Poisoned Gefilte Fish, Broken Heart

In his introduction to The Birobidzhan Affair: A Yiddish Writer in Siberia, the translation of Yiddish poet Israel Emiot’s harrowing prison memoirs, Michael Stanislawski wrote that its “true, if unstated, subject . . . is the tragedy of modern Jews’ nearly boundless capacity for self-delusion.” Emiot had been among those who allowed themselves to believe in the project to create a Jewish state in the Soviet Union and were cruelly fooled not once but twice by Stalin. The well-known contemporary saying notwithstanding, it would be unfair to shame them for their gullibility. After all, by the time Emiot and his fellow Yiddish writers in Birobidzhan were about to be sent to the Siberian Gulag in 1948, self-delusion—that is to say, hope—had become the only alternative to despair and madness.

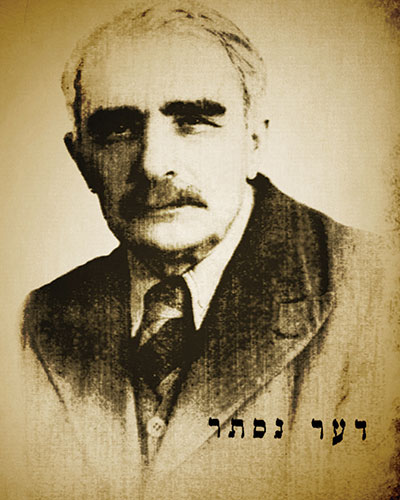

The Soviets’ initial promise, in 1928, of some form of Jewish autonomy in an isolated, forbidding, eastern corner of the republic, bordering on Japanese-occupied Manchuria, ignited the first flowering of hope in Soviet Jewish national autonomy. This hope was crushed by Stalin’s Great Purges less than a decade later, by the end of which there remained almost nothing distinctively Jewish about the farcical “Jewish Autonomous Region.” Already well before the purges, more than half of the original Jewish settlers had long abandoned Birobidzhan and returned to their homes, in Moscow and Minsk, and—incredibly—Los Angeles, New York, Montreal, Buenos Aires, Haifa, and Tel Aviv. The intense, much briefer revival of the initiative after the Holocaust lasted less than two years, culminating in the show trials of Jewish literary, cultural, and political leaders, Emiot and his friend the great novelist known as Der Nister among them, and their exile to the Siberian Gulag.

Reality never discouraged pro-Birobidzhan Jewish organizations in America and Canada, such as IKOR (the Organization for Jewish Colonization in Russia) and Ambidjan, which continued to publish propaganda about Birobidzhan, in Yiddish and English respectively, through the mid-1950s. The New York Communist Yiddish daily Morgen Freiheit not only failed to report on the many disastrous crop failures, floods, and famines in, and evacuations of, Birobidzhan; it suppressed any news of Stalin’s brutal purges until after his death.

In 1947, the Kremlin had officially “unfrozen” the Birobidzhan initiative. This resulted in the stunningly fast displacement of more than ten thousand Jews from their prewar homes, mostly in Ukraine, via a series of 11 long Pullman freight trains (eshelonen, in Yiddish), each typically carrying more than one thousand Holocaust survivors on almost month-long treks to an alien region well over four thousand miles from their prewar homes. While the destination’s isolation, primitiveness, and huge distance from these Jews’ places of origin were always obstacles to the success of the Birobidzhan project, the idea of living so far from the former Pale of Settlement also offered these Ukrainian pogrom and Holocaust survivors an alluring, if ultimately illusory, sense of security.

As the Yiddish poet Yosef Kerler, who was among the Jews who departed Vinnytsia, Ukraine, on the tsveyter (second) eshelon to Birobidzhan on June 6, 1947, observed, they had:

a vague, stubborn dream—to be as far away as possible from “home,” where the ground was drenched in Jewish blood, to be as far away from the non-Jewish neighbors, who either gave a hand to the terrible slaughter of the Jews, or merely plundered Jewish property, or outwardly appeared compassionate while in reality furtively rejoicing. To be free from the eternal hatred. To be among [our] fellow Jews [tsvishn undzere].

