Israel’s Declaration of Independence: A Biography

On December 12, 2022, an eleven-story banner depicting Israel’s Declaration of Independence appeared on the side of an office tower in Tel Aviv’s City Hall complex. Explaining the municipality’s decision to put it there, Tel Aviv mayor Ron Huldai said simply, “This is our way and these are our values.” Since then, Israel’s Declaration of Independence, whether displayed on banners, projections, in newspaper advertisements, or even acted-out signing ceremonies, has become a constant and generally calming feature of the otherwise heated conflict over the divisive issue of judicial reform.

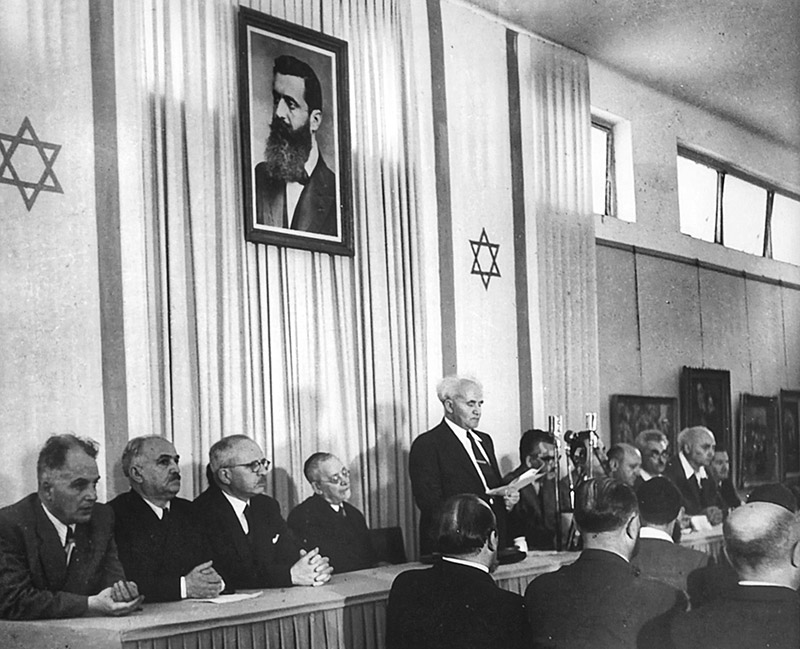

The text that David Ben-Gurion proclaimed upon Israel’s founding on May 14, 1948, is best remembered in contemporary Israel for two things. First is its stirring crescendo:

By virtue of our natural and historic right and on the strength of the Resolution of the United Nations General Assembly, [we] hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish State in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.

The grainy film footage of Israel’s first leader reciting this sentence from a dais backed by long flags bearing the Star of David is ubiquitous in Israeli life: from advertisements for Yom HaAtzmaut sales at shopping malls to campaign spots for political parties of all stripes. Posters of Ben-Gurion at the dais are sold at both tourist shops and high-end photo art galleries; they are mandatory office wall material for politicians. Like America’s Declaration of Independence, and perhaps more so, Israel’s Declaration is part of the consensus political culture.

The second aspect of Israel’s Declaration that maintains strong popular currency is its statement of political ideals together with a kind of informal bill of rights. It reads:

The State of Israel . . . will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

This admirable statement of ideals is what most Israelis think of when they say, “These are our values.” Amid war and turmoil, Israel’s founders thought to proclaim the inherent rights and freedoms of citizens and to emphasize the rights of minorities—even minorities with whom they were then at war.

Israel’s Declaration of Independence stands out for its citizens not only because it is a noble founding statement but because there are very few authoritative texts that articulate Israel’s first principles to be found. As is well known, Israel is a constitutional democracy of sorts without a single urtext constitution, relying instead on a patchwork of Basic Laws and judicial decisions. This is the case precisely because agreeing on a constitution in such a fractious, religiously divided, and embattled state has always seemed impossible. The Basic Laws passed during the 1980s and 1990s, which touch on matters of citizens’ rights and serve a kind of constitutional role, tend to hearken back to the Declaration, citing its text.

