Even If the Ship Is Not Sinking

There have been many more studies of Israel’s early successes in integrating hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors and refugees from Muslim lands than of its failures. This is as it should be. That a poor and beleaguered new state could manage to absorb masses of new immigrants outnumbering its original population remains astonishing, despite the admitted flaws in the process.

But what about the out-and-out failures? By this I mean the significant numbers of Jews who took refuge in Israel after World War II, tried it out for a while, and then took flight again, sometimes maligning the country bitterly as they left. Usually confined to the very margins of the story, these people take center stage in Ori Yehudai’s unedifying narrative. What he tells us supplies some missing pieces of the overall picture, but it also raises some questions that he does not completely answer.

Yehudai does not dwell at length on the already well-documented hardships faced by new immigrants to Israel in the late 1940s and early 1950s—the dismal transit camps, the insufficient food allotments, the lack of work, the difficulty of learning Hebrew, the longing to rejoin relatives in the diaspora, and more.His story is about the people who abandoned Israel on account of them, heading back to Europe or North Africa or on to more promising lands, if they could.

“Between 1945 and 1967,” Yehudai notes at the outset, “nearly 192,000 Jews left Palestine and Israel, over 14 percent of the number of Jewish immigrants” who came in those years. Most of Leaving Zion is concerned, however, with the first half of that period, during which the total emigration was somewhat smaller than in the second half. Was that still a lot? Arieh Tartakower didn’t think so. In an October 1956 letter to an Israeli newspaper, the Hebrew University expert on Jewish migration argued that the rate of departure was low in comparison to the norm for other countries that have experienced heavy immigration. Tartakower was trying to quell what he saw at the time as unjustified “panic” over emigration from Israel. He was less than completely successful.

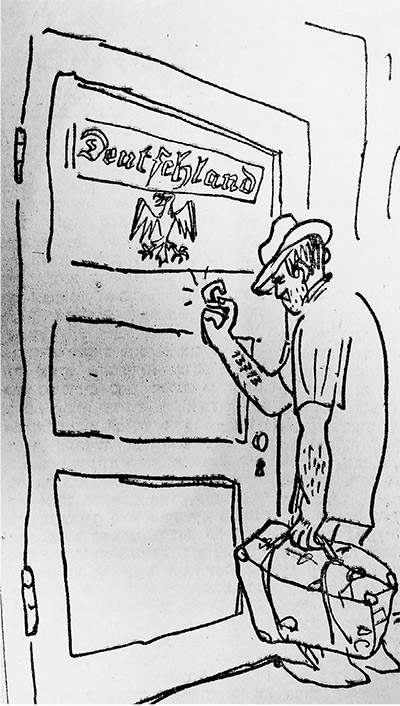

As Yehudai rightly observes, virtually any emigration at all from the Jewish state put in question Zionism’s claim to have resolved the Jewish problem once and for all. Nevertheless, Israel’s leaders could probably have taken in stride the limited emigration that occurred during the state’s early years had it not brought with it some especially painful embarrassment.Only a couple of years after the displaced persons (DP) camps in Germany had poured forth tens of thousands of immigrants, a few thousand newly minted but already disgruntled Israelis were sneaking back into the very same camps. They wanted another chance to start over and go to one of the rich, peaceful countries separated from Europe by at least one ocean, preferably the United States.

But first they needed the help of Jewish relief organizations, above all the Joint Distribution Committee, which had supported them before they went to Israel. The Joint, however, no longer had the kind of funds it had back in 1948, nor did it think that people who had previously been dispatched to Israel, which certainly counted as “a country of immigration,” deserved much help.

In June 1950, Samuel Haber, director of the Joint for Germany, explained to them the “facts of life”: they could get no jobs due to their illegal status; there was no possibility of organizing a camp for them to live in Germany as they could not register with the police or the Allied occupation authorities; there was no way to return their DP status; and the amount of assistance they could get from the Joint was insufficient to keep them alive.

