A Golem in Argentina

Of all the creatures that haunt Ashkenazi Jewish folklore—witches, estries, dybbuks—none sends a more thrilling shiver down the spine than the golem. Though he (and occasionally she) takes many forms and stalks many contexts, the most famous golem, often considered the original, was a hulking, semi-conscious monster formed of clay by Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the 16th-century rabbi of Prague, to protect the inhabitants of the Jewish ghetto from assaults by their Christian neighbors. To animate his mud man, Loew inscribed the Hebrew word emet, meaning“truth,” on its forehead.

It’s not surprising that the perpetually persecuted Jews longed for a supernatural protector. But the golem of legend was usually an unstable ally, devoid of intellect, with a problematic tendency to turn against his Jewish masters. The uncertainty of the golem’s allegiance was a painful reminder of the plight ofEuropean Jewry—so oppressed that even its protectors were unreliable. When the golem became uncontrollable, Loew destroyed it by erasing the aleph, the first letter of the word emet, from its forehead, leaving only the word met—“dead.”

Last year in the JRB, Michael Weingrad offered a learned overview of the golem in Jewish literature and contemporary popular culture—not all of it Jewish. The proliferation of golems in novels, comics, and even video games makes it unsurprising that another golem story would join the fray. But this one—a graphic novel written in French by Spanish speakers and set in Russia andArgentina, and pulled out of the vault for republication in English—is worth further comment.

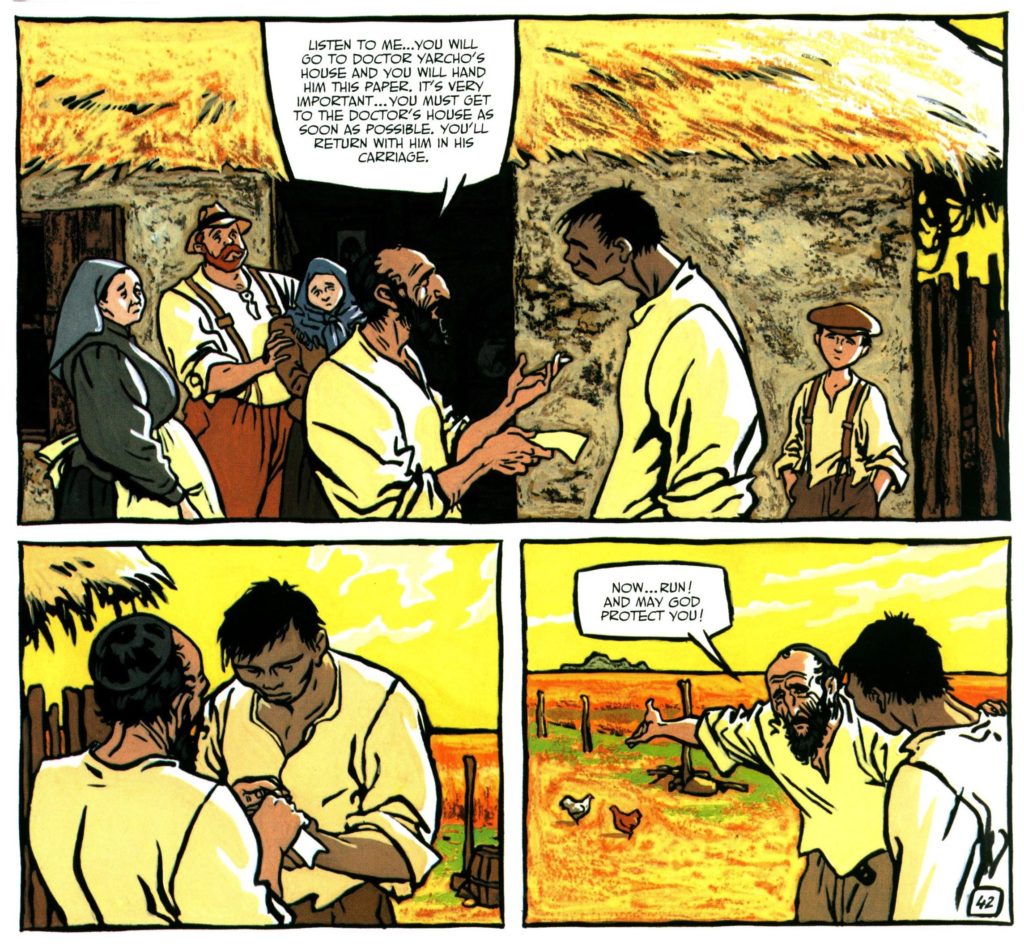

The Silence of Malka—story by Jorge Zentner and pictures by Ruben Pellejero (who have collaborated now on 15 graphic novels)—was originally published in installments in À Suivre (“to be continued”) in 1987, won Belgium’s prestigious the Angoulême International Comics Festival’s Best Foreign Graphic Album award a decade later, and has recently come out in English translation. Set in a Jewish settlement in Argentina at the end of the 19th century, the title character is a cute, plucky Jewish redhead. But more space is devoted to the story of Malka’s uncle, a poor, struggling farmer named Zelik, who is counseled by a mysterious, self-described prophet, Elias, to create a golem to help out with farm work and protect Zelik and his family from some hostile neighbors. (At the time, anti-Semitism was hardly unique to Russia; it existed in Argentina, too.) A hardy worker, the golem attracts the attention of the granddaughter of an indigenous medicine woman who begs her grandmother to create a love potion to win the golem’s heart. I won’t give away the ending, but suffice it to say things don’t go well.