In short, they dreamed of a land, or at least a territory, perhaps a Soviet state, of their own.

Israel Emiot had been living in Birobidzhan since 1944 as one of its few distinguished intellectuals. His literary loneliness was briefly alleviated when that second eshelon pulled into the world’s only train station whose name was—and remains today—boldly carved in granite Yiddish letters. For on that second transport was not only his fellow poet Kerler but the older and more illustrious writer Pinkhes Kahanovitsh, known by his pen name Der Nister(The Hidden One), as well as journalist Ilya Lumkis, the Birobidzhan “bureau chief” (and sole correspondent) for the Moscow Bolshevist Yiddish newspaper Eynikayt.

The four writers quickly became close collaborators who tirelessly promoted the establishment of Yiddish schools, adult Yiddish language classes, Yiddish literary soirées, the expansion of the repertoire of the BirobidzhanYiddish State Theater, significant additions to the Yiddish—and even Hebrew—holdings of the Sholem Aleichem Library, and so forth. Emiot and Der Nister had a special bond, as—in contrast to almost all the other artists who had ever come to Birobidzhan, along with the majority of Yiddish writers across the Soviet Union—they shared profoundly religious upbringings and advanced, one might say higher, Jewish educations. Emiot was one of Der Nister’s very few readers who caught his every allusion to biblical, rabbinical, and kabbalistic texts and understood the deep Hasidic resonance of his chosen pen name, an allusion to the period of self-seclusion before a tzaddik revealed himself.

Der Nister was born and raised in Berditchev, where he had been steeped in the world of Hasidism. Unlike many of his colleagues who had left the world of tradition, he never stopped studying Kabbalah and the teachings and stories of the great Hasidic masters, Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav in particular (his brother became a Bratslaver Hasid), as his great unfinished novel The Family Mashber testifies. Emiot, for his part, was raised in a pious Polish Jewish family and had been ordained at the fabled Yeshivat Hakhmei Lublin. Moreover, Emiot was a proud descendent of the great Polish Hasidic master Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak (The Holy Jew) of Przysucha—follower of the great Khoyze, or Seer, of Lublin.

During their brief time together in Birobidzhan, Der Nister told Emiot an odd, haunting story about his holy ancestor and his teacher, the Seer.

Rabbi Yaakov Yitzhak of Przyscha was among the guests at the Passover seder of his teacher, the famous “Seer of Lublin.” The latter sat at the table and read . . . with his head and body wrapped in a talis (“prayer shawl”). At the words, “uvemorah gadol: zeh gilui shekhinah” (“and with great terribleness—this refers to the revelation of the Divine Presence”), he removed his talis to reveal his face. When this happened, from fear and dread of the Almighty . . . Rabbi Yaakov Yitzhak of Przyscha lost all his teeth, except one . . . he. . . would call this tooth roshe “the evil one”—because it did not fall out at the words of his teacher: “and with great terribleness.”

As Ber Kotlerman deftly notes in his important new monograph on Der Nister’s fateful trip to Birobidzhan, Broken Heart/Broken Wholeness, he used this tale to dramatize the need for Jewish writers to be willing to sacrifice themselves for Yiddishkeit. As he put it, “Ot dos kharakterizirt di groyse, gute yidn”—this, the willingness to “fall out,” or die, characterizes the great and good (Hasidic) Jews. As for Kerler, despite his more secular upbringing, he fully shared these two colleagues’ passion for Yiddishizing Birobidzhan, as well as a healthy, if carefully concealed, skepticism about Bolshevik rhetoric and enforced Soviet cultural and literary norms. All three were fearlessly dedicated to creating a meaningfully Jewish, which is to say Yiddish, homeland in Birobidzhan.

Kotlerman’s book not only vividly recounts Der Nister’s experiences in Birobidzhan but also provides the first English translations of the powerful, moving essays he composed while travelling on the eshelon from Vinnytsia, as well as a substantial excerpt from the hitherto unexamined six thick volumes of Russian transcripts of the subsequent trumped-up “Birobidzhan Affair,” in which Der Nister, Emiot, Kerler, and others were accused of being Jewish conspirators.