Israel’s courts have themselves recognized the importance of the Declaration of Independence as an articulation of what an early landmark court case called “the vision and credo” of the nation. There have even been modest efforts to legislate the Declaration itself as a Basic Law of the state. Five years ago, it was proposed as an alternative to the Jewish State Law that was ultimately passed, and the suggestion to revive a similar effort has been made again amid the recent political controversies.

All of this only further increases the urgency of unpacking the meaning of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. What are the natural and historic rights of Israel to which Ben-Gurion appealed? What does “freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel” mean? And why does the Declaration invoke “freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture” but not, for instance, freedom of speech or for that matter inherent rights to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness? And while there can be no doubt that the Declaration expresses a democratic vision, why doesn’t the word “democracy” appear in its text?

The answers to these questions involve not only Ben-Gurion and distinguished political colleagues like Golda Meir and Moshe Sharett but also civil servants, a young Tel Aviv lawyer, and a learned Conservative rabbi from America. The details of this story are fascinating, but it also touches on vital questions being debated in Israel right now. What does it mean to be a Jewish state, a democratic state, and a strong sovereign state? How do these ideas hang together?

The first draft of Israel’s Declaration was a stunning document, a unique blend of the Enlightenment ideas of the American Revolution, the biblical promise of the covenant between God and the Jewish people, and the accomplishments of the Yishuv, the pre-State Jewish settlement.

The draft began “Whereas this Holy Land has been promised by the Lord God to our fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and to their seed after them,” and went on to summarize the history of Jewish sovereignty and exile. It then asserted:

The true, ancient, and indubitable right of the Jewish People to reconstitute their state in this Holy Land, and to assume among the Powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of God and Nature entitle them, to secure and enjoy the inalienable rights to Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

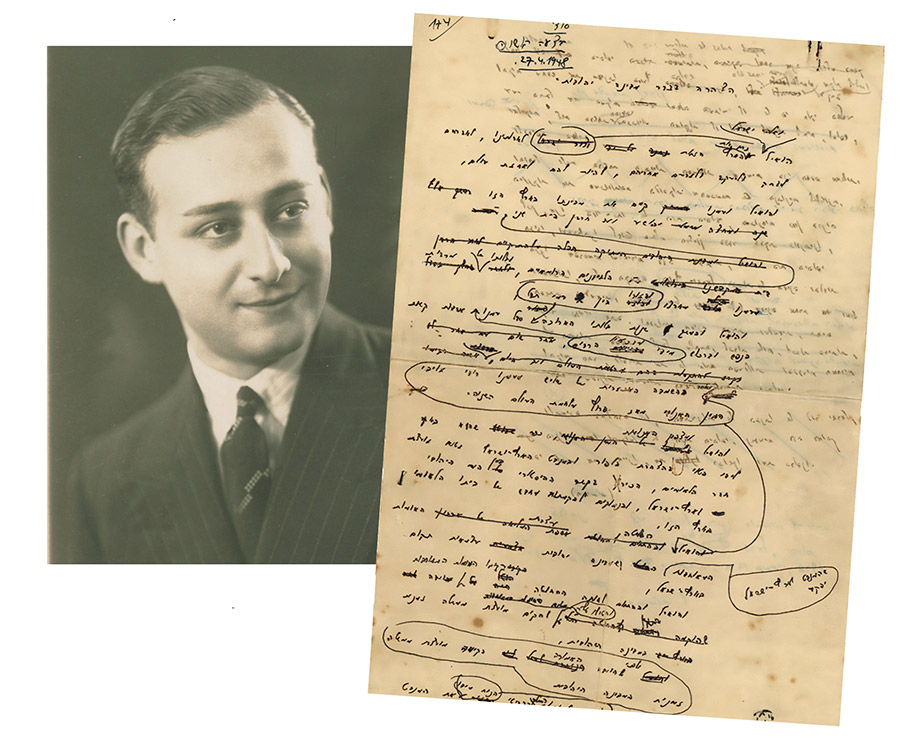

This statement of American-style natural rights together with a literalist assertion of the biblical basis of Zionism was bound to surprise a Yishuv leadership dominated by socialist secularists from Eastern and Central Europe. It was drafted—first in English and then in Hebrew translation—by Mordechai Beham. Beham was a thirty-three-year-old London-trained Tel Aviv lawyer. In late April, he had been tasked by his boss, Pinchas Rosen, with writing a proclamation of independence that could be issued when the British left Palestine on May 15, 1948.