The Silence of Malka is based on a relatively little-known historical event. In the late 19th century, Jews in the Pale of Settlement, a barren region where most Russian Jews were forced to live, were ravaged by a series of bloody pogroms. The pogroms were ignited in response to the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, a murder that, predictably enough, was blamed on the Jews. Amidst the bloodshed, a group of Russian Jewish leaders sent are presentative to Paris to investigate resettlement options. The emissary met with Argentine agents looking for immigrants to cultivate their large and sparsely-populated country. A deal was struck to send 135 families toArgentina. Unfortunately, the agents had swindled the immigrants, promising them land they had no authority to sell, and the Jews wound up living in railway cars, on the brink of starvation, in a remote Argentine province. They were saved by a wealthy Jewish French philanthropist, Baron Maurice de Hirsch, who sent a sizeable sum that enabled the refugees to form settlements in theArgentine Pampas where they established farms, built schools, and ultimately thrived. Over the next decades, 150,000 Jews would join this community which is today the seventh-largest Jewish population in the world.

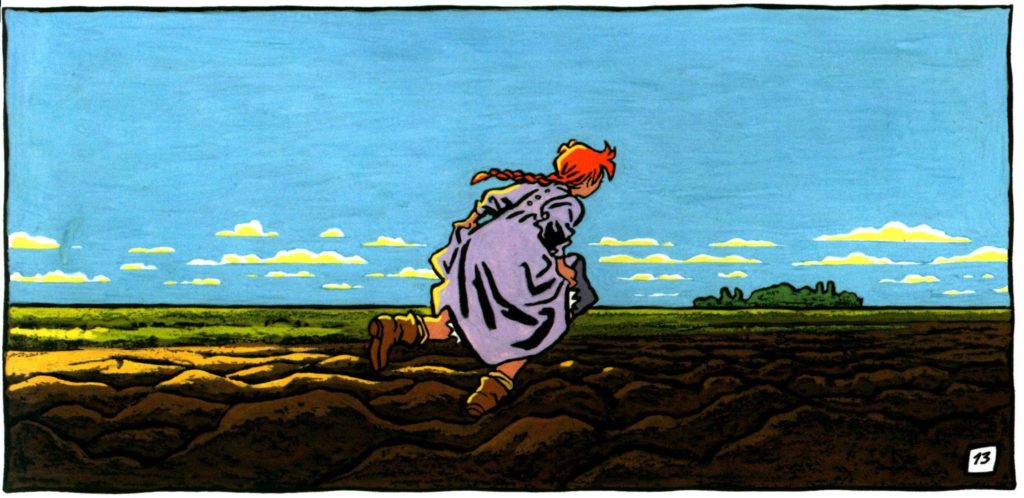

One of these original Jewish Argentine immigrants was Zentner’s grandmother, whose stories inspired The Silence of Malka. During the sea voyage to Argentina, a terrible storm erupted off the coast of Brazil. Zentner’s grandmother was nearly swept overboard, but her cousin grabbed her long red braids and hauled her back on deck, saving her life. In The Silence of Malka, the title character also has red braids.

While The Silence of Malka discusses this history in a preface, none of it figures explicitly in the story. As Pellejero explained in an interview in The Comics Journal, “History as a foundation for a plot interests me more than just a faithful description of an historical event.” Fair enough, but in this case a brief history of the Jewish Argentine settlements in the novel itself could have been a riveting addition.

The book’s golem is suitably scary, in many ways a standard monster: mute, ugly, massive. Like so many other traditional golems, he exists in an unsettling limbo between hero and villain. But he differs in that he is not immediately recognized as a monster—he passes for a person. (And this confusion drives much of the plot.) Perhaps this is the reason that this golem’s emet is inscribed on his thigh, hidden from view, rather than his forehead. This positioning might also allude to the famous story from the Torah in which Jacob wrestles with an angel, who strikes him in the thigh.

Since golems are supposed to be enigmatic, the golem’s lack of personality in Malka is not a major flaw. More troubling is how undeveloped Malka’s own character remains; she’s more a witness to the action than an active participant in the story. The “silence” of the title is not a misnomer. Nor do Malka and the golem ever really interact, which is disappointing.

