Pew’s Jews: Religion Is (Still) the Key

A tasteless but revealing old joke goes something like this: Dr. and Mrs. Shapiro of East 78th Street don’t care much for religion, but they are eager to give their daughter Rebecca the best possible education. So they send her to the finest local private school, which happens to be St. Anne’s. All goes well until one day Becky comes home and proudly recites her catechism at the kitchen table, whereupon the normally reserved Dr. Shapiro jumps up red-faced and bangs his fist on the table: “Rebecca,” he cries, “there is only one God, and we don’t believe in Him!”

One of the most provocative findings of the recent Pew Research Center study, “A Portrait of Jewish Americans,” is that a growing minority of self-identified American Jews—22 percent overall and 32 percent among those born since 1980—define themselves as “Jews of no religion.” This means that they declined to specify Judaism when asked about their religion but did say that they identified as Jews in some other way. But what are we to make of poor Dr. Shapiro? Would it be proper to consider him a “Jew of no religion” despite his commitment to the exclusivity of a God in which he no longer believes? Or would he be among the 78 percent of American Jews described as “Jews by religion,” because historical Judaism is still the religion he actively rejects? Being a Jewish atheist may after all be a different sort of thing than being a (formerly) Christian one. And what about the catechism-reciting Rebecca? These are not trivial questions. They get at the deep structure of Jewish life in modernity and the inadequacy of many of the sociological measures we use to describe “Jewish identity.”

The distinction between “religious” and ethnic or cultural—in Israel they would say “national”—Jewishness can prove particularly difficult. Is the proper frame of comparison for American Jews “Catholics, Protestants, and Muslims” or “Irish, Italians, and Koreans”? The truth, of course, is that one cannot answer that question in the abstract because it depends on what you are looking for. But the deeper answer is that the distinction between religion and ethnicity was not native to Judaism at the dawn of modernity, was never uniformly welcomed or accepted, and is still relatively alien to many non-Ashkenazi communities. Perhaps more surprisingly, this distinction apparently fails even today to adequately describe American Jews.

When Abraham Geiger argued, as one of the 19th-century architects of Reform Judaism, that modern Jews had outgrown their need for trappings of peoplehood like language, attachment to land, and a shared ritual life, his deep anxiety over not being considered sufficiently German ran close to the surface. The cultural Zionist Ahad Ha-Am later struck that nerve hard in his great essay “Slavery in Freedom,” which mocked the Jews of Western Europe for reducing Jewishness to a mere religion as a way of seeking acceptance from societies that would never really accept them. Yet even in America, where strategies of acculturation, accommodation, and assimilation have basically worked, American Jews still tend to think of Jewishness in terms of peoplehood from which religion cannot be eliminated. Understanding the implications of this fact seems far more important than the increasingly frantic discussion of denominational market shares.

It is instructive to compare Pew’s “Portrait of Jewish Americans” with its 2012 study, “Mormons in America: Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society.” Like Jews, Mormons represent around two percent of the American population, but that is where the similarity seems to end. Unlike Mormons (a religion that actually grew up in America), Jews overall seem quite certain of their place in American society, relatively untroubled by prejudice and well-integrated—which is one way of reading intermarriage rates approaching 60 percent. But the distinction between Jews and Mormons is most visible when it comes to matters of religion. A whopping 98 percent of Mormons surveyed say that they accept the resurrection of Jesus and 87 percent say that they pray every day. The only comparably high overall numbers for Jews is that 94 percent say they are “proud to be Jewish,” without, however, being able to agree on what precisely that might entail. Even “leading an ethical life” and “remembering the Holocaust” are considered “essential to being Jewish” by only 69 and 73 percent of Jewish respondents, respectively.

Needless to say, the Mormon study offers no category for “Mormons of no religion,” for, by and large, such people regard themselves simply as ex-Mormons. Most Jews surveyed, by contrast (62 percent), say that being Jewish is “mainly a matter of ancestry and culture,” including 55 percent of those who said that they themselves were “Jews by religion.” Most also say (though the question is ambiguous) that one can be Jewish even if one works on the Sabbath (94 percent) or does not believe in God (68 percent). In fact, just 26 percent of Jews surveyed say that religion is very important in their lives, compared to 56 percent of the general U.S. population.

