From the Great War to the Cold War

That Hans Kohn regularly felt “unfulfilled” after his immigration to the United States in 1934, unable to make up for “lost years” and “constantly preoccupied with missed opportunities,” is a puzzle. For, as Adi Gordon shows in his fine new biography, Toward Nationalism’s End, by the time he reached America the 43-year-old Kohn had done a great deal more than the next guy.

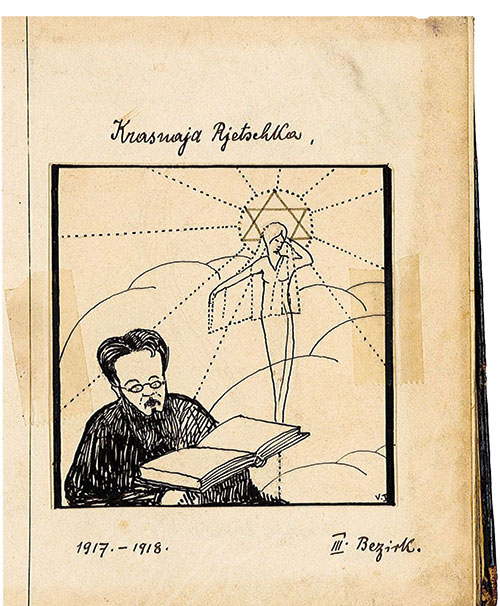

An active member of the fabled Zionist student association Bar Kokhba in pre–World War I Prague, Kohn had just completed his university courses when the war began. He eagerly joined the Austro-Hungarian infantry and was quickly captured by the Russians, in whose prisons he remained (despite a bold attempt to escape) for more than three years. Kohn didn’t waste his time in jail. Not only did he learn Russian, he also studied Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, and Italian, and significantly improved his French and English. “With utmost patience,” he wrote home at the time. “I have taught myself political economy (Nationalökonomie) and [about] the social problems.” (Along with their replies, his family was able to send him books.) When Kohn wasn’t studying, Gordon tells us that he “created a parallel Zionist college of sorts. This college, in which Kohn was the prominent lecturer, catered to several hundred POW-students.”

In May 1918, the Siberian prison in which Kohn was interred came under the control of the Czech Legion, a force composed of captured Czechs and Slovaks who had switched sides and continued, after the Russian Revolution, to fight alongside their former captors against the Bolsheviks. Still a Czech prisoner in 1919, Kohn helped to establish a socialist collective consisting of 189 Zionist inmates that went by the Hebrew name of Nemala (ant). Before long, however, the Czech Legion released him, and he became not only a citizen of Czechoslovakia but one of its employees, a deputy librarian at the Legion’s headquarters in far-flung Irkutsk—and an editor of a Russian-language Zionist newspaper on the side.

Finally out of Russia, in 1920, Kohn became a nationalist activist on a larger stage. For a year and a half he worked for the Committee of Delegations that represented Jewish interests at the Paris Peace Conference. He then moved to London, to work for the Zionist Keren Hayesod (Foundation Fund), where he replaced none other than Vladimir Jabotinsky as the head of the press and propaganda section.

In 1925, together with the rest of the Fund’s main office, Kohn moved to Jerusalem. He “never intended,” though, as Gordon tells us, “to become a full-time Zionist functionary.” In the ensuing years, Kohn wrote prolifically on current events for German and Hebrew newspapers, and published books on the history of Zionism and Jewish political thought, including a 400-page biography of his mentor Martin Buber. His even longer A History of Nationalism in the East “analyzed nationalism between Egypt in the West and India in the East, with regional chapters on Turkish, Persian, Afghani, and Arab” nationalist movements. The book earned accolades not only in Germany, where it was published, but from both the Times Literary Supplement in Great Britain and Foreign Affairs in the United States.

Quite apart from—and in some respects at odds with—his official Zionist work in Palestine, Kohn played a key role in Brit Shalom, the famous Jerusalem-based circle of Central European intellectuals, including Gershom Scholem, Hugo Bergmann, Martin Buber, and others, who favored the establishment of a binational state rather than a Jewish one. Brit Shalom’s opposition to Jewish rule over Arabs was not, however, quite enough for Kohn, and he pressed in 1925 and 1926, unsuccessfully, for the association to take a more forceful and public stance. At the same time, he became an active member of the War Resisters’ International, the Netherlands-based pacifist organization. This was an unstable mix of loyalties for a man living in a highly combustible environment, especially when the inevitable explosion took place, as it did in the riots of 1929. Convinced by the Arab attacks on the Jews that Zionist settlement in Palestine could be continued only through an unjustifiable recourse to bayonets, Kohn resigned from his position at Keren Hayesod and soon made preparations to leave the country.

