The Rebbe and the Professor

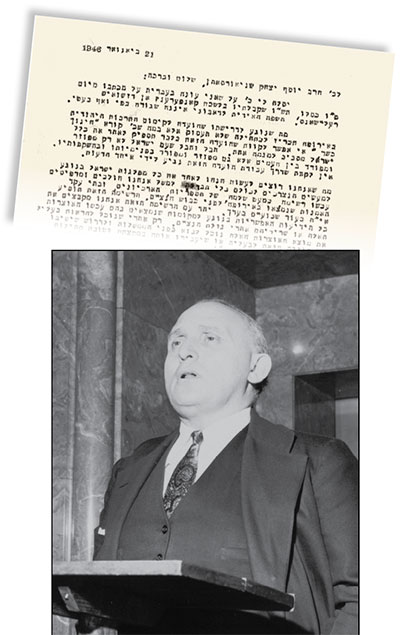

Professor Salo Wittmayer Baron (1895–1989) was born in Tarnów (then Galicia, now Poland) and moved to Vienna, where he earned doctorates in philosophy, political science, and law from the University of Vienna and was ordained as a rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary there. After a short tenure at the Jewish Teachers College in Vienna, he was invited to join the faculty of the Jewish Institute of Religion in New York in 1927. In 1929, Baron was hired by Columbia University, where he became the first scholar to hold a chair in Jewish history at an American university. His A Social and Religious History of the Jews, which began as a series of lectures, was a landmark study of Jewish life and culture from ancient times through 1650. In its 18 volumes he sought to overturn what he famously called the “lachrymose” conception of Jewish history that focused on Jewish suffering rather than an integrated vision of social, religious, and economic history.

In 1936, Baron and the philosopher Morris Raphael Cohen founded the Conference on Jewish Relations in response to the rise of Nazism and the alarming rise of anti-Semitism in the United States. The Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, founded in 1944, was one of the outgrowths of the conference. The commission was first conceived as an attempt to prepare for rebuilding Jewish life in Europe after World War II, but it came to focus on salvaging books, historical documents, manuscripts, and other cultural treasures and then distributing them to Jewish communities around the world. The commission sought the assistance of a wide range of prominent scholars, historians, and academics, as well as Jewish communal leaders and rabbis.

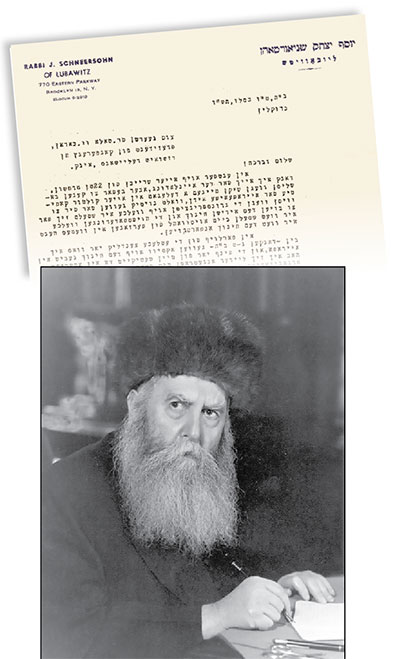

One of the leaders to whom the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction turned was Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (1880–1950), the sixth leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic community. Schneersohn had fought tirelessly in support of Jewish religious life under the tsarist and Soviet governments. Efforts to ensure Jewish religious education, often clandestine, occupied a special place in Schneersohn’s project. He had visited the United States briefly in 1929 and returned after a remarkable escape from the eastern front in March of 1940, settling in Brooklyn. When advised that the old-world patterns of life and piety would not take hold in the foreign soil of America, he reportedly proclaimed, “Amerika iz nisht anderish!” (America is no different!). In the immediate postwar years, he established a national network of Jewish schools and yeshivot for men and women, as well as special “released time” classes for public school students. His charismatic successor and son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994), continued many of these efforts and transformed Chabad-Lubavitch from a relatively small community into a large international organization.

