Missing Menachem

In the Israeli elections of May 1977, Menachem Begin became the first person outside of the Labor movement to lead his party to victory. When the elections results were made public, Yitzhak Ben-Aharon spoke for the political establishment when he declared on television that, “If this is the will of the people, we have to replace the people.” Many in Israel perceived Begin, the longtime chairman of the Likud party, less as a political adversary than as a demon.

It was not only Israelis who saw him this way. In his new book, Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul, Daniel Gordis reminds us that Albert Einstein and Hannah Arendt (among others) signed a letter in The New York Times in 1948 that condemned Begin and branded him as a fascist. And that was relatively restrained. Ben-Gurion not only called him a “clown,” but wrote in 1963 that Begin reminded him of Hitler. When the Founding Father of the state ran someone down, it wasn’t merely a private opinion.

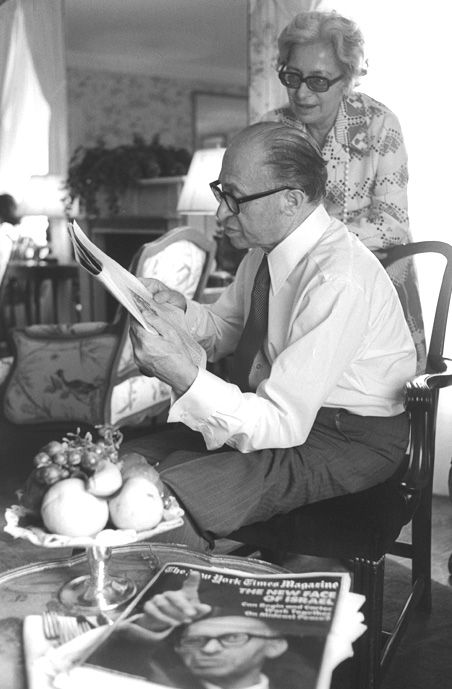

Twenty-one years after Begin’s death, Israelis’ attitudes toward him are altogether different. Daniel Gordis, to be sure, exaggerates a little when he declares in the introduction his new book that “Everyone, it seems, misses Menachem Begin.” But there is no doubt that today just about every camp finds something in Begin’s legacy with which to identify. In the pages of the liberal Ha’aretz, Begin’s respect for the judicial system and democracy is emphasized. Among conservatives, his devotion to the whole land of Israel is stressed; in the religious camp, it is his connection to Jewish tradition (in its Orthodox form) that is stressed. And most Israelis admire Begin’s extreme and entirely genuine modesty (when he left the office of prime minister it turned out that he didn’t even own an apartment to which he could return).

It’s no surprise that every camp has a different image of Begin. He was a unique and complicated man: He sought to initiate programs that would expand the borders of Israel, but, true to his liberal worldview, he opposed the military rule that Ben-Gurion imposed on the Arabs of Israel. Before the establishment of the state, he rejected the authority of the Palestinian Jewish community’s institutions and instructed the Irgun to engage in terrorist actions against the British. But when Ben-Gurion responded by launching an operation to break the strength of the Irgun (the so-called “Saison” crackdown) Begin prevented his men from retaliating. He invoked a hard-and-fast rule: “No civil war, ever.” As prime minister, Begin invited the free market economist Milton Friedman to advise him on transforming Israel’s socialist economy, but he retained a basically socialist outlook that stood in the way of implementing most of Friedman’s recommendations. Begin’s duality is one of the things that makes him such a riveting figure.

He was born in 1913 in Brisk, a typical Jewish town in Poland, and, under the influence of his father, Ze’ev Dov, he was captivated by the Zionist idea as a boy. Thanks to his rhetorical abilities, Begin advanced rapidly in the Revisionist movement, rising to the position of leader of the Betar youth group in Poland, which constituted the core of Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s supporters. Although he was a small man with a frail appearance, his speeches always broadcasted strength.

In 1939 Begin fled from Warsaw to Soviet-controlled Lithuania in fear of the Nazis, but at the end of 1940 he was accused of engaging in subversive Zionist activities and arrested by the NKVD (the Soviet secret police). Sentenced to eight years of imprisonment, he was liberated after several months so that he could enlist in General Anders’ Polish Army, which was formed to fight the Nazis. When he left his cell, he learned that the Nazis had murdered his mother, father, and older brother. Begin arrived in the Land of Israel in 1942 as a soldier in Anders’ Army. At the end of 1943, after his release from service, he was appointed commander of the Irgun. Even though he had no real military experience and was personally squeamish (he would always turn his head at circumcisions to avoid the sight of blood), he launched a violent revolt against the British in January 1944, and continued to fight them until they gave up control of Palestine. With the creation of the state in 1948, Begin dissolved the underground and founded the Herut party to oppose the Labor Zionist Mapai. Twenty-nine years later, when he finally succeeded in gaining power, it was due no less to the support he had garnered among immigrants from Muslim lands than to the Revisionists and Irgun veterans upon whom the party was built.