So, are we witnessing a renaissance of secular Jewish life in America, as the increase in “Jews of no religion” (who are also described in the report as “secular or cultural Jews”) might seem to indicate? The answer, at least in statistical terms, is clearly no, but it is important to understand why. Critics have, fairly, pointed out that Pew neglected to ask questions about the meaningfulness of participation in many religiously unmarked but culturally significant activities such as Jewish film festivals, courses in academic Jewish studies, or participation in non-denominational festivals of Jewish learning such as Limmud. There is no reason to deny the significance of these aspects of American Jewish life, and future studies should find ways to include them. Nevertheless, we should still expect to find some indication of a renaissance in secular Jewish culture in the Pew findings if one was really underway.

What we find instead is that Pew’s “Jews by religion” are also much more likely to identify with Jewish culture and peoplehood broadly than their brethren of “no religion.” On the question of whether Jews have a special responsibility to take care of other Jews, 71 percent of Jews by religion answered affirmatively, compared with just 36 percent of the Jews of the “no religion” group. On contributing to a Jewish charity, it was 67 percent to 20 percent. The hallmark of secular national identity in Israel is a sense of attachment to the Jewish State, but here 69 percent of Jews by religion said that they were either “very” or “somewhat” attached to Israel compared with just 45 percent in the no religion category. And in case anyone thinks that Israel’s complicated politics contributed meaningfully to this discrepancy, Pew finds that 85 percent of Jews by religion evince a “strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people,” compared with just 42 percent among Jews of no religion. What is going on here?

Those who read quickly through “A Portrait of Jewish Americans” may well miss the fact that “Jews by religion” does not mean the same thing as “religious Jews.” As the Pew analysts themselves note, “some Jews by religion are non-believers, while some Jews of no religion are ritually observant.” This makes Pew’s decision to describe “Jews of no religion” as “secular or cultural Jews” puzzling. In fact, some secular Jews may be “Jews by religion” in the terms established by Pew, not only because they self-identify as such but because, like Dr. Shapiro, Judaism is still the religion that shapes their denial. What all this suggests is not that secular Judaism or Jewishness is on the rise, but rather that there is a necessary symbiosis between secular and religious Judaism and that the disappearance of religion may spell the collapse of meaningful secular Jewishness as well. Indeed, this may be the secret discovered by Israeli Knesset member Ruth Calderon and other figures associated with the contemporary renaissance of secular (hiloni) engagement with Jewish tradition in Israel. In order to remain strong and, above all, transmissible over time, does secular Judaism, need, as Ahad Ha-Am thought, to sink its roots deep in the generative loam of a tradition through which the Living God presumes to speak? This is not the language of academic social science, but it is not a crazy read of the Pew report, either.

Pew’s “Jews of no religion” should not be described as “secular Jews,” rather they are that part of the Jewish community that is increasingly alienated, impatient, or in many cases simply uninterested in Jewishness in any of its forms. Mostly, they are looking for the exit door. While 91 percent of “Jews of religion” who are raising children say that they are raising their children Jewishly in some way, 67 percent of “Jews of no religion” who have children say that they are not raising their children to be Jewish at all. That is called voting with one’s (children’s) feet.

Reform Rabbi Leon Morris of Sag Harbor may have ruffled feathers when he opined in Ha’aretz that Pew’s Jews of no religion “are neither Ahad Ha’Am nor Ruth Calderon,” but instead betray “an identity that is not only absent of faith, Torah and mitzvot, but also largely absent of anything that matters much at all” with respect to Jewishness. Yet that conclusion is hard to avoid. One of Pew’s most important and no doubt troubling findings (in Chapter Seven) is that “Jews of no religion” are no more involved in the Jewish community than people of “Jewish background” (born Jews who do not identify as such) and people of Jewish affinity (non-Jews who identify in some way with Judaism—often Christians who identify with Jesus as a Jew).

