Hollywood’s Anti-Nazi Spies

With the recent publication of Hollywood and Hitler: 1933–1939 by Thomas Doherty and The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand, Hollywood’s business dealings with Nazi Germany in the 1930s have become a renewed subject of historical controversy. (See Stuart Schoffman’s review on page 17.) The papers of the Jewish Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles’ Community Relations Committee (held in the Special Collections of the Oviatt Library at California State University, Northridge) provide a surprising and—until now—unknown counterpoint to this discussion. The Northridge archives show that from 1934 until 1941 the same prominent Jewish studio heads who have come in for criticism, including Louis B. Mayer, Emanuel Cohen, and Jack Warner, secretly funded informants to infiltrate Nazi groups operating in Los Angeles. Working behind the scenes with local and federal law enforcement agencies, Congress, and the Justice Department, the Jewish executives of the motion picture industry played a key role in funding the American Jewish effort to resist the rise of Nazism in the United States.

In the 1920s the few Nazi Party members and sympathizers in America had kept to themselves. Most of them were recent immigrants from Germany who established small clubs in the cities in which they settled and waited for “der Tag,” the day when they could return home to a redeemed, new Germany. With the ascension of Adolf Hitler to power in 1933, these fragmented Nazi cells quickly organized into a single, national organization called the Friends of the New Germany. FNG’s mission was to spread National Socialism and fascist ideas throughout the United States in preparation for the coming “Hitler Revolution” in America.

In March 1933, FNG opened the Aryan Bookstore at Ninth and South Alvarado streets in downtown Los Angeles. The shop sold pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic newspapers, leaflets, and books on the Jewish-Bolshevik threat in the United States; the promise of National Socialism; and the “Hitler Miracle” in Germany. That spring and summer, the group held public rallies and sponsored weekly lectures to attract new members. The following year, more than 50,000 people attended an FNG rally held in Madison Square Garden. Particularly interested in converting American veterans to their cause, FNG reached out to members of the American Legion and other veterans’ groups in the city.

The effort to recruit American veterans roused the suspicions of Leon Lewis, a Jewish attorney, veteran, and former first national executive secretary of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). Working within veteran circles in the city, Lewis quickly and discreetly recruited several non-Jewish veterans to infiltrate FNG, established a rudimentary code (the Los Angeles headquarters of FNG was known as 9-Minus, FNG in New York was 9-Plus, and so on), and set up procedures for reporting.

It did not take the veterans long to discover the nefarious political intentions of the Nazi group. Lewis’ agents provided eyewitness accounts of secret meetings between FNG leaders and Nazi Party officials held on board German merchant marine ships in the Port of Los Angeles, the smuggling of large amounts of cash, and the surreptitious importation of thousands of pounds of Nazi literature produced in Berlin for distribution in America. Perhaps the most disconcerting discovery was the organization of a private, brown-shirted militia training in urban street-fighting techniques and taking shooting practice in the hills above Hollywood. The veterans also reported that FNG officials had solicited their help in infiltrating the California National Guard in order to secure the floor plan of the Guard’s Southern California armory so that they would be ready for “der Tag,” now the day when the Hitler Revolution would begin in Los Angeles.

The veterans were stunned by the magnitude of the conspiracy they uncovered. Realizing that further surveillance was required, Lewis, who had paid them largely out of his own pocket, set out to secure the funding he would need to continue the operation. He turned first to B’nai B’rith, the parent organization of the ADL. Divided by internal squabbles as well as debates over the propriety of “spying,” B’nai B’rith could not help Lewis. Next, Lewis approached the group he referred to as “the monied men” of Jewish Los Angeles: the second- and third-generation descendants of the city’s 19th-century Jewish pioneers. Lewis was confident that these men—bankers, real estate developers, merchants, judges, and doctors—would rally to the cause because “[they] had more to lose and more to be afraid of [from the Nazi threat] than all . . . of the local B’nai B’rith membership combined.” After hearing his accounts of Nazi activity in the city, these men promised $5,000 to fund the investigation. Eight weeks later, the “monied men” had only raised $1,000 and demonstrated little resolve to contribute the remainder. Los Angeles, Lewis wrote to a colleague, was the “toughest city in the country in which to raise money for any purpose.”

It was only at this point that Lewis turned to the Jews of Hollywood. These men were Eastern European immigrants, still new in town, and, as Neal Gabler has described them, “fresh from the East, with the disreputability [of the motion picture business] clinging to them like tar.” They, and their products, were also special targets of FNG’s anti-Semitic propaganda, so Lewis hoped that they would recognize the threat that local Nazism posed and support his network of spies.

