The Vanishing Point

I remember the first time I looked through my parents’ copy—every suburban Jewish family had one—of photographer Roman Vishniac’s volume A Vanished World. It was 1988 and I was 11 years old; I pored over the photographs of bearded men and basement-dwelling children, surprised to find myself captivated. I was vaguely aware that most of the people in the pictures had been murdered, but that was not what haunted me. The photographs reminded me of my artist mother’s favorite paintings by Rembrandt—where the light, as she described it, seemed to come not from any external source, but from within the figures’ faces.

Ten years later, I began my doctoral work in Yiddish literature and came to know not only many of the dimensions of that “vanished world” (a place, as it turned out, where I would never want to live) but also the strange fire that burned within it. A half-century before the Holocaust, Ashkenazi culture was already ignited by what scholars call the ethnographic impulse—the urge its writers and artists felt to record whatever they could of a life and language that were already considered on the brink of extinction. Countless Yiddish stories, plays, and films include gratuitous scenes or descriptions of holiday observances, superstitions, ritual objects, food, and details of dress. The shtetl nostalgia that still flourishes in American Jewish life had already begun, fifty years before the gas chambers horrifically ended the argument or, at least, transferred it to other continents in shadowed form.

Ten years later, I began my doctoral work in Yiddish literature and came to know not only many of the dimensions of that “vanished world” (a place, as it turned out, where I would never want to live) but also the strange fire that burned within it. A half-century before the Holocaust, Ashkenazi culture was already ignited by what scholars call the ethnographic impulse—the urge its writers and artists felt to record whatever they could of a life and language that were already considered on the brink of extinction. Countless Yiddish stories, plays, and films include gratuitous scenes or descriptions of holiday observances, superstitions, ritual objects, food, and details of dress. The shtetl nostalgia that still flourishes in American Jewish life had already begun, fifty years before the gas chambers horrifically ended the argument or, at least, transferred it to other continents in shadowed form.

I didn’t know any of this yet. All I saw, then, was the light within.

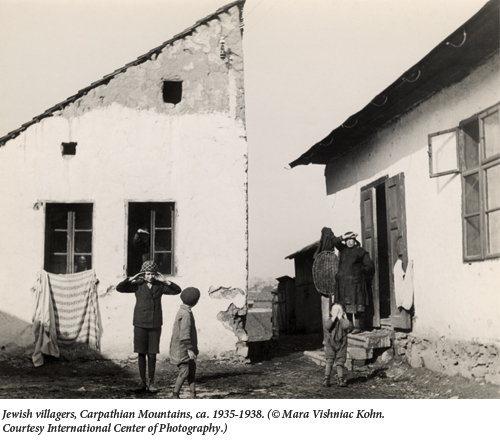

At “Roman Vishniac Rediscovered,” a major retrospective at New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP) which will travel domestically and internationally later this year, the first thing I saw was a very different kind of light. The image that greets visitors to the exhibit is a floor-to-ceiling enlarged print featuring two crumbling houses, with two women and two children standing in front of them, along with two more women looking out through the houses’ windows. Taken in the Carpathian village of Munkatsh [Mukachevo] in the late 1930s, it is, as a wall label points outs, “a nearly perfect photograph.” The two houses’ slanting roofs form a striking pattern of angles, and the figures appear in a startling symmetry of indoors and outdoors, young and old, brightness and shadow. But what arrests the viewer are the women’s faces. On a blinding sunny day, the two women in the foreground and the women in the windows squint at the viewer beneath hands raised to block out the light. There is often an uncomfortable voyeurism implicit in photographs of foreign lives. But this image was the first time I ever felt that the people in such photographs were in fact looking back at me, shielding their eyes to see me better, wondering what I was thinking.

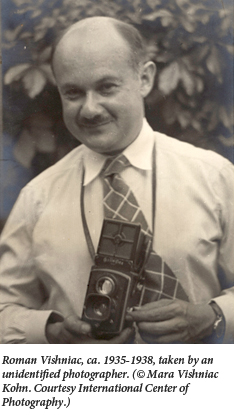

Maya Benton, the 37-year-old Yiddish-speaking exhibit curator whose mother grew up in a displaced persons camp that Vishniac documented, has succeeded tremendously in rescuing Vishniac from the amber in which his most iconic images are preserved. As she explained to Alana Newhouse in a long New York Times Magazine story in 2010, Vishniac’s reputation rests on only a few hundred images out of the thousands he produced, and those few images are burdened with false mythologies perpetuated by the photographer himself—that he used a hidden camera, for instance, or that his was a “secret mission” intended to preserve a culture, or that the impoverished religious Jews he photographed were representative of that “vanished world.” But the exhibit itself is less about debunking myths than about revealing the fullness of a misunderstood artist’s career. “Most of the images here have no mythology attached to them, because they’ve never been seen before,” Benton told me. “It’s a body of work that introduces one of great photographers of the 20th century.”

