Remembering Harold Bloom

Inevitably, at some point in every semester, I share with my students my impersonation of Harold Bloom. Face buried in one trembling hand (the other holds open a book), I shut my eyes in great long blinks, between which I stare wide-eyed at the air in front of me. “I reread this passage this morning,” I say, or as best I can, incant, pausing almost between each word, “and it . . . wounded me. Why?”

My performance has become exaggerated over the years, but it conveys something of the impact of Bloom’s classroom presence on me and generations of his students. We were at first amused and finally devastated by the urgency, the veritable spiritual crisis, that attended his encounter with the passages of poetry and prose that he loved. He grappled with them like Jacob wrestling with the angel. Whatever the cost (it seemed considerable), we wished to be transported to the heights of the literary sublime where he always seemed to reside. And so we went back to our rooms and returned to the texts, whether Shakespeare or the Bible, Whitman or Kafka, Freud or Wallace Stevens. We read them again and again—this time with feeling, as the bandleader says—hoping to see for ourselves what had moved this most prodigious embodiment of literary insight to plead for our (alas) inadequate assistance. We wanted to be wounded.

No brief overview could do justice to Bloom’s literary career. The sheer heft of his output is overwhelming. He published more than 40 books of his own prose (his last is still forthcoming), and his uncollected introductions and stray essays would fill another dozen volumes, at least. He wrote about seemingly every well-known literary author, and many lesser-known figures, from Homer to the present. No literary critic in the English language was as prolific or covered as much ground as Bloom.

He began his career as a scholar of English Romantic poetry at a time when, in academic circles, T. S. Eliot held the keys to the literary kingdom. (A framed photograph of Eliot hung, Bloom would recall, on the wall of the English department at Yale when he was a graduate student.) Bloom’s dissertation book, Shelley’s Mythmaking (1959), defended the reputation of the poet that Eliot had worked hardest to diminish, and began, moreover, by quoting a lengthy passage from Martin Buber. It is hard to imagine anything more antithetical to Eliot’s Anglo-Catholic, anti-Romantic bias. Bloom’s next two books—The Visionary Company: A Reading of English Romantic Poetry (1961) and Blake’s Apocalypse (1963)—were also lucid and permanently useful commentaries insisting on the aesthetic value and intellectual coherence of Romantic literature. But even in these early works, he comes across as something more than an academic critic. For Bloom, who had been raised as an Orthodox Jew, Romantic poetry constituted a secular scripture. As Paul Cantor recently put it: “Blake’s prophecies became his Torah and, like a Talmudic scholar, he painstakingly commented on the profound questions they raised.”

The second phase of Bloom’s career was inaugurated by The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (1973), his breakaway book. I remember taking down the slim black paperback edition from the shelf of my local bookstore in the fall of my senior year of high school. I had been introduced to some literary criticism already, but nothing like this. Was it criticism? I felt as if I had been dropped into a cosmic, apocalyptic Western. The terminology was thrilling and baffling, like weaponry forged on another planet. But the central argument could not have been clearer. We had arrived too late, “after the flood.” The radiance of the literary tradition was overwhelming, paralyzing. Only the strongest of the strong had a chance of literary survival. Weaker talents succumb to influence. Strong poets struggle against it, distorting and repressing their literary inheritance in order to make room for themselves. Whatever else he was doing, Bloom was also narrating his effort to break out of the confines of his earlier scholarship. The Anxiety of Influence wasn’t a commentary on Romantic poetry; it was an act of Romantic mythmaking. As if to drive the point home, Bloom appended a prose poem of his own composition as his epilogue.

The 1970s was the decade of the French Invasion in literary studies in American universities, and Bloom became associated, in the minds of many, with the Yale school of criticism, a group of critics influenced by deconstruction. But although he was friends and colleagues with its founding figures, his work had little in common with theirs. His obsessive interest was literary strength: What made one poem greater than another? How had the strongest literary artists managed to revise the tradition they inherited? What made a poem canonical?

Starting with his 1975 book Kabbalah and Criticism, he turned increasingly to Gershom Scholem’s account of the Jewish mystical tradition for his theoretical models. Kabbalah, he argued, offered not only a “direct portrayal of the mind-in-creation” but also “a model for the processes of poetic influence, and maps for the problematic pathways of interpretation.” Bloom went on, of course, to write extensively on religion and religious texts. Most famously and outrageously, in The Book of J (1990), he speculated that the primary author of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible was a woman, “either a princess of the Davidic royal house or else the daughter or wife of a court personage,” with a genius for literary irony. It is tempting to say that, having treated the literature of English Romanticism as his Torah, Bloom now treated the Torah as literature and Kabbalah as literary criticism. But for Bloom, the distinction between sacred and secular texts had no meaning.