Beham, as related by family lore, was overwhelmed. He didn’t know where to begin, he worriedly told his family during Shabbat lunch on the first day of Passover, April 24, in Tel Aviv. And so, he went after lunch to consult with a quirky, learned rabbi from America named Shalom Tzvi (Harry) Davidowitz who lived down the street and had an outstanding collection of English literary and political classics. Davidowitz, who had been a Conservative rabbi in Cleveland, Ohio and an American Army chaplain before he made aliyah, spent his days in the promised land immersed in reading medieval philosophical texts and translating the works of Shakespeare into Hebrew.

Beham spent the rest of the day with Davidowitz in his library. By the end of it, he had copied out the stirring first two paragraphs of the American Declaration of Independence, which argues that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed” and offers the view that humans have “unalienable rights.” He had also highlighted the American Declaration’s concluding paragraph, which explains that independent states may “levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and . . . do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do” in the service of protecting the inherent rights of the citizens. He had, in short, extracted the essence of the American doctrine. We know this from original notes, written in longhand, that Beham left behind among his private records.

Beham also copied the keywords from the English Bill of Rights of 1689: “true, ancient, and indubitable rights.” This description, Beham (and perhaps Davidowitz) clearly thought, applied to the Jewish people in their ancestral land as well as it did to the English.

Beham’s third major source was the beginning of Deuteronomy in the King James Version: “Behold, I have set the land before you: go in and possess the land which the Lord sware unto your fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to give unto them and to their seed after them” (Deut. 1:8). Finally, he copied out some language from the United Nations Resolution 181, passed by the General Assembly in November 1947, which called for a Jewish state, an Arab state, and an international Jerusalem in Palestine.

Beham’s declaration closed with the bracing Jeffersonian assertion that the signers of the declaration of the Jewish state were conducting their work under “firm reliance on the protection of divine providence.” When he translated his English into Hebrew, divine providence became Tzur Yisrael, the Rock of Israel.

Beham’s admirable first draft combined the American emphasis on natural rights, the British emphasis on the trial of these rights in the fires of history, and the simple Deuteronomic idea of the Jewish people upholding covenantal principles. Exactly how much Rabbi Davidowitz contributed to the draft either in English or in its Hebrew translation, if at all, we will never know. (A court case over the ownership of Beham’s draft texts, which had remained family heirlooms for decades, was inconclusive on this and many other points; the documents now reside in the Israel State Archives.) We will also never know whether an Israel founded on the basis of this draft would have been significantly different than the Israel of the last seventy-five years. Probably not, but it is interesting to imagine a counterlife for a modern Jewish state founded on its basis.

For many decades, the story of the first draft of Israel’s Declaration remained largely unknown. Beham returned to private legal practice and died an unfamiliar figure to the wider Israeli public, though he was remembered by the best informed observers of Israel’s founding and his close colleagues, including Uri Yadin. It was only in the 1990s, with the work of the Israeli legal scholar Yoram Shachar, who discovered Yadin’s diaries and the documents then held by the Beham family (and much else), that the roots of Israel’s Declaration of Independence came fully into view.

As it happened, Beham’s document was soon altered beyond recognition. The subsequent drafts of Israel’s Declaration of Independence expressed a more thoroughly Labor Zionist view of Israel’s founding. Written by Tzvi Berenson, a Labor Party jurist and future Supreme Court justice of Israel, and based on the work of Beham’s colleague Yadin and others in the Legal Department (including Beham himself), the second major draft of the Declaration proclaimed independence “by right of the unbroken historical and traditional connection of the people of Israel to the land of Israel, and by right of the labor and sacrifice of the pioneers.”