Contrary to expectations, Prime Minister Begin signed in 1979 the first peace accords between Israel and one of its neighbors, Egypt. In return for the agreement, Begin, who had fought for his entire life for the entire land of Israel, agreed to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and to uproot the settlements there. What was for him an immense sacrifice led to more than three decades of peace with the country that had been Israel’s most formidable foe.

In June of 1981 he was re-elected, after having instructed the Israeli Air Force to destroy Iraq’s nuclear reactor. A year later he sent the Israeli Army into Lebanon on a mission that developed into a bloody conflict, mired in difficulties. This was the first war to truly divide Israeli society. In August of 1983, in the middle of his term (and the war), Begin surprised everyone with his laconic announcement that “I cannot go on any longer.” From then until the day of his death, almost nine years later, the gifted speaker who had stirred the masses over and over again remained thunderously silent.

Daniel Gordis’ clearly written and engaging book tells Begin’s story well and, perhaps more importantly, makes a fine contribution to the study of his character. As he informs us in his introduction, “This book makes no attempt to offer itself as a definitive biography,” and certain critical episodes in Begin’s life are absent from it. Rather he seeks to answer the question, “What was the ‘magic’ of his draw?” His answer is a sympathetic one. “Despite the animosity that divided them almost all their working lives,” Gordis declares, “Ben-Gurion and Begin were both necessary elements of the creation of a Jewish state.” This sort of pluralism is not something one encounters every day, at least in Israel. Even those who do not share Gordis’ historical judgment must admit that it enables him to do justice to a subject, who in the course of his life was the target of countless negative and cruel descriptions.

The book’s central thesis is that Begin’s special appeal was bound up with the way in which he preserved the link between traditional Judaism and modern, national Judaism, that is to say Zionism. “For Begin,” he writes, “the manifest morality of the rabbinic tradition was no less obvious than the legitimacy of the Zionist movement.” Gordis explains that Begin acquired his worldview from his father, who strove to integrate the observance of certain religious traditions with his burning faith in the Zionist idea. “Menachem clearly inherited some of his father’s instincts. He once refused to take a Latin exam on Shabbat, to the amusement of his classmates.”

Gordis wisely emphasizes the simple but highly symbolic fact that has escaped the eyes of many observers: He was the only prime minister of Israel who did not attempt to sever his direct links to the diaspora by Hebraicizing his name.

Ariel Sharon’s original last name was Scheinermann. Golda Meir had been Golda Meyerson. But Menachem Begin did not change his name. His Jewish roots were the only roots that he needed or wanted; when called upon to testify before a commission of the Knesset toward the end of his life, and asked to state his name, he answered, simply, “Menachem ben Dov ve-Chasia Begin.” It was not an Israeli name, but a Jewish one. It was a reminder that Israel mattered only if the Jews mattered.

It was, indeed, by means of his emphasis on the link between religion and nationality that Begin enhanced his connection to the Jews from Muslim lands, whose impetus to migrate to Israel came from the national idea embodied in the Bible, the prayer book, and rabbinic texts, not Zionist thought. In large numbers they supported him, and he greatly strengthened their position in the country.

Gordis argues, correctly, that Begin’s positive attitude to traditional Judaism, which took shape in the diaspora, also determined his view of various issues that arose in the course of the country’s history. Thus, for example, in Chapter 8, “Say ‘No’ to Forgiveness,” he discusses Begin’s battle against the “reparations” agreement that Ben-Gurion arranged with West Germany at the beginning of the 1950s. The fight against the agreement, which called for a certain measure of forgiveness, or at least forgetting, of the Germans’ guilt in the Holocaust, in exchange for financial compensation, epitomizes Begin’s worldview. It was wrong to recognize Germany as a nation, he protested, when it was really nothing but “a pack of wolves whose fangs devoured and consumed our people.” If the Israeli government would be so wicked as to cut a deal with these animals, it would lose all “moral legitimacy.”

One could say that if Ben-Gurion focused on those who had been rescued, Begin focused on the victims. That is to say, Begin thought that the Holocaust showed that Israel really was a “people that shall dwell alone” and, therefore, wished that the memory of the wartime horrors would guide future generations of Israeli leaders. Ben-Gurion believed, on the contrary, that excessive preoccupation with the trauma of the Holocaust would complicate efforts on the part of the nation and its leadership to lead the life of a normal nation. It was Ben-Gurion, of course, who won the day in 1952. “During the debate, and afterward,” however, Begin “emerged as the defender of the Jewish soul of the Jewish state. He was redefined as the political voice for whom the dignity of Jewish memory and its inseparability from Jewish survival mattered more than anything else.”