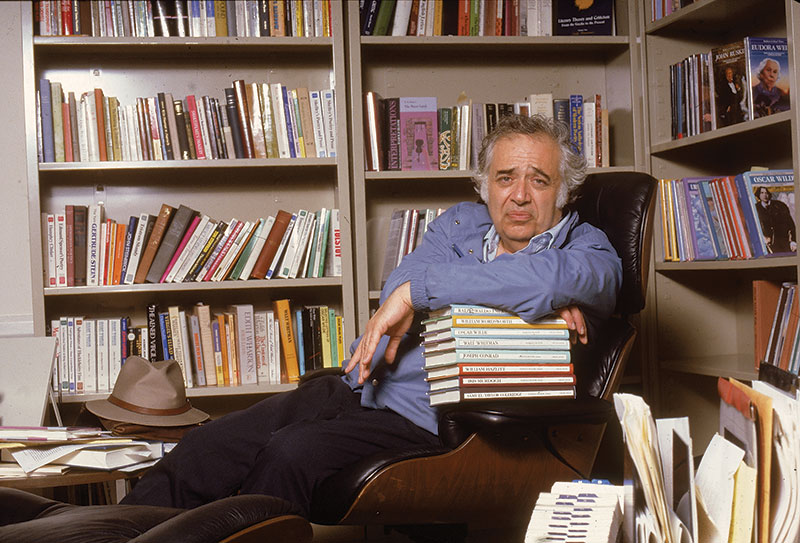

In the 1980s, when I was his student, Bloom was in the midst of remaking himself into a critic for the common reader. It was a transformation that began with a flurry of entrepreneurial activity. In my final year at Yale, I started working at “the factory,” as Bloom called it: a branch of Chelsea House Publishers that had opened in New Haven, employing at its peak 16 full-time staffers and a small army of Yale graduate students as research assistants. The goal was to replace the popular Prentice Hall series Twentieth-Century Views, editions of modern essays on major literary authors (and works) that could be found in both college and high-school libraries. The difference was Bloom. Twentieth-Century Views had employed a different editor—an expert on the subject—to introduce each volume. At “the factory,” we assembled bibliographies and (with Bloom’s final approval and occasional tweaking) tables of contents for what would amount to over six hundred volumes, every one of them introduced by Bloom. He had always been prolific, but now he was writing at an uncanny pace. He frequently referred to his need to provide lifelong support for a disabled son as his primary motive, but he also seemed to revel in his new role. Who else could have played it? Who else could claim to read four hundred pages an hour with retention? Who else had something to say about every writer in the Western literary tradition from Homer to Philip Roth? What other literary critic had that kind of strength? “I am writing an introduction a day!” he trilled, not a little astonished at himself.

At “the factory,” Bloom was an expansive and jovial presence. He frequently held forth, playing to the crowd, or perhaps playing primarily to himself, but we all stopped to listen. Advised by his doctor to lose weight, he seemed always to be holding a can of Diet Coke in his hand. He would wave it aloft and ask, “Have you observed that the Bloom is vanishing?” His rants against deconstructive critics were particularly exuberant performances. “When I read their discussion of a poem, I feel as if I were reading an account of a great swimming competition, in which the author reported only on the temperature of the water. . . . Language is their demiurge. . . . In the end, the only theory is oneself, and one is idiosyncratic.”

In retrospect, Bloom was warming up for his role as the defender of the literary canon. Within the academy, the very idea of literary value had come under suspicion. The “great books” were increasingly described by scholars as products of their historical moment, no different in kind from other anthropological artifacts. Many went farther, regarding them as cultural propaganda, monuments to a history of social and political oppression. Having spent a decade plumbing the mysteries of literary strength, Bloom now sought to defend it against its detractors. In his bestseller The Western Canon (1994), he unabashedly celebrated the literary originality of 26 of the world’s most famous writers, lashing out against what he called “the School of Resentment.”

One afternoon, a story was making the rounds at “the factory” that had everyone amused. Bloom had been interviewing an applicant for an editorial position. At one point, she expressed anxiety about the longevity of the Chelsea House project: She wasn’t looking for a temporary job. Bloom assured her that she had nothing to worry about: He had been told by a fortune-teller that he would live until 103 years of age. As the years ticked by and Bloom continued to teach and publish into his late eighties, I began to take the fortune-teller’s prophecy for granted. He seemed unstoppable, and indeed he was, until the end. He taught his last class four days before his death, at the age of 89, and published nine books in his final decade, six of them in the last three years of his life. After a fall robbed him of his power to write longhand, as was his custom, he turned to dictation—“which I still find strange. Yet the power to go on exploring literature remains strong.”