In an appendix, Kotlerman also reproduces photo images of the very last writings that have survived from Der Nister’s hand, his Birobidzhan manifesto, which have never before been seen by scholars,along with a brief, trenchant explication of that barely readable manuscript. The manifesto, which may have begun as notes for lectures, reveals the inner sentiments of a singularly important Yiddish writer during the final year of his life while confined to a Siberian camp for the crime of having taken the promise of a Jewish Autonomous Region seriously:

. . . the main condition for a people to be considered as such is, first of all, soil, a place

. . . where all the forces and abilities given to it should find their fullest expression, sovereignly, without hindrances . . . Is it necessary to say here that we are talking about the Jewish Autonomous Region, which could, today or tomorrow, with our good will, turn into a [Soviet] republic, the seventeenth, in addition to the sixteen that already exist?

In a characteristic turn of phrase, Der Nister wrote that the realization of this possibility would be a “brokhe af doyres” (blessing for future generations). The bitter irony is almost unbearable.

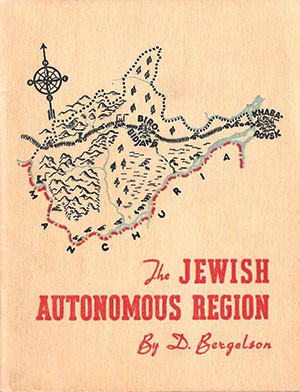

The idea of resettling Russia’s Jews, who had been concentrated in the former Pale of Settlement and most of whom were merchants and craftsmen, was originally propelled by two priorities of the young Soviet State: namely to decisively shape the national, cultural, and linguistic development of its large national minorities and to transform the Jews from the merchant class to a “useful and productive” agricultural one.

The Jews had a distinct language and culture, to say nothing of their rich Yiddish and Hebrew literatures. What they lacked was an identifiable Jewish land. The attempted mass transition of the Jews from the merchant class to being “productive” agrarian citizens of the USSR had resulted in the creation of more than a score of Jewish agricultural settlements in the early 1920s, mostly in Crimea. In 1928, the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union designated an area in the easternmost region of the Soviet Union, roughly the size of the state of Vermont, as a Jewish agricultural colony, which would eventually be called Birobidzhan. The initial objective was to rapidly resettle at least 50,000 Jews there as “useful and productive” citizens within Stalin’s “multiethnic” republic.

This original goal of agricultural resettlement quickly yielded to the forbidding realities of the region and the gradual industrialization of Birobidzhan. Quasi-nationalistic ideals of a distinctly Jewish homeland, a cultural center with Yiddish as its official language, became increasingly more of a priority than farming. In 1934, the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party upgraded Birobidzhan’s status to that of a Soviet Jewish Autonomous Region. The problem was that among the USSR’s almost four million Jews, the Jewish population of this autonomous region never exceeded 18,000, less than one-tenth of a percent of Soviet Jewry and less than 10 percent of the general population of the region.

The single most distinguished Yiddish writer who advocated for a Soviet Jewish cultural, but not nationalist, home during this period of the “first aliyah” (if I may) was David Bergelson. After a brief visit to New York, he had concluded that America’s Jews were doomed to total assimilation. As for the Jews in Palestine, Bergelson described them vividly, if unoriginally, as “dancing on a volcano,” after the murderous Arab riots of 1929. Bergelson visited Birobidzhan briefly in 1932. Although he never returned, he became one of its most influential enthusiasts, writing ecstatically about the hypnotizing effects of the deep blue northern skies, beautifully rugged mountain ranges, and seemingly endless vistas of her plains. What he chose not to do was look down to notice the deep muds that remained after the savage winters, the brutally humid summers, or the alternating floods and droughts which doomed the hard work of the idealistic Jewish farmers on Birobidzhan’s kolkhozs, or collective farms. This was the poison literary fruit of either shameless propagandizing or fear of execution. Bergelson went so far as to extol, of all things, the exceptionally hot and healthy sun in Birobidzhan, which, he claimed, was “three times as powerful as the sun in Berdichev, Minsk, or Kiev,” and absurdly to proclaim that, “This sun, coupled with the sun of the socialist homeland, makes the Jewish people healthy and strong.” This was precisely the kind of craven, self-shaming, and farcical Yiddish verse that the Soviets long and happily exploited. One of the greatest writers in Yiddish literary history had tragically become one of Stalin’s most useful of Jewish idiots. He published two “manifestos” proclaiming his loyalty to Birobidzhan, which he extolled as a “gift from Stalin, the Jews’ best friend.”

