History of a Passé Future

In 1945, Martin Buber famously called it the one utopian experiment that had not failed. And for decades, the kibbutz took pride of place among Israel’s most innovative accomplishments. But with a post-1967 capitalist juggernaut bulldozing the old socialist experiments, the kibbutz ideal has undergone, by now, five decades of disillusion and disintegration, followed by a refashioning to save community at the expense of its original (and naïve) idealism. Most kibbutzim have either partially or fully privatized, once bustling dining rooms are now largely empty, and agricultural labor is more likely to be performed by Thai migrant laborers than by the “New Hebrew Man” envisioned by their founders.

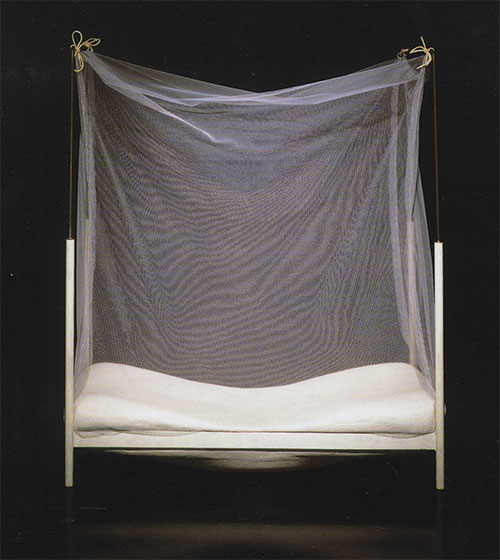

Kibbutz education spearheaded these changes. At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses. In a small avalanche of art and writing, both memoir and fiction, graduates of the utopian educational system opened up a public reckoning with an upbringing they often depicted as traumatic. Yael Neeman’s We Were the Future is one of the very few of these testimonies to appear in English. As such, it offers a window into a vigorous debate taking place in Israel over an important chapter in Zionist history. Indeed, in 2005, more than 300,000 Israelis flocked to a Tel Aviv Museum exhibit on kibbutz education. The most powerful piece for many viewers was by Efrat Natan: a pure-white, empty bassinet suspended in a black void. It left the message open to the viewer’s interpretation: horrifying or serene?

Neeman’s book chronicles, in meandering, yet at times beautifully evocative prose, her life from kibbutz childhood to young adulthood. After her army service and another year of work on the kibbutz, she left, disillusioned with the collective’s promise and disappointed in herself. Toward the end of the book, Neeman writes:

The beauty of our kibbutz was incredible. We could never get used to it. We all felt unworthy of it and the system. Who could say no to an attempt to create a better, egalitarian, just world? We didn’t say no. We defected.

It is a melancholy trajectory she describes, from a childhood “dipped in gold” to the realization that “we were born to a star whose light had long since died.” To say children are the future may be banal, but putting it in the past tense, as Neeman’s title does, aptly expresses the pathos of the demise of an idealistic dream. Neeman articulates the radical transformation kibbutz founders sought through the eyes of children such as herself: “Their intention was . . . to separate the children from the oppressive weight of their parents . . . to protect the children from the bourgeois nature of the family.” “The Internationale” was sung at every kibbutz holiday: “We will destroy the old world, down to its foundations . . . then establish our world [with] nothing yesterday, everything tomorrow.” We Were the Future presents a dual picture of idealism and disappointment. Neeman and her peers experienced both exhilarating freedom and abandonment in what she calls a social “experiment of enormous proportions.”

As a product of this collective education myself, I found much of Neeman’s account of childhood on the kibbutz vivid and authentic. There were the occasionally dangerous shenanigans when we were unsupervised, especially between our bedtime and the arrival of the kibbutz member on overnight duty. Neeman’s group made a bonfire in their dining room. Mine tried something similar—with flint stones, like the cavemen we’d learned about—but (fortunately) we failed. There were the mandatory afternoon naps when you had to lie still in bed, without even being allowed to go to the bathroom. In the middle of the night frightened children would sometimes run to their parents’ homes, often to be forcibly returned.

As Neeman describes, we lived with a strange mix of anxiety and security: We dreaded infiltrators entering the kibbutz and the howling jackals, but, at the same time, we were unafraid to be left alone at night, taking care of ourselves. Our courage stemmed from an abiding sense of solidarity. In my room in kindergarten, we had a boy who still wet his bed. We would wake up before dawn and change his sheets and pajamas, stuffing the wet ones deep in the middle of the laundry basket, so the metapelet (caretaker) wouldn’t find them in the morning and he would be spared humiliation. We were only four years old but already understood it was up to us to take care of everyone in our group and make things right on our own.

Adopting the narrative voice of young children, almost always using “we,” rather than “I,” allows Neeman to capture this collective identity. “We were so close to each other, all day and all night,” she writes. “Yet we knew nothing about ourselves.” This is deeply sad and it rings true of at least some kibbutz children. The lack of self-knowledge among kibbutz children was already noted by Bruno Bettelheim in his controversial, yet influential, critique of the kibbutz upbringing, The Children of the Dream (1969). Nevertheless, it must be noted that those who grew up in the children’s houses have, as a rule, turned out no different than the norm in Israeli society.

