Wishful Republic

As it did more than a century ago for Theodor Herzl, in his futuristic novel Old-New Land, Haifa symbolizes something new and fresh for Omri Boehm. But there the resemblance ends. Herzl envisioned a hypermodern city at the heart of a newly built Jewish society; Boehm sees it as a promising model for a binational federation:

In Haifa, a true experiment in civil living is going on. In Haifa’s hospitals, among them some of the best in the country, Arab and Jewish doctors work together treating the north’s heavily mixed population. Here Arab and Jewish patients lie side by side. At Haifa University, more than any other university in Israel, a program of binational, bilingual research, and higher education is actually conceivable, and an Arabic-language Israeli theatre, Al-Midan, already operates in the city.

I myself know Haifa University well. It’s where I earned my BA and my PhD. During my undergraduate years, I lived near Masada Street, the bustling heart of Jewish-Arab coexistence in the city, with its always-crowded Jewish and Arab coffeehouses, restaurants, and art and music venues. To me, too, Haifa once seemed to be the birthplace of a future revolution. I still felt that way when I started my dissertation on Judah Magnes, the American-born president of the Hebrew University who was, from the 1920s through the 1940s, one of the most ardent advocates for the creation of a binational state in Palestine. Had Omri Boehm published his book a decade ago, I would have welcomed it enthusiastically. Now, however, I cannot do so. Binationalism, I have come to think, wasn’t a good idea before 1948, and it isn’t now either.

An Israeli who grew up in the country’s north, not far from Haifa, and now teaches at the New School for Social Research, Boehm has written a slim book in which he presents Haifa as a model for what Israel as a whole could become: a binational federation incorporating all of the people living between the Jordan and the Mediterranean. This federation would include two less-than-independent states, Israel and Palestine, separated by the 1967 Green Line and governed by a joint constitution securing basic human rights and liberties and maintaining the separation of church and state. This constitution would recognize the right of return for both Jews to Israel and Palestinians to Palestine, with each state able to naturalize its own immigrants, subject to regulation by a joint steering committee. All citizens of each state would have the right to travel, work, buy land, and live in the whole territory of the federation, and a steering council would govern common security interests.

This is admittedly just a quick sketch of what is itself a somewhat sketchy proposal. Boehm is far less interested in fleshing out his plan than in providing a justification for it. It is not just the shining example of Haifa but what he perceives to be the collapse of the option of a two-state solution on account of the irreversible expansion of Jewish settlement in the West Bank. The current state of affairs is, he believes, ethically unsustainable and will only result in Israel’s plunging more deeply into moral degradation, expulsions, and “ethnic cleansing.”

Still, even if it were completely confined to its pre-1967 borders, Boehm would find the existence of a Jewish state objectionable. As he makes clear at the very beginning of his book, he does not believe that it is possible for a state to be both Jewish and a liberal democracy. In his proposed solution, “within each state, each of the peoples, the Jews and the Palestinians, will exercise cultural and national self-determination.” That is to say that even within the Israel side of the federation, Jewish nationalism will receive no preference.

Many writers have sought in recent years to reclaim the heritage of Magnes and the other binationalists. They have reminded us of Brit Shalom, an organization founded in 1925 to “pave the way towards an understanding between Jews and Arabs, towards coexistence in Palestine based on full equality of the political rights of two nations with broad autonomy.” They have likewise celebrated the Ichud, founded by Magnes and Martin Buber, which continued to advocate for a binational solution in the 1940s. Supporters of binationalism included academic faculty from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Kedma Mizracha (“Forward to the East,” a group encouraging familiarity with and ties to “the Orient”), the Marxist youth and kibbutz movements of HaShomer HaTza’ir, and Jewish American circles, including some of the leaders of Hadassah.

Curiously enough, Boehm sidesteps any discussion of these people and seeks to legitimate binationalism by focusing instead on the degree to which the more mainstream leaders of Zionism, from Herzl to Jabotinsky and Ben-Gurion, were themselves inclined toward it. By his account, the Founding Fathers of Zionism were committed to national self-determination but nevertheless eschewed the idea of Jewish sovereignty until very late in the day. And it is their binationalism, which “represents a type of politics that was a matter of consensus,” that can and ought to be rehabilitated. Here Boehm relies very heavily on Dmitry Shumsky’s analysis of important Zionist thinkers in his recent Beyond the Nation-State.