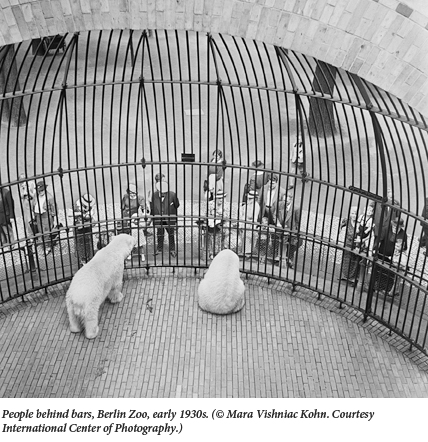

Vishniac was nothing if not versatile, moving Zelig—like through the cataclysms of his time. Born and raised in Moscow by affluent, secular Jewish parents who fled to Berlin after the 1917 Revolution, Vishniac studied biology before joining his parents in Berlin, where he established himself as a street photographer with a modernist eye akin to that of Henri Cartier-Bresson. His early work, shown here for the first time, is visually masterful but emotionally cool, marked by an outsider’s playful irony. Among the shots of German butchers and chimney sweeps, one image struck me as strangely resonant: a photograph of polar bears. Taken from behind the bears as they gaze out of their cage at spectators, the photograph shows laughing children in lederhosen and their overly delighted parents from the point of view of the caged animals. The title is “People Behind Bars, Berlin Zoo.” On the other side of the exhibit hall, in a photo where Vishniac poses his young daughter in front of Nazi phrenology machines, the playful caption is suddenly no longer a joke.

Vishniac was nothing if not versatile, moving Zelig—like through the cataclysms of his time. Born and raised in Moscow by affluent, secular Jewish parents who fled to Berlin after the 1917 Revolution, Vishniac studied biology before joining his parents in Berlin, where he established himself as a street photographer with a modernist eye akin to that of Henri Cartier-Bresson. His early work, shown here for the first time, is visually masterful but emotionally cool, marked by an outsider’s playful irony. Among the shots of German butchers and chimney sweeps, one image struck me as strangely resonant: a photograph of polar bears. Taken from behind the bears as they gaze out of their cage at spectators, the photograph shows laughing children in lederhosen and their overly delighted parents from the point of view of the caged animals. The title is “People Behind Bars, Berlin Zoo.” On the other side of the exhibit hall, in a photo where Vishniac poses his young daughter in front of Nazi phrenology machines, the playful caption is suddenly no longer a joke.

Many American Jews have come to see Vishniac as he retroactively presented himself in A Vanished World: as a prophet who foresaw the destruction of Eastern European Jewry before his naïve subjects did, and who poured his soul into preserving those vanishing people on film—the cheder boys with cherubic faces out of a Renaissance fresco, the aged rabbis lit from within like Rembrandt’s portraits of Jews centuries earlier—in the innocent moments before their tragic murders.

Intellectuals love to insist that the reality is more complicated than the myth. But in Vishniac’s case, the reality is actually simpler. Vishniac was on assignment. Just as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange were sent by the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s to document American poverty in the South and West, Vishniac was commissioned by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (“the Joint”) from 1935 to 1938 to document Jewish poverty in the East.

The ICP show’s greatest success is in placing Vishniac firmly in the context of social documentary photographers of his time. His explicit assignment was to photograph people who were obviously poor and obviously Jewish (hence the preponderance of exhausted porters and bedraggled children, as well as men in traditional dress) and to document the Joint’s relief work in action so that American Jews would be moved to donate money and would know where their dollars were going. In the exhibit, visitors can see the brochures, promotional literature, and newspaper spreads featuring his images of the suffering Jewish poor.

The ICP show’s greatest success is in placing Vishniac firmly in the context of social documentary photographers of his time. His explicit assignment was to photograph people who were obviously poor and obviously Jewish (hence the preponderance of exhausted porters and bedraggled children, as well as men in traditional dress) and to document the Joint’s relief work in action so that American Jews would be moved to donate money and would know where their dollars were going. In the exhibit, visitors can see the brochures, promotional literature, and newspaper spreads featuring his images of the suffering Jewish poor.

