The Kibbutz and the State

Just as today’s VIP visitors to Israel are taken to see the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum, so in the first decades of statehood were they ushered off to a kibbutz, especially if they were situated on the left side of the political spectrum. In 1972, for instance, at a time when many New Leftists had come to regard Israel as a present-day Sparta constantly brandishing its sword, the crowned prophet of the student revolution, Herbert Marcuse, visited Israel for the first time. His hosts took him to Kibbutz Hulda, where he was shown around by Amos Oz, who later gratefully quoted him as saying: “Yours is the only socialist experiment that has not spilt blood and so far has not turned bourgeois.”

Overseas visitors lent the kibbutz movement the endorsement it so desperately craved. Nobody else on the Israeli scene seems to have been quite so much in need of constant confirmation from society at large or quite so sensitive to criticism. This vulnerability stemmed from the fact that kibbutz members, even in the 1960s and 1970s, were not content to live a life of pleasant, everyday routine. Since the first decade of the century, they had struggled to bring into existence an altogether new type of society, one that would both establish real equality and imbue ordinary life with special significance. At a time when the descent of the Soviet experiment into the worst sort of tyranny had made the utopian idea appear bankrupt, their achievements continued to hold out the hope that a radical social transformation was within the realm of possibility. But while the kibbutz managed for a long time to present an alternative lifestyle to idealistic young people, it did so with increasing difficulty and growing self-doubt. Indeed, from the day the State of Israel was born in 1948, a sense of crisis was the kibbutz’s constant companion.

A century after the creation of the first kibbutz, more than sixty years since the establishment of the State of Israel, and nearly forty years since Marcuse’s visit to Hulda, the kibbutz movement still has question marks hanging over it. To what extent has its heroic attempt to create a small-scale utopia through education and socialization stood the test of reality? Can one still say of the kibbutz, as Martin Buber once did, that it is an “experiment that didn’t fail”? To address these questions, one must first take a close look at the impact of larger political and social developments on the kibbutz from 1948 to the present.

The War of Independence took a heavy toll on the kibbutz movement: the destruction of settlements, the loss of hundreds of its sons, the hundreds of fresh widows. In the words of Kadish Luz, a member of Kibbutz Deganya Bet and a leader of the Histadrut labor federation, children were “broken up into two categories: those with fathers and those without.” There was, as he put it, a sense of “mission fatigue.” The strain of mobilizing to establish a state, a luminous ideal that had justified so many hardships, had been relieved. A state now existed—and not every day could be as thrilling as November 29, 1947, when the UN had voted in favor of partition. The disappointments that followed were, perhaps, inevitable.

During the period of the British Mandate, the kibbutz had always been the standard-bearer, ready to establish “tower and stockade” footholds in dangerously exposed territory or to volunteer for whatever else needed to be done. After the attainment of independence in 1948, however, the pioneering tasks it had performed in the past were now assumed by the state. Settlement of the land was managed by the government and implemented not by self-sacrificing kibbutz youth groups, but by new immigrants summarily dispatched to frontier regions. Many new kibbutzim were still being set up along the borders, but they were no longer alone. Immigration ceased to be a clandestine operation conducted by kibbutz volunteers and became one of the state’s responsibilities. Instead of volunteering for the underground, there was now conscription into the IDF. Kibbutz members, more than other citizens, volunteered for elite units, flight squads, and the commandos—a price tag of blood held up by members or outside supporters in the face of any criticism flung at the kibbutz. But the army too was, of course, run by the state.

Fully aware of what was happening, David Ben-Gurion, despite his statist orientation, strove to lift the kibbutz movement out of its doldrums: “There is no more harmful or dangerous assumption than that with the establishment of the state, the hour for pioneering has passed,” he declared. “Without a robust pioneering drive to match the needs and possibilities that have increased and intensified with statehood—we will not manage the three great tasks of our generation: ingathering the exiles, making the desert bloom, and security.” But this was reassuring rhetoric: the tasks were on a scale far beyond the means of the kibbutz movement, which could do little but watch as the state usurped its historical role.