The reality of Birobidzhan was bleak. The first colonies of idealistic settlers to work its forbidding land soon faced a disastrous summer, marked by floods that wiped out all of the work of the previous eight months, followed by a terrible winter which brought them near starvation, surrounded only by forests where wolves, tigers, and bears roamed. In 1934, just as the remnant of Jewish farmers on kolkhozs such as Birofeld, Valdheim, Amurzet, and IKOR (after the North American organization that funded it) were getting back on their feet, summer brought unbearably humid heatwaves followed by more catastrophic floods and both human and bovine epidemics. The idealistic settlers, especially those from Canada, the United States, and Argentina, who had not yet abandoned Birobidzhan began to flee after the ensuing crop failure and the deaths of most of the livestock.

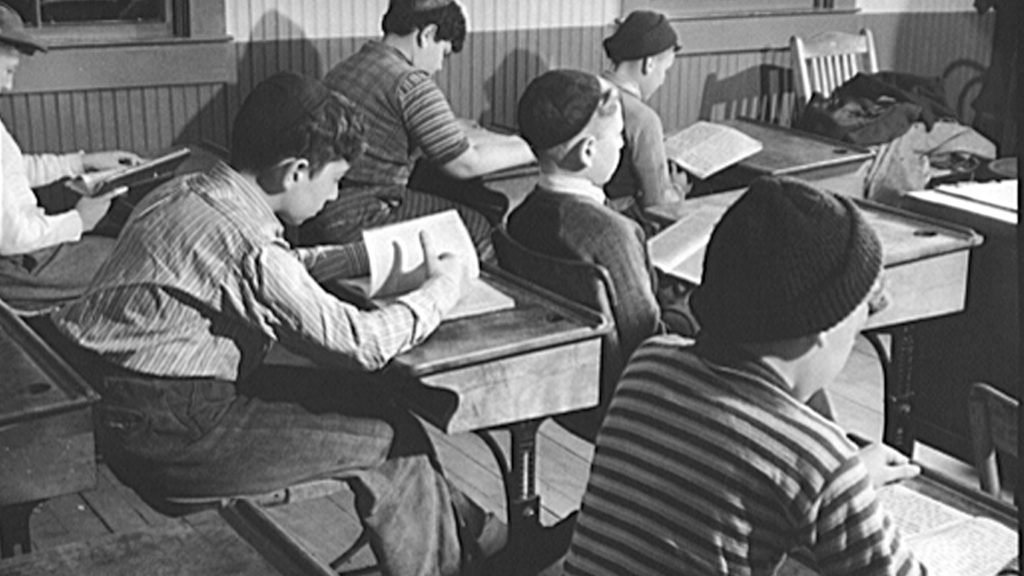

And yet, despite the many obstacles, by the mid-1930s important educational and cultural institutions had been established in Birobidzhan, including a network of Yiddish schools, the Sholem Aleichem Yiddish Library, the Yiddish State Theater, and a Yiddish daily paper, the Birobidzhaner shtern. The very height of optimism among the Jewish settlers who soldiered on came in February 1936, with the visit of the most powerful Jew in the Soviet Union, Stalin’s closest political ally and trusted friend Lazar Kaganovich, secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Kaganovich delivered long lectures about Leninism to local members of the party, attended a gala performance at theBirobidzhan Yiddish State Theater,which was subsequently named for him, and publicly proclaimed that the time had arrived to perform “heroic epics in the history of the Jewish people” on its stage.