The path to Jewish peoplehood in America, in other words, runs directly through religious communities. It is not just that Jews by religion are exponentially more likely to know a Jewish language, join any kind of Jewish organization, feel committed to Israel or to a larger Jewish people, or decide to raise their children as Jewish in any sense, as described above. It is that the overall decision to take Jewishness seriously involves a meaningful engagement of some kind with Jewish religion, the absence of which entails not secular Judaism in America (at least not at the statistical level—there are always exceptions) but disengagement.

A social scientific study is reliable to the extent that its results are replicable, internally consistent, and free from error. It is valid if it asks the right questions. I don’t doubt the Pew’s reliability, but I do have doubts as to its validity, at least in some respects.

Consider the question of denominational affiliation of American Jews. Respondents who identified as Jews by religion were asked with what denominational or other religious affiliations they identified. On this basis, Pew found that Orthodox Jews represented about 10 percent of the American Jewish community, Conservative Jews about 18 percent, and Reform Jews around 35 percent of all Jews surveyed. It is of more than passing interest that among Jews of no religion one percent also identified as Orthodox, six percent as Conservative, and 20 percent as Reform. So once again, the meaning of these categories remains tantalizingly open to question.

But does simply asking people about denominational affiliation get to their religious position within the Jewish community? Pew insists that most denominational shifts in American Jewry take place leftwards (Orthodox Jews becoming Conservative, Conservative becoming Reform) and makes no mention at all, for example, of the outreach efforts of the Chabad movement. Can one really paint an accurate picture of American Jewry in which Chabad does not appear? The number of independent Chabad centers in my own city of Atlanta has doubled and trebled over the past 15 years, not to mention their presence on over one hundred college campuses nationwide. Moreover some leaders of liberal Judaism are clearly nervous: There really is no other way to understand the odd claim by the Reform movement’s President Emeritus Rabbi Eric Yoffie that Chabad competes unfairly with liberal movements by placing insufficient religious demands upon the people who make use of its services.

Many Chabad institutions do not maintain formal membership rolls the way denominational synagogues do, and their membership tends to be fluid. Even people who frequently attend Chabad synagogues or events may also maintain membership in other movements. Yet, because they failed to ask directed and empirically informed questions to respondents on this score, Pew completely missed an important phenomenon in American Judaism. From my own ethnographic research, I can describe dozens of individuals who would never, on a survey, say that they are “Orthodox” or “Hasidic” or even “observant,” yet whose religious lives have been transformed in the past 10 years through participation in a local Chabad center alongside or in place of some other Jewish religious institution. Of all of the Pew study’s findings, I remain most skeptical that its denominational breakdowns present a valid account of American Jews’ religious lives.

And who, by the way, are the one percent of “Ultra-Orthodox” Jews who say that they have Christmas trees in their homes according to Pew? This may be a trivial question, a statistical glitch thrown up by a tiny sample, but suggests the skepticism that one must evince for any quantitative study that is not informed by interpretive qualitative research. When 30 percent of respondents tell Pew that one may be a Jew while believing in Jesus as the Messiah, do they mean that this is an acceptable Jewish belief or do they have in mind some version of the traditional Jewish legal opinion that “an Israelite, though he sins, remains an Israelite”? In the absence of any more fine-grained interpretive data, one can only guess.

Demographic surveys do not provide answers to social policy questions. The consensus of the heads of three liberal rabbinic seminaries at a recent round table on rabbinic education was that at least some of the liberal denominations (in particular the Conservative movement) are facing contraction over the next years while the proportion of Orthodox Jews in the Jewish population will probably rise. Referring to these statistics and to the rising alienation represented by the “Jews of no religion” category, the distinguished sociologist Steven M. Cohen (who served as an advisor for the Pew study) recently told a conference call of Jewish lay and professional leaders that he thought the demographic “sky was falling” on American Jews. This has led in some quarters to calls for radical programs like “secular conversion” or for allowing Conservative rabbis to perform intermarriages, presumably so that they can “reclaim” their lost market share. But these moves will prove counterproductive over the long term.

