Original Sins

The jacket of journalist John Judis’ new book features a photo of Harry Truman, placed so that only one of his eyes stares out from the cover. This is probably meant to signify the president’s failure to see clearly the morass into which his misguided Middle Eastern policy would ultimately lead the United States. But Truman is guilty, according to Judis, not only of a failure of perception. He deserves blame for lending his nation’s support to a movement that was most unworthy of it.

Genesis isn’t a rant, but it is a profoundly anti-Zionist book. Judis bitterly denounces Zionism as a “settler-colonialist” movement, employing an all-too-familiar term derived from what his colleague at The New Republic Leon Wieseltier rightfully terms “the foul diction of delegitimation, the old vocabulary of anti-Israel propaganda.” The movement’s fundamental and deplorable aim, he writes, was “to conquer and not merely live in Palestine.” (Judis dedicates his book to “my colleagues, past and present, at The New Republic,” not all of whom are likely to be touched by the gesture.)

With the Balfour Declaration, “the British and Zionists had conspired,” as Judis crudely puts it, “to screw the Arabs out of a country that by the prevailing standards of self-determination would have been theirs.” Judis doesn’t deny that Jews had a right to settle in Palestine, but he reiterates many times his conviction that they should have been prepared to live there as a minority among an Arab majority. The only Zionists for whom he has any real tolerance are those who eschewed the idea of Jewish sovereignty and sought nothing more than a binational state. The Zionists who upset him the most are those who succeeded in the past and are still succeeding in obtaining the support of the American government for their supposedly unjust political aims.

It is above all to counteract what Judis regards as these people’s nefarious influence that he has devoted years to writing his book. One can’t help but wonder, however, why it took him so long. His overview of the origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict and his account of America’s part in this history are virtually devoid of original research and, for the most part, go over well-trod ground, covered by many writers over the years, including me. Nor is there anything new in his attack on Zionism, which echoes the arguments (as well as the deceptions) of the movement’s many opponents over the past century. In fact, if Genesis were not the work of a staff writer and editor at The New Republic and put out by a major publisher, there would be no particular reason to pay any attention to it.

Some of the book’s many weaknesses are due to the fact that Judis doesn’t really possess the command of his subject that he pretends to have. His narrative is full of the sort of errors and omissions that abound in polemics disguised as history. Some of them are relatively minor, such as his drastic reduction of the number of First Aliyah settlers on hand in Palestine in 1884 from many hundreds to “about a score” and his postponement by two years of the date that Baron Edmund de Rothschild began extending financial assistance to these people. More revealing, perhaps, of his failure to do his homework is his statement that “Palestine was quiet during World War II.” While he knows that the “Stern Gang” staged terrorist attacks against the British during the war, he seems to be utterly unaware of the Irgun’s revolt in 1944 (or, for that matter, of any of its activities during the next couple of years, except for the bombing of the King David Hotel in 1946, which he mentions in passing, without explaining in any way).

If Menachem Begin altogether escapes Judis’ notice, his mentor, Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, comes in for more than his share of criticism. Jabotinsky’s defense in the 1920s of a militant “iron wall” policy, which rested on the assumption that “the Jews would succeed in gaining Palestine only by defeating, or intimidating, the Arabs militarily,” confirmed, he writes, “the Arab population’s worst fears about Zionist intentions.” What Judis fails to note is, to quote Walter Laqueur’s A History of Zionism, that “Jabotinsky wrote in his programme that in the Jewish state there would be ‘absolute equality’ between Jews and Arabs, that if one part of the population were destitute, the whole country would suffer.” (One suspects that Judis is aware of these things, for it is Laqueur himself who heads the list of people he thanks in his acknowledgments for supplying him with reading material.) While Judis pounces, when he can, on any reference on the part of a Zionist leader to the transfer of the Palestinian Arab population to some other territory, Judis makes no mention of the fact that Jabotinsky vociferously opposed any such notion.