I saw Bloom for the last time in the spring of 1998. I was finishing my dissertation at the University of Virginia when he came to lecture on King Lear. (His great tome Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human would appear later that year.) Onstage, he seemed in pain, repeatedly begging our forgiveness for “this grotesquery,” by which he meant the frequent flapping of his left arm like a broken wing. Time had not been kind to his shoulder, he explained. All of it strangely abetted his talk, which was darkly magnificent. He was becoming Lear, or so it seemed, consumed by his own, and his subject’s, Jobian afflictions. But at the reception after the lecture, he was all smiles, babbling at great length with the infant child of a former student. At dinner at a restaurant later that evening, he seemed as light-hearted and affable as Falstaff, ordering several bottles of wine for our table (“This one is going to be a real treat for you!”) and holding forth, incessantly, with humorous stories about writers he knew or had known.

That Bloom could be Lear in the afternoon and Falstaff in the evening will surprise no one who has spent time in his presence. Oscillating between melancholy and glee, but displaying both moods with theatrical exuberance, he had always been, from the moment I encountered him, both a literary critic and a literary character. Literature had created him. He was a creature of it. And he created himself through it. In this regard, among others, he resembled his hero, Samuel Johnson. Over the years, and particularly in the weeks since his death, I’ve found myself exchanging stories and anecdotes with friends and colleagues who studied with Bloom or came in contact with him at one time or another. He made Boswells of us all.

But in the end, he became his own Boswell. Bloom was fond of quoting Oscar Wilde’s statement that criticism is “the only civilized form of autobiography,” dealing, as it does, “not with the events, but with the thoughts of one’s life.” He used it again as his epigraph to Possessed by Memory (2019), his most recent book and the last to be published in his lifetime. By Wilde’s definition, of course, all of Bloom’s criticism is autobiographical. But Possessed by Memory pushes the genre of literary criticism to its autobiographical limit and beyond, shuttling between memoir and exegesis. It is a mode that comes naturally to Bloom: He had been inching toward it for years.

In one of the book’s most poignant passages, from a chapter titled “More Life: The Blessing Given by Literature,” he is flooded by childhood memories of his mother:

Last night, in the small hours, an image of my mother came back to me. Vividly I saw myself, a boy of three, playing on the kitchen floor, alone with her as she prepared the Sabbath meal. She had been born in a Jewish village on the outskirts of Brest Litovsk and remained faithful to her traditions. I was the youngest of her five children, and I was happiest when we were alone together. As she passed me in her preparations, I would reach out and touch her bare toes, and she would rumple my hair and murmur her affection for me.

Again, on the morning of his 87th birthday, he wakes to the memory of his mother’s face, “as I had seen it lighting the Shabbat candles and reciting the Berakhah: ‘Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe. . . .’” “A reverie took shape in me,” he continues, “on the secular blessing given to me and to my students by the highest literature, from Homer and the Hebrew Bible through Dante and Chaucer and on to Shakespeare, Cervantes, Montaigne, Milton, and the tradition of Western literature that culminates in Proust and Joyce.”

It is a remarkable and revealing passage in many ways, not least of all because it moves, almost without pause, from the 87-year-old author’s childhood memory of his mother’s face to his shortlist of the most important artists in the Western literary tradition. No one but Bloom could have made that pivot credible. His relationship to the masterworks of literary art was intensely personal and passionate: a form of love reserved, by most of us, for our closest family members and friends. Unable to sustain his mother’s faith in the covenant, he “turned to the reading and studying of literature in search of the blessing” of “more life,” which he was granted in great abundance, and shared for six decades in the classroom and on the page. We will not see his like again.

Suggested Reading

King James: The Harold Bloom Version

There may be a thousand facets to the Torah, but does Harold Bloom simply misunderstand the King James Bible?

The Life of the Flying Aperçu

Dickstein’s story is not a narrative of apostasy and rebellion; belief and doctrine play a minor role.

A Novel of Unbelief

Religion, faith, and the search for tenure at Harvard underpin a comic novel by Rebecca Newberger Goldstein.

Harold Bloom: Anti-Inkling?

It’s a bit surprising to come across Harold Bloom’s confession that the literary work that has been his greatest obsession is not, say, Hamlet or Henry IV, but a relatively little-known 1920 fantasy novel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In