Jerusalem Reconstructed

After walking up and down Jaffa Road, Jerusalem’s main drag, for many years, Adina Hoffman began to muse not only about the street’s dilapidated condition but also about its relationship to “the multiple unrealized versions—and visions—of the city that exist and have existed in the minds of those who’ve felt compelled to try to build here, in all senses of that term.” Some of Jaffa Road’s decaying early 20th-century buildings particularly piqued her interest and induced her to embark on a journey she describes as an “excavation” of the buried past. In the course of her efforts to uncover the political, social, and cultural reality out of which these and other contemporary buildings emerged, she discovered three architects—a German Jew, an Englishman, and an Arab—who were not only superb professionals but also fascinating figures. Examining these men’s lives and careers, Hoffman has succeeded in evoking forgotten aspects of the period of the British Mandate in Palestine (1920–1948), a time when one could still dream of realizing the universal ideals that were associated with the “city of all cities.”

Erich Mendelsohn, to whom Hoffman devotes her first and longest chapter, had once been a famous architect in Weimar Germany and a key international figure in modernist architecture. The buildings he planned between the years 1921 and 1933, among them the department stores he designed for Salman Schocken and other Jewish tycoons, were considered milestones in Germany’s process of modernization. One of his last achievements in Germany was the “quietly spectacular waterfront villa” that he completed in 1930 “in a leafy Berlin suburb,” a gift for his wife Luise. There the Mendelsohns threw lavish dinner parties and musical evenings for Berlin’s cultural luminaries. At such events it was not uncommon for Albert Einstein to “arrive at their backyard in a sailboat, his violin tucked under one arm so that he could play trios with Luise and the acclaimed Hungarian concert pianist Lili Kraus.”

The rise of the Nazis brought an end to all of this. Always a man of foresight, Mendelsohn left Germany immediately after Hitler took over. He and Luise moved first to the Netherlands and then to London, where he opened an architecture practice and planned one of the first modernist buildings in England. While he visited Palestine many times, did a considerable amount of work there, and expressed great enthusiasm for what he described as the “true soil desired by my blood and my nature,” the Mendelsohns did not settle in Jerusalem until 1938. There they eventually made their home on the outskirts of Rehavia in an old flour mill with no running water and no fridge, living out the integration into the East in accordance with the “primitivist” ideal that had gained ground in European culture as an antidote to the “mechanistic” and “artificial” Western civilization. Luise designed the couple’s home in the local rural style and insisted on shopping in the markets of the Old City.

The flour mill soon became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings. Having developed a close relationship with Else Lasker-Schüler, the German expressionist poet who arrived in Jerusalem penniless and emotionally unstable, Luise took her under her wing, helped her secure a regular income, and arranged a number of readings for her, including one at the Schocken Library, designed by her husband. Hoffman’s description of this structure illustrates Erich Mendelsohn’s ability to create with minimal means a space that had a “spiritual” character—for the theatrical performance of a poet who had a hard time coping with the gap between spirit and matter.