Indeed, one of the highlights of the Pew report is that for those Jews who choose to remain Jews, religion and peoplehood still cannot be separated. This is a good thing because it means that the old wellsprings of our creativity have not dried up, and we can still create communities of shared commitment—religious, cultural, and national—in which to wrestle with the significance of our heritage.

Is any of this surprising? Jews have learned to thrive under modern conditions and will learn to thrive in whatever comes next. Pew’s “A Portrait of Jewish Americans” suggests that religious commitments will continue to play a central and irreplaceable role. But this is not just because some people are “Jews by religion.” It is because Jewish faith itself begins with the paradoxical double promise God made to Abraham: “I will make of you a great nation . . . Through you all the families of the earth will be blessed.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On the Origins of Judaism: An Exchange

In our Winter 2024 issue, Malka Simkovich took a deep dive into Yonatan Adler’s thought-provoking new book, The Origins of Judaism: An Archeological-Historical Reappraisal. Her review explored Adler’s argument that Judaism as we know…

Tools of Hope: Finding Guidance from Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef

The Jewish muscle-memory that shapes our collective intuition, guides our response to calamity, and gives us hope that we will overcome this, too.

Letters, Fall 2020

The Coffee a Good Schmooze Demands, Unjustified Resentment, Whose True Voice?, and Yesterday's Today

Those Days Are Gone Forever

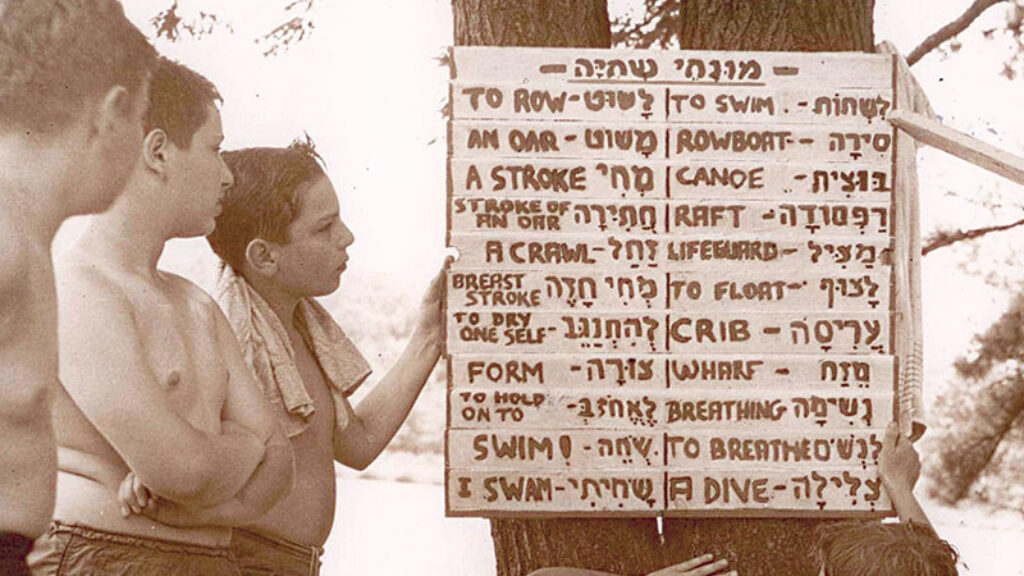

What, exactly, is camp spirit?

cantorwolberg

I have studied carefully this article and the pew article and have come to the following conclusion: in fantasy, everyone has the answer. In reality, nobody has the answer. Is it possible that in 1000 years historians will write that people once believed in a supernatural deity? And as they gradually progressed from polytheism to monotheism, it took some time to finally progress to atheism. For orthodox Jews, it took until the year 6000, when their promised Messiah never arrived. Somehow, they could not overcome that hurdle. However, the Christians needed more time before they realized the Trinity was man-made. Bottom line: everyone "knows" the truth but nobody has the truth.