A highlight of Kaganovich’s visit was the dinner he had at the home of the local chairman of the Communist Party Matvei Khavkin. Khavkin’s wife Sofia prepared an array of traditional Jewish foods that were becoming increasingly rare in Soviet Russia, including kreplach and gefilte fish, which Kaganovich praised highly. And yet, Khavkin himself was soon arrested and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in the Gulag for his alleged crimes of Trotskyism and bourgeois nationalism. In an ultimately cruel irony, his wife Sofia was arrested and sentenced to hard labor in Kazakhstan, for the alleged plot to assassinate Kaganovich by serving him a poisoned portion of gefilte fish at the dinner which had elicited such high praise from its supposed target. By the fall of 1937, almost nothing of the original idea of creating a Soviet Jewish state in Birobidzhan remained: The migrations ended, the Yiddish schools and publications ceased, and the Jewish population froze at about 15,000. Few local Jewish leaders escaped Siberian imprisonment or execution.

The brutally sudden and tragic purge of the now-farcical Jewish Autonomous Region was particularly painful to the Soviet Union’s Yiddish artistic and literary elite, members of the Jewish Antifascist Committee (JAFC), so many of whom had trumpeted their great hopes for its future. Throughout the 1930s and early 1940s there really was only one great Soviet Jewish writer who neither praised nor ever mentioned the Jewish Autonomous Region, Der Nister. Known for his political caution and his literary art of concealment, Der Nister shared neither the cravenness nor cowardice that were tragically on display in the show trials and executions, culminating in August 1952 with the executions of all the remaining members of the JAFC. And yet, in the bitterest of ironies, Der Nisterhad been arrested well before the massive sweeps of 1949, precisely for his late-life enthusiasm for the revival of the frozen Birobidzhan project and his fearless insistence on turning it into one of the two Jewish national centers that would realize his ideal for a post-Holocaust reconstruction of the “broken wholeness” of his people, as he put it, “ours over here, and theirs over there.” There, meaning the young State of Israel.

Kotlerman has translated the emotional essays Der Nister wrote on the train to Birobidzhan. His depictions of a wide array of characters, from child survivors to young soldiers just recently discharged from the Red Army, are exceptionally powerful. Seeing this mass of Jews, “the nation that survived the sword,” huddled together on a four-thousand-mile ride to an entirely unknown new home fills him with national and religious fervor. He comments on all of the Yiddish subdialects heard on the train, “Volhynian, Crimean, Odessan and mainly Podolian,” and imagines the eshelon as a modern-day Noah’s Ark, sent to rescue and repair the broken Jewish nation.

In these impressionistic essays, Der Nister employs a doppelganger, a kind of consoling angel or shadow, whom Der Nister calls “My Jew” and who appears to him whenever he begins to doubt the future in Birobidzhan. Thus, when he imagines this long journey as just more wandering, another exile, “the nation again on the way . . . Starting at the Nile, through all the world’s waters, and now even up to the Amur . . . ” his shadow rebukes him:

No, it’s not similar . . . The present wandering is not at all like all those earlier ones . . . A deep break is occurring in the psychology of the Jewish masses, for the sake of reconstruction, in order to repair the broken wholeness, and put an end to the historical silliness that always left them hanging in the air . . . After the recent Catastrophe came the fundamental reexamination. In the Middle Ages, such events, which occurred far and wide in the Diaspora, would awaken hopes in false messiahs. Now—we see a striving for a real action . . . an awakening . . . and not only will there be no obstacles, but rather maximum help and support [from the Soviet state].

