Singing Gentile Songs: A Ladino Memoir by Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi

Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi’s memoir of his life in 19th-century Salonica provides a rare and intimate glimpse into a lost Ottoman and Jewish world. Sa’adi was an accomplished singer and composer and a printer who helped to found modern Ladino print culture. He was also a rebel who accused the leaders of the Jewish community of being corrupt, abusive, and fanatical. In response, they excommunicated him—frequently, capriciously, and, in the end, definitively—though with imperfect success.

Sa’adi wrote the bulk of his memoir (the first ever known to be written in Ladino) between the years of 1881 and 1890, although he continued to add material until a year before his death, at the age of 83, in 1903. Although short excerpts have appeared in print over the years, it has not been published in its entirety until now. Sa’adi’s manuscript outlived the collapse of the empire in which it was conceived. It survived wars, a major fire, and the Holocaust, during which not only Jews but also Jewish texts and libraries were targeted by the Nazis for destruction. The document passed through four generations of Sa’adi’s family, traveling from Salonica to Paris, and from there to Rio de Janeiro. In 1977, a relative donated it to the Israel National Library in Jerusalem, where, by chance, it was discovered by Aron Rodrigue.

Sa’adi wrote the bulk of his memoir (the first ever known to be written in Ladino) between the years of 1881 and 1890, although he continued to add material until a year before his death, at the age of 83, in 1903. Although short excerpts have appeared in print over the years, it has not been published in its entirety until now. Sa’adi’s manuscript outlived the collapse of the empire in which it was conceived. It survived wars, a major fire, and the Holocaust, during which not only Jews but also Jewish texts and libraries were targeted by the Nazis for destruction. The document passed through four generations of Sa’adi’s family, traveling from Salonica to Paris, and from there to Rio de Janeiro. In 1977, a relative donated it to the Israel National Library in Jerusalem, where, by chance, it was discovered by Aron Rodrigue.

Sa’adi was a key figure in the world of Ladino letters and Ottoman Jewish society. Over his working life, he printed an enormous variety of texts, both religious and secular. His press also eventually produced the newspapers for which he became famous, including the Ladino La Epoka (1875-1911), his own editorial creation, and the French Le Journal de Salonique (1895-1911), of which he was the director, though he did not know French. (His sons ran the paper.)

Sa’adi prefaces his memoir: “My purpose in writing this story is to inform future generations how much times have changed within half a century.” Nowhere was this change more manifest than in the city he called home. Salonica in the 19th century was a thriving industrial and cultural center that served as a hinge between Europe and the Middle East. It had become the third largest port in the Ottoman Empire, connected to the main arteries of Europe’s railways (via Belgrade).

While the city was home to Jews, Muslims, and Christians, one was more likely to hear Ladino spoken in the streets than any other language. Salonica’s Jews, who made up more than half of its total population during Sa’adi’s lifetime, were crucial to its economic success. The majority of them worked as fishermen, porters, longshoremen, or factory workers in the city’s burgeoning industries. At the time Sa’adi composed his memoirs, Salonica was just beginning to witness many of the changes that came to define Sephardic modernity. He describes the Ottoman Jewish millet (religious community) whose leadership was still able to govern, tax, and legally try its own members when, in short, the Ottoman state granted the rabbinical authorities license to police the religious and social barriers of the Jewish community. Moreover, the Alliance Israélite Universelle (a French-Jewish communal organization that introduced modern schools across the Levant) had not yet gained the influence it would shortly acquire. The memoir describes a city, and a Jewish community, just beginning to tip over a colossal waterfall of change.

Sa’adi himself was an agent of this transformation. Because of his active involvement in attempts to reform communal institutions, his opposition to the rabbinic tax on kosher meat, and, not least, his insistence on singing Turkish songs at Jewish weddings, Sa’adi was constantly at odds with the traditionalist Jewish elite of Salonica. After innumerable skirmishes and short-term excommunications, which he describes with irony and anger throughout the memoir, the conflict came to a head. Sa’adi describes a trumped-up accusation that his elder son Hayyim (Kitapchi Hayyim) was seen smoking in a coffeehouse on the Sabbath. His heated defense of Hayyim led to a rabbinical writ of excommunication (cherem) against father and son alike. The pair were pursued through the streets by a large crowd and saved from physical harm only due to the intervention of a prominent Jewish philanthropist. Intended to last thirty-one years (he did not live to see its end), the cherem was the central trauma of Sa’adi’s life, and it ripples through nearly every page of his memoir. Ironically, La Epoka owes its existence, at least in part, to this excommunication, which prevented him from continuing to earn his living from printing religious books and performing at Jewish weddings.

Of special interest are Sa’adi’s discussions of the world of Ottoman music. He had learned his craft at the feet of an Ottoman music master while absorbing a different and yet parallel liturgical tradition from his Jewish music mentor. He describes his meetings with Muslim singers to rehearse traditional Ottoman and Hebrew songs; the creation of a choir consisting of both Muslims and Jews; the outrage caused by the introduction of that offensively noisy toy, the violin, to Jewish weddings; and, in the selection below, of the rabbinic wrath he incurred for “singing the songs of gentiles.”