The deepest cause for despondency was the fact that despite the massive flow of immigrants into the Jewish state during its first four years, the kibbutz suffered from dwindling numbers: some members left, no new ones came. The Holocaust had destroyed the human reservoirs that might have replenished the kibbutzim. On the whole, the post-Independence immigrants lacked the ideological education dispensed by kibbutz youth goups, whose graduates themselves had only rarely remained on the kibbutz. What is more, most of the newcomers were older and hailed from traditional societies in Muslim countries. They wished to preserve their family framework and had no inclination to adopt a communal lifestyle.

The new immigrants did not understand socialist aspirations; their Zionist consciousness did not embrace such concepts as enlisting for national endeavors, subordinating individual interests to those of the public, or other keystones of a voluntarist and public-spirited worldview. The kibbutz’s culture of direct democracy was alien to most of them, to say nothing of voluntary self-subordination to communal life. They regarded the kibbutz as a bastion of uncompromising secularism hostile to tradition, an institution that dissolved the traditional family, and an ideology that opposed the principle of private property. In addition to everything else, they found it degrading that they were expected to work as manual laborers. It is difficult to imagine how this wave of immigrants could have been integrated into the kibbutz, even if much more energy had been invested in doing so.

Yet Ben-Gurion demanded that the kibbutzim throw open their gates. “What have the pioneers done for three hundred thousand new immigrants?” he railed in the Knesset in January 1950. “During the past two years I have been humiliated and shamed by the pioneering movement’s failure: the greatest thing that has ever happened in its history has taken place, the exodus from Egypt has begun, the ingathering of the exiles has begun, and what have our pioneers done? Have the kibbutzim put themselves to the task?” Ben-Gurion argued that the principle of self-labor (no hired hands) had once been an appropriate barrier against employing Arab workers at a time when it was necessary to get “Hebrew labor” off the ground. But the new realities of the state required that immigrants be absorbed into the productive organs of the kibbutz and given jobs. This, in his eyes, was now the true pioneering. The kibbutz movement, including members of his own party who supported his immigration policy, rejected his demand because it militated against two basic tenets of kibbutz doctrine: equality and communality. “Hired labor in the kibbutz economy,” insisted Shlomo Rozen, the secretary-general of the Kibbutz Artzi Federation, “means the destruction of the kibbutz economy, with its social and its Zionist-class values.” The kibbutz could not have absorbed thousands of hired hands and still remained a kibbutz.

The establishment of the state exposed the duality of socialist and Zionist components that had defined the kibbutz movement from its inception. The kibbutz was to have been the model of the society of the future, a just and egalitarian society even as it shouldered its special responsibilities and missions in the realization of Zionism. But while “national and pioneering tasks were the chief substance of kibbutz life in the period preceding the state’s establishment,” as Haim Gvati, one of the founders of Kibbutz Gvat in the 1920s, put it, they were not always of equal significance. Shlomo Ne’eman, another veteran kibbutznik, distinguished between a “national matter” and “social goals” in terms of the energy people were prepared to invest in each of them: “There is no limit to the efforts people devote to a national matter. Nowhere does one find such dedication to social goals.” In the pre-state period, the Zionist deed was performed by kibbutzim. In fact, Ne’eman claimed, the history of the kibbutz “as a way of life and the kernel of the society of the future” began only after the establishment of the state. Having been displaced from the vanguard of Zionism, and having seen its national functions greatly diminished, the kibbutz had to shift its main focus to the mission of social reconstruction. But there was a problem: what was to fuel the shift? As Ne’eman observed, it is easier to mobilize people for dramatic national tasks than for mundane social ones. A few idealistic youths plunged into the development towns to live with and assist the new immigrants, but they constituted a distinct minority. The vast majority of kibbutz youth was not fired by the idea. Just as Ben-Gurion’s call to embark on pioneering tasks, such as settling the Negev, evoked little response, so too did the attempt to have the kibbutz negotiate a 180-degree turn to focus on being a model of a utopian, egalitarian society. The prospect did not stir the imagination or generate enthusiasm. As if to convince themselves that they had not lost the luster earned by carrying the Jewish people on their shoulders, movement leaders kept enumerating the kibbutz’s accomplishments: settling on the country’s borders; making the desert bloom; developing modern, viable, and advanced agriculture; and the volunteer service of their young people in elite IDF units. The anxiety that the kibbutz movement was losing its central place in Israeli society gnawed away at her devoted members and supporters in the 1950s and 1960s.