I think he would have done better to focus on Israeli historian Yosef Gorny’s 2006 book From Binational Society to Jewish State, in which Gorny shows that the binationalist proposals floated by Jabotinsky, Ben-Gurion, and others, mostly structured around some form of federation, were all designed to meet the political need of the hour, to placate the opponents of Zionism, or to preempt British attempts to promote some undesirable forms of political arrangements for Palestine. Jabotinsky, Gorny argues, believed in the logic of the binational scheme but doubted its applicability. He nevertheless thought that the Zionist Executive should prepare an alternative plan in case the British government or political circumstances forced the Zionists to negotiate a comprehensive understanding with the Arabs. Indeed, after his resignation from the Zionist Executive in 1923, Jabotinsky retracted his support of binationalism, stating that he was no longer an enthusiast for an Arab-Hebrew federation.

Gorny acknowledged the possibility that Ben-Gurion’s favorable remarks on binationalism masked his real political intentions:

The qualities of moralistic optimist and realistic statesman were inseparably integrated in Ben-Gurion’s personality. His Utopian yearnings were short-lived. . . . His cold political calculus, in contrast, coupled with an element of Machiavellianism, accompanied him throughout his lengthy career as a leader.

This is evident from his dealings with Judah Magnes. When, in December 1929, Magnes published his binational platform “Like All the Nations?” Ben-Gurion was keen to avoid a confrontation with Magnes’s American supporters and warned future Israeli president Chaim Weizmann off as well. Instead, he proposed that Labor Zionism leader Berl Katznelson meet with Magnes frequently to “prevent him from taking destructive measures.” Ben-Gurion reached out to Magnes for assistance after his meeting with Arab nationalist and politician Musa Alami in 1934, and Magnes later organized further meetings with Arab leaders. Yet following the outbreak of the Arab rebellion in 1936, Ben-Gurion severed his ties with Magnes. Reinstating Jabotinsky and Ben-Gurion as supporters of binationalism is, then, a stretch.

Besides, there never was any Arab support for this option. The episodes of Brit Shalom and later Ichud actually represented nothing more than internal Jewish discussions of the moral ramifications of the so-called Arab Question. Palestinian partners were few and their clout minimal. It is, of course, in many ways quite understandable that the Palestinians, as the majority in the land, felt no need to concede their control over the country to the people they perceived to be intruders. Magnes, however, never fully understood this.

In One Palestine, Complete, Tom Segev describes Magnes’s meeting with the Palestinian Christian intellectual Khalil al-Sakakini at the Shepherd Hotel in Jerusalem during World War II. Magnes was convinced that the Christians in Palestine were leaning toward political extremism because they were an unrepresented minority that feared the Muslim majority; he maintained that they could evade this danger by cooperating with the Yishuv and accepting binationalism. “Let us speak openly, Doctor,” responded al-Sakakini, and told him a tale about a donkey. A man who was riding his donkey saw another man walking and invited him to ride together. The second man climbed on the donkey and commented, “How fast your donkey is!” They rode on, and the stranger observed, “How fast our donkey is!” The donkey’s owner then said, “Get down!” and the other man asked “Why?” The owner replied, “I’m afraid that soon you’ll say, ‘How fast my donkey is!’”

Among Arab nationalists, things never changed. Even as Boehm insists on reading Menachem Begin’s 1978 “autonomy plan” as a genuine support of binationalism, and not as a tactic to prevent Palestinian statehood in the face of heavy international pressure, he still acknowledges that “the Palestinians, seeking sovereignty, rejected it.” Three decades later, in 2007, a group of Israeli Palestinian intellectuals published a “Haifa Declaration” calling for a one-state solution in which the civil and cultural rights of all sides would be maintained and the Palestinian refugees’ full right of return would be implemented—resulting, in effect, in the transformation of Israel into a Palestinian state. Tellingly, despite the name, Boehm makes no reference to the “Haifa Declaration” in his Haifa Republic.