The immediacy and bluntness of these UNICEF-worthy pleas to the public is jarring. “Hunger, fear and disease stalk through the Jewish streets in Poland,” one pamphlet’s captions read, introducing a Joint-sponsored summer camp. “Backward and defective children who constitute a burden for the coming generations are placed in institutions where wholesome nourishment and kindness improve their physique.” The famous image of “Sara,” an apparently bedridden girl with flowers painted on the crumbling wall behind her, was featured on the Joint’s letterhead. “There was nothing ironic about Vishniac’s project,” Benton reminded me. “He was trying to encourage people to donate food and medicine.” It was only when his subjects were incinerated that the meaning of the photographs began to change.

Was Vishniac complicit in the schmaltzification of his most famous images? Nobody who has read his captions for A Vanished World can doubt it. One can hardly make out the text—much of which is misleading at best—over the strains of a tiny violin. (“I know of a situation where murderers broke into a yeshiva,” he writes in a typical passage, decades after the fact. “The Talmudists went on arguing, trying to reach an answer before their slaughter—so they could enter the world of God, of eternity, with greater knowledge. This is Judaism.”) The exhibit’s display of Vishniac’s scrapbook, which shows how he collected the many popular reprints and illustrations derived from his iconic photographs, also makes clear how aware he was of what his work became.

Was Vishniac complicit in the schmaltzification of his most famous images? Nobody who has read his captions for A Vanished World can doubt it. One can hardly make out the text—much of which is misleading at best—over the strains of a tiny violin. (“I know of a situation where murderers broke into a yeshiva,” he writes in a typical passage, decades after the fact. “The Talmudists went on arguing, trying to reach an answer before their slaughter—so they could enter the world of God, of eternity, with greater knowledge. This is Judaism.”) The exhibit’s display of Vishniac’s scrapbook, which shows how he collected the many popular reprints and illustrations derived from his iconic photographs, also makes clear how aware he was of what his work became.

But the exhibit succeeds too well in demonstrating the tremendous range of Vishniac’s work for any viewer to see him as another Marc Chagall or Isaac Bashevis Singer, a talented artist who retreated into milking the past for pathos. An entire darkened room is devoted to screenings of his scientific microphotography, a field he pioneered for decades. Other displays show him hustling for work as an impoverished immigrant. A series of Chinatown images was part of a failed Guggenheim application. In his New York apartment, he made remarkable portraits of Einstein and (yes) Chagall, among other famous figures, and took pictures in New York’s nightclubs. One case shows his photos of a bar mitzvah in Queens in 1948.

His commissioned work also shows astonishing versatility. Some of the exhibit’s finest images are from Vishniac’s first assignment documenting Jewish social services in Germany: A photo of a classroom in a Jewish middle school in Nazi Germany feels exquisitely alive, its astonishingly familiar-looking children sneaking looks at the camera, a girl’s silver barrette gleaming in the light. A project on Werkdorp, a Zionist vocational farm in the Netherlands, shows its young Jewish subjects as hardy construction workers, building a bright future in stunning shots taken from below, looking up

toward a shining sun. The captions describing the young subjects’ murders feel, for the first time, not inevitable but shocking.

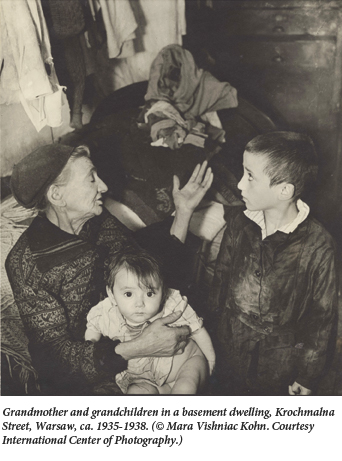

And then, of course, there are the Eastern European works. And they are captivating, all the more so because the empathy, which seems so absent from Vishniac’s earlier work, feels entirely genuine. Here, even the pictures that playfully echo famous artwork—like one of the Jewish quarter in Bratislava, where a child carrying a hoop down a cobblestone lane seems like a deliberate shadow of de Chirico’s “Mystery and Melancholy of a Street”—do so with an unprecedented intimacy. An image of a secular, lipsticked woman in Satu Mare (hometown of the Satmar Hasidim) has no irony to it. A series shot in basement apartments on Warsaw’s impoverished Krochmalna Street (where Bashevis Singer grew up) resembles Jacob Riis’ famous photos in How the Other Half Lives, but the light Vishniac draws from his subjects transcends charity. As these people looked at me through the camera’s lens, I no longer felt like a spectator at the Berlin Zoo. Instead I felt privileged, a witness to captured beauty.

