Love, Counter-Historical Style

In Israel, in the aftermath of the Six-Day War, newspapers and magazines were full of pictures of conquering heroes in war-torn uniforms, not of young American Jewish intellectuals poring over books in the library or declaiming to radical crowds outside. You’d have to be an unusual young Israeli to find the latter type of person more to your taste, but that’s just what Rachel Korati had become.

A child of kibbutz Kfar Ruppin in the Beit She’an Valley, she had spent an eye-opening academic year (1967–1968) at Newton High School, an institution “rife with student activism” in a Boston suburb that abounded with Jews. “What really blew open my horizons,” she writes a half-century later, “was the example of the students I met who did not believe their government, neither its claims about ‘liberty and justice for all,’ nor its pronouncements about the war.” She was likewise struck for the first time by the realization of the possibility of “a deeply-held Jewish identity that was neither Israeli nor Israel-centered.”

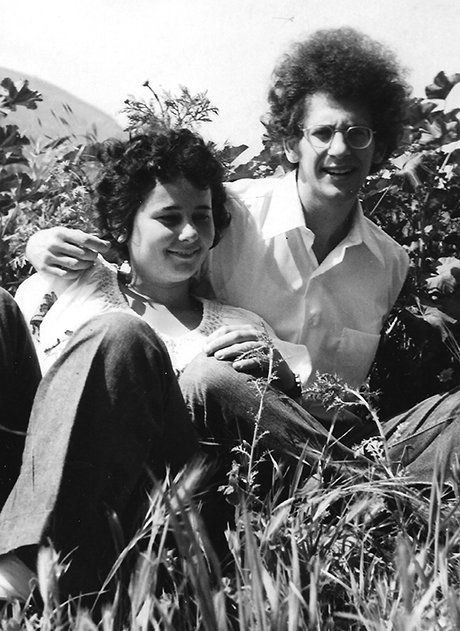

Back home in Israel again, she was now less impressed than most of her peers by the young men “a few years older than me who had fought in the Six-Day War” and “the swagger in the way they walked and the way they talked.” In the summer of 1970, she was introduced to David Biale, a Berkeley undergraduate volunteering on her kibbutz who was, as the woman who brought them together put it, “really into Jewish things.” To Rachel, he seemed the personification of “an American Jewish student, with his lanky torso and gold wire-rim glasses framing inquisitive eyes.” Once he began to talk, she knew he was.

Aerograms Across the Ocean is the story of the largely epistolary and surprisingly reticent (initially, anyhow, and especially for the time) evolution of Rachel and David’s friendship into love and then marriage in the two years that followed their first meeting. They tell it alternatingly, mostly through the quotation of—and commentary on—their half-century-old correspondence on those self-sealing aerogram letters that, before easy international flights, cell phones, and Zoom, were the indispensable currency of international relationships. It’s a very personal tale, and the more intimate side of it is beyond literary criticism, but it also throws a revealing light both on the public life of the period and on the intellectual starting points of the two Biales, both of whom have made important contributions to Jewish life and scholarship. David’s first exposure to Israel took place when his father, a Polish-born lifelong Labor Zionist and a professor at UCLA, spent a sabbatical year there as an agricultural adviser in 1959. This was, David tells us, the best year of his childhood, but it quickly “faded into a distant memory,” so different was it from his life in 1960s California.

Ten years later, on summer vacation from UC Berkeley (to which he had, amazingly enough, transferred from Harvard, to be closer to the heart of the counterculture), he came back to work as a volunteer on a kibbutz in the Negev. Exhilarated by that experience, he became involved with Berkeley’s Radical Jewish Union, a group he later described to Rachel as “so-called New Left people who believe that you can be leftists and also pro-Israel.” He also returned to Israel for a longer visit in April 1970, worked strenuously on his Hebrew, and finally met Racheli—as he would come to call her on kibbutz Kfar Ruppin.

They hit it off easily on a personal level, discussing “Franz Rosenzweig, A.D. Gordon, Martin Buber, the Bible and who knows what else?” What did an 18-year-old kibbutznik know about such things? After her year in America, Racheli had found her old school provincial and stultifying and had transferred to the Jordan Valley Regional High School, which was much more academically rigorous. She was fortunate to have as her instructor in Jewish studies a brilliant young man, Ehud Luz, who would before long become a professor of Jewish thought at Haifa University. Thanks to Luz, she could talk Jewish intellectual history with David as well as listen to the Beatles.