And yet, despite Sa’adi’s biliousness, his memoir paints a rich, sometimes tender picture of Jewish life in Salonica. He describes a city so dense that firing a gun at a stray cat could shock a pregnant neighbor into labor (despite the fact that both mother and baby were fine, this act placed Sa’adi, the shooter, in yet another short-term cherem)—a city of hidden doors, myriad markets, thick with cafes and bars. Through Sa’adi’s memoir, we revisit the Ottoman Jewish world through local eyes.

The following excerpt of this memoir comes from the eighth chapter of Isaac Jerusalmi’s masterful translation entitled A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica: The Ladino Memoir of Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi, recently published by Stanford University Press. The book also contains a complete transliteration and a major glossary.

As I mentioned earlier, earnings from the business of printing were not enough. Therefore, I devoted myself to my singing career, first because at that time there was no one else to compete with me and, second, because I was well-acquainted with an impressive repertoire of Jewish liturgical poems, as well as Turkish songs and melodies passed on to me by both maestros. There was scarcely a celebration or a banquet where I was not invited to sing; especially at a time when it was not customary to have Turkish musical entertainment during celebrations, I, my younger brother, and a colleague had a virtual monopoly. Up to that time, music players and singers for celebrations or banquets were drawn from the group of the religious minyan who could sing a few popular songs for dancing. But as soon as the people learned to enjoy listening to Jewish liturgical music a la turka, those old music players rushed to the Rav h”r Shaul, reporting to him that “last night so-and-so attended such-and-such celebration and was singing some dirty Turkish songs!” Never missing a beat, the Rav h”r Shaul would send excommunication instructions directed at me. As for me, I was compelled to go and seek his forgiveness, not because I was afraid of his excommunication, but I did dread the lashes, if I did not seek his forgiveness.

This happened three times a week. By the fourth time I was uncertain that I could ever win, until the day came when he excommunicated me for what happened the previous night. Two hours later, an organizer, who was my namesake, came to invite me for that night. He was also an honorary beadle at the home of the Rav h”r Shaul who had three beadles, one of whom was ham Chelebon Mordoh, the excommunicator. My answer to this man, who invited me for that night’s celebration was, “It is scarcely two hours ago that the sinyor rav has sent me a hostile message.” He answered me, saying, “Please, do come tonight, and tomorrow you can work on two releases for the effort of one!” [quoting a Turkish phrase], “pay me for one, I’ll count it as two.” I accepted his challenge and joined him immediately. While the guests were arriving, I started a conversation with this organizer, also called ham Sa’adi a-Levi, hoping to find ways of escaping from the wrath of the sinyor rav. He answered, saying, “If you are not afraid of his excommunication, why do you keep going each time to seek his forgiveness?” My answer was, “The excommunication is not the reason why I ask his forgiveness; it is rather the fear that if I do not ask his forgiveness, he goes on with a foot beating [falaka], in keeping with the custom that the sinyor rav sent a memorandum to one of the gevirim [well-to-do people] who in turn dispatched two kavases [bodyguards] to pick up the culprit, enough to scare one to death.” Then he told me that when the sinyor rav proceeds with an excommunication, he never records who was excommunicated today and who was excommunicated yesterday, simply because he rarely limits himself to one or two a day. Instead, he issues excommunications for the slightest thing, up to twenty-five to thirty a day without his remembering those involved! Taking to heart this explanation, I henceforth quit going to the rav to beg for his forgiveness.