Der Nister’s cautious optimism during his trek to Birobidzhan was most movingly made manifest in his response to a dramatic wedding that took place on the trip. A Jewish soldier who had lost his entire family married a girl who had somehow survived when her entire family had been shot by the Nazis. While Der Nister was too ill to attend the wedding, he describes how the bride came to him before the chuppah and requested his blessing, as if he himself were a Hasidic rebbe. Having heard her heartbreaking tale of loss and survival, Der Nister observes that the bride had shed one single tear, about which he muses: “In truth, if we are dealing with crying, the bride should have been betrothed to the sea, in order to shed the necessary amount of tears.”

Finally, Der Nister intones, “ve-yibone beys be-Yisroel” based on the standard rabbinic blessing under the chuppah, that the newlyweds might together build a faithful home in the midst of the Jewish people. Here Kotlerman makes a slight error in correlating this blessing with the prayer for the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, which became a popular folk song, “she-yibone beys ha-mikdash,” which, while employing analogous language, has nothing to do with Jewish newlyweds and their future home. In so doing, he unwittingly overstates the extent of Der Nister’s messianic and pseudo-Zionist enthusiasm, which was limited to his great hopes for a fundamental change in Jewish history that would be achieved by the success of the Soviet Jewish Autonomous Region. In a terrible irony, this same “Zionist-messianic” misreading of Der Nister’s blessing was contained, along with a Russian translation of hissecond essay, in a report making the case for the arrests and show trials in Khabarovsk. The document, which would be Der Nister’s death warrant, was seen sitting on Joseph Stalin’s desk in early 1948!

Kotlerman’s very minor error in no way diminishes the general accuracy of his interpretation of Der Nister’s thinking in 1947. He clearly demonstrates that Der Nister went from being a reclusive, secretive symbolist who kept as far from politics as he could to being a fearless champion of Soviet Jewish nationalism, while taking on an increasingly public role as a kind of secular tzaddik, who blesses, consoles, and advises all who come to him for counsel.

In his analysis of a stunning 1944 article titled “Hate,” published by Der Nister just three years before he boarded the second eshelon, Kotlerman shows the early signs that he had taken on this role of a modern-day comforter, echoing the powerful chapters of comfort of Jeremiah after the destruction of the First Jerusalem Temple:

. . . you [must] feel and [be] certain that, no—the last line of our life-account has not yet been drawn. Our spring has not yet dried up, and these previously abandoned, talented children whom we know, and those we don’t know,—children . . . are our comfort, our promise and guarantee of our future rebuilding and renaissance . . .” Woe to the Hitlers—those that have disappeared, those that still exist, and those that may possibly rise in the future. Amen, woe to them . . .

I cannot think of another secular Soviet Yiddish writer who concluded his thoughts with a pious “Amen.” Kotlerman is emphatic about Der Nister’s self-assumed role as a secular Hasidic tzaddik. He bases this claim not only on evidence from the writer’s own Holocaust-era works, and the two essays presented in the book, but also on the impressions in the memoirs of his two close collaborators, Emiot and Kerler. Emiot depicts Der Nister as being completely preoccupied with Kabbalah, reciting long passages of the Zohar from memory. Emiot claims that he had also memorized the teachings of Nachman of Bratslav’s Likutei Moharan.

The title of Kotlerman’s third chapter, “A Man Dieth in a Tent,” is based on Der Nister’s application of Rabbi Nachman’s interpretation of a verse in the Torah, which was read during the week of his arrival in Birobidzhan, to Yiddish writers and Russian Jewish leaders. The plain sense of verse describes the spread of impurity from contact with a corpse: “If a man should die in a tent, all that is in that tent shall be impure for seven days.” Rabbi Nachman reads the verse this way: “If [one is to be] a man [he must be willing to] die in the tent—namely the tent of Torah.”

“They [the righteous men]” Der Nister said, “did not play around with their Yiddishkeit; at any moment they were ready to sacrifice themselves.” Kotlerman quotes Der Nister’s bitter letter to Nachman Mayzel in New York about the nishtike rol (pathetic role) of his “colleagues” on the JAFC who continued to do Stalin’s bidding to the end. Their failure was on account of their “connivance, pessimism, cowardice, and reconciliation withtheir own nothingness” (in Yiddish, more powerfully: sholem-makhn mit der eygener nishtikayt).