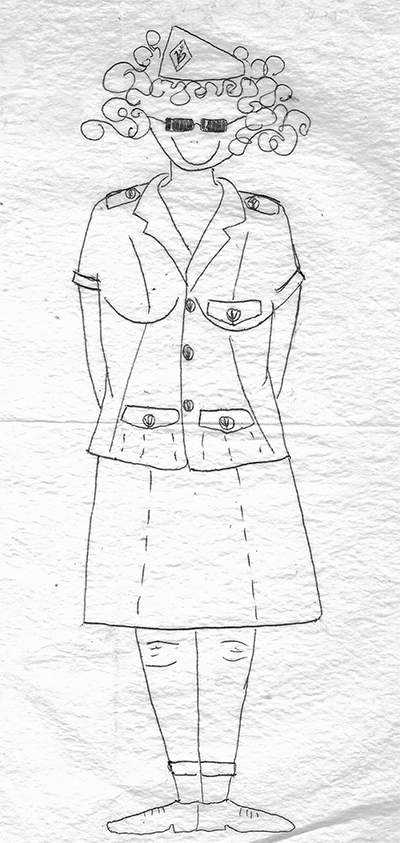

When David returned to Berkeley, their aerograms began flying back and forth, in English and Hebrew, as David continued his studies in the United States and Racheli was drafted in 1971 into the Israeli Army. Among other things, they thrashed out the question of their Jewish identities. Let’s listen to some of it, from its earliest days:

September 10, 1970, Racheli to David:

One of the things I like most about Buber is his anarchism [Martin Buber thought that each person could find an immediate relationship to God without the commandments] It seems to me the only possible approach I could take to Judaism. But I may be wrong—sometimes I think that Franz Rosenzweig’s approach [that one could make a personal commitment to perform some of the commandments] seems impossible for me because I really don’t have a strong enough willpower.

September 19, 1970, David to Racheli:

The Hasidic tale humanizes God and divinizes man by taking the mundane and profane and deriving from it a lesson. . . . I have a lot of other ideas on the role of the Hasidic tale. But instead of writing them here, I will send you a paper I wrote on Elie Wiesel (since you have finally woken to his greatness).

October 2, 1970, Racheli to David:

Suddenly I understood that it’s not necessary to believe in God in order to be Jewish. You have to believe: believe in Am Yisrael [the People of Israel], in belonging to it, to its history. You have to believe that you, as an individual, have a role to play in this world.

October 9, 1970, David to Racheli:

To deny atheism and to accept the burden of history is to commit oneself to one’s people, to become something more than an individual. What I’m saying is that you, Racheli Korati, in spite of your kibbutz education, are really not an atheist.

October 20, Racheli to David:

Objection! Kibbutz life, and thus the aims of kibbutz education, is the opposite of atheism and its implications. You need to believe to be a kibbutznik: believe in ideals, hopes and, more than that, you need to believe in the power of your belief, in your and your haverim’s [comrades’] ability to build a life to fit a higher order of ideals. This is why kibbutz life has a lot, I think, in common with Judaism. They share a basic conception of man’s life and as an accomplishment—a materialization—of the “Kingdom of Heaven on Earth” and a social, human utopia in the kibbutz. . . . What we lack in the kibbutz is a strong, vital connection to Am Yisrael, to our history. . . . And this is what I—we—have to do for ourselves and for the kibbutz and, I believe and hope, for Judaism as well.

October 20, David to Racheli:

We are all trying somehow to be Jewish in Berkeley. Paradoxically, the harder it is to be Jewish, the easier it becomes because you are conscious that anything you do that relates to Jewish history and tradition stands out from the white bread of American culture. I think it is time that people realized how hard it is to be a Jew also in Israel. If you want to do something Jewish that the religious don’t dig, they don’t like you. If you want to do something that implies religion (or tradition), then everybody else doesn’t like you. In some ways, it is easier to innovate in America—people seem to be more open to experimentation.

The most endearing parts of Aerograms relate how David and Racheli, living in such different places, found their way into each other’s arms.

As they did so, their efforts to sort out their Jewish identities continued. Both tested the waters of an observant life—and both stayed on secular dry land. For both, Judaism became above all a thing of study. And for David, who was consumed by his interest in Jewish history, the American university world was a more inviting one than its Israeli counterpart. Zionism, for him, did not necessitate living in Israel; for Racheli—who in retrospect acknowledged that, under David’s influence, she had already begun to assimilate into American Jewish culture while in the Israeli Army—the move to the United States was difficult but not wrenching.