It is Jabotinsky’s people that Judis blames, too, for the descent of Palestine into violence in 1929. In the midst of a year-long dispute over the Western Wall in Jerusalem, several hundred members of the Revisionist youth group “shouting ‘The wall is ours!’ and carrying the Zionist flag, marched to the mufti’s home, where they held a large demonstration. That set off a succession of Arab demonstrations that degenerated into large-scale riots.” What Judis conveniently neglects to describe fully, however, is the central role the owner of the house in question, the Grand Mufti, Hajj Ammin al-Husseini, had in stirring things up. He didn’t just convene international conferences, as Judis notes. Throughout the 1920s, he distributed The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and regularly taught hatred of the Jews. In 1929, as Efraim Karsh has shown, he incited a youth rally to unleash “a tidal wave of violence.” (Judis is consistent, one might note, in his protection of the Palestinian Arab leader’s soiled reputation, touching only very lightly on his later collaboration with the Nazis, which seems to be deplorable in his eyes mostly because his “identification with Hitler’s Germany had allowed these Zionists to reframe their own role in Palestine and on the world stage to avoid any taint of imperialism or settler colonialism.”)

Judis is scarcely any friendlier to the Zionists of the Left than he is to those of the Right. In his thoroughly tendentious overview of the movement’s formative years, the only Zionists who earn his commendation are those who restricted their goals to the establishment of a Jewish cultural center in Palestine and were content with “being a minority in a binational state.” He admiringly traces the efforts of Martin Buber, Judah Magnes, and others to implement a non-statist Zionism, up to the last possible minute—May of 1948. He acknowledges, however, that everyone except a handful of Arab intellectuals ignored what he himself describes as their utopian proposals. Only before the issuance of the Balfour Declaration in 1917, he concludes, was it at all likely that the ground could have been prepared for “a majority Arab state with a vibrant Jewish minority.” True, Judis cautiously notes, “Such a nation would not have been free of conflict.” And at that anyone with knowledge of the fate of religious minorities in the Arab world in the 20th century can only laugh. The notion that a Jewish minority could ever have enjoyed security in such a polity is entirely ludicrous.

After devoting Part I of his book to the depiction of political Zionism as an unjust cause, Judis briefly recounts in Part II the history of the Zionist movement in the United States up to the end of World War II. In Part III, which constitutes more than half of the book, he deals with the “Truman years,” during which, as he puts it, “the pattern of surrender to Israel and its supporters began.”

Judis’ narrative of this last period follows the same trajectory as my wife’s and my recent book A Safe Haven: Harry S. Truman and the Founding of Israel, which he credits with being “the latest and most complete blow-by-blow account of what happened” at that time. Yet I’m afraid that we see the same facts somewhat differently. We develop the story of how Truman came to accept the existence of a Jewish state in the making, while Judis writes of the tragedy he believes took place when Truman ignored those in the State Department who favored a more pro-Arab policy and yielded to Zionist pressure.

The greatest misdeed of the American Zionists, according to Judis, was their sabotaging of the so-called Morrison-Grady Plan. The outcome of joint British and American investigations and deliberations with regard to the Palestine problem, it called in July of 1946 for the division of Palestine into two partially self-governing provinces—one Jewish and one Arab—with a British-controlled central government. Jerusalem and the Negev would be under the direct jurisdiction of the British Mandatory power, which would maintain control over defense, foreign affairs, taxation, and immigration—following the admission of 100,000 Jewish wartime refugees into the country.

The Zionists rightfully noted that this plan gave them only 1,500 square miles under tight federal rule, less than what had been offered to them by the Peel Commission in 1937. President Truman, for his part, thought Morrison-Grady might solve the Palestine problem, but was quickly opposed by Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York and by James G. McDonald, the former League of Nations high commissioner for refugees, who told Truman if he accepted this plan, “you will be responsible for scrapping the Jewish interests in Palestine.” In the United States Senate, there was strong bipartisan opposition to the plan, led by Wagner and by “Mr. Republican,” Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio.

Judis again and again blames the Zionists for having thwarted American support for the Morrison-Grady plan. But how much would it have mattered if they had acted differently? The Arabs, for their part, not only rejected Morrison-Grady but refused to consider subsequent British proposals that were even more favorable to their position. When the British, at the beginning of 1947, “tilted markedly to the Arabs,” as Judis puts it, and presented a plan that would lead in five years to what would have been a unitary state under Arab majority rule, “the Arabs, who were unwilling to compromise even on 100,000 immigrants, also rejected it unconditionally.” They refused, in fact, even to enter into negotiations over the plan, since they refused to meet at that point with any Jews, from Palestine or anywhere else. It was their own leadership, no less than American Zionists, that stood in the way of their attainment of their goals.