Having finally gotten on board (literally!) the Birobidzhan enterprise, it was his inspiring encounters with children and adolescent survivors that bolstered Der Nister’s hopes for the future of Soviet Jewry. Seeing these tough, determined young survivors, he asks, “what kind of building in the world can resist being built by such types?” He anoints the youngest children on the train as “little Davids against whom no Goliath will ever prevail.” Reading of this confidence in Jewish national continuity that these Holocaust orphans inspired in Der Nister reminded me of the most powerful and, I believe, personal of his 1943–1944 short stories, “Vidervuks,” or Regrowth, the title of a recent English translation of his Holocaust-era stories.

In his introduction, Kotlerman recalls his promise to Der Nister’s eminent Hebrew translator Shalom Luria that he would follow his advice and “look the artist straight in his face.” The face Kotlerman sees, and compels us to see, is as awe inspiring as that of the Khoyze, the Seer of Lublin.

Der Nister was reported to have died in a Soviet prison camp, somewhere on the edge of the Arctic Circle in 1950. David Bergelson and others who had cravenly made peace with “their own nothingness” were executed two years later in the “Night of the Murdered Poets.”

Suggested Reading

“We Found Our Outrage”

On March 2, 2015, a handful of campus activists announced that Andrew Pessin was an anti-Palestinian bigot. “I feel unsafe,” wrote Lamiya Khandaker, the student chair of diversity and equity at Connecticut College.

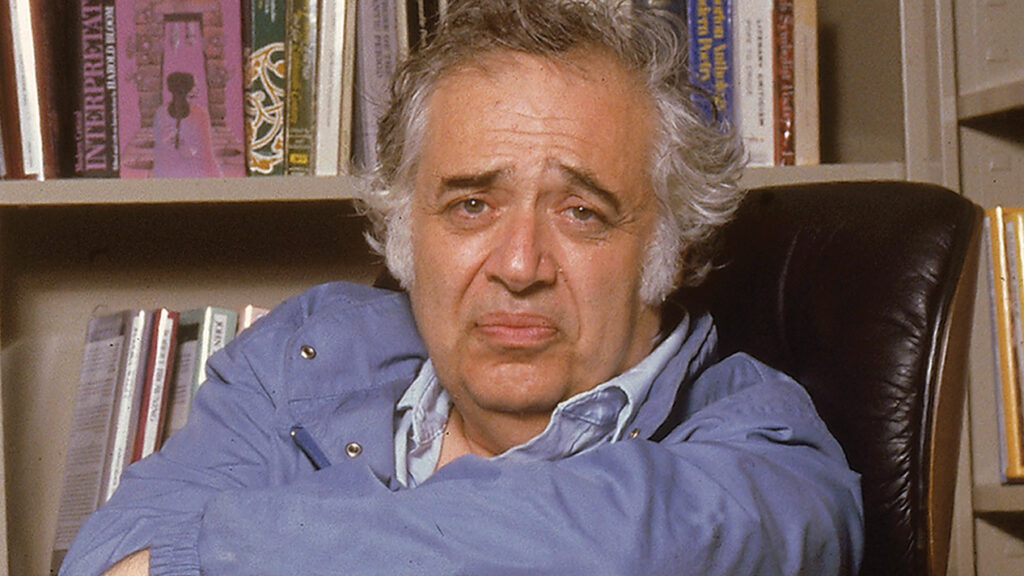

Remembering Harold Bloom

As Harold Bloom's student, I wanted to be transported to the heights of the literary sublime where he always seemed to reside, whatever the cost (it seemed considerable).

The Day School Tuition Crisis: A Short History

In 1935, Israel Chipkin wrote that day schools were “financially prohibitive” for most Jews. The more things change . . .

The Rebbe and the Professor

After the war, the great Jewish historian Salo Baron wrote to Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, for help with his work on the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction. As Hannah Arendt suggested in a side note to Baron, the commission probably wasn't “kosher” enough for Schneersohn, but their exchange illuminates a dark historical moment.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In