result, I was compelled to say at some international gathering that I am no longer a “Zionist.” And 2) that Moses was correct. We are the smallest of nations and, thus, we must be a special people. Only our superior quality has sustained us. We succeeded in the Six Day War because we succeeded in building up a special army. And we need not fear evil if we also succeed in establishing a special government.

I take Ben-Gurion to be saying that he had realized that a purely secular government would not be enough to motivate the kind of action necessary to survive in a hostile land. The principles of justice illuminated by the Bible would have to help guide the Jewish state. Though Israel would have to learn the arts of war and government as other nations had, it could not simply aspire to be like any other nation. To be sure, Ben-Gurion’s return to the Bible did not lead him to return to the apolitical legalism that he thought typified the Diaspora.

But Ben-Gurion saw there was a tradition of political prudence within the Bible in particular—and within the Jewish tradition on the whole—that could be recovered. Ben-Gurion defends Jeremiah from Gordon’s charge that the prophet was a fanatic who brought about the destruction of Israel through his insistence upon religious ritual and law. The text does not state, according to Ben-Gurion, that Jeremiah opposed the Israelites fighting on the Sabbath if the circumstances warranted it. In fact, as Ben-Gurion writes, “Jeremiah opposed warring against King Nebuchadnezzar on week-days as well, because he knew the balance of powers [emphasis added] and was certain that the Jews would be routed.”

Ben-Gurion ultimately understood that the principles of the religion of Israel would inevitably have some role in forming the State. The power politics of Zionism had been indispensable, but it was not enough. It was because of this that the founder of the secular Zionist state once found himself telling an international conference that he was not a Zionist, and recalled precisely this moment when he returned to Gordon’s poem after a lifetime in politics.

To be sure, the history of Israel has been full of surprises. Halkin’s summary of the growing power and confidence of different kinds of observant Judaism in Israel would have astonished Ben-Gurion no less than Jabotinsky, who, as Halkin taught us in his biography of the early Zionist leader, would have accepted a state of “gefilte-fish eating” if it came down to it, but certainly did not want it. But I do not believe this represents a tragic overturning of the humane secular Zionism of which Halkin has been so eloquent a spokesperson.

It was simply inevitable that Israel would, over time, become more Jewish. A study of the Yishuv and early Israel shows how swiftly rigid ideological Zionism accommodated Jewish realities. Some ideological architects of Zionism sincerely thought that Judaism could be supplanted by a purely Hebrew state or Zionist state. And the early governments of Israel certainly engaged in some mild repression of traditional practices of olim. But Israel very quickly made its peace with the traditionalism and religiosity of many of its immigrants. From the 1970s onwards, there has been a steady increase in Judaism in Israeli public life. The fact that the country has, in many ways, become more rather than less liberal during this period, and especially since the 2000s, should give ardent secularists pause.

I don’t think that Israel is falling blindly over a cliff, but I would be the last person to deny that certain kinds of current religious opinion or sentiment threaten the kind of liberal and humane Israel that both Halkin and I ardently want. The difference between us is that I think that liberalism and Judaism can be fruitfully, if not perfectly, combined—and in fact are being combined by the majority of religious people in contemporary Israel. Halkin, on the other hand, seems to think that Judaism, in its natural milieu, must become both obscurantist and fanatical.

I do not deny that there is reason for concern. Itamar Ben-Gvir is, after all, a minister in the government. There is certainly a growing undercurrent of ethnonationalism and chauvinism on the right, as well as increasing ideological rigidity on social and cultural issues—witness the stupid and impolitic campaign to dramatically narrow the standard for who qualifies for the Law of Return. (It’s worth remembering that a broad, flexible attitude to the question of “who is a Jew?” perhaps saved Israel during the mass emigration from Russia in the 1990s.) And yet, there is a growing and vibrant religious center in Israel that combines adherence to the religion of Israel and the State of Israel with a belief in the dignity of all human beings and a respect for the rights of all.

The works of the early Zionist men of letters like Y.L. Gordon should be cherished. Yet in these matters I suggest that David Ben-Gurion may be a better guide. Acknowledging that our biblical inheritance makes us “a special people,” with a moral and spiritual inheritance to live up to, will not lead Israel to the fate of Zedekiah’s kingdom.

There is a vital role here for Zionist scholars as well, one which Hillel Halkin has often played in his long, distinguished career. We must reconstruct the rich intellectual tradition out of Jewish sources that show how toleration and respect for the rights of all individuals, regardless of religion or background, is an expression of political Judaism and not a prudent deviation from it.

Suggested Reading

Paradox or Pluralism?

Walzer’s paradox of liberation, if that is what it is, is that religion is back, or that despite the extraordinary success of secularizing revolutionaries it never quite went away.

Like a Son of Man

Who gets to anoint the Messiah?

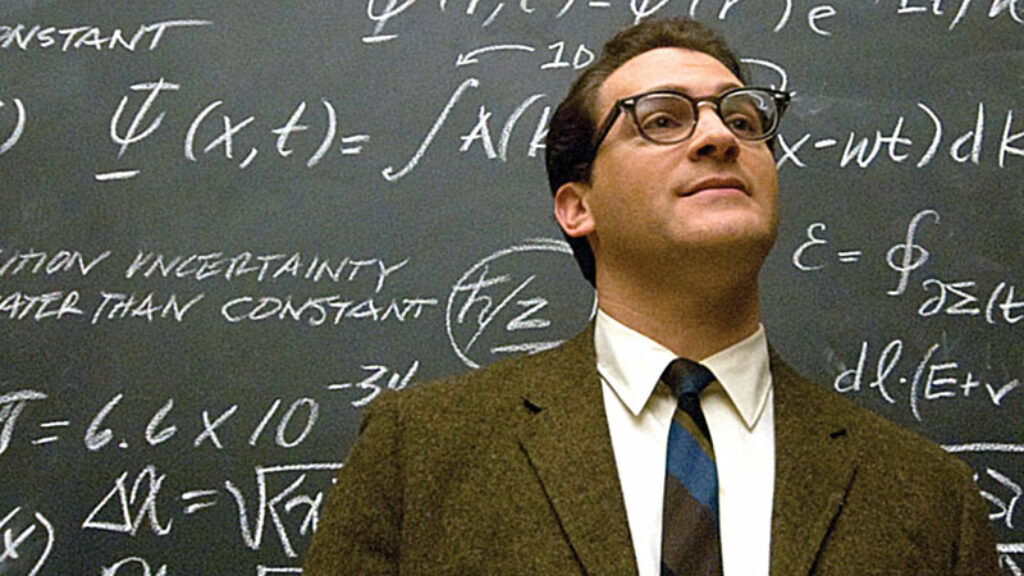

A Serious Comedy

In A Serious Man, the Coen Brothers found a way to address the realest of subjects—their own childhood, their own sense of Judaism—without sacrificing their style; they “grew up” without losing their humor.

Eichmann, Arendt, and “The Banality of Evil”

Richard Wolin’s review of a new book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Arendt. His exchange with Seyla Benhabib on the banality (or not) of evil.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In