In November 1933 Kohn finally found an academic post in the United States. If he still felt unfulfilled, even after Smith College hired him (following what seems to have been a near miss at Yale), it was because he had had to sever his ties with a movement to which he had devoted decades of his life and a land he still loved. His malaise was compounded by Hitler’s rise to power and the fact that he now found himself in a country that he had long regarded, in Gordon’s words, “as a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah.” Yet it was, he believed, unlike Palestine, a place where there was still room for hope.

Kohn’s grudging and qualified approbation of the United States eventually turned into a kind of American patriotism. The former socialist became a liberal and a defender of capitalism, and his pacifism gave way, in the face of Nazism, to an embrace of “the use of force as part of America’s responsibility” to protect the world from totalitarianism. Together with such luminaries as Thomas Mann, Reinhold Niebuhr, Eric Voegelin, and Lewis Mumford he battled American isolationists, right up to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Kohn continued to publish voluminously both during the war and after it. His most enduring work, as Gordon rightly notes, was his The Idea of Nationalism (1944), which consisted, as Gordon writes, of “almost 600 pages of deftly argued and deeply researched engaging historical analysis, followed by an additional 150 pages of eye-opening notes on sources in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, German, Italian, Dutch, Polish, Czech, and other languages.” For a generation, this book remained, according to Gordon, “the gold standard” in nationalism studies, noted above all for its famous and highly influential distinction between the

reason-based and inclusive “civic nationalism of the West,” which Kohn admired, and the myth-laden and combative “ethnic nationalism of the East,” which he deplored.

The Zionism to which he once adhered clearly fell into the latter category for Kohn, and he continued to write critically about it and to lobby actively against it. Among other things, he starred at the first annual conference of the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism in 1945 and sought, the following year, “to keep the American Jewish Committee from becoming pro-Zionist in the wake of the Holocaust.” In May 1949, two days after Israel was admitted into the United Nations,

Kohn packed up all the Zionist documents he had been collecting over the years: rare materials from Bar Kochba, unique documents of his Zionist activity as a prisoner of war, protocols of the Brith Shalom Association, and his extensive personal correspondence with Martin Buber and others. He sent the materials to the library of Hebrew Union College, the reform Jewish seminary. In his revealing letter to the college’s president, Kohn explained why he had donated the collection to that institution . . . Kohn wanted the documents to be “accessible in a library which is connected with the problems of Jewish history and of the Jewish ethos, and yet will undoubtedly maintain the standards of the American liberal tradition.”

When he gave these materials away, Kohn expressed the hope that they would be of interest to future historians of Zionism. But he also hinted at the possibility of a better future: “Who knows,” he wrote, “whether after some decades, some young Jews, doubtful about the values of nationalism and of statehood, might not find comfort in the doubts and struggles of a past generation, even in its (perhaps temporary) defeat.”

In the same year that he got rid of his Zionist library, Kohn moved from Smith to the City University of New York, where he taught until his mandatory retirement in 1962, after which he spent eight years rotating among American and German universities. He never stopped writing big books on subjects ranging from pan-Slavism to American nationalism. When he wasn’t ensconced in his study or a classroom, Kohn fought (in print and in think tanks) in the Cold War, which he regarded for most of its duration as a struggle against an effort “to destroy or undermine Western Civilization and strength.” If he made a singular contribution to this ideological battle, it was in showing the ways in which the Soviet Union’s purportedly “panhuman” ideals constituted a thin disguise for a pan-Slavic imperialism that pre-existed the communist regime.

Kohn’s work at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in the 1950s brought him together with then–Harvard professor Henry Kissinger to organize a conference that focused on “the moral and intellectual matrix out of which the North Atlantic community can grow.” But by the late 1960s disillusioned by the Vietnam War, Kohn ceased—in private, at any rate—to idealize the United States. After Kohn’s death in 1971, the Israeli professor of philosophy Hugo Bergmann, his lifelong friend, wrote in his diary of “Hans Kohn’s disappointment with president [Lyndon B.] Johnson and his politics. The American air force demanded the war against China. This shattered the ideals of Hans.”

The facts of Kohn’s life are so extraordinary that it almost seems as if the first half of one remarkable figure’s biography had been spliced together with another’s in the second part. The later years of Kohn’s life are reminiscent of those of some other European-born transplants who didn’t quite take to the soil of Palestine or Israel and ended up as leading figures in American academia, people like the philosopher Hans Jonas, in Kohn’s day, or, more recently, Daniel Kahneman or Saul Friedländer. But there is one major difference: None of these people, however critical of the Jewish State he became, ever turned his back on Israel the way Kohn did. He never even went back to visit.