The centrality of the kibbutz in the pre-state period and the subsequent decline in its status were reflected in Hebrew culture. When Hannah Senesh composed her poem “My God, May it Never End” not long before she parachuted to her death in 1944 in a doomed rescue mission behind Nazi lines in Hungary, she was evoking memories of the Mediterranean coast near Kibbutz Sdot Yam, where she lived. S. Yizhar’s first story, “Ephraim Returns to the Alfalfa,” is set on a kibbutz. The first novels of the most important post-Independence writers are also set on kibbutzim. Naomi Shemer, who famously wrote the lyrics for “Jerusalem of Gold” in 1967, had, in her early years, sung of the eucalyptus grove at Kibbutz Kinneret, her birthplace. Moshe Dayan’s eulogy for Ro’i Rothberg, a victim of terrorism at Kibbutz Nachal Oz on the edge of the Gaza Strip, symbolized the central place of farmer-soldier units and frontier kibbutzim in the public consciousness of the 1950s.

But this was not to last. Since the 1960s, city life has replaced the kibbutz as the main scene of action in Hebrew literature. When the kibbutz features in a work such as Yehoshua Knaz’s novel Infiltration (1986), it is meant to represent the domination—unto death—of the individual by society. This had been an important theme of kibbutz literature since David Maletz’s pioneering novel, Circles, which appeared in the early 1940s, but by the 1980s, it dominated the scene. The kibbutz became the symbol of the misery that Zionism inflicted on those who had followed it to the utopian wilderness. Thus, for example, the institution of children’s dormitories became a topic of incessant discussion in Israeli culture, as if an unhappy childhood were the sole preserve of kibbutz society. It is difficult to find novels in which the kibbutz plays a major role in the past few decades. Asaf Inbari’s recent book, Homeward, about the history of Kibbutz Afikim, where he was born in 1968, reads like a requiem.

In this bygone world, people had often asked whether the kibbutz ought to serve as an avant-garde, charged with guiding Israeli society towards social revolution, or as a prototype for that society. In both cases, the relationship between the kibbutz and its surroundings vitally informed every vision: whether the kibbutz advanced revolution or set an example, there was a symbiosis between the kibbutz and the larger society. But by the late 1950s, Kadish Luz, by then Minister of Agriculture and a symbol of integrity and modesty, could protest that “our main difficulty today is that the very way of life and the need for it in the eyes of the broad public outside the kibbutz is problematic, and this attitude has filtered down to kibbutz members themselves.” New definitions of the state’s needs, tasks, and aims replaced the tasks traditionally undertaken by the kibbutz. Careers in science, the military, or service in the top tiers of the state apparatus were now considered no less important than being a kibbutz member. The kibbutz still enjoyed symbolic prestige; it was still a destination of foreign VIPs. But the milieu was changing. Minister of Education and kibbutz member Aharon Yadlin observed that the kibbutz had lost its supremacy in Israeli public consciousness and that people now saw “the kibbutz member as strange and eccentric, and his creation [the kibbutz] as anachronistic.”

The kibbutz was never meant to be a sect. Its connection to the broader Zionist movement was vital to its self-image. But how could it avoid being marginalized when Israeli society as a whole relinquished the pioneering ideals of the early days and came to resemble the western bourgeois world? The process was stealthy: slowly, almost imperceptibly, Israeli society changed colors. The evaporation of social idealism in the general society caused the kibbutz to regard itself, in the best case, as an oasis and, in the worst, as an anachronism. In this atmosphere, the kibbutz was destined to shrink: there would always be drop-outs, but it was doubtful that there would be newcomers.

After the War of Independence, kibbutz members had sought to improve their standard of living, not with luxuries (heaven forbid) but with simple commodities: reasonable living quarters with indoor bathrooms so as to dispense with communal showers and sprinting to WCs in the rain; some furniture for the private living quarters; and more freedom in spending the personal funds allotted to them. As families grew larger, members sought housing that would enable them to host their dormitory-dwelling children in the afternoon. The demands were modest, not exceeding the accommodations of a worker’s family in town. This particular comparative measure was critical both existentially and ideologically. Too large a gap would have caused people to leave the kibbutz and move to town. And the kibbutz had always contended that communal life was not only more just and equitable, but also more efficient economically. In 1949, Joseph Sprinzak, a veteran labor-Zionist politician and the first speaker of the Knesset, but himself a city-dweller, sought to define sympathetically the outlook of the kibbutz’s new standard-bearers: they are “capable of supreme self-sacrifice at any moment but not prepared for the ascetic self-denial of monks or hermits.”