And then, of course, there are the Eastern European works. And they are captivating, all the more so because the empathy, which seems so absent from Vishniac’s earlier work, feels entirely genuine. Here, even the pictures that playfully echo famous artwork—like one of the Jewish quarter in Bratislava, where a child carrying a hoop down a cobblestone lane seems like a deliberate shadow of de Chirico’s “Mystery and Melancholy of a Street”—do so with an unprecedented intimacy. An image of a secular, lipsticked woman in Satu Mare (hometown of the Satmar Hasidim) has no irony to it. A series shot in basement apartments on Warsaw’s impoverished Krochmalna Street (where Bashevis Singer grew up) resembles Jacob Riis’ famous photos in How the Other Half Lives, but the light Vishniac draws from his subjects transcends charity. As these people looked at me through the camera’s lens, I no longer felt like a spectator at the Berlin Zoo. Instead I felt privileged, a witness to captured beauty.

Most of Vishniac’s photographs appeared only in brochures and newspapers at the time. But in January 1944, YIVO in New York mounted an exhibit of his Eastern European images—at a time when his Yiddish-speaking American audience knew what was happening to their friends and relatives in Europe, but also knew how little could be done. The Joint’s attention by then had shifted from relief to rescue, and the ICP exhibit includes a letter Vishniac sent to President Roosevelt along with his photographs, pleading for intervention. Yet the situation was close to hopeless then, and one senses that everyone knew it. In a spare and quiet room, the exhibit achieves something wondrous: using Vishniac’s original mounted prints, with Yiddish and English captions mostly mentioning only the towns and cities depicted, it recreates that YIVO exhibit from 1944.

The images in this section of the exhibit are familiar. Most of them—the anguished young woman facing the resigned old man, the little boys gathered over open Hebrew books, the dark-haired bearded man gazing up over wire-rimmed glasses—are the same photographs eventually immortalized in A Vanished World. More significantly, the YIVO exhibit marks the beginning of Vishniac’s descent into amber. It became the basis for Vishniac’s Polish Jews, whose publication by Schocken in 1947 began the process of canonizing this perspective on Eastern Europe in the minds of American Jews. The book’s preface, by Abraham Joshua Heschel, was later expanded into another influential elegy for Eastern European Jewry, The Earth Is the Lord’s. Heschel’s preface originated as a talk at YIVO in 1946. When he finished, the secular Jews assembled spontaneously rose and recited Kaddish. It is difficult, generations after the fact, to penetrate the fog of ritualized and bowdlerized memorials to sense the power these images once held.

The images in this section of the exhibit are familiar. Most of them—the anguished young woman facing the resigned old man, the little boys gathered over open Hebrew books, the dark-haired bearded man gazing up over wire-rimmed glasses—are the same photographs eventually immortalized in A Vanished World. More significantly, the YIVO exhibit marks the beginning of Vishniac’s descent into amber. It became the basis for Vishniac’s Polish Jews, whose publication by Schocken in 1947 began the process of canonizing this perspective on Eastern Europe in the minds of American Jews. The book’s preface, by Abraham Joshua Heschel, was later expanded into another influential elegy for Eastern European Jewry, The Earth Is the Lord’s. Heschel’s preface originated as a talk at YIVO in 1946. When he finished, the secular Jews assembled spontaneously rose and recited Kaddish. It is difficult, generations after the fact, to penetrate the fog of ritualized and bowdlerized memorials to sense the power these images once held.

But that power is present in this silent white room. One sees these stunning portraits and imagines standing there in 1944—in Munkatsh, in Lublin, yes, but also in New York, powerless before these people who are looking back through the fading light. And one is permitted to feel once again, as if for the first time, the beauty and anguish of all that was lost.

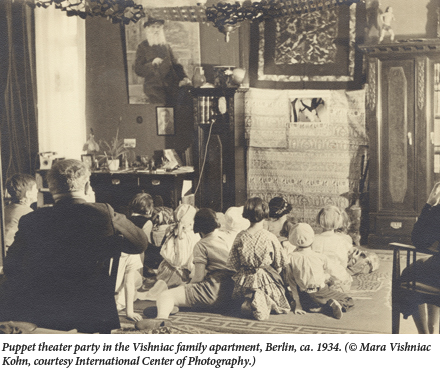

Yet the photograph I found the most uncanny is not one of Vishniac’s many masterpieces, but a mediocre snapshot. In a display of family memorabilia, there is a tiny picture taken at a child’s birthday party in Vishniac’s apartment in Berlin. Like the polar bears, the children sit with their backs to the camera, enjoying a spectacle: an elaborate puppet theater at one end of the high-ceilinged salon. The picture is unremarkable except for another image contained within it. Alongside the puppet theater, on a wood-paneled wall in the elegant room beneath a crystal chandelier, there hangs an enormous photograph of an old man with a long white beard and sidelocks, wearing a caftan and a black hat.