But these disgruntled refugees from Israel wouldn’t take no for an answer, not from the Joint, the International Refugee Organization, or the now feeble and diminutive German Jewish community. Some of them managed to squeeze into the last remaining Jewish DP camp, Foehrenwald in Bavaria, “at the same time that the local authorities were endeavoring to close the camp and end the Jewish refugee presence in postwar Germany.”

Joint officials broke their own rules and provided the infiltrators with some small measure of support. They were often settled in living quarters that had been left by DPs who had recently emigrated from Foehrenwald. Soon they were joined by others, and by 1953 there were 3,500 of them (with more waiting in the wings). As the Germans struggled to deal with the situation through negotiations with the Joint and Israel, they succeeded in sealing off the camp—only to create a new problem. A couple of hundred Israeli “remigrants” took over the synagogue in nearby Munich. From this perch, they denounced Ben-Gurion and Israel as being worse than Hitler and the Nazis. Meanwhile, the Germans began to carry out threats to deport people from Foehrenwald to Israel. When the news of this action spread, “200 men, women and children of the general remigrant population left the camp, occupied the Joint’s office in Munich for two days, and declared a hunger strike until the deportation orders were revoked.” The Germans acquiesced and eventually defused the situation by facilitating the remigrants’ transportation to Brazil and other countries in the Americas. A few went back to Israel voluntarily.

In the aftermath of such outbursts, the Joint warned that “somebody in Israel must take greater responsibility for preventing such people to leave Israel who are an immediately potential burden on social agencies abroad and a political embarrassment to Israel.” The Jewish Agency suggested that that emigrants should not receive passports until they repaid “the costs involved in bringing them to Israel and maintaining them in Israeli immigrant camps.” This was opposed by the religious Zionist minister of welfare and religions, Moshe Shapira. These people, after all, weren’t acting out of malice; they simply couldn’t cut it in Israel.

Golda Meir (then minister of labor and still known as Myerson) was less forgiving. “I would go as far as demanding reimbursement for the costs of bringing them here,” she said. “Where is it written that a person would go hither and thither and the Jewish people would cover the expenses?” All of the migrants’ complaints reminded her of her own family’s experience in the United States half a century earlier.

“I remember that my father moved to America three years before the [rest of the] family immigrated. He was crying there and my mother was crying in Pinsk.” After the rest of the family moved to America, her “mother was crying there for years: the meat was not like the meat in Pinsk, and the milk was not like at home.” That experience had taught Myerson that the propensity to complain or give up was “a kind of a psychological problem of everyone coming to a new country. Surely it is hard.”

But the immigrants had to put up with it, for the good of the state and, indeed, for their own ultimate good. Making it harder for them to leave Israel was, she said, rather dubiously, not a violation of their individual freedom.

The restrictions on freedom of movement advocated by Meir and others evoked the opposition of defenders of civil liberties but werein the end adopted and seem to have had a major effect. “If until 1954 emigration was markedly characterized by the distress of stranded migrants in Europe and by the deep involvement of relief agencies in the migration process, after 1955 the number of dependent and needy emigrants diminished significantly,” even though the total emigration figures, which included people who were better off than the people who had been plaguing Germany, did not decline but remained high through the following decade.

The remigrants came not just from among the Ashkenazim. Already in the first days after Israel’s victory in the War of Independence there were recruits from North Africa who abandoned the country for points west. “A former soldier from Morocco who remigrated to France said that after completing his army service in Israel he had been unable to find a dwelling place and had been sleeping on the beach for several months before deciding to emigrate.” By November 1951, some of the Bene Israel who had arrived from India only two years earlier staged a sit-down protest in one of Tel Aviv’s main streets. They complained about everything from bad jobs to the absence of kosher food to racial discrimination, and demanded to be sent home. After they escalated their protest to a hunger strike, they got their way. Some of them eventually turned around and came back to Israel again, but that didn’t prevent some of their friends and family members from following in their earlier footsteps and returning to India.