“Is it inevitable that the accumulation of property will lower the temperature of the vision?” demanded a kibbutz member. “Can only people without means and without professions create a communal society?” That is, can a commune be sustained only at a low standard of living? And is it destined to pass from the world with the onset of economic prosperity? Sixty years later, this question sounds prophetic.

The rise in living standards was accompanied by a shift in the balance between the individual and the kibbutz. More and more, members sought some privacy within the communal framework. Electric kettles showed up first in family apartments, then record players, radios, and refrigerators. The kibbutz’s common domain also grew steadily weaker: with the advent of television, participation in kibbutz assemblies fell. The children’s dormitories fought a losing battle. As a result, family members gathered together to eat in private homes instead of in the communal dining room. The home became a focus of identity. The bond to the kibbutz was no longer preserved by ideology, which had collapsed, but by inertia and a sense of belonging to place and family.

The kibbutz had to respond to its members’ intellectual ambitions and cultural aspirations as well. Young people’s paths to the university could no longer be blocked and they had to be allowed to study whatever they wanted. The slogan of “self-realization” (through living on the kibbutz) was replaced by “personal growth.” Individualism eroded group commitment. Old-timers felt the kibbutz slipping away from them. “We are witness to a shift in emphasis,” complained one veteran in 1970, “from kibbutz to economy, from vision to interests, from all-embracing moral standards to criteria of efficiency.” Members of the kibbutz’s third generation did not accept their parents’ doctrines, and demanded the freedom to shape their own lives. “We see nothing wrong with the development of kibbutz careerism,” a younger member declared. So as not to lag behind the rest of the country, the kibbutz industrialized. This facilitated a higher standard of living and, just as importantly, provided an entire stratum of young people with challenging, interesting work in industrial plants where instead of picking oranges they could design and develop new plastic products or precision metal parts. Agriculture lost its primacy as the main branch of the kibbutz movement. A whole way of rural community life, bound up with the celebration of nature holidays and the education of youth towards manual labor, lost its bearings.

In November and December of 1971, the journalist Ya’ir Kotler published a series of articles entitled “The Kibbutz in the Era of Affluence” in Ha’aretz. He portrayed the kibbutz as wealthy, not truly egalitarian, petty bourgeois, disappointing to young and old, frustrating to those working for the members’ general good, imprisoned in the rhetoric of the past, and devoid of new horizons. The letters-to-the-editor columns of Ha’aretz and other newspapers were soon full of complaints and protestations: “Let’s see if you come close to living by the criteria you demand of the kibbutz.” “Look how much we give to the state, and the esteem in which the world holds us.” But there were also more balanced responses. One kibbutz member wrote that, contrary to what some people may think, “the kibbutz is not a ‘nature reserve’, but an integral part of Israeli society” despite all of its problems. “Three and a half percent of the population cannot long withstand the general current of society.” No less than Kotler’s original articles, this statement pointed to an inherent paradox: to the extent that the kibbutz strove to reflect innovative trends in the economy and society, and sought to satisfy the third generation’s more individualistic ambitions, it moved away from its idealistic-pioneering image and lost its standing in Israeli society. The pioneering-national message melted away with the attainment of statehood.

The growth and consolidation of the kibbutz movement took place in the 1920s when the Jewish community in Palestine was pervaded by an almost messianic pathos, by hopes of revamping the world here and now. These hopes were connected with events in Russia—the country of origin of many kibbutz members and the guiding light of socialist

actualization to which all lifted their eyes. This was of course an illusion, ending in one of the greatest disappointments in human history. But as long as the USSR sun still seemed to shine, the kibbutz in Palestine had a model against which to measure itself.

Even those who were repelled by Soviet brutality were, to some extent, reassured by the very existence of that huge state where a large-scale experiment was under way to put socialism into practice. They were fascinated by what they saw as a movement from exploitation to justice, a bold endeavor to refashion man and society. Different parts of the kibbutz movement lost their “Red fascination” at different times. The last ones sobered up after the USSR’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, but in the following decades, too, the USSR continued to serve as a yardstick for comparison. By the end of the 1980s, however, it was finally clear to everyone that the Russian experiment had failed in human, social, and political terms.