Judis does lament the Palestinian Arabs’ failure to take advantage of “genuine concessions,” but he will not condemn them for it, for they were, in the end, holding out for what he believes was rightfully theirs: immediate and untrammeled sovereignty in their own land. Nor, in the final analysis, will he condemn Harry Truman for failing to create a binational or federated Palestine. He could only have done so, Judis says, “through credibly threatening and, if necessary, using an American-led force to impose an agreement upon the warring parties. And it might have taken years (as it has in the former Yugoslavia) to get the Jews and Arabs to accept their fates, and it still might not have worked.”

More surprisingly, Judis won’t even condemn the post-war Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion for being as resistant as he was to compromise. He was, after all, still leading the Zionist movement in the shadow of the Holocaust. While the Nazi defeat discredited political anti-Semitism in much of Europe and in the United States, that was by no means evident in 1946. The Jews, as far as Palestine’s Zionists were concerned, were still engaged in a war of survival. With these comments, Judis seems to be belatedly and inconsistently opening the door to a justification of political Zionism. But if so, he doesn’t open it very wide. However great the wrongs inflicted by Europeans and others on the Jews, he immediately insists, “the Zionists who came to Palestine to establish a state trampled on the rights of the Arabs who already lived there.”

To Judis, this is the wrong that is most in need of universal acknowledgment. Not the decades-long war of Israel’s enemies “to push the Jews into the sea” (or in its modern equivalent, to “liberate Palestine from the river to the sea”) but the Jews’ desire to have a state of their own in territory representing less than 0.02 percent of the land mass of the Arab Middle East. To atone for this wrong, Judis believes, one of the principal guilty parties, the United States, should change its overall orientation. “If America has tilted in the past toward Zionism and toward Israel, it is now time to redress that moral balance” by making sure that the Palestinians “get treated justly.”

But what does justice entail, in this case, in the eyes of a man who regards the very establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine as a profound injustice? Would enough justice be attained if a two-state solution were reached? Or does justice require, as some anti-Zionists and post-Zionists proclaim, the dissolution of the state of Israel and its replacement by a unitary state in all of Palestine as Judah Magnes once advocated? The last paragraphs of Judis’ final chapter highlight the problem of the Palestinian refugees. Does he think that justice entitles all of them to a “right of return”? Does he look forward to the day when they, in their millions, together with the Arabs currently living in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza will constitute the large majority of the population of the unitary state that will replace Israel?

Genesis does not contain Judis’ answers to these questions. In a piece published on the The New Republic website in January 2014, however, he is more forthcoming. If a “federated or binational Palestine” was “out of the question in 1946,” he writes, “it is even more so almost 70 years later. If there is a ‘one-state solution’ in Israel/Palestine, it is likely to be an authoritarian Jewish state compromising all of British Palestine. What remains possible, although enormously difficult to achieve, is the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel.” Thus, without ever acknowledging explicitly that a Jewish state has any real right to exist, Judis tacitly accepts Israel as a fixture on the scene. But he does so grudgingly. Indeed, in The New Republic piece he insists that Truman and his State Department were right to be apprehensive about the way things were unfolding in the late 1940s: “their underlying concern—that a Jewish state, established against the opposition of its neighbors, would prove destabilizing and a threat to America’s standing in the region—has been proven correct.”

Judis clearly regrets that a Jewish state was ever established. Whether Israel, in the course of its 65-year history, has any great achievements to its credit, or whether it has ever enhanced America’s position in the Middle East, are not questions of any real interest to him. What he wants above all is to see his own country make amends for America’s past support of Zionist settler-colonialism’s sinister project of migration to Palestine, launched “with a purpose of establishing a Jewish state that would rule the native Arab population.” He has now done his own little bit to make this happen by writing a book that often presses history out of shape and into the service of his aspirations.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

American Gods

One need not buy into the cultural importance of “Snapewives” to accept that the digital age is one in which individuals demand narratives, practices, and communities they find personally meaningful.