A special dinner meeting of Hollywood’s Jews was called at the Hillcrest Country Club, which had been founded in the 1920s by Jews who had been excluded from membership elsewhere. On March 13, 1934, a parade of cars carrying studio heads, directors, producers, screenwriters, and actors rolled past Hillcrest’s unmarked stone gates at 10000 Pico Boulevard. Among those in attendance that night were Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio executives Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, Columbia Studios’ production chief Sam Briskin, Paramount Studios’ head Emanuel Cohen, and RKO production executive Pandro Berman. Producers David O. Selznick, Harry Rapf, and Sam Jaffe, along with film directors Ernst Lubitsch and George Cukor, were also in attendance. At dinner, Leon Lewis addressed the group, reporting that the now eight-month-old investigation had cost $7,000, much of which he had provided. If his covert surveillance work was to continue—and his findings so far suggested that it was imperative—Lewis told the assembled moguls that they would have to take responsibility for the operation.

His dinner guests were attentive. Just seven months earlier, Catholic Church officials had organized a nationwide protest and threatened a national boycott of motion pictures if Hollywood did not capitulate to a production code written and monitored by their chosen representatives. Church officials had summoned the studio executives to a meeting with Archbishop John Joseph Cantwell of Los Angeles. At the meeting, distinguished attorney and Catholic lay leader Joseph Scott had explicitly warned the movie men that some groups in America sympathized with Nazi aims and were organizing to attack Jews in America. “What is going on in Germany could happen here,” Scott told the group, which had included Mayer, Cohen, Briskin, Universal Studios’ producer Henry Henigson, and Paramount’s legal counsel Henry Herzbrun, all of whom were at the Hillcrest meeting. It is hard to imagine that Joseph Scott’s words weren’t ringing in their ears as Lewis confirmed the extent of Nazi activity in the city in startling detail.

The minutes of the Hillcrest meeting show that local Jewish community leaders Rabbi Edgar Magnin, Judge Lester Roth, and banker Marco Hellman all spoke up in support of the proposed program. But the movie men were the decision-makers in the room. Louis B. Mayer was emphatic: “I for one am not going to take it lying down. Two things are required, namely money and intelligent direction . . . it [is] the duty of the men present to help.”

Irving Thalberg endorsed Mayer’s position, as did the rest of the attendees. MGM producer Harry Rapf moved that a committee composed of one man from each studio be appointed, along with prominent members of the local Jewish community. Thalberg, Emanuel Cohen, and Jack Warner all pledged to raise $3,500 from their studios. Universal committed to $2,500, and Pandro Berman committed RKO to $1,500, pointing out that RKO had only eight Jewish executives. The smaller studios—Fox, 20th Century, and United Artists—each pledged $1,500. Phil Goldstone and David Selznick were asked to raise $2,500 each from agents and independent producers. Within two months, $22,000 (the equivalent of $384,000 in 2013 dollars) of the promised $24,000 had been raised by the new Los Angeles Jewish Community Committee (LAJCC).

Between September 1933 and March 1934, while Leon Lewis was searching for financial support, he was also working to secure the political cover his agents might one day require. In March 1934, Congress approved funding for a national investigation into subversive Nazi propaganda activity in the United States. The congressional committee, which would eventually become the House Un-American Activities Committee, was led by Congressman Samuel Dickstein of New York and John M. McCormack of Massachusetts.

There is no evidence of the counsel that Lewis provided in the congressional committee’s papers in Washington, but, at a time when political anti-Semitism in the United States was escalating, it is not surprising that Lewis and his Jewish colleagues deliberately maintained a low profile. The Northridge archives show that Lewis traveled to Washington and consulted directly with Congressman Dickstein. Impressed with the information the undercover operation had gathered in Los Angeles, Dickstein named Lewis West Coast counsel to his committee, thus giving Lewis’ agents political cover if their covert activities ever became public.

Between November 1933 and August 1934, Lewis provided evidence of Nazi propaganda activities in Los Angeles, prepared a witness list for the committee’s field visit to Los Angeles, and even drafted the questions the committee used to interrogate those witnesses. When the committee’s final report was issued in early 1935, Lewis was asked to comment on the final draft before it was published. However, neither Lewis nor Congressman Dickstein (who was also Jewish) ever made the work of the LAJCC public.