Even earlier, however, toward the end of 1960s, some young kibbutzniks had begun to look in an entirely different direction for inspiration. Members of the second and third generations of kibbutzniks began to explore traditional Jewish sources. At the center of this phenomenon was the journal Shdemot, which served as a platform for young people disillusioned with socialism, fed up with the spiritual emptiness of the kibbutz’s affluent society, and searching for God. Yearning for spiritual content and elevation, these people called for traditional holiday celebrations instead of the new rituals invented by earlier generations of kibbutzniks. They and others like them spurned the kibbutz Haggadah, which reflected contemporary culture and sometimes current events, in favor of a Haggadah to which God had been restored and which became increasingly similar to the traditional one. All of the wonderful quasi-biblical ceremonies devised by creative artists and teachers in the heyday of the kibbutz to express the new experience of a village culture were now judged in terms of their fidelity to Jewish tradition. The ushering in of the Sabbath, including candle lighting, gathered momentum. The long-neglected holiday of Yom Kippur came back into the picture. The socialist bookshelf made way for the Jewish one. Kibbutz members took to studying Judaism at yeshivas or universities. All of this was a reaction to the exile of the Divine Presence from the kibbutz, as the poet Abba Kovner put it, an attempt to compensate for the death of the socialist utopia.

This new approach to Judaism was a component of kibbutz culture that radiated outwardly to secular Israeli society. It awakened an interest in Judaism among many young people seeking an escape from the cold, modern world. Ironically enough, however, within the kibbutz itself it was a different story. Most people were not interested in such things. The intelligentsia, the spiritual elite who had established the Efal Seminar, Oranim College, and the Kibbutzim College of Education, and who had studied “impractical” subjects such as history and Jewish philosophy, felt uneasy and frustrated with the ideological atrophy of the kibbutz. The economic managers, the active group that ran the industries supporting the kibbutz, were hardly thrilled by the steady growth of expenditure on education and higher studies not geared to kibbutz needs. Very likely, they felt that they were financing “idlers.” Most kibbutz members sat on the sidelines, preferring to stay home and watch television rather than participate in discussions on the meaning of life on the kibbutz.

The kibbutz’s status as a leading actor in Israeli society continued to decline through the early 1980s. It still played an important part in settlement and the IDF, and it still exhibited impressive economic viability. But gone were the days when kibbutz members featured prominently in the Knesset or the government. They did no find their place in the leadership of the Labor movement, much less act as catalysts in Israeli politics. The earthshaking victory of the Right in 1977 had turned their world upside down. But apart from bestirring themselves to campaign for the Labor Party in the following elections, they did not shake off their lethargy. It was as if the flame that had once burned in the hearts of their fathers had completely died out with the changing of the generational guard.

The kibbutz’s supposed “Garden of Eden” had for some years harbored a snake: the metal-working, woodworking, electronics, and plastics industries established in the 1970s had revitalized the kibbutzim economically, but they rested on hired labor. The workers hailed from development towns, the managers from kibbutzim. This meant that there were now two opposing classes: employers, who devoutly upheld equality at home, but whose factories did not promote workers to management positions; and the children of those same Eastern Jews, who had been uninterested in joining the kibbutzim and grew up in development towns, like Kiryat Shmona, Yerucham, and Beit Shemesh, on the bitterness, insult, and pain of societal rejection. The egalitarian standard-bearers found themselves at the center of a class and ethnic confrontation.

Several months after the 1981 elections, Israeli television broadcast a program including a segment in which a member of Kibbutz Manara on the Lebanon border was seen swimming to his heart’s content in the kibbutz pool. Menachem Begin, in an interview on Israel Radio on the eve of Rosh ha-Shanah, referred to this by then notorious kibbutznik and the pool as an arrogant expression of a culture of excess: “That man on a kibbutz, lounging in the pool as if [you were watching] … some American millionaire and talking with a good deal of condescension? Did I sit at that swimming pool? I have no such luxury.” Begin’s crude and demagogic use of the “ethnic card” reflected his awareness that the kibbutz, for all its faults and weaknesses, still posed an alternative to his new regime. Moreover, it still symbolized an idealistic society, the best of the Israeli nation. If Begin wished to rewrite the history of Israel and give voice to groups like his own Irgun, which had been excluded from the Zionist narrative, he had to undermine the symbolic keystone of the Labor movement—the kibbutz—by depicting its members as people living off the fat of the land while they exploited hired workers and denied these workers’ children admission into kibbutz schools.