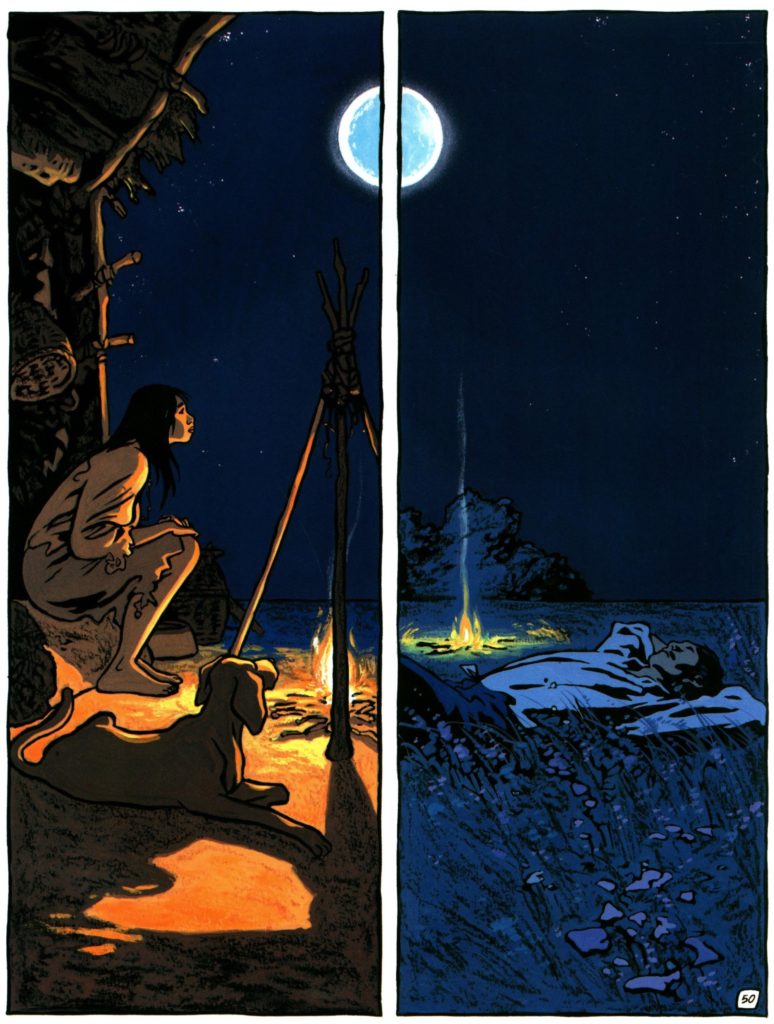

No matter the flaws in characters and plot, though, it’s the illustrations in The Silence of Malka that are the book’s crowning glory. Pellejero draws his golem in shades of brown, a huge figure with a sloping forehead, beetled brow and beady eyes, meagerly clad in ragged shirt and trousers. Despite his ungainly appearance, the golem exudes virility, sexual potency, evinced in one panel where we see the monster nude, taking his daily bath in a nearby river. Pellejero’s golem looks less European than aboriginal, with his dark skin, long neck, thatch of thick black hair; indeed, his depiction can be seen as trading on white stereotypes of the noble savage (as does the portrait of the wise and wizened medicine woman and her wild, beautiful granddaughter, who graces the book’s cover). If the drawing of the golem is somewhat problematic, so perhaps is the depiction of Jewish characters, especially Zelik who sports the kind of large hook nose often found in anti-Semitic iconography of the Jew—a little jarring in a book by a Jew and in which the Jews are the heroes. But maybe some latitude needs to be extended in the case of comic books and graphic novels, which often rely on conventional imagery.

The illustrations are wonderfully emotional and evocative. Pellejero often includes wordless panels—a method that recalls the silent movies that were roughly contemporaneous with the story—and these lend the story great power. Pellejero also drenches the book with color, as he explained in the same interview cited above:“In Malka . . . the color red has a huge importance for the dramatic scenes as the story develops, ochre for the soil of the Pampas and the Golem itself, green for the meadows and to create a certain feeling of joy, yellow for the moments when sickness takes hold of the characters, blue for the immense skies of the Pampas, the dream states, etc.” Viewed simply as a work of art, The Silence of Malka deserves a place on the shelves of graphic novel fans. Meanwhile, the golem himself—in this iteration so nearly human—lives on in all his haunting ambiguity.

Suggested Reading

The Rabbi Goes to Court

A new graphic novel of the Barcelona Disputation brings a famous medieval debate to life.

“In Order that They Didn’t Die Alone”: Remembering Claude Lanzmann

The iconic director of the most critically acclaimed movie about the Holocaust, Shoah, died last week.

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

Touch: Passover under COVID-19

It makes sense not to touch during a pandemic. But did we truly touch before it and will we after?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In