A Comic Megillah?

“There are no good children’s books on the Bible,” argued the astute cultural critic David Zvi Kalman, “because the Bible was not written for children.” I saw him post this a while back on Facebook and, on some level, it’s obviously true. The Bible, his assessment accurately reflected, contains Rated R elements including, but not limited to, violation of Jewish law, drunkenness, kidnapping, adultery, impalements, and war.

It is, in a word, graphic.

Which leads us to The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel – Esther, a graphic novel adaptation of Megillat Esther, including the full Hebrew text with translations, which overcomes the challenge of the Bible’s often graphic nature in clever, creative, and brilliant ways.

This is not the Megillah’s first representation in comic book form. JPS published J.T. Waldman’s black-and-white rendering, geared towards adults, in 2005. Waldman’s expressionist adaptation is densely packed and dizzying in its execution—all harsh lines and grimacing faces, with the Hebrew and English text scattered throughout in inconsistent styles and arrangements. The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel – Esther, meanwhile, aims squarely at the bat and bar mitzvah set—more Disney than Dante—with, like any good kids’ movie would have, much for parents to enjoy as well.

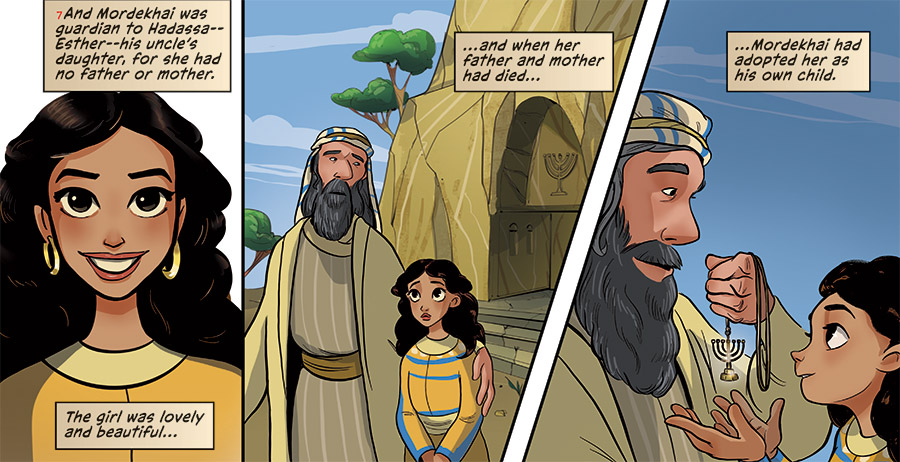

Koren Publishers previously entered the graphic novel space with its very popular Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel, written and illustrated by Jordan B. Gorfinkel and Erez Zadok. Gorfinkel, who was a long-time editor at DC Comics and manager of the Batman franchise, was joined by artist Yael Nathan, who has worked on the Star Wars Adventures comics series. In contrast to that work, the new graphic Megillah has the look and feel of a Jewish Disney cartoon and is far more linear and literal than the generation-spanning Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel.

Koren’s cartoon Esther could have been sketched by the artists who worked on Aladdin. The characters slide into body types familiar to viewers well-versed in the Disney Renaissance. Doe-eyed maiden heroine? Check. Broad-shouldered, arrogant antagonist sporting dastardly facial hair? Definitely. Corpulent, joyful, and relatively harmless supporting character and a sagely long-bearded mentor—yes and yes. For sharp-eyed readers trained on the Marvel universe’s easter eggs, there is even a Purim equivalent (hamantaschen hints?), built on a wealth of midrash, and effectively used to bring the literal text of the Megillah to visual life.

Thus, in the opening spread, a gargantuan Ahasuerus, king of Persia, stands proudly atop a globe wearing the Israelite High Priest’s Urim ve-Tumim, alluding to the midrashic teaching that the monarch possessed the looted Temple vestments and utensils. On the globe’s surface, despondent Jews walk—in a manner meant to evoke the Arch of Titus—from a fiery Temple in Jerusalem towards the palace in Shushan, over which the massive Ahasuerus is raising a toast in a golden lion-encrusted goblet, his other hand holding a scepter topped with the face of what would seem to be King Nebuchadnezzar II.

