Grading Parents

In what is easily the most shocking suggestion in The Blessings of a B Minus, Wendy Mogel urges parents to refrain from talking to their teens about college until 11th grade. “Clench your teeth if you have to,” Mogel recommends. Her point is that college admission has become a tension-filled derby that doesn’t do kids trying to get in to Harvard, or their parents, any good.

Instead, Mogel introduces readers to the concept of bitachon—trust in God. She explains, “parents need to place more emphasis on a loving acceptance of the dizzying spiral of adolescent development than on a narrow, focused effort to make their teenagers college-worthy.” Parents should have a little more faith in their kids not only because it will probably improve family life but because it will help their children develop the skills they need to grow into adulthood. Building self-reliance is a central theme of Mogel’s work. “According to the Talmud, ‘teaching your child to swim’ is a primary parental responsibility . . . because the goal of parenting is to raise our children to leave us.”

Mogel is a clinical psychologist and mother of two whose first book, The Blessing of a Skinned Knee: Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children, made her a superstar. That success was well deserved since the book did a terrific job of exposing why so many parents she counseled were miserable, and so many kids she tested were frustrated. Having illustrated the emptiness of modern-day child rearing, Mogel boned up on Judaism—with its levelheaded approach to real human fallibility and potential—and wrote a handbook for happier, more satisfied, more successful parents and kids.

She admits that for the most part she has her sights set on upper-middle-class and wealthy parents on the East and West coasts, but many of the issues she raises about homework, sleep, college, and chores, will be familiar to a wide swath of American parents.

Mogel is certainly right when she argues that many parents have become so fearful and over-protective that they tend to “help” their children too often instead of letting them experience the world with all (or at least some of) its sharp edges. Parents, according to Mogel, try so hard to “care” for their kids’ every emotional or physical want and need that the home ends up a place where there is no authority and no structure. This leaves children exquisitely aware of their own feelings but not their obligations, either to their families or to the larger community. And as Mogel discovered through her clinical practice and counseling, this overabundance of “care” together with a total lack of authority and moral structure left the kids basically nowhere.

One of the most useful lessons from Skinned Knee is Mogel’s discussion of parental authority. She expertly categorizes the types of parents who have abdicated their authority. There are the parents who are ideologically committed to democracy in the home, the “as long as your grades are good you can treat me like dirt” parents, and the hyperattuned-to-my-rude-kid’s-every-desire parents—all of whom hate the results without knowing quite what to do.

In contrast, Mogel urges something like a “Divine Command theory” of parenting. The first of the Ten Commandments, “I am the Lord, your God . . .” is, she teaches, traditionally taken to establish God’s authority. Mogel then goes on to employ the classic distinction between two categories of commandments, chukim and mishpatim. The latter have an explicable rationale. But chukim are to be followed just because God commands them. Respecting Mom and Dad, Mogel explains, is one of the chukim. There ought to be no confusion about who is in charge. “Parents get fooled,” Mogel writes, “because their kids are such skilled debaters, but children are not psychologically equipped to handle winning those debates . . . They can’t regulate their own TV watching, or monitor their language, or teach themselves good manners.” Establishing who is in charge is actually a way to make kids more secure and ultimately more successful.

From this perspective, it might seem as if Mogel and the recently infamous “Tiger Mother” have a lot in common. After all, Amy Chua’s embrace of parental authority as the means of guaranteeing a child’s success is the reason everyone and their mother has an opinion about Chua’s memoir. Does she take discipline and drive to an abusive extreme or is her way of pushing her kids to excellence better than the soft, self-regarding approach of most Americans?

In fact, Mogel has just as much to teach Chua as she does any other over-achieving, upper-class parent. Chua has really just taken the parenting Mogel is critiquing to the nth degree. Neither Chua nor any of the parents Mogel describes can handle failure. Chua makes absolutely no room for her daughters to try and fail. Not only can’t they fail; only first place is considered success. Chua has nothing to say about her role as a moral force in her children’s upbringing. This omission—her insistence on a discipline that is not grounded in ethics—is her book’s ultimate failing. As Mogel writes in Skinned Knee:

Determined to give their children everything they needed to become “winners” in this highly competitive culture, [parents] missed out on God’s most sacred gift to us: the power and holiness of the present moment and of each child’s individuality . . . By sanctifying the most mundane aspects of the here and now, [Judaism] teaches us that there is greatness not just in grand and glorious achievements but in our small, everyday efforts and deeds.

Mogel writes about the notion of a “good enough” child and urges parents to recognize that they can’t control outcomes. Chua, and lots of other parents, would do well to bookmark the page.

Mogel’s new book is meant to extend this approach from childhood into adolescence. “Using the Jewish teachings I’d written about, I was able to resist the extremes of overprotection, over-scheduling, overindulgence,” Mogel triumphantly explains early in The Blessings of a B Minus. She had confidence in her abilities to parent her girls through their teen years because, she writes, “when it comes to teenagers, I am a professional.”

Mogel is, of course, right that as kids begin to leave childhood, parents have to begin to let go so that they can blossom into individuals. This process can be difficult to watch, but by providing example after example of families she’s counseled, Mogel gives readers a pretty good sense of what doesn’t work. One weakness of B Minus, however, is that the practical solutions Mogel now imparts have little to do with Judaism and much more to do with a conventional and entirely unsurprising liberalism. At any rate, Mogel is certainly selective with her Jewish precepts in this new book.