Just how much it mattered can be seen, for instance, from the language Begin employed in the meetings leading up to Israel’s attack on the nuclear reactor in Iraq in 1981. Referring on one occasion to The Clock Overhead, a then well-known novel by an Auschwitz survivor, Begin described the danger Israel faced as “a giant clock” that “hangs above our head,” and “is ticking.” Gordis also highlights the opposition to the operation in Iraq, both within the military establishment and in the political realm, and notes that Begin demonstrated strong leadership when he refused to be deterred by the skeptics. “It was the principle that would be known as the Begin Doctrine, which would endure long after Begin himself was gone from the political arena.” He adds that Ehud Olmert’s decision in 2007 to destroy the nuclear reactor in Syria and the threats that Benjamin Netanyahu is now voicing about Iran’s nuclear program derive from Begin’s doctrine. This is true. But in this context one must also take note of the reasons that Netanyahu adduces in justification of his threats: the fear of another Holocaust. That is to say, the influence of Begin on today’s Israel can be seen not only in the discussion of action against Iran, but also in its underlying terms and motivation. The Holocaust and the traditional Jewish paradigm of persecution and redemption are still present in Israeli society.

Post-Begin Israel is a Jewish state influenced by Orthodox Judaism in a way that the socialist fathers of Zionism never anticipated. This also reflects one of the differences between Begin and the founder of Revisionist Zionism, Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky. The latter, who was born in cosmopolitan Odessa, was influenced by the liberal tradition and the heritage of the Russian Enlightenment and aspired to create a secular Hebrew state in which religion would be separated from the state. Begin, a small-town Jew who had been exposed to the romanticism of the Polish national movement, was much closer to the spirit of religious Zionism, even if he was not exactly Orthodox himself.

In Palestine, Begin succeeded in crowning himself as Jabotinsky’s heir. It is worth noting, however, that Jabotinsky’s son, Eri, argued that Begin altered the original Revisionist ideology, and consequently left the Herut movement in the 1950s. Gordis doesn’t deal with this altercation. He dwells only on the famous confrontation between Jabotinsky and Begin at the Betar conference in Warsaw in 1938. Begin argued on that occasion that Zionism had reached a new stage, “militant Zionism,” while Jabotinsky continued to believe that political collaboration with Great Britain would lead to the establishment of the national home. According to Gordis, Begin was correct to lead the Irgun into a fight with the British, for he helped to get them out of Palestine. This is, in my opinion, a claim that has much merit, but one that should not be made without reference to the other factors that induced the British to abandon the Mandate, including the pressure exerted on them by the United States government.

One ought to admire Gordis for making another claim, since it takes courage to put it forward. He argues that the famous bombing of the central offices of the British Mandatory government in Palestine at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in the summer of 1946, an action that cost more than 90 lives, made a decisive contribution to the departure of the British less than a year later, for it proved to them that the price of staying in Palestine was just too high.

This is a strong claim. Many historians have asked whether the Irgun could have achieved its aims by less bloody means. Moreover, the bombing took place at a time when the Haganah and the Irgun were working together within the (brief-lived) framework of a united Hebrew rebellion. Could the Irgun have avoided all of this killing? Did the Haganah also bear some responsibility for the bombing? These are not the sort of historical questions Gordis’ fine book addresses, but his affirmation of the utility of the bombing of the Kind David implicitly upholds an important historical assumption: Without a certain measure of tough-mindedness the Jews would never have attained their homeland. This is a lesson that remains relevant in our own day, like much else that is connected with the unique leadership of Menachem Begin.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Revealer Revealed

Earlier this year, an email announcement of a publication made its rounds among scholars of Jewish studies. Written in the flowery Hebrew of the Eastern European Jewish Enlightenment, the advertisement proclaimed that the work would “reveal all secrets.”

Starving for Zion

For Chaim Gans, the justification for nationalism in general, and Zionism in particular, lies in the human rights of the individual.

The Fire Now

"As horrific as the Holocaust was, it is firmly in the past. . . . Though I remain horrified by what happened, it is history. Contemporary antisemitism is not. It is about the present. It is what many people are doing, saying, and facing now," writes Deborah Lipstadt in her latest book.

Suspecting Esther

For Seymour Epstein, the Megillah depicts the cycle of passivity and overreaction that is endemic to the diaspora.

yisrael.medad

Shiloh aasks, but does not answer - "Did the Haganah also bear some responsibility for the bombing?". Of course it did.

a) the operation was authorized by the 'X-Committee' on May 15th.

b) the go-ahead authorization was delivered to Begin in a note signed by Moshe Sheh.

c) despite two requests for short postponments, which he never explained to Begin, Shen did not cancel the operation.

d) Yitzhak Sadeh of the Palmah actually requested only 15 minutes warning.

davidsfarkas

Was Begin's response to war reparations the Biblical, traditional one? I don't think so. When the Israelites left Egypt, they were ordered by God to take reprations in the form of plundering the country. Indeed, in my view, that the Torah had to emphasize this command to Moses, twice, subtly conveys the angst Moses may have felt. He may have personally felt, as Begin, that taking the repearations would be taking "blood money" for the slavery. But God - as Ben Gurion understood - knew that the money would be needed for the establishment of the state.

Ben Gurion, too, let us not forget, was also rooted in the Bible; he was just not as rooted as Begin was in Jewish tradition.