Throughout The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel – Esther, nuanced textual readings are rendered alongside rabbinic allusions and visual gags—sometimes in the same small panel. For example, the disobedient Vashti is taken from the throne room by palace guards, leaving it ambiguous, as in the text of the Megillah itself, if she is being executed for her disobedience or simply removed as queen. While she is dragged away there is a bubble above her that shows Ahasuerus as a stable boy, an allusion to the ancient Talmudic teaching that it was Vashti who had inherited the crown from her royal father, and that Ahasuerus originated from more humble origins. In what seems to be depicting Vashti’s revenge fantasy emerging from the artists’ imagination, stable-boy Ahasuerus has been stabbed with a knife and has an arrow in his back.

The tension the creators are navigating, often brilliantly, is a simultaneous translation on two fronts: Hebrew to English and textual to visual. Originality abounds in both. Thus the Book of Esther’s 2:19 mention of Ahasuerus holding a second competition for a new queen, even after Esther had won the first, is rendered in the graphic novel as “. . .a second time?! . . .” The punctuation absent in the original Hebrew is present here as a reflection of Esther’s bewilderment upon hearing the second competition’s announcement, and of her concern over losing her newly-acquired status. And, of course, the graphic novel visually represents figures for whom the specifics of appearance did not concern the Bible, which contains no illustrations. Embracing the shift to a different language and medium, rather than feeling restricted by it, is what enables the graphic novel to work as an engaging educational product.

That embrace and creative shift can be seen in the handling of the Koren Megillah’s more mature elements. Although the graphic novel is willing to engage with a certain level of violence (stabbings, hangings, and impalements are all depicted), the implicit sexual elements of the text are rendered as innocently as can be. The eunuchs are depicted as typical palace bureaucrats. The gathering of virgins for the king to find Vashti’s replacement seems as tame as a gathering of contestants on Persia’s Got Talent (contra Waldman’s more adult rendering, which has copious nudity). The harem where the women are kept seems like a nice spa.

Gorfinkel and Nathan handle the series of forced encounters with a sexually ravenous king much in the way that Walt Disney might have. When the text describes the maidens being called, the artists show only the back of a gown entering the throne room (“She would enter in the evening. . .”). In the following panel, the same hallway is shown darkened and empty (“…and…”), followed by a panel depicting the morning and the maiden walking away. (“. . .in the morning she would return to the royal harem. . .”)

Esther’s turn to spend time with the king is greeted with a full-page portrait of her in a white floor-length gown, a small flower tucked behind her ear, with rainbow colors refracted behind her as she holds a wine pitcher. She looks as wide-eyed as the The Little Mermaid’s Ariel discovering life beyond the ocean. Her life in the palace, while clearly dangerous, is not isolated and terrifying. As Esther strives to hide her Jewishness, keeping a menorah necklace neatly tucked away, she is aided by the kind palace staff. In a scene imagined by the artists, she is offered a skewer of pork, and when she declines, the young palace guard realizes that she’s Jewish (conveyed with a speech bubble depicting a Star of David). He assures Esther he’ll keep the doe-eyed queen’s secret.

However, in this rendering of the megillah, Ahasuerus is clearly never the true threat. The villain is Haman, whose name is always written in a spiky red font. When the wicked viceroy enters the plot, he is unsurprisingly depicted in line with rabbinic teaching: bearing a necklace with an idol on it. More jarringly, he looks like Gaston from Beauty and the Beast and sports a Führer-style mustache. Zeresh, his wife, has hair shaped like devil’s horns. And in case Haman’s facial hair was too subtle, his accusation against a “people scattered and dispersed. . . whose laws are different” is accompanied by panels of hooked-nosed Jewish figures playing with money and holding a Torah scroll. They could have been copied straight out of the Nazi publication Der Stürmer.