In Skinned Knee Mogel extolled the virtues of Shabbat. She took great pains to explain the reasons, morality, and importance of separating out this bit of time every week to shut off, slow down, and recover. Carving out such “sacred” space for the family to come together at a meal to talk and reconnect, she argued, is especially important in our current over-scheduled, over-networked, and endlessly stimulated lives. Not that she insisted on Orthodox observance to derive these benefits. “Now that the children are bigger we are looser about Shabbat,” she wrote, “but the one thing that remains unchanged and inviolable is our leisurely Friday night dinner.”

But what was inviolable in Skinned Knee becomes very much so in B Minus. Now that the kids are teenagers, with different circadian rhythms and developing brains, getting them to sit down to dinner with the rest of their family every Friday night is not even physiologically realistic according to Mogel. She recommends that you remain flexible, “respect your child,” and allow that your teen may not make it to the table every week or if he does he might not stay at the table very long. What happened to commandments, chukim, and absolute respect for one’s parents? And what kind of parental message is it to make these things inviolable until the age of, say, 14?

Consistency is a problem in B Minus. For instance, Mogel loves the notion of sanctification as a means of modeling good behavior when it comes to alcohol. Parents who drink wine at Shabbat dinner to sanctify the experience are showing their kids that there is a time and place for drinking. And she is adamant that parents not take this as an endorsement for letting underage kids drink at home with their friends. But then she urges parents to develop what she defines as a sense of proportion and realism when it comes to drinking, drugs, and sex.

To Mogel’s way of thinking, vices like drugs, and experiences like premarital (and unprotected) sex are part of the teen landscape nowadays and parents are therefore better off giving their kids space to talk about these subjects if they so choose, and to lay down realistic rules in any case. “Give them rules about safety and decency . . . Do not endorse risky behavior, but recognize and accept that it’s probably going to happen.” What happened to traditional Jewish teaching in this case? Perhaps it was hard to find the right rabbinic saying when Mogel’s advice actually ran up against traditional values: Sex is meant to be enjoyed within the confines of a loving, sanctified relationship, not by unattached teenagers with raging hormones.

Indeed, Mogel’s decision to ignore Jewish wisdom in this case makes The Blessings of a B Minus less brave and less useful (less of a blessing, one is tempted to say) than her first book. Whether her selective use of Jewish teachings derives from her personal convictions or from a sober assessment of what her audience would accept, the result is a book that falls short of its stated purpose.

Mogel does offer some terrific ideas for parents of teens that have nothing to do with Jewish teachings, however, and these should be religiously observed by every Tiger Mom and over-parent out there: Kids should get paying jobs and do chores. The menial labor, low-skilled job will teach your teen that “service is not servility and that any job can be done with dignity. It motivates you to work hard in school when you see how easily low-wage/low-skilled jobs become boring or repetitive.”

As for the chores, well, again, Mogel wants kids to learn the value of “menial” work rather than exclusively “exalted” work like studying and homework. A working mother of four once explained a perfectly compatible but more practical reason to me. When each child got to be tall enough to reach the knobs on the washing machine, she taught them how to do laundry. “I was working,” she said, “so if they needed clean clothes they had to learn how to get them that way.”

Suggested Reading

Golden Books

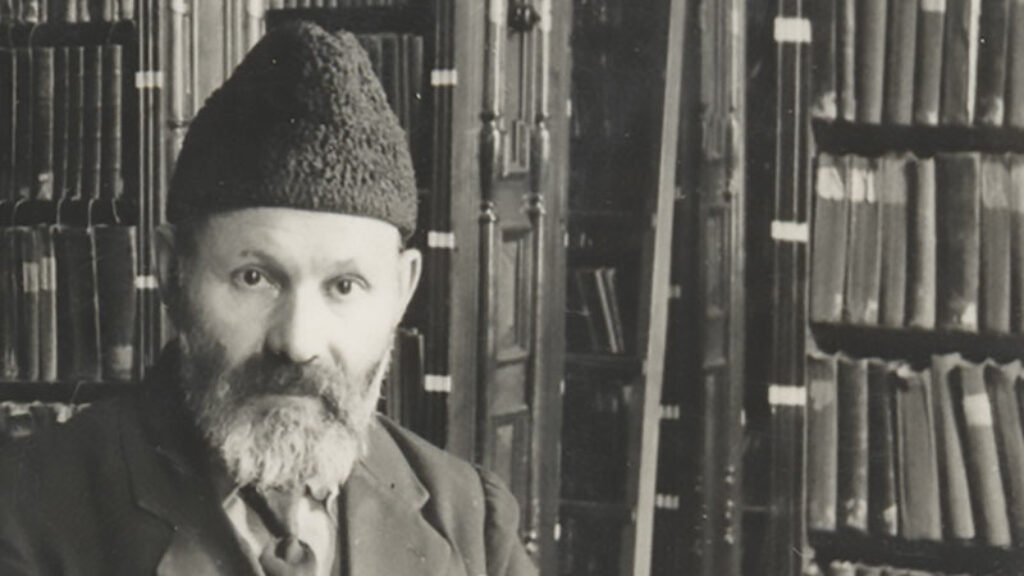

Three decades ago, Allan Nadler went to Vilna to reclaim books that the Nazis had plundered from YIVO, or so he thought. Dan Rabinowitz’s Lost Library solves the mystery—and raises important questions.

The Ubiquitous Gabirol

Solomon ibn Gabirol plunges into poetry, writes S. Y. Agnon, medabek atzmo be-charuz: glued to his craft, beading words with devotion.

Category Error

What is lost when the books of the Hebrew Bible are read as philosophy?

On Literary Brilliance and Moral Rot

Why did the prestigious publishing house Gallimard want to publish three vilely anti-Semitic pamphlets by Louis-Ferdinand Céline? And is he still worth reading?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In