The Prime Minister’s words created a media storm. The kibbutzim had some passionate defenders. “You obliterate the kibbutzim, you obliterate Israeli identity,” wrote the journalist and novelist Amos Keinan. “The kibbutz does not belong only to the kibbutz, only to the Labor movement, but is an asset to all Israel, to the Jewish people as a whole, and one of the wonderful expressions of Jewish genius.” Other leading journalists and writers rushed to the kibbutz’s rescue and Begin was quick to apologize, though he termed the torrent of retorts condemning him “hysteria.” Nonetheless, the damage had been done. In vain did kibbutz economists pull out numbers to show that they did not enjoy economic privileges. In vain did they list all the things kibbutz members had done on behalf of development towns. In vain did they explain that it was every kibbutz, not every kibbutz member, that had a swimming pool. The image of the rich, patronizing Ashkenazi kibbutznik was fixed in Israel’s internal discourse on Eastern Jews.

Kibbutz members were deeply pained by this campaign of delegitimization. Where had they erred, they asked themselves. Could things have been done differently? If so, how? Martin Buber’s famous definition of the kibbutz as an experiment that had not failed was repeated again and again, as if it were a magical formula with restorative powers. Certainly, the kibbutz did not quite fail—as a way of life it continued to be a symbol and an example to emulate. But neither did the excitement of the pre-state period return, except perhaps in wartime or on kibbutzim facing security dangers. In normal times and on calm kibbutzim, it was life in town that appeared interesting, innovative, and challenging.

Ironically enough, it was the economic collapse of considerable parts of the kibbutz movement in the late 1980s that disrupted this drab state of affairs. Affluence proved to have been temporary, perhaps even illusory. Yet a return to austerity and “making do with little” was not an option in late 20th-century Israel. The principles of egalitarianism and communalism were sacrificed on the altar of economic efficiency. The collapse of the USSR resonated powerfully: economics had defeated ideology, and the expert in social organization replaced the charismatic leader. The aspiration to reshape the world was replaced by a far more modest concern: to ensure a dignified old age, at least, for the generation that had given its all for the kibbutz.

Was the collapse of the kibbutz the result of poor management or did it point to the system’s essential failings? Socialist ideologue Yitzhak Ben-Aharon believed to the end of his century-long life that in Israel, as in the USSR, the failure had not been inevitable, but rather the result of the incorrect application of correct principles. Since a large part of the kibbutz movement still believes in communal life and egalitarianism, and even succeeds economically, this assumption cannot be dismissed out of hand. At the same time, the inherent contradictions of raising a managerial class on the kibbutz were not merely accidental. The kibbutz spurned the idea of a socialism of poverty, holding up its economic success as proof of the success of its way of life and in order to ensure the loyalty of its next generation. But to society at large, the elevation of its standard of living made it seem that the kibbutz was shedding its pioneering spirit and, internally, it made the intellectual discourse sterile and created a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle. The result was an impoverished socialism. If Marcuse was right in 1972 that the kibbutz had “so far not turned bourgeois,” he was not right for long.

All of this raises the question of the character of the third kibbutz generation. Its spokesmen have claimed that they are not prepared to accept the truths and norms of their parents, that they are entitled to choose their own way of life just as their parents once did. Does this attest to the success of kibbutz education or its failure? A great deal of creative thinking, as well as financial and intellectual investment, went into educating kibbutz children. Ultimately, communal education produced kibbutz members who take naturally to physical labor, excel at team-work, and are prepared to work hard. But it did not create a “new man” in the socialist sense, free of possessiveness, jealousy, and personal ambition. Education and ideology proved powerless against the influence of the surrounding society and, perhaps, against human nature, which turned out to be resistant to all attempts to redesign it. If the utopian project failed in the coercive world of the USSR, it could hardly succeed in the open, democratic society of Israel.