It also declared the founding of the state using a new and more complicated formula:

We . . . hereby proclaim the establishment of a Jewish, free, independent, and democratic state in the land of Israel, within the borders delineated by the General Assembly of the United Nations, with all the rights and authorities that the laws of nature and international law grant to independent states.

And in place of Beham’s account of the covenantal origins of the Yishuv’s rights in the Land of Israel, Berenson cited a vaguer “historical and traditional connection.” He continued to call the state a “Jewish state,” as all drafts did, but indicated little to nothing about what this might mean.

In place of Beham’s turn to the inherent rights of the individual, Berenson justified individual rights on the basis of the “labor and sacrifice of the pioneers,” a doctrine that seemed to combine the ideas of John Locke with the Labor Zionist spiritualist A. D. Gordon. However, Berenson’s draft also replaced Beham’s doctrine of individual natural rights with a simple list of social and political rights that the state would bestow on the people.

The catalog of rights that Berenson and the Legal Department assembled would, with a few key modifications, make its way to the final text of Israel’s Declaration. It was based on a text called the “Declaration on the Founding of the Government” written principally by the Labor Party newspaper editor and future president Zalman Shazar in early April.

Shazar’s declaration had been issued by the Va’ad ha-Po’el ha-Tsioni, the highest executive body of the various organs of World Zionism, at the conclusion of a tense weeklong meeting in which all meaningful political authority was officially transferred away from the old Zionist NGOs in Europe, the US, and the UK to new political bodies in the Yishuv. It culminated in Ben-Gurion gaining authority to create an executive council of thirteen decision-makers called Minhelet ha’Am and an oversight body called Moetzet ha’Am. Minhelet ha’Am would debate crucial issues in the run-up to independence. The Moetzet ha’Am would barely meet beyond ratifying the Declaration of Independence.

Shazar had written that the future state would do the following:

Be a state of justice and of freedom, of equality for all its residents, without respect to religion, race, sex, and land of origin, a state of the ingathering the exiles and the blossoming of the wilderness, a state of uprightness and understanding, and the vision of the prophets of Israel will illuminate the way for us.

Shazar’s inspiring words expressed a wide, and in fact almost universal, consensus in the Yishuv.And yet, it was silent on vital questions. Where do rights come from? How do freedom and equality relate to one another? Most significantly, how do liberty, equality, and the idea of a Jewish state fit together? The text has beautiful sentiments, but unlike Beham’s draft, it does not argue that the inherent rights of individuals are a part of the Jewish political heritage, though it does appeal to the vision of the prophets of Israel for inspiration. The catalog of rights in Berenson’s draft, and the ones that followed, had a different origin story: they were written largely to satisfy a pressing political need.

United Nations Resolution 181 had attached a whole host of conditions that Jewish and Arab states would have to meet if they were to be recognized. Shazar ascribed many of those attributes to the state in his text, likely to show that the state would comply with Resolution 181.

Of course, Resolution 181 was a dead letter. Both the Arabs of Palestine and the surrounding Arab states rejected it, and the War of Independence began immediately after its passage. However, the United States remained formally committed to the resolution, so it was at the forefront of the minds of the leaders of the Yishuv in the final weeks leading up to May 14, 1948.

The draft of Israel’s Declaration of Independence produced by Berenson and the Legal Department was delivered to Ben-Gurion and the rest of Minhelet ha’Am on May 11, 1948. In the days and hours leading up to the end of the mandate on May 14, the members of Minhelet ha’Am had their hands full, to say the least. On the borders of what would soon be their state, multiple Arab armies were assembled and planning to invade as soon as the British left. In Washington, at the highest levels of the State Department, a campaign against Jewish independence was underway. Still, these pressing dangers didn’t obviate the need to deal with more formal questions, including what the name of the new state would be (“Israel” was chosen, with surprisingly limited enthusiasm). And more importantly, what should be done about United Nations Resolution 181? Should the state be declared on its basis? If so, it would mean making firm commitments on matters like the UN-mandated borders as well as an international process of managed sovereignty, which did not envision simple and immediate independence.

