Indiana Jones and the Meme-ification of Nazis

In 1981, a creative team of three and a half Jews and the maker of Star Wars rendered one of the top action masterpieces in American cinema. Conceived in homage to old B-movie serials, Raiders of the Lost Ark raised this campy genre to sublime new heights. Of all the factors responsible for the inferiority of the fifth, and likely final, chapter of the franchise, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, the one that stands out is a sharp decline in the quality of its Nazis.

Though Harrison Ford (descended on his mother’s side from the Nidelmans of Minsk) is back as the titular swashbuckling archeologist, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas have ceded the respective roles of director and writer to James Mangold. (Philip Kaufman and Lawrence Kasdan, who rounded out the original ensemble as co-writer and screenwriter, haven’t touched the stuff since Raiders.) The result is a film propelled by nostalgia: a homage to itself, gingerly constructed around the capacities and melancholia of its eighty-year-old hero. Though some pains have been taken to correct the postcolonial sins of earlier installments, every other note is played in faint echo of its former glory: the bullwhip, the fedora, and the race against an evil foe to retrieve the object of power.

This last is the bedrock of an Indiana Jones plot: the Hitchcockian MacGuffin that everyone is chasing. Here it’s an Archimedean time machine that seems an unconscious self-revelation of the project’s necromantic impulses. It’s also a thoroughly secular MacGuffin. Those of the original trilogy—Raiders, Temple of Doom (1984), and Last Crusade (1989)—were supernaturally religious all the way down. Indy, in reverse order, sipped a healing draught from Christ’s Holy Grail, achieved worldly salvation through the ethereal radiance of Shiva’s sacred stones, and withstood the wrathful angels that came writhing out of a violated Ark of the Covenant.

Lucas was big enough to admit the Ark made the best MacGuffin, even though it wasn’t his idea. The inspiration came from Philip Kaufman, a comrade in the close-knit circle of now legendary New Hollywood filmmakers that also included Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola. Initiated into Ark lore as a child by his Uncle Morrie, “a revered Hasid,” Kaufman’s fascination intensified when he was treated for mononucleosis by Dr. Raphael Isaacs, a renowned hematologist who had also published a “spellbinding” monograph on the Ark as a sort of mystical ham radio. This ancient and sacred mystery box gave Raiders of the Lost Ark a narrative tension that was unrivaled in any of the following attempts to push lightning back into the bottle. When the Ark was forced open by Indy’s nefarious rival, it poured out the spectral horror of unbridled wrath, which was all the more compelling because its Master was the God of the Hebrews and its trespassers were Nazis. Admittedly, they were throwback B-movie Nazis, but the Ark accentuated their status as the enemies of God and His people, allowing the film to play upon the perversity of their desire to preserve and appropriate Jewish culture while exterminating the Jews. It was a satisfying, if ambiguous, revenge fantasy.

The Nazis of Dial of Destiny, by contrast, are products of the Indiana Jones series’ auto-nostalgia. As with the whip and hat, the Third Reich is just another callback to previous films, and a tortuous one at that. The bad guy is a broad-strokes Werner von Braun, who needs the Dial of Archimedes to rewrite history. Alfred Hitchcock famously said that it mattered very little what the MacGuffin was so long as it provided the requisite narrative jolt. In this sense, these Nazis are the film’s real MacGuffin, a vacant fabrication with none of the historical and Biblical resonance of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Raiders grounded its light entertainment in the living memory of Nazi villainy. It was a cartoon but one with moral and historical ballast. By contrast, the convolutions of Dial of Destiny emerge in a moment when Nazism is becoming just another rootless meme. To quote another intrepid Harrison Ford character, “I’ve got a bad feeling about this.”

Suggested Reading

East Meets West

Following the Six-Day War, the East German government and the West German far left demonized Israel time and again, often vilely equating it with the worst thing in their own nation’s history: Nazism.

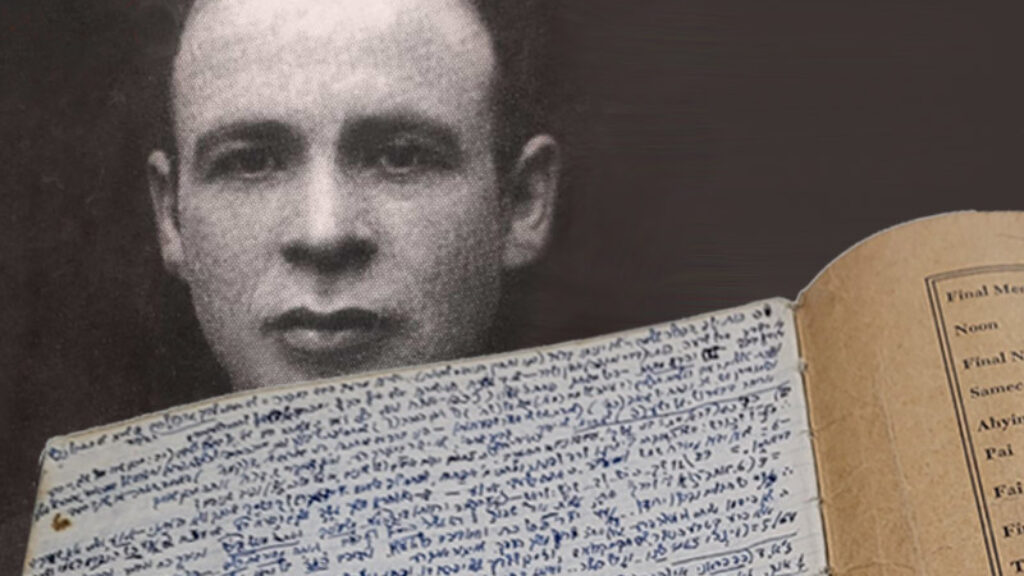

Think Over My Lesson and Try to Destroy It

When Levinas met a vagabond called Chouchani, he told a friend, “I cannot tell what he knows, all I can say is that all that I know, he knows.” Now that we have dozens of Chouchani’s notebooks, can we finally know what he knew?

The Law of the Baby

Mara Benjamin provides a deeply philosophical account, in loving, sometimes humorous detail, of what it is like to live under the Law of the Baby—and uses it, together with incisive readings of classical Jewish texts, to explore the nature of obligation in Judaism.

The Exilarch’s Lost Princess

In real life, or as much of it as historians can reconstruct, Septimania was a name for the region of southern France that included the Jewish populations of such venerable cities as Carcassonne, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Jonathan Levi leans on the most delightfully far-fetched version of these events in his latest novel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In