Adi Gordon’s biography is excellent, though it doesn’t quite tell us everything we might want to know about Kohn’s singular path through life. There is, for instance, almost nothing in it about Kohn’s wife and only the briefest reference to his affairs with other women (which he discussed, Gordon tells us, quite candidly in his diaries). But there is plenty in Toward Nationalism’s End to enable us to make sense of Kohn’s initial attraction to what he eventually termed “ethnic nationalism,” his eventual repudiation of it, and his adoption—but only, in the final analysis, as a means to an end—of American “civic nationalism.”

The middle-class family into which Kohn was born in Prague was, by his own description, a highly assimilated one, and he had only a minimal Jewish upbringing, which may not have included any religious education at all. Like his friends from similar backgrounds in Bar Kokhba, Kohn was in search of something that the older generation had lost. For these young people, Gordon writes, the Jewish Question “was the personal one, grounded not in antisemitism and persecution but rather in an inescapable sense of emptiness, fragmentation, and inauthenticity.” Zionism attracted them because it had “the allure of primordiality.” Instructed by the then-young and charismatic philosopher Martin Buber, they initially hoped for the “transformation of the diasporic Jew (Golusjude) into an elemental Jew (Urjude)” through his return to “the homeland of his blood.” Many of the Bar Kokhba Zionists, including Kohn, soon began to question the absolute necessity of a return to the Jews’ ancestral soil in order to effect the desired transformation of the people. But they never ceased to affirm “a Jewish oriental primordiality grounded in the blood” that led them to reject “the claims of a singular occidental modernity, which they saw as threatening Judaism.”

The Judaism of Kohn and his comrades was by no means a traditional one. They wanted, in Hugo Bergmann’s words, to “rejuvenate fossilized Judaism,” but precisely what that meant to them before 1914 is not at all clear from either their own writings or Gordon’s analysis of them. In the case of Kohn, in particular, it was only in a letter that he sent in 1917 from his Siberian prison to his friends in Bar Kokhba that he began to spell out his fundamental convictions. Ahad Ha-Am, he wrote, was right: “justice is Judaism’s primary trait” and therefore also the “yardstick” by which Zionism has to be measured.

By 1919, after the war had ended and he had witnessed first-hand the deleterious effects of colonialism in the eastern parts of Russia, Kohn had decided what constituted the requirements of justice, and was prepared to articulate what “would remain the hallmark of his theory of nationalism.” He distinguished

between the benign and malignant: between true nationalism, on the one hand, and its degeneration into the ideology of the nation-state, on the other hand. Whereas he still saw in nationalism noble qualities and functions that had to be protected, he now believed that the ideology of the nation-state was inherently destructive and needed to be challenged.

If the Zionist movement were to take the shape of a true nationalism, it would thus have to spurn statist ambitions and focus on the development of a Jewish homeland that did not act “like a ‘nation-state’ (Staatsvolk) toward the Arabs” of Palestine, who constituted, after all, the large majority of the country’s population at the time. While still stuck in Siberia, Kohn issued what was “probably the first clear Zionist call for a multinational —or, rather, a binational—state in Palestine.” Only by this means, he believed, could Zionism uphold Judaism’s basic principle of justice and fulfill “the Jewish messianic mission.”

Over the next decade, Kohn tried to anchor his world view more thoroughly in Jewish tradition. In his 1924 The Political Idea of Judaism, which clearly echoes Hermann Cohen’s Religion of Reason: Out of the Sources of Judaism, Kohn made selective use of traditional texts to depict Judaism as a blend of “the idea of human unity and that of political justice.” What bound the Jews together and characterized them was now, for him, no longer blood and land but ideals, for which Palestine would be the testing ground. As he put it in an interview published in the London Jewish Chronicle in 1925, “in reestablishing their nationhood on the soil where their original conceptions of life were evolved,” the Jews “should not create a state like all other states . . . Palestine must become Jewish, not by imposing Jewish nationality upon any other race, but as a unifying entity among the peoples according to the ideas of Justice and brotherhood and humanity, which the highest Jewish thought [has] evolved.” When Kohn finally concluded that Zionism was failing the test, he too was done with it.

From this time on, Kohn was less inclined to focus on the highest Jewish thought than on what he considered to be the lowest, which he termed “primitive Judaism,” increasingly identifying it with “racism and tribal ethno-nationalism.” He sometimes even contrasted this form of Judaism unfavorably with the more universalistic Christian religion. In 1939, of all years, he “had no qualms about stating, ‘It is an historical irony that Hitler today is leading the German people back to the attitude of primitive Judaism.’” The humanist values that Kohn had once sought to locate or at least to situate within the Jewish realm he now understood to be rooted in the philosophy that he had rejected when he first turned, as a youth, to Zionism: liberalism.