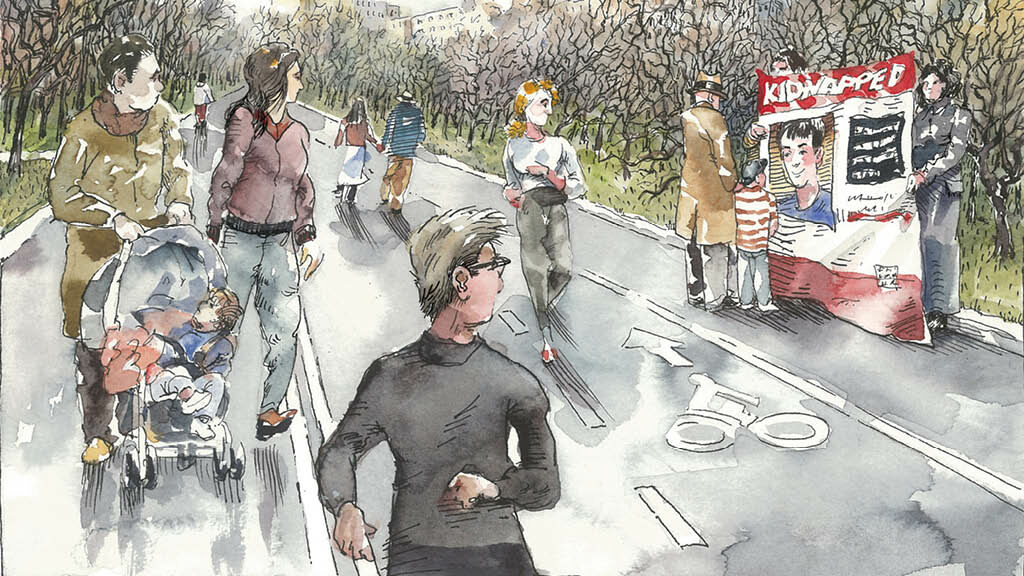

Once the rav was having a conversation with two or three talmide hahamim [religious scholars]. He was told about a new book [being published in my printing press] by a haham [sage, or rabbi] from Izmir which refuted the Shulhan Gavoa,whose author was his sinyor grandfather. He immediately asked to be shown some galley proofs to find out about the refutation. By coincidence, this also reminded him of my failure to go to him for his forgiveness after a number of excommunications. So now, he sent a memorandum to a gevir to issue an official note to the chief kavas to send him two kavases to pick up the culprit and administer two hundred lashes on his feet. He then hid the kavases in his kitchen, while at the same time called me, under the pretext of the refutations in this book concerning him. As I showed him the printed books, he yelled at me, saying, “You wicked man! Why didn’t you show up earlier for forgiveness after so many excommunications?” Wasting no time, he called ham Chelebon, saying, “Hand him over to the kavases.” Suddenly, I felt two iron arms, each one grabbing one of my limbs, as they dragged me on the way to the Vali‘s mansion. I screamed, but no one heard me. He, too, was screaming, “You, the accursed, this will teach you to sing songs of the gentiles!” They rolled me down the stairs, then up the stairs to the Fishermen’s Synagogue. As they climbed the last step, I was plotting my escape. When we reached the street, I could see that we were across from Chilibi Moshon Mizrahi’sfront door. As a way to free myself from them, I said to them [in Turkish], “Allah, why are you holding me as if I were a murderer? I haven’t killed anyone, I haven’t robbed anyone, I haven’t dishonored anyone, have mercy on me, and I will go wherever you want.”My plea worked; they let me walk freely with them until we reached Chilibi Moshon’s open door, when I raced like an eagle almost flying to the last floor, and I hid under a bed. Some kokonas [a mocking term for elderly, spoiled women] were sunning themselves on the veranda. At the sight of the kavases, they got up with their canes and their umbrellas and their chairs, running after the kavases, warning, “How dare you enter the home of a Franko?” [Jews of Italian extraction who typically were part of the upper eschelon’s of Jewish society in Salonica.]A mob of passersby and businessmen had already filled the courtyard. Word had been sent to Chilibi Moshon’s office; within five minutes the Fernandes brothersand their kavases were already on their way, but when they saw the unruly crowd, they didn’t know what to expect. In turn the kavases of the Fernandes brothers succeeded in throwing out these persecutors by force, vacating the premises and locking the doors. Then they wanted to know why this had happened. The kokonas told the chilibis [respected gentlemen] that a certain Sa’adi who participates in our celebrations with Murteza is hiding upstairs. I was called at once and asked about the reason for my escape. I answered, “Frankly, even I don’t know why they arrested me to take me to the pasha‘s mansion.” Insisting, they said, “Did you commit any crime?” In my defense I said, “No, I didn’t commit any crime, other than I was dragged from Rav h”r Shaul’s house to the governor’s mansion to be flogged, for singing in Turkish, which the sinyor rav has categorically banned. Singing is my livelihood, but he keeps excommunicating me: My only choice is to disobey him.” The chilibis understood that I was right and decided to go to the pasha‘s mansion for a satisfactory explanation. The pasha was flabbergasted to hear that the chief rabbi and the gevirim could dispatch someone to be flogged for singing in Turkish. He called the chief kavas and admonished him, “Don’t you ever dare accept an official note from the Jewish community without first showing it to me”; immediately, the pasha sent a note to the gevirim with the warning that henceforth all such matters should be channeled through him only. This freed me from beatings and excommunications.

This is how they managed fifty years ago. What are the thoughts of our contemporaries concerning the slavery we Jews endured under the heavy-handed tactics of our religious leaders?

A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica: The Ladino Memoir of Sa’adi Besalel A-Levi, Edited and with an Introduction by Aron Rodrigue and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Translation, Transliteration and Glossary by Isaac Jerusalmi.© 2012 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of Stanford University Press.

Suggested Reading

Hollywood and the Nazis

In their dealings with Germany in the 1930s, were Hollywood’s moguls just watching the bottom line or aiding the Third Reich’s PR machine?

Facing Faces

Nearly every morning since October 7, I open my phone and look at the faces of the war’s most recent victims. I gaze at these portraits fearfully, searching for a…

A “New History” and Old Facts

Fifty years after the conflict, Guy Laron’s The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East attempts to upend our understanding of the hostilities.

Missing Menachem

When Menachem Begin led the Likud to victory in 1977, Yitzhak Ben-Aharon spoke for many in the Israeli political establishment when he said that “if this is the will of the people, we have to replace the people.” Begin’s image has evolved, but he remains a contested figure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In