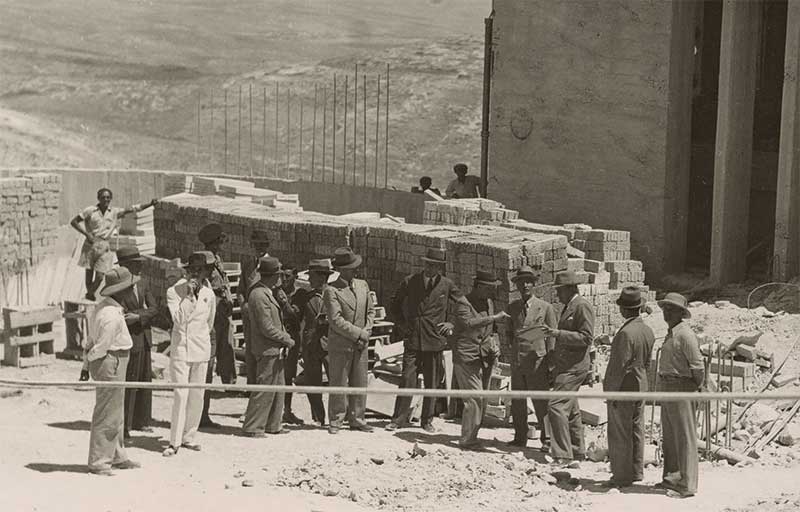

Mendelsohn designed not only a library for his former employer and fellow refugee, Salman Schocken, but a dazzlingly modern house, and took the lead in numerous other important projects, including Hadassah Mt. Scopus Hospital, the Anglo-Palestine Bank in Jerusalem, the private residence of Chaim Weizmann in Rehovot, and the Rambam Hospital in Haifa. Nevertheless, he remained frustrated. Even though in Germany, too—contrary to the impression Hoffman leaves—Mendelsohn’s glory days were in fact over by the latter half of the 1920s, he had still expected, as an important international architect, to become Palestine’s master builder. He had hoped, for example, to plan the Mt. Scopus campus of The Hebrew University. His disappointment over this and similar projects that failed to materialize, along with the fear of a possible German invasion of Palestine, prompted him to pack up once again and to leave with Luise for America in 1941. Even in the land of opportunity, however, Mendelsohn never regained the celebrity he had once enjoyed in Germany.

Hoffman’s brief biography of Mendelsohn tends at times to go into excessive detail with regard to such things as meetings of the Hadassah administration, with the aim of demonstrating the exhausting bureaucratic battles he was forced to wage in order to realize his ideas. Yet in her fragmentary style, Hoffman nonetheless succeeds in capturing the stormy nature of this architect who so well embodied the figure of the “genius-artist” adored by the heirs of German Romanticism.

An artist-architect, with both a cultural and a material vision, Mendelsohn knew how to read the language of a given place and to translate it into abstractions. The quality of his work is evident in the meticulous efforts to produce total designs in which every single detail carries meaning. Hoffman does not overlook the gap between Mendelsohn’s passionate “spiritual” pronouncements and his practical conduct, which was guided first and foremost by material interests. She also mentions some of the character traits—he was “stubborn, irascible, blisteringly honest”—that did not make his dealings with the local bureaucracy and indeed with potential clients any easier. Even with Salman Schocken, with whom he had a long-time and close relationship, Mendelsohn often engaged in fierce battles, despite the two men’s mutual admiration.

Yet Hoffman aims to do more than paint the portrait of a fascinating artist or describe the masterful buildings he left behind. For her, his stone buildings, which blended into Jerusalem’s mountainous landscape and translated the local organic rural building into a modern architecture, embody a world view that was brutally buried by the mainstream of the Israeli cultural and political elite associated with Tel Aviv. Like other Central European intellectuals who had settled in Jerusalem, including Gershom Scholem and Martin Buber, Mendelsohn believed in the possibility of combining the fulfillment of Zionism’s goals as a national movement with adherence to universal principles of justice and equality. Like them, he was heedful of the presence of another people in the land and believed that Zionism was primarily a spiritual revolution. His fascination with the rural Arab language of building, therefore, reflected more than an appreciation of the unique way in which the Arab homes were integrated with their natural environment and adapted to the area’s climate and topography. His turn to the local style of building for inspiration was designed to express, as he put it, Jewish integration in the Orient as a means of furthering the spiritual revival of the Semitic world. “The Jews,” he wrote, “seem to grasp the fact that Palestine can only be built up in close collaboration with the Arabs and that she can become a place of well-being only in case both peoples come to an understanding.”

Hoffman’s analysis of Mendelsohn’s world view, both as a modernist architect in the revolutionary early years of the 20th century and as a political and cultural figure in Mandate Palestine, leaves something to be desired. But with her strong gifts as a writer she is able to combine stray bits of information and personal impressions into a living, highly persuasive collage that reflects not only Mendelsohn’s personality but also everyday life in Palestine in the 1930s. She vividly illustrates the way in which the German-Jewish community of Jerusalem acclimated itself to life in a backwater Mediterranean town with accounts of such events as the Mendelsohns’ reception at their exotic home celebrating both the inauguration of the Hadassah hospital and the visit of an old friend, the exiled German conductor Hermann Scherchen, who had come to lead a series of concerts by the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. Her detailed descriptions of the building of Salman Schocken’s home and library illustrate not only Mendelsohn’s ability to create an extraordinary combination of East and West but also the difficulties involved in adjusting to a world in which such a feat could be only fitfully realized, a world which the architect eventually abandoned in disappointment.