This debate divided the council. Israel’s future foreign minister (and second prime minister) Moshe Sharett advocated for a Declaration of Independence in line with the UN process. Ben-Gurion argued for seizing the moment and creating facts on the ground.

After seeing the text by Berenson as well as a draft Sharett had brought from New York written by the distinguished legal theorist Herschel Lauterpacht, the council tasked Sharett and a subcommittee to compose a new draft of the Declaration. With the help of his colleagues, Sharett wrote a long draft that followed the Legal Department’s text when it came to domestic matters and Labor Zionist ideals but emphasized the United Nations process and other diplomatic arguments to satisfy America and the world powers.

Sharett’s draft was subject to withering criticism on all fronts, but the UN question was central. Ben-Gurion told his colleagues that they simply had to declare a state—“to go all the way,” in the words of Golda Meir—since neither the Arabs nor the UN had held up their side of the bargain. To make his case, Ben-Gurion drew on Lauterpacht, who had argued that the provisions of UN Resolution 181 were no longer valid because of its flat rejection by the Arabs, but the principle of the right of Jewish statehood that Resolution 181 had affirmed remained in force. Therefore, “the assumption of sovereignty must now be brought about by the Jewish people itself.” In doing so, Ben-Gurion argued that they should recognize the principle of Resolution 181, without committing to its specifics.

This was perhaps Ben-Gurion’s finest accomplishment in his finest hour. As the great Israelinovelist S. Y. Agnon would later put it:

I wanted a Hebrew State, but if I had been asked at the moment of the proclamation of the state whether to declare independence or not—I would have demurred. And it’s clear to me that no one else amongst us would have finished the job. Ben-Gurion, who I had previously erroneously underestimated, wasn’t intimidated—he did it.

Beyond the all-important question of sovereignty, debate on the matters that would roil Israel in the decades to come were surprisingly limited. Meir Grabovsky insisted that freedom of language, which had not appeared previously, be included in the Declaration. Otherwise, there was little discussion about the nature or origin of individual rights. Although the Mapam activist Mordechai Bentov had complained about the early drafts on precisely this ground—“I don’t find in these paragraphs the expression of the natural rights of our people to live freely in our homeland”—he did not suggest an alternative.

Much, maybe too much, has been made about the absence of the word “democracy” in Israel’s Declaration of Independence. It had been included in most of the drafts composed by Berenson and the Legal Department but had been deleted by Sharett. Perhaps because it is clear throughout that the document was declaring the independence of both a procedurally democratic state (there would be voting) and a substantive democracy as well (there would be equal protection of rights), and perhaps because time was so short, this, too, was not discussed.

Even more surprisingly, the debates over religion and state were quite limited. Aharon Zisling, an ardent secularist, objected to Beham’s (and perhaps Rabbi Davidowitz’s) invocation of the “the Rock of Israel,” which was almost all that remained of the first draft of the Declaration:

I agree to some wording that makes mention of the foundations of Jewish belief. I do not need to quarrel. However, it is not necessary to force me, and those like me, to declare “I believe.”

Rabbi Aryeh Leib Fishman, on the other hand, wanted to invoke divine guidance with the more theological or messianic phrase Tzur Yisrael ve-go’alo (Rock of Israel and Redeemer). But Ben-Gurion insisted that Tzur Yisrael was, in fact, a perfect nondoctrinal compromise:

It seems to me that we all believe, everyone in his own way and according to his own understanding. . . . I know what the Tzur Israel that I have faith in is. Surely my friend on the right knows in whom he believes, and I also know how my friend on the other side believes in it.