The Shoah imagery returns during Mordechai’s warning to Esther, which begins, “For if you keep your silence at this time….” The final Hebrew word of Mordechai’s speech, toveidu, is translated in four words: “will. . . be. . . lost. . .forever. . .” Each word descends along spiraling snapshots of scenes from Jewish history that depicts Esther as an exile from Spain, a refugee from Russia, a concentration camp prisoner, a Zionist kibbutznik, and a modern American—connoting the Jewish story whose unfolding will be sundered should Esther not act. When Esther reveals that Haman plotted against her people, his death and the death of his sons is accompanied by an image of Auschwitz. Beneath the Concentration Camp, Gestapo caps are crossed out with red ink.

The epoch-spanning imagery, a multiverse of modern midrash, is carried over from the Koren’s earlier graphic haggadah. The Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel depicted Natan Sharansky and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks crossing the split Red Sea, as well as “Dayenu” being recited by a colonial-era Jew and a shtreimel-bearing Hasid. The traditional text, Koren seeks to convey in its graphic novels, is as timeless as the Jewish people themselves. The text is one long story existing both within and beyond a specific historical context.

As in the beloved animated childhood classics in which the nightmare-inducing Ursula and Jafar are defeated, the horrors of the Holocaust pointed to in The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel – Esther are subsumed by celebratory soirees. The description of Haman’s plot having turned “from sorrow to happiness. . . from mourning to celebration” is accompanied by characters celebrating and emoting through speech bubbles consisting of emojis. In the final panel’s portrayal of Shushan’s Purim parade, a young woman identical to Esther wears Wonder Woman-style bracelets, a tiara with a cape, glasses, and a Star of David on her chest like Superman. Iron Man and Pikachu costumes can be spotted among the revelers.

While some parents may struggle to explain the Nazi allusions to curious preschool readers, and lament the lack of scholarly footnotes demarcating midrashic elements, The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel – Esther is, like Purim itself, an exercise in joy overcoming rationality. Perhaps, as Adele Berlin, who is thanked in the book’s back pages, has suggested in The JPS Bible Commentary: Esther, the Book of Esther itself is carnivalesque, a narrative meant to be taken as, well, comic.

Just as feasting turns to fasting which turns to feasting throughout the Megillah, The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel – Esther seems to be saying that Esther can be at once a Persian young woman taken from her home, a Disney princess in a fantasy, and an Israeli pioneer who overcomes Haman-Hitler.

The improbable story of Esther, like the improbable story of the Jews, the graphic novel Megillah argues, is just as an amazing a tale as Spider-Man, as astonishing as the X-Men. Belief must be suspended, imagination encouraged. The rough edges of violence, death, and despair are subtly rounded for children’s consumption, since it is they who possess the highest degree of light and happiness, and we do not want to not dampen it or them. The Bible might not have been written for kids, but Jewish continuity depends on the youth’s engagement with it—so Koren is arguing with their graphic novels. Our story won’t survive if it is deemed irrelevant by those to come. And because of this, we find ourselves every year gathering in synagogue—eight-year-old Pokémon alongside Mordechai, Wonder Woman alongside Esther—teaching children these stories that are not children’s stories but that must be taught—even if they are a little graphic.

Suggested Reading

Exodus and Egyptology

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel shows why the plagues were chosen and how the Israelites sang at the reed sea.

Spielberg’s Fable

A Spielbergian Fable with an Opaque Moral.

The Gentile Jewess

Am I Gentile? Am I a Jewess? Both and neither. What am I? I am what I am.” Muriel Spark at 100.

“Where They Have Burned Books, They Will End Up Burning People”

The surprising source for Heine’s prophetic remark that “where they have burned books, they will end up burning people” is a play about the fate of Muslims in Christian Spain.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In