In the end, the fate of the kibbutz reminds us that idealistic projects are always shaped by the great events and movements of history. There are indeed moments when it seems as if the human will can change the course of history. But it is important to remember that Zionism was realized not only through the will of its champions and their sacrifices, but as the result of historical processes beyond its control: two world wars, colonialism and decolonization, the Bolshevik Revolution, the Holocaust, the Cold War, and other defining world events without which it is doubtful that any demonstration of Zionist “will” or kibbutz idealism would ever have prevailed. It was realized in an era in which states fought for their very existence and nations stood on the brink of the abyss. In this turbulent era, there was room for worldviews that regarded the community and the nation as the bases of human existence, and private life, comforts, and personal growth as secondary to the needs of the group. However, individual and general interests intersected only in times of massive emergency. In the absence of any such emergency over the past sixty years, new winds have blown away old ideas and fashions. If the Zionist idea had been born today, it would not have caught on. Herzl’s “If you will it, it is no legend” has symbolically evolved into current Tel Aviv graffiti featuring a picture of the founding father and the words: “No will, no way.”

The same is true of the kibbutz. To be sure, the economic collapse of the 1980s could have been avoided. But it was impossible to prevent the decline in the kibbutz’s stature, both in the state and in the eyes of the kibbutznik. The disappearance of national-pioneering tasks had slowly dissolved any sense of urgency; constant attrition and the inability to attract new members had undermined self-confidence; and processes beyond the kibbutz movement’s control had produced enormous changes in the public and social climate.

But the story of the kibbutz has not necessarily reached its end. Although the movement has declined over the past sixty years, it has by no means disappeared. Nor has it intellectual legacy been forgotten or rendered obsolete. One can readily imagine that Israel might, in the future, face the sort of emergency that could revivify the kibbutz movement, or perhaps stimulate the creation of something new and different that will nevertheless draw upon its heritage.

Suggested Reading

The Zionavar Tapestry

Canadian fantasy writer Guy Gavriel Kay weaves unique novels with Jewish themes but never quite escapes Tolkien's orbit.

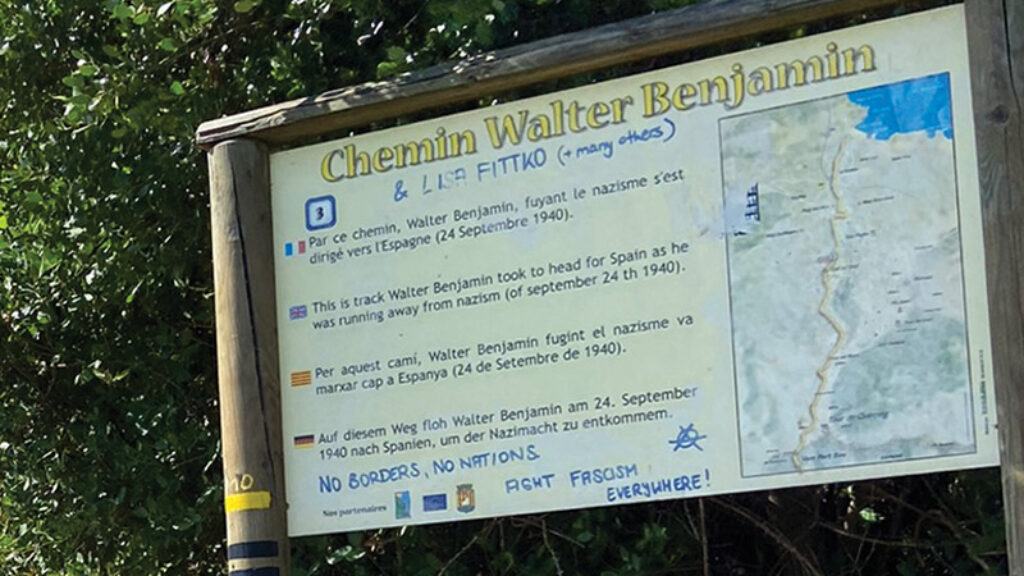

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

If This Is a Man

Primo Levi often claimed that he was first and foremost a chemist and not a professional writer, but anyone who reads him with care will be moved by the sober lucidity, subtlety, concision, and analytical power of his prose.

Black Hats, Green Fatigues

They don't like the Z-word, but new haredi IDF soldiers sound a lot like the old Zionists.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In