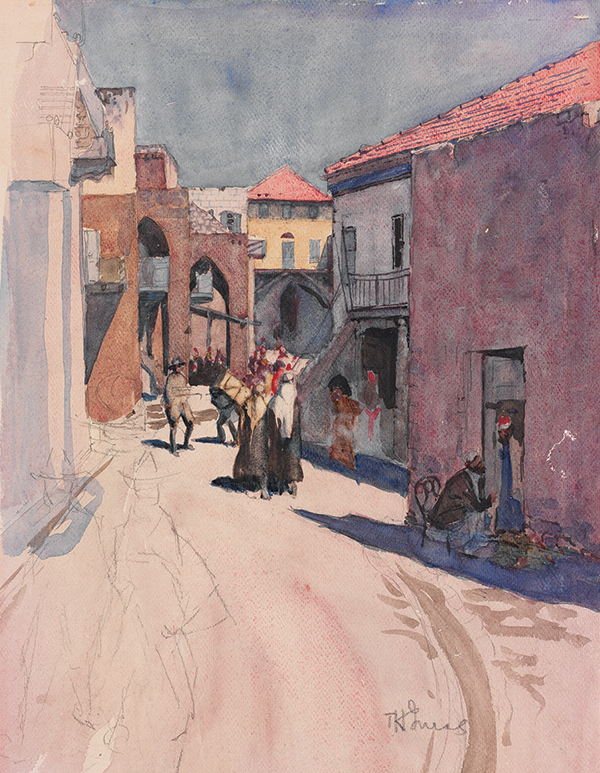

During the mandate era and afterward, Haifa was indeed a hub for economic and civil cooperation. It had a Palestinian mayor in the 1930s and in the 1950s was the home of a Communist party made up of Jews and Arabs. But it was also the site of the Haifa Oil Refinery massacre in December 1947, in which mutual acts of terror resulted in scores of casualties. There were further bitter clashes in May 1948, once the British departed from its port. The city is also the setting for Ghassan Kanafani’s novella Returning to Haifa (1969), to which Boehm only briefly alludes, a book that has become a staple of Palestinian nationalism.

Kanafani tells the story of a Palestinian couple who fled Haifa in 1948, accidently leaving their baby behind. When they return after 1967, they discover that he has been raised by Holocaust survivors and become an IDF soldier. Kanafani, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who was later assassinated by Israel, displays much nuance in his understanding of the Holocaust and Israeli society but ends up claiming that the armed struggle for liberating Haifa and Palestine is inevitable. More recently, during the May 2021 unrest, Arab and Jewish mobs roamed the streets of Haifa, victimizing civilians on both sides. The reality in Haifa is, and always has been, much less tidy and peaceful than Boehm would make it seem.

To achieve the Haifa Republic, Boehm tells us, Israeli Jews must relinquish the idea of Zionism as a state-building project of the Jewish people. This requires an act of “forgetting,” which must, in some sense, include the Holocaust. The Holocaust, he argues, is the main reason why the “Zionist agenda [changed] from a binational one to that of an ethnic nation-state.” And yet, at the same time that he urges the Jews to forget their own recent tragedy, Boehm encourages the Palestinians to engage in an act of national self-remembrance. Building on Yosef Yerushalmi’s claim that the opposite of forgetting is not remembrance, but justice, he says, “We will not just have a better politics, we will also do better justice to the memory of the Holocaust if we allow ourselves, in this sense, to forget.” It seems, nevertheless, that within the context of 1948, Boehm exercises some forgetfulness of his own: the events of Deir Yassin become the rule, not the exception, whereas no similar incidents perpetrated by Palestinians—for instance, the massacre of the Hadassah medical convoy—are mentioned.

This leads us to what I believe is the main shortcoming of the book. For the sake of a theoretical claim regarding morality and politics, which in itself can be contested, Boehm calls for a social, political, and intellectual redesign of Jewish nationalism without regard to the losses it would entail, including the probable losses of life and security on both sides. Boehm’s own binational program addresses these concerns only vaguely:

Each state [in the binational federation] will be responsible for its own internal security. Their security forces will be joined by a mutual defense treaty. A common steering council will regulate the common security interests of both states, as well as the defense of their external borders.

He gives us no reason to believe that this will work. In the end, Boehm’s republic is even more utopian than Herzl’s Old-New Land. He blithely ignores the precarious messiness of binationalism and never tells us how enduring commitments to community, religion, and nationality will be realized by either party in his imaginary Haifa Republic.

Suggested Reading

One State?

Sari Nusseibeh's recent book is a new formulation of an old proposal.

State or Substate?

“Nonstatist” Zionists, as the historian David Myers has dubbed them, have received a lot of attention in recent years. Dmitry Shumsky, a historian at the Hebrew University, is grateful for this scholarship but believes that it has not gone far enough.

State and Counterstate

Debates about Zion and its relation to the diaspora aren't new. David Myers and Noam Pianko have retrieved the forgotten ideas of several interesting figures, foremost among them Simon Rawidowicz. Do they speak to us now?

From the Great War to the Cold War

The facts of Hans Kohn’s life are so extraordinary that it almost seems as if the first half of one remarkable figure’s biography had been spliced together with another’s in the second part.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In