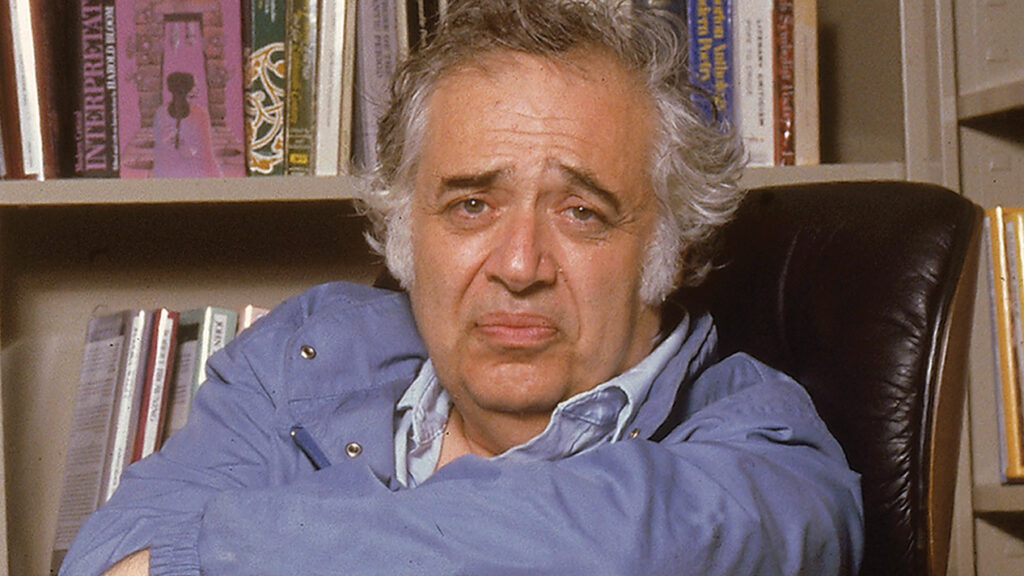

Remembering Harold Bloom

As Harold Bloom's student, I wanted to be transported to the heights of the literary sublime where he always seemed to reside, whatever the cost (it seemed considerable).

Sacrificial Speech

Just a few years after the publication of her Purity, Body, and Self in Early Rabbinic Literature, Mira Balberg has somehow managed to write another path-breaking work on another formidable and arcane section of rabbinic literature—sacrificial law.

What Is a Jew? The Answer of the Maccabees

In 1958, David Ben-Gurion sent a letter to fifty Jewish leaders around the world, asking, "Who is a Jew?" He had good political reasons to launch such an inquiry, and equally good reasons to expect answers or attempts at answers. Isaiah Berlin wrote back, and so did the Jewish scholar Alexander Altmann, the novelist S.Y. Agnon, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe, as well as many others. But Abba Hillel Silver, the prominent Reform rabbi and American Zionist leader who had represented the Jewish Agency before the United Nations a decade earlier, did not respond to Ben-Gurion's missive—not directly, anyhow.

pborregard

Poor scholarship due to reliance on "polemic disguised as history"... Or maybe a thorough assimilation of the output of an extensive disinformation campaign?

charles.hoffman.cpa

In his own snarky and hostile manner, the author does bring one very important fact of American-Jewish history to the forefront. After being shut out of the debate in 1930s over immigration and in the early 1940s over military policy, American Jewry finally forced its influence into national affairs by pressuring for the recognition of Israel.

Since then, Jews in the US have used their influence for their brethren overseas and in Israel. The rest of the world may dislike it; and the loony left my not appreciate it. But American Jewry is no longer afraid of its own shadow

dliecht

Ronald Radosh appears to be confused that one could accept existence of a national state as a given fact, yet openly acknowledge the moral ambiguities adhering to the founding and history of that state. Surely anyone who studies the early USA history would be well practiced in that particular balancing act. I myself live in "The Land of the Illini," though I am not an Illini and have no desire or intention of giving my little quarter acre back to the Illini. Furthermore, I would expect state protection were my property reoccupied by those who asserting an historical claim to it, even if that claim were easily defended on moral grounds. I love the USA, I am glad to live here and to raise up another generation here. Yet unquestionably its founding and early history is inextricable from a continuing pattern of land theft, knowing deception, murder and intentional genocide perpetrated against its Native inhabitants, even to the point of having elected its highest national leaders on the basis of their reputations as "Indian killers." We do no one a favor (ourselves least of all) by downplaying the facts of this history. We do even worse when we ascribe justification for our history to religious sources. We did what we did, we can't turn back the wheels of history, and so we have to live with it. My love of this land will always be tempered by the facts of our history. The analogy to the State of Israel is not perfect, but surely strong enough to bring it to attention.