Schneersohn’s answer to Baron’s initial invitation to take part in the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction is respectful but sharp and uncompromising in its rejection of any cultural or educational enterprise that does not accept “Torah and the commandments” as essential. His tone is conversational and pointed: “the last 5–10 years must have opened the eyes of even the blind, and every person with any sort of logical mind must have discerned how deep the European civilization has sunk, what a great abyss lies between it and, le-havdil, the refinement of Torah-life.” However, he does not dismiss the project out of hand.

Rabbi Schneersohn’s letter was forwarded to Baron by Hannah Arendt, who, in November 1945, began working under Baron’s supervision as a researcher for the commission, eventually serving as the successor organization’s executive director. In her letter, dated November 27, 1945, Arendt writes, “I doubt very much that he will recognize us as a ‘Kosher Chinuch’.” Writing to Schneersohn, Baron addresses the Rebbe in the third person, as was common in letters to distinguished rabbinic figures. He describes the work of the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction as an attempt to understand and quantify the devastation wrought by the Nazis, establishing what resources are left and deciding how they may best be used to ensure a Jewish future. As to whether the commission will commit to “kosher education,” Baron wryly notes that “it is impossible to hope that this committee by itself will suffice to unite the entire Jewish people.”

There is no evidence of further communication between the two men, but these letters are marvels of respect and civility, despite disagreement, at a moment of unparalleled historical crisis. The letters from Schneersohn, Baron, and Arendt are held in the Salo W. Baron Papers at the Stanford University Libraries. I wish to thank Mrs. Shoshana Baron Tancer and Mrs. Tobey Baron Gitelle for graciously allowing us to translate and publish Professor Baron’s letter. My thanks to the Chabad-Lubavitch community for their permission to publish a translation of Rabbi Schneersohn’s letter, which was first printed in Iggerot Kodesh (Kehot Publication Society). I thank Zachary Baker, the Reinhard Family Curator of Judaica and Hebraica Collections at Stanford University, for bringing these letters to my attention, and his successor Eitan Kensky for help with the translation.

B”H, 15 Kislev, 5706

Brooklyn

To the distinguished Mr. Salo W. Baron,

President of the Conference on Jewish Relations, Inc.

Peace and blessing!

In response to your letter from the 22nd of Marcheshvan, I thank you for the invitation, but before it is possible to decide whether to send a delegate on my behalf to your culture-commission for European Jews, it will be necessary for me to know something about the foundational principles upon which it seeks to build Jewish education and the principal requirements for the election of persons to whose hands it entrusts education.

Over the course of the past few decades, in which I have—thank God—been active in the field of education in Europe, and the five years of my involvement in America, I have unfortunately encountered more and more movements and organizations that presented the goal of working for Jewish education, but, not having appropriate principles, they—as good as their intentions may have been—not only did not bring any positive results, but, just the opposite, they brought the greatest injuries to Jewish education.

The particular task of Jewish education is to prepare Jewish youth to implement the special tasks of the Jewish people as a whole, and of every Jew in particular, in their lives.

And the task of every Jew is to be a keeper of Torah and the commandments, and Jewish education must instill the youth with pure faith, love of God, love of Israel, love of the Torah, devotion to fulfilling the commandments, trust and

perseverance.

If in the past century, one could still find among Jews those who were intoxicated by the outward brilliance of European culture, imagining that it would be worthwhile to exchange the Jewish Torah-life for it; and if many of them believed that, through assimilation, one could free oneself of Jewish sorrows; and if these same people have, therefore, found it possible to extract the soul from the essence of Jewish education—Torah and the commandments—without which the education remains utterly lifeless, in total opposition to the Jewish character; then the last 5–10 years must have opened the eyes of even the blind, and every person with any sort of logical mind must have discerned how deep the European civilization has sunk, what a great abyss lies between it and, le-havdil, the refinement of Torah-life, and how little one can depend on protection through assimilation . . .