Aliyah, the authors tell us, remained on the table, at least until 1983. Then, while teaching Jewish history as a visiting professor at Haifa University, David received a job offer that he could not accept. They write in the book’s epilogue:

To say that we did not fall in love with the city would be an understatement. And even though David very much enjoyed teaching the Israeli students in Hebrew, he found the atmosphere of the university stifling and contentious.

At the time, we were living in Binghamton, New York, which was also hardly the Promised Land. . . . Fortuitously, a job came open in Berkeley and we were able to complete one circle of our lives by returning to this magical place.

One of the things we learn from Aerograms is how David’s lifelong interest in Gershom Scholem began. “The man is so erudite that it’s disgusting,” he wrote to Racheli in November 1970, after his first reading of Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. “I suppose that there are some who are geniuses enough to be truly original, while the rest of us are almost there but not quite over the magic boundary. The best we can do is to appreciate the true geniuses.” Over the half century that followed, David did as much as anyone to explain and appreciate Scholem. His dissertation, his first book (Gershom Scholem: Kabbalah and Counter-History), and his most recent book (Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah) are each attempts to contextualize and understand this extraordinary figure.

David Biale is, to be sure, an admirer, not a disciple of Scholem, but he has been deeply influenced by him, as, perhaps, has Rachel. In fact, I began to wonder whether Aerograms Across the Ocean can be understood, to some degree, as a kind of “counter-history” to Scholem’s own autobiographical writing.

In From Berlin to Jerusalem, Scholem tells the story of his repudiation, as an adolescent in early-twentieth-century Germany, of the bourgeois assimilationism of his family, his immersion in Jewishness and Zionism, his university education, and his discovery of the Kabbalah. The book concludes with a quietly triumphant account of his settlement in Jerusalem in the 1920s and his appointment to a position at the newly created Hebrew University. Reading David’s contribution to Aerograms, in particular, I was often reminded of From Berlin to Jerusalem. His description of his undergraduate paper comparing Graetz’s views of the Haskalah with those of Scholem reminded me of Scholem’s account of the crucial role that Graetz’s History of the Jews played in his “Jewish awakening.” David’s account of his involvement in Jewish youth movements, both conventional and radical, reminded me of Scholem’s account of his participation in Jung Juda and Blau Weiss. His cameo portraits of contemporaries who were later to achieve some celebrity also reminded me of From Berlin to Jerusalem. But what makes me think of Aerograms as a kind of countervailing response to Scholem is above all its attitude toward the Land of Israel.

Describing the Zionism to which he subscribed as a young man, Scholem emphasizes that it was not so much political as cultural. For him and many others, what was most important “were tendencies that promoted the rediscovery by the Jews of their own selves and their history as well as a possible spiritual, cultural, and above all, social rebirth.” This rebirth or renewal, “whereby the Jews would fully realize their inherent potential,” he and the others believed, “could happen only over there,” in the Land of Israel, “where a Jew would encounter himself, his people, and his roots.” To this, David and Rachel Biale seem to reply, looking back on their happy and productive lives, that it can happen at least as well in America (or at least Berkeley).

Writing in these pages and from the gently reviled city of Binghamton (where I have long held the position that David relinquished), I have more than once expressed my disagreement with David Biale about the viability of secular Jewish self-realization in the diaspora. But that, I hasten to say, has to do with the whole community and the long term. On the individual level and over the course of a generation, wonderful things can be achieved.

David and Rachel Biale have lived rich Jewish lives and published a great deal of important work on a variety of subjects, including the kibbutz, Jewish secularism, women and Jewish law, and Jewish mysticism. It is a pleasure to read how their lives together began in earnest, amorous correspondence.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

History of a Passé Future

At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses.

The Kibbutz and the State

How the position of the kibbutz in Israeli society has changed, and why.

Write a Modern Letter, Live a Modern Life

Imagine that you’re a woman living in a shtetl in 1900: what do you say in a letter to your husband in America if you think he’s cheating on you?

Ilan Chaim

So sad to read of David's passing. We shared a graduate-school apartment in Jerusalem's Ramat Danya, but lost touch after his and Racheli's wedding at Kfar Rupin in 1972. The Egged bus we rented broke down on the way. Were they blessed with children?

Baruch dayan haemet.