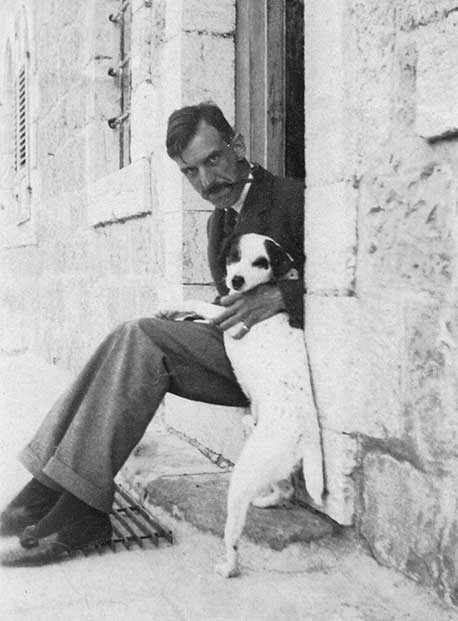

Austen St. Barbe Harrison left Palestine before Mendelsohn ever settled there. Between 1922 and 1937 he served as the British government’s chief architect in Palestine and planned some of the buildings that stand as impressive monuments to the British Mandate. Born to what he called “undistinguished British gentry,” he studied architecture in Canada and London, and then departed from his homeland, where “the sun does not always shine,” and spent the rest of his life in Mediterranean countries. Unlike Mendelsohn, the calm, reserved, and understated Englishman did not regard himself as a genius and objected to architectural theory, which he described as unnecessary “propaganda.” He avoided a flashy social life, preferring an “eremitical existence” in a small and modest home in the Arab neighborhood of Abu Tor, where he enjoyed breathtaking views of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Harrison planned most of the edifices constructed by the Mandate authorities in Palestine, including the Government Printing House, which displayed his mastery of the language of modernist minimalism. But his greatest contribution was expressed in three buildings in Jerusalem: the residence of the British High Commissioner (known as Government House), the Central Post Office Building on Jaffa Road, and the Rockefeller Museum. The museum represented, in his own eyes as well as those of others, the pinnacle of his work. If Mendelsohn, a faithful son of the modernist tradition, found in the local Arab architecture the authentic purity of a functional building attuned to the laws of nature and translatable into an abstract language, Harrison tried to create a synthesis between the various formal elements he discovered in his extensive travels throughout the Middle East. The museum, intended to hold and preserve the area’s archeological treasures, expressed the personality of a man who had fled modern Western culture and, in effect, made the East an ideal. “With its curved barbican and squat octagonal tower,” Hoffman writes,

its arrow-slit windows and wider, arched windows, its cave-like cloisters, sun-bleached courtyards, staggered rooftops, and multiple low-domed cubes, his design borrows elements from Islamic tombs and Crusader forts, Byzantine churches, Palestinian peasant houses, and even the Alhambra. In the process, it makes a mysterious if somehow inevitable whole of these disparate parts, both suggesting and transcending the cultural context of each squinch and every column.

Despite its large scale, its division into several different elements, and its problematic location near the walls of the Old City, the museum fit astonishingly well into its immediate environment.

Like Harrison, Spyro Houris, an Arab architect and a member of the Greek Orthodox Church, remained faithful to the eclectic tradition of the 19th century. The “wandering” Hoffman discovered the faded beauty of his picturesque buildings, adorned with colorful Armenian ceramic tiles, behind noisy and jumbled late additions and amidst the general grime and neglect of their immediate surroundings near Jerusalem’s central square. Despite her awareness that the architectural quality of Spyro’s work was not on a par with that of Mendelsohn’s and Harrison’s, Hoffman set out on a painstaking detective search for “Houris’s ghost” with the aim of rescuing it from oblivion. She soon found out that apart from his name, which remains engraved on his buildings, Houris left virtually no traces behind, nor had anyone ever seemed to bother to look for any. Even the few details she was finally able to dredge up with the help of archival staff and through conversations with descendants of the Greek Orthodox community still living in Israel were not enough to reconstruct the story of this mystery man. Nonetheless, these details, which include his hometown of Alexandria and the fact that he was president of the Jerusalem Lodge of the Freemasons, provide a new and interesting context for understanding his buildings, which for Hoffman represent the cosmopolitan Jerusalem of the Mandate era.