Ben-Gurion had kept the phrase in the document, but he hadn’t put it there. It was from the Beham draft that he never saw. Now, after this somewhat desultory debate, it was left to Ben-Gurion and his drafting committee, on the night of May 13, 1948, to decide the final wording of Israel’s Declaration of Independence.

Ben-Gurion had good intelligence that armies of the surrounding Arab states would begin a full-scale invasion the next day, and he could not be certain about the fledgling state’s prospects in a test of arms. But he also knew the Declaration was a unique moment, which had to, in his words, express a “deep ‘Zionist and Jewish’ justification” for renewed statehood. Writing and editing into the small hours of the night, Ben-Gurion aimed to address the decisive question of a Jewish state.

Ben-Gurion’s Declaration of Independence proclaimed independence “by virtue of our natural and historical right.” Following Lauterpacht, he cited UN Resolution 181 for recognizing the irrevocable right of the Jewish people to a state. But he declared independence on the basis of the natural and historic rights of the Jewish people, not the United Nations process. Bechor Sheetrit, born to Moroccan parents in Palestine and the lone Sephardi member of Minhelet ha’Am, had challenged his colleagues on just this second issue of the historic Jewish right: “It’s impossible not to mention our book of books,” noting that “epicureanism”—the traditional rabbinic term for heresy—“amongst the people in Israel began not that long ago.” Ben-Gurion, an ardent reader of the Bible as well as Plato, wrote a new introduction that evening to answer Sheetrit’s challenge:

Eretz-Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people. Here their spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped. Here they first attained to statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.

These felicitous sentences describe a state for a particular people with a universal mission—a mission derived from the universal values of the Book of Books. Ben-Gurion’s Declaration does not say anything about what the Hebrew text calls these “treasures.” It had been hard enough to get the Zionist leadership to agree to include “the Rock of Israel,” and yet Ben-Gurion’s framing changed the document.

The Declaration went on to reproduce the list of political and social rights that previous drafters had largely adopted from the United Nations resolution:

[The state] . . . will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture.

However, here, too, Ben-Gurion made a small edit with major theoretical import. Earlier drafts had proclaimed the state would bestow (ta’anik) rights. Ben-Gurion had the language changed so that the state would ensure (te’kayem) rights since, as he would tell his colleagues, “Rights belong to the people.” In doing this, he had moved Israel’s Declaration closer to the view of rights that had been articulated by Beham (and perhaps Davidowitz), whose draft Ben-Gurion had not seen.

Though he said to his colleagues that the Declaration “did not have to be recited by schoolchildren in one hundred years,” Ben-Gurion seems to have known deep down that it would be. Israel’s Declaration presented a wholly mature doctrine on sovereignty. When Israel declared independence, it had no recourse other than to defend the Jewish people through a nation-state in a world of nation-states that had left the Jews to the most terrible devastation and suffering amid the Holocaust and the Second World War. That a new state called “Israel” would take up “the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own fate, like all other nations, in their own sovereign State,” as Ben-Gurion would write in an entirely novel formulation composed on the eve of independence, was neither fully accepted nor guaranteed in 1948. The main test was on the field of battle. But Ben-Gurion’s mobilizing words, and the political choices they expressed, helped make this a reality.

It is easy enough to point out shortcomings of the Declaration of Independence. Indeed, in later life, Ben-Gurion would often emphasize that the significance of the Declaration was its simple proclamation of independence and lament that “men of humane learning” had not been present to elaborate further on its other themes. The doctrine of inherent rights could have been more fully explicated. And though it goes some way to spelling out what a “Jewish state” might be, the Declaration certainly did not give a full answer; in fact, given the differing agendas of the people in the room, it could not.

The unfinished work and open questions explain much of today’s controversy. But they also point to a way forward. Israel’s Declaration of Independence expresses a necessary political vision for Israel: a strong sovereign state, a Jewish state inspired by Jewish ideals, but with no whiff of theocracy, and a free state guarding the inherent rights of its citizens. The Declaration was also itself the product of pragmatic political compromise, leaving elements of its political vision ambiguous. Despite these ambiguities, or perhaps even because of them, the Declaration is the modern Jewish people’s most important political text.