In his accounts of all of these remigrants, Yehudai’s attitude is far closer to that of Moshe Shapira than that of Golda Meir. His dispassionate treatment of the subject reflects neither condemnation nor approbation of these men and women. While he provides a neutral overview of the intense government-orchestrated campaign against emigration in 1953 and its impact, his own description of the emigrants’ motives consistently demonstrates a sympathetic understanding of their difficult circumstances and respect for the decisions they reached.

“Was emigration a political act?” Yehudai asks, toward the end of his book. “As opposed to the ideological and political nature of the public debate on emigration, the migrants themselves were mostly driven by more prosaic issues like housing and employment difficulties, hardships in adjusting to the weather in Israel, career opportunities abroad, or the wish to reunite with relatives living in other countries.” This is no doubt true of the remigrants with whom he is mainly concerned. But how does their experience compare with that of the emigrants from the 1960s onward, when there was “an increase in the percentage of native-born, university graduates and professionals among the emigrating population”?

As an example of this tendency,

Yehudai might have chosen a man who plays a minor part in his narrative. Amos

Elon appears there “as a young reporter for Ha’aretz (who later became

an eminent Israeli writer)” who in 1956 agreed with Arieh Tartakower that there

was no need to panic over emigration but “shared the disapproving attitude

toward emigrants.” What Yehudai doesn’t mention (even in a footnote) is what

happened almost half a century

later. After having written, among many other things, one of the most

influential favorable portraits of his country, The Israelis (1971), and

Herzl (1975),

a sympathetic biography of its visionary founder,Elon sold his

apartment in Tel Aviv in 2004 and moved to Tuscany. He did so because he was

convinced that Zionism had exhausted itself and had become utterly disaffected

from what he saw as “a partly quasi-fascist and partly religious” State of

Israel.

Elon was, to be sure, technically a “remigrant,” but having settled with his parents in Tel Aviv in 1933 when he was only seven, he was to most intents and purposes a native. Instead of Elon, and understandably, Yehudai concentrates on Rogel Alpher, a much younger Ha’aretz columnist who voiced similar misgivings about the Zionist project in a 2014 column entitled “I Must Leave the Country”—though he didn’t, and still hasn’t. Alpher rekindled a decades-old debate that has never really flickered out about whether emigrants should be seen as despicable deserters (“from [ships] that are not sinking,” as the famed historian Yehuda Bauer observed) or as people who are just doing their own thing.

Yehudai himself does not see it as his task to intervene in this intense debate. He notes only that “the decision of Israeli Jews to live elsewhere still raises fundamental, even existential questions about the nature and future of Israeli society, about the relations between the state and its citizens, the meaning of patriotism, and the value of Jewish life in Israel versus life in the diaspora.” Personally, I am inclined to agree with Arieh Tartakower that this was not evidently correct with regard to the largely accidental and at best ambivalent remigrants of the 1950s to whom most of Yehudai’s book is devoted, but it is certainly true with regard to the native-born Israelis who followed in their footsteps or who are now thinking of doing so.

Suggested Reading

Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

Dubnov's magisterial autobiography, written while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. A new translation.

From the Great War to the Cold War

The facts of Hans Kohn’s life are so extraordinary that it almost seems as if the first half of one remarkable figure’s biography had been spliced together with another’s in the second part.

“Where They Have Burned Books, They Will End Up Burning People”

The surprising source for Heine’s prophetic remark that “where they have burned books, they will end up burning people” is a play about the fate of Muslims in Christian Spain.

Moses and Hellenism

In a provocative new work recently published in German, Bernd Witte proposes nothing less than an “alternative history of German culture,” as the subtitle of his finely wrought work of scholarship tells us. Moses and Homer: Greeks, Jews, Germans is a historical and cultural argument animated by powerful indignation. This history, he insists, has yet to be fully confronted.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In