Since Houris’s main line of work was planning private residences “for those who stood at the top of the city’s social and economic ladder,” Hoffman’s research confronted her with a phenomenon that had been relegated to the margins of Israeli public consciousness: the existence of a multicultural elite in Jerusalem at a time when “one’s own identity could be multiple.” And in this respect, she argues, the eclectic nature of Houris’s buildings expressed the ethnic, religious, and national heterogeneity that characterized the Mandate-era city even as the political tension between Jews and Arabs and the violent eruptions on both sides consistently escalated over the years.

To the extent that Houris’s homes are discussed nowadays, they are taken purely as instances of an architectural style while the people who lived in them are now forgotten. They included, among others, such interesting characters as Khalil al-Sakakini, an intellectual of Greek origin who headed a Jerusalem literary circle and was an eloquent spokesperson for Arab-Christian nationalism. He publicly criticized the institution of the Orthodox Church and defined himself as a Palestinian patriot but also as “just one among humankind.” And there is the heartbreaking story of Is’af al-Nashashibi, a perfect representative of the Muslim intelligentsia whose majestic villa, built by Houris, held “one of the most important Palestinian archives anywhere,” which was lost when his home was looted by robbers after his death in early 1948.

Hoffman devotes considerable attention to the dramatic story of David (Tavit) Ohannessian, the Armenian artist who just barely escaped massacre at the hands of the Turks during World War I and established a ceramic workshop in Jerusalem. She relates how the flowered tiles painted by Armenian refugees and used by Houris to decorate many of his buildings eventually became one of Jerusalem’s most familiar visual symbols, common to all the communities that lived and continue to live in it.

Since Till We Have Built Jerusalem is not an academic study, as Hoffman herself emphasizes, one cannot fault her for the book’s failure to provide a broader historical background to her protagonists’ various world views. Yet it is worth noting, for instance, that the links she finds between Harrison and Mendelsohn are not coincidental, since both architects were associated with the philosophy of organic architecture whose central tenets promote a careful and harmonious integration of a building in its local context and the principle of total design. Relatedly, her critique of the architects of Tel Aviv’s White City is excessive, as is the contrast she creates between this group of architects and Mendelsohn. The “Tel Aviv architects” were not all of a piece, and several of them held views closer to Mendelsohn’s than she indicates. Finally, while Hoffman is aware of Mendelsohn’s personal weaknesses, she ignores problematic aspects of his world view as reflected in such texts as “Palestine and the World of Tomorrow,” where his views are uncomfortably close to the ideology of Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) and the principle of the decline of the West, both familiar from his homeland.

The book could have benefitted from tighter editing (sometimes the fragmentary style of the flâneur is distracting), and the illustrative photographs are not of the best quality, but Hoffman’s extraordinary ability to translate visual experiences into words and her powerful moral and aesthetic convictions shine through. Moreover, the book has practical ramifications. Hoffman rightly berates the Jerusalem municipal authorities for neglecting buildings that testify to an important historical period that they prefer to ignore; not only are Houris’s buildings gradually crumbling, Mendelsohn’s and Harrison’s masterpieces are threatened by ill-considered additions that will destroy them once and for all. If Hoffman’s book does anything to arrest these trends, it will not only have enlightened us about the past but will have performed a great service for the future of Jerusalem.

Suggested Reading

Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

The exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks on Jewish power and politics is illuminated by the history of Hanukkah.

As Though the Power of Speech Were an Ordinary Matter

Moods provides glimpses into Yoel Hoffmann’s life in literature and his ambivalence about the project of capturing life in words.

It’s Spring Again

A startling painting on the walls of the ancient synagogue at Dura Europos depicts some 2nd-century Jews who have, until recently, been dead and who look very surprised to have been reconstituted and revived.

Looking Backward and Forward

Response #2: David Biale revisits his provocative 1998 essay on Jewish assimilation.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In