And has there ever been a time such as today, when the Jewish youth, throughout the world as a whole and the Jewish youth of Europe in particular, were more in need of an education that not only protects them from the danger of despair, heaven forfend, but also the reverse, implants in them the greatest courage to sustain the construction of the Jewish people in a holy manner with utter devotion.

The essence of education is for us Jews not only a question of culture, but a question of life and existence, and it is self-evident that a Jewish child can only receive this sort of education through being taught by teachers who are Torah-and-commandments Jews, and are themselves inspired by all the things that they must implant in the Jewish child.

Only the sort of education that corresponds to the aforementioned conditions is kosher and may correctly be called “Jewish education.”

I have—thank G-d—a staff made up of the greatest specialists in the field of Jewish education in general, who are very well acquainted with European Jewry and its particular spiritual needs; I and my entire staff always stand ready to help with all possibilities, in every undertaking that is for the sake of a kosher Jewish education.

I would therefore ask you to inform me of the extent to which it is assured that the activities of your culture commission for European Jews will be conducted according to the principles stated above of a kosher education, an education that should, with God’s help, produce proud Torah-and-commandments Jews.

With respect and blessing,

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn

January 21, 1946

To the Esteemed Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak

Schneersohn,

Peace and blessings:

The esteemed rabbi should forgive me for answering in Hebrew his letter from the 15th of Kislev, 5706, which I received at the office for the Conference on Jewish Relations. To my chagrin, the Yiddish language neither trips off my tongue nor flows from my pen.

With regard to his request that Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction declare, from the outset, that it will only engage in what the esteemed rabbi calls “kosher education”—it is impossible to hope that this committee by itself will suffice to unite the entire Jewish people around a single aim. It is lamentable that the Jewish people are not only scattered and dispersed among the nations, but are also scattered and dispersed internally and in their views. There is no reason to hope that through the work of this commission we will achieve a unity of opinions.

What we wish to do is to unite all the parties of Israel in regard to things that must be done for all, without any distinction. For example, we are proceeding to publish a nearly-complete list of the libraries, archives, and art collections found in Europe before the Nazi conquest. This list will appear, God willing, in about two weeks.

Together with this list, we are gathering all possible knowledge regarding the places in which these collections are now found, or whatever is left after the theft on the part of the Nazis. Only after we can clearly prove the origin of these collections can we come before the governments and demand that they return the stolen property to its owners or transfer it, in part, for the good of other Jewish communities, particularly those in the land of Israel.

This is only one example of the research and intellectual work with which we are occupied. It would be truly worthwhile, in our opinion, if the esteemed rabbi and those who share his views would participate with us in these sorts of efforts. Afterward, the different educators in their various locations will decide what they will do with this knowledge in their respective schools. Of course, many of us hope that this may allow us to help, in some small way, to expand the Torah and restore it to glory in its old centers throughout Central Europe.

I hope that this explanation will set aside all of his doubts and that he can take part in our work, either directly or through his emissaries.

With respect and appreciation,

Shalom Baron

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

For the Many, Not for the Jew

The anti-Zionism embraced by far-left activists who flocked to Labour after Jeremy Corbyn’s election has merged with ancient European Jew-hatred to create a new and virulent strain of anti-Semitism.

Dress British, Think Yiddish

Stanley Kubrick was a New York Jew, fascinated with photography, jazz, and chess. He took evening classes at City College and studied at Columbia with Lionel Trilling.

Freethinker

Melanie Phillips had stumbled into the culture wars by, as she herself describes it, “the staggering tactic of actually observing what was going on.”

Poisoned Gefilte Fish, Broken Heart

In a characteristic turn of phrase, Der Nister wrote that the realization of the possibility of a land for Jews, where they lived under their own sovereignty would be a “brokhe af doyres” (blessing for future generations). The bitter irony is almost unbearable.

Steve Lanset

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson's reply to Professor Baron seems rather churlish and narrow-minded.