Yet the photograph I found the most uncanny is not one of Vishniac’s many masterpieces, but a mediocre snapshot. In a display of family memorabilia, there is a tiny picture taken at a child’s birthday party in Vishniac’s apartment in Berlin. Like the polar bears, the children sit with their backs to the camera, enjoying a spectacle: an elaborate puppet theater at one end of the high-ceilinged salon. The picture is unremarkable except for another image contained within it. Alongside the puppet theater, on a wood-paneled wall in the elegant room beneath a crystal chandelier, there hangs an enormous photograph of an old man with a long white beard and sidelocks, wearing a caftan and a black hat.

At first I assumed that this was one of Vishniac’s own portraits hanging in his home as an example of his work, as artistic, affectionate, and slightly maudlin as the copies of A Vanished World on the coffee tables of suburban Jewish homes—or, if I were cynical, as offensively schlocky as the “rabbi” puppets I saw for sale in Poland twenty years ago. But the snapshot was dated 1934, and Vishniac’s Eastern European work only began in 1935. As I squinted at the picture within the picture, I recognized the old man from a photo on the other side of the same display case. It is Roman Vishniac’s grandfather.

Is there something kitschy or maudlin about this larger-than-life portrait of tradition in this opulently modern room, this aged Torah-bound ancestor gazing down on these secular puppet-watching children? Maybe, but I doubt it. As I stared at this snapshot amid the detritus of a vanished world, I could detect no irony, no voyeurism, no caged bears or people on display, no puppet theater of the past. I saw only a family memory of a person who once lived and loved the people in the room.

Is there something kitschy or maudlin about this larger-than-life portrait of tradition in this opulently modern room, this aged Torah-bound ancestor gazing down on these secular puppet-watching children? Maybe, but I doubt it. As I stared at this snapshot amid the detritus of a vanished world, I could detect no irony, no voyeurism, no caged bears or people on display, no puppet theater of the past. I saw only a family memory of a person who once lived and loved the people in the room.

Suggested Reading

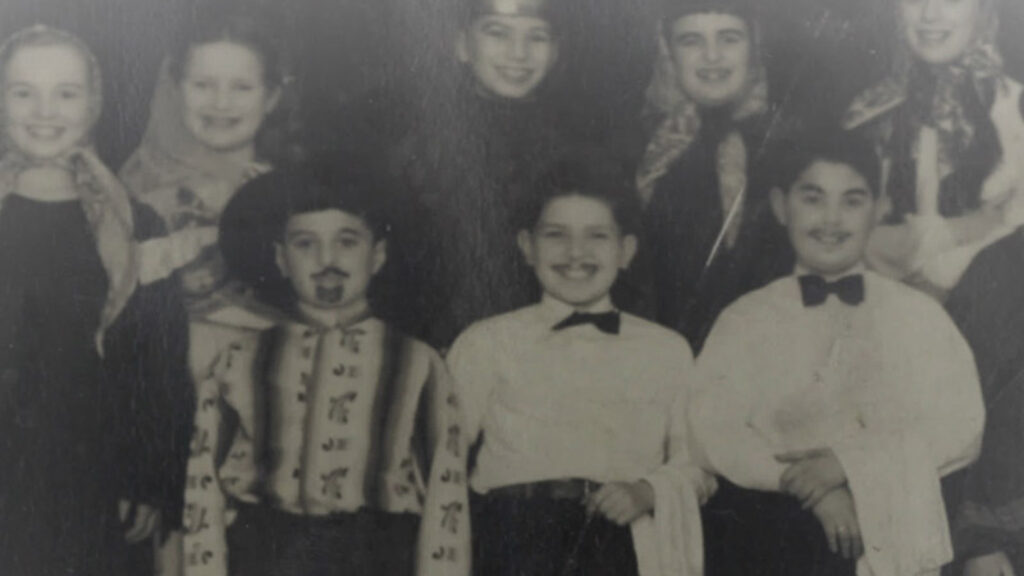

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

The War on History

"People have often asked me if something like the revisionist Israeli historiography to which I contributed in the late 1980s exists on the Palestinian side."

East Meets West

Following the Six-Day War, the East German government and the West German far left demonized Israel time and again, often vilely equating it with the worst thing in their own nation’s history: Nazism.

“Whoever Is Hungry, Come and Eat”? From the Babylonian Poor to the Ashkenazi Elijah

Why do we begin the seder by inviting “whoever is hungry” to come and eat? Aren’t the guests already at the table? And why do we do it in Aramaic? It has something to do with Babylonian magic bowls . . .

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In