Israel is a Jewish state, a free state, and simply a state—but one whose mission is to protect both its Jewish and free character. That glorious inheritance not only galvanized the Jewish people in 1948 but continues to serve as a rallying point for Israelis to this day. Perhaps it is not only an articulation of the values of 1948 but also of lasting principles.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Genius of Bernard-Henri Lévy

Bernard-Henri Lévy's amour propre, while immense, does not quite extend to regarding his life as exemplary in its Jewishness, nor to tying all of his political actions to Judaism.

A Normal Israel?

Zionism has long based its claim to sovereignty on the universal right to national self-determination, and the phrase “like all other nations” has been incorporated into Israel’s Declaration of Independence, yet the goal of “normalization” has proven to be much more complicated than most early Zionists had thought.

You Shall Appoint for Yourself Judges

Was the once-head of Israel's Supreme Court a robust defender of human rights or a runaway judge who imposed his political preferences on a nation? Tom Ginsburg explores the legacy of Aharon Barak.

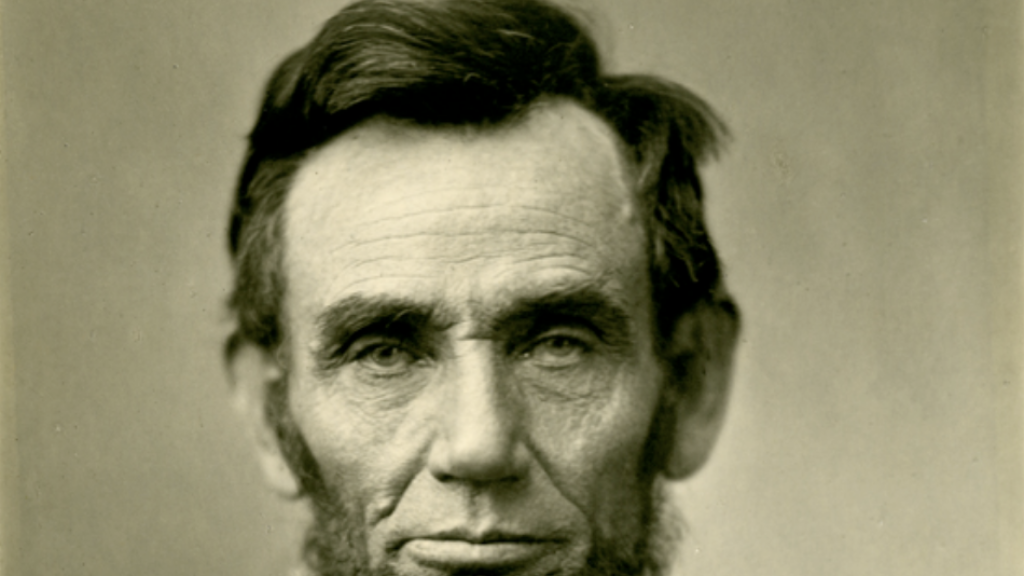

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

gershon hepner

DECENT RESPECT TO THE OPINIONS OF MANKIND

In the Declaration of Independence by the representatives of the United States you'll find,

in its first paragraph, the reason why the Founders wrote it.

While they assume the station to which laws of nature and its God entitle them,

they feel they have an obligation, which they state in words that are a precious gem,

and in the title of this poem that you're reading I have quoted.

This is that they're required to show---out of decency!---respect for the opinions of mankind,

except for those who don’t respect the views of others, which may be the reason why, when God told Abraham to found

a state for his descendants God told him that they would bless all nations who blessed them but curse those who cursed them for reasons that weren’t sound.

Gen, 12:1-3 states, according to the King James Version:

1. Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee:

2. And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing:

3. And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee: and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed.

This is the opening paragraph of the United States' Declaration of Independence, entitled In Congress, July 4, 1776, A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress Assembled:

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.