It was only as a vehicle for the implementation of liberalism, or what he deemed “the concept of political liberty and the rights of man,” that Kohn endorsed what he believed to be the reason-based, contractual, and ethnically neutral “civic nationalism” that emerged in America, in particular. “Through the Western idea of nationalism,” he came to believe, “in the end all people will share ‘the faith in the oneness of humanity and the ultimate value of the individual.’” And thus, in the very end, there will be no need for separate nation-states at all. In the meantime, however, through World War II and the Cold War that followed, there were totalitarian threats that had to be met, and the drawbacks of even the best sorts of nation-states—including their unfortunate reliance on military force—had to be taken in stride. That’s what Kohn believed, until Vietnam, at any rate.

Adi Gordon is an Israeli scholar teaching at Amherst College, not far from Smith, where Hans Kohn once taught. He is also, it seems, one of those young Jews of a later generation, anticipated by Kohn, who has had his doubts about the values of nationalism and statehood, and has plunged into the papers Kohn donated to the Hebrew Union College in search of illumination. Gordon certainly gives Kohn his due, but he has not become his disciple. He criticizes him, on occasion, for such lapses as allowing his “Cold War idealism” to blind him to America’s faults and permitting his preoccupation with the Palestinian refugee problem to keep him from focusing on other, larger refugee issues, including “those in India, Pakistan, and Korea, to say nothing of the Soviet bloc.” He rightly dismisses some of Kohn’s works, including The Political Idea of Judaism, as “unpersuasive, half-baked countermyths,” and he never endorses his binationalist ideas.

Gordon does, however, regard Kohn as a useful intellectual resource. “Writing about Kohn,” he tells us, at the very end of his book,

forced me to think anew about the ideologies of my place and time, both as an Israeli and as someone who grew up during the Cold War . . . Furthermore, even if many of Kohn’s formulas have not stood the test of time, the questions he raised persist. His Sisyphean struggle with nationalism is now ours.

Hans Kohn deserves to be remembered as an outstanding member of an astonishing group of Central and Eastern European–born Jewish historians and political theorists who wrote extensively and penetratingly about nationalism and played significant parts in the histories of a variety of different national movements. His binary distinction between civic and ethnic nationalism was a key development in the study of nationalism and remains helpful, even if contemporary scholars focus more on its deficiencies than its utility. But I doubt that a return to Kohn’s writings or a recollection of his career will help us now, as Jews. This is, in part, because I am disinclined to believe that anyone who has separated himself from the community in the way that Kohn did can remain relevant. It’s not just that he turned against Zionism; he rejected Judaism and Jewishness altogether. In the end, as Gordon observes, Kohn “described Jewishness as devoid of any intrinsic value, as something merely to be tolerated: ‘There is no reason to be proud of being a Jew or a Christian or a Turk.’” In this connection, it’s also worth remembering that, as Brian Smollett has pointed out, Kohn brought up his son Immanuel (named after Kant) “in the New England establishment with little to no Jewish context or education,” just as he himself had been raised in Prague.

It is, in the end, impossible to see what Kohn has to contribute to ongoing reconsiderations of Zionism that we aren’t regularly hearing from other uncompromising opponents of ethnic nationalism and defenders of the wholly impractical idea of a binational Jewish-Arab state. Nor can we hope to hear anything helpful about being American Jews in the 21st century from someone who had no qualms at all about the complete absorption of the American Jewish community into the “melting pot.” For all of his experience and accomplishments (not least during the Cold War), Hans Kohn is one of those extraordinary figures whom we can safely leave behind us.

Suggested Reading

Tragedy and Comedy in Black and White

Lately it seems to be the season of haredim on screen. Sarah Rindner's immersion in this very particular oeuvre began with Shtisel, the 2013 runaway hit Israeli TV series, which depicts a haredi family in Jerusalem in all of its complicated, charming dysfunction.

Letters, Spring 2023

Cliff-Hangers When I first read Hillel Halkin’s assertion in “On That Distant Day” (Winter 2023) that “for years now, Israel has seemed to me like a man sleepwalking toward a cliff” and “now we’ve fallen from it,” I thought it was excessive, though I shared his concerns about the Likud’s coalition partners (Zionist theocrats, anti-Zionist free-riders). Writing now, in the…

The Genius of Bernard-Henri Lévy

Bernard-Henri Lévy's amour propre, while immense, does not quite extend to regarding his life as exemplary in its Jewishness, nor to tying all of his political actions to Judaism.

With Interest

Have the Jews been capitalism's best friends or worst enemies, or both?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In