In December 1934, after the House committee had visited Los Angeles and completed its national investigation of suspicious Nazi propaganda activities across the country, Leon Lewis informed the leaders of the LAJCC that their work was done. Nazis in the city had scattered, Lewis told them, and new federal legislation would make it much more difficult for foreign agents to spread seditious propaganda. After 16 months of exhausting work, Lewis informed the Hollywood bosses that their fight against Nazism in Los Angeles was over and that he was returning to his law practice.

Lewis turned out to be mistaken on both counts. During 1935, FNG re-emerged as the German-American Bund, and over the next six years Nazi-influenced political activity and anti-Semitic incidents accelerated in Los Angeles. The Bund continued to spread National Socialist propaganda in Los Angeles, partnering with many of the more than 400 domestic fascist groups that emerged in the city between 1934 and 1941. Leon Lewis did not return to his law practice, but, instead, continued to direct Hollywood’s spies through the end of World War II.

The information collected and distributed by Hollywood’s spies between 1933 and 1941 was used in several federal investigations and prosecutions including the next iteration of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1938, known as the Dies Committee: the 1942 federal indictment of William Dudley Pelley, whose fascist Silver Shirt party was modeled on the Nazi party, for sedition and treason (while the sedition charge was dropped, he was still sentenced to 15 years); and the 1944 federal sedition trial of 23 Nazi foreign agents, including “Gauleiter” Herman Schwinn, leader of the German-American Bund in Los Angeles. During these years, the supporting role that the LAJCC and other American Jewish defense organizations across the country played in providing these agencies with information on the Bund and its domestic allies was unknown to the public, and it has gone largely unrecognized by subsequent historians. Although the Hoover Library at Stanford University presently contains, for instance, a report prepared for the Dies Committee on subversive Nazi activity in Southern California, the catalogue citation still fails to mention its Jewish origins.

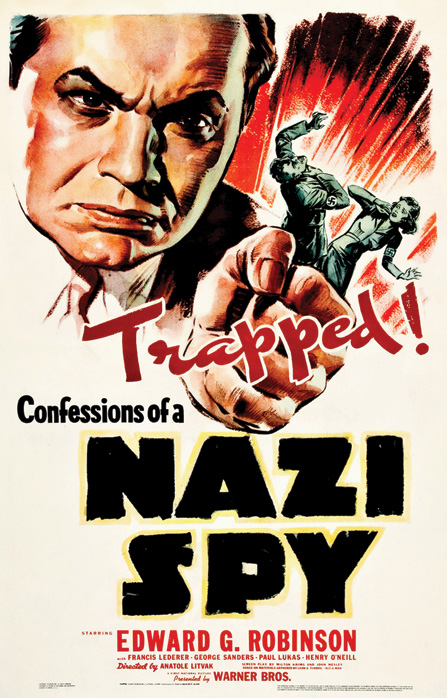

In 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, Warner Brothers released Confessions of a Nazi Spy, starring Edward G. Robinson and George Sanders. Confessions portrayed Berlin’s nefarious efforts to recruit Americans to undermine the U.S. government. The film portrayed the full scope of Nazi activity in America that Hollywood’s spies had been tracking for six years: secret meetings on board merchant marine ships, strong-arm tactics to intimidate German-Americans, and the recruitment of American veterans to their cause. After years of wrangling with domestic and foreign censors over political content in film (a story covered by both Urwand and Doherty in their books), this was Hollywood’s first explicit indictment of Nazism in the United States. What Americans who viewed Confessions did not know, however, was just how long the Jews of Hollywood had waited to tell the story.

Suggested Reading

Radical Kindness and Heroic Dogs: A New Anthology of Yiddish Children’s Literature

Honey on the Page, like the best anthologies, is an eye-opening work of literary history, gleefully introducing a sea of lightly known authors through both their work and through meticulously crafted biographical sketches.

In My Country There Is Problem

Through this new book we get a disturbing picture of how students and faculty in the self-proclaimed progressive movement have demonized and marginalized Israel, its advocates, and anyone who wishes to genuinely learn about the Jewish State.

Mystical Teachings Do Not Erase Sorrow

In Yehoshua November’s new collection, however, it turns out that the difficulties of being a Jewish poet do not primarily flow from being either Jewish or a poet but from the underlying difficulties of life itself.

Spinoza in Warsaw: Fragments of a Dream

“Having rested in his grave for 250 years, Baruch Spinoza came to the conclusion that just lying around like that was without telos” and decided to try to make it in Warsaw. A Yiddish satire, translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.