Neeman’s decision to write from a child’s perspective in the first-person plural also has significant drawbacks. One often wonders whether she is truly capturing the collective consciousness of her children’s house in the 1960s or reading later attitudes into it. For instance, in describing what she and her peers knew of the siege of her kibbutz, Yehiam, during the 1948 War of Independence, Neeman writes, “was it an attack on Yehiam, or in the Auschwitz camps? One convoy merged with another; an armored vehicle with a train.” But in kibbutz education, stories of the 1948 war were deliberately marshaled as tales of heroism and victory in diametric opposition to the narrative of the Holocaust, so this conflation seems unlikely.

It is possible that Neeman’s conflation of war in Israel and war in Europe can be attributed to her youth, but her naiveté isn’t simply limited to early childhood. She doesn’t mention the Yom Kippur War at all, which took place when she was 13, took the life of one of Yehiam’s young men, and was an unprecedented national trauma. Later, stationed in a Jordan Valley IDF base, she meets a fellow soldier awaiting trial for refusing to serve in the occupied territories and writes “only then did I realize that the battalion was in the occupied territories.” This is simply not credible. Her kibbutz was in the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair movement where political education and activism were both vigorous and mandatory. No one with such an education would have been this oblivious.

Neeman’s choice of the first-person plural becomes odd, and, I would argue, both distorting and confusing. The “we” switches meaning from “I,” to “I and my siblings” when she discusses her own family, to “I and the other kibbutz children.” She recalls a rare occasion of sleeping in her parents’ home: “[We] slept in our parents’ house, a strange and terrifying sleep. Our parents’ close proximity seemed sick and crazy, as if we were locked in an embrace with death, which sang us a lullaby.” For me and all the other kibbutz kids I’ve ever known, the rare “sleepovers” at our parents’ were a treat; our “we” cannot be included in Neeman’s “we.”

I have little doubt that Neeman’s family was atypical, in fact, likely disturbed. She writes of her parents:

[T]hey didn’t always take the things we brought from the children’s house and hang them up or collect them. In fact, they never did. When we brought a carving we made from avocado pit, our parents would throw it in the garbage pail without the slightest hesitation.

Neeman records no reaction from her parents to her emotional difficulties in adolescence and young adulthood, including a long unspecified illness, dropping out of school, and discharge from the army on psychiatric grounds. None of this, of course, impugns the interest or power of the story she has to tell, but it does suggest that her experience was not representative of her peer group. In reality, as in every society, there were many family constellations and dynamics in the kibbutz. Kibbutz children too, though undoubtedly deeply informed by the experience of collective education, ended up as adults who reflected their nuclear family more than the communal environment.

It would be unfortunate if the English reader’s sole exposure to recent books about the kibbutz were limited to We Were the Future. Assaf Inbari’s Ha-baita (Going Home, 2009), which has not been translated yet, portrays the founding generation of his kibbutz, Afikim (south of the Kinneret), with both loving compassion and ironic distance. He enters into the founders’ minds, their conversations, their almost religious devotion to work, their ardor for the land and the place they lovingly call by the Russian diminutive “Totchka” (the spot). He also perceptively dissects their inability to comprehend and integrate the radical changes in the kibbutz taking place before their eyes, telling a story at once inspiring and heartbreaking.

Amos Oz’s Bein chaverim was translated as Between Friends in 2014, although the English title cannot render the layered meaning of “chaverim” in the kibbutz: friends, comrades—with all the old socialist connotations—and fellow kibbutz members. Oz’s linked short stories are psychologically complex and astute, the very qualities missing in Neeman’s book. All of the kibbutz members, including the powerful movers and shakers, are lonely, wounded, and emotionally stifled. But there are also fleeting moments of grace and kindness.

As it happens, Oz and Neeman shared a translator for their kibbutz books, Sondra Silverston. Generally speaking, Silverston provides us a good translation but it is marred by occasional odd choices and infelicities. For instance, she misses what is going on in Neeman’s description of how children were befuddled by a sign posted in every kibbutz car. It warned against throwing cigarette butts and matches out of the window. Like Neeman, we misread “bidlei” (butts) as “ba-dli” (in the pail). Silverston never explains the misreading, leaving us puzzled about this mysterious “pail.”

The 19th-century historian Moritz Steinschneider famously—and utterly erroneously—said that the task of his school of scholarship was “to give Judaism a decent burial.” Neeman perhaps has set out to undertake a similar task, but the patient, the utopian kibbutz, died long ago and the time now is not for eulogies, but for and a more accurate historical assessment.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Chopped Herring and the Making of the American Kosher Certification System

In 1986, the discovery of non-kosher vinegar in a classic Jewish delicacy led to a revolution in kosher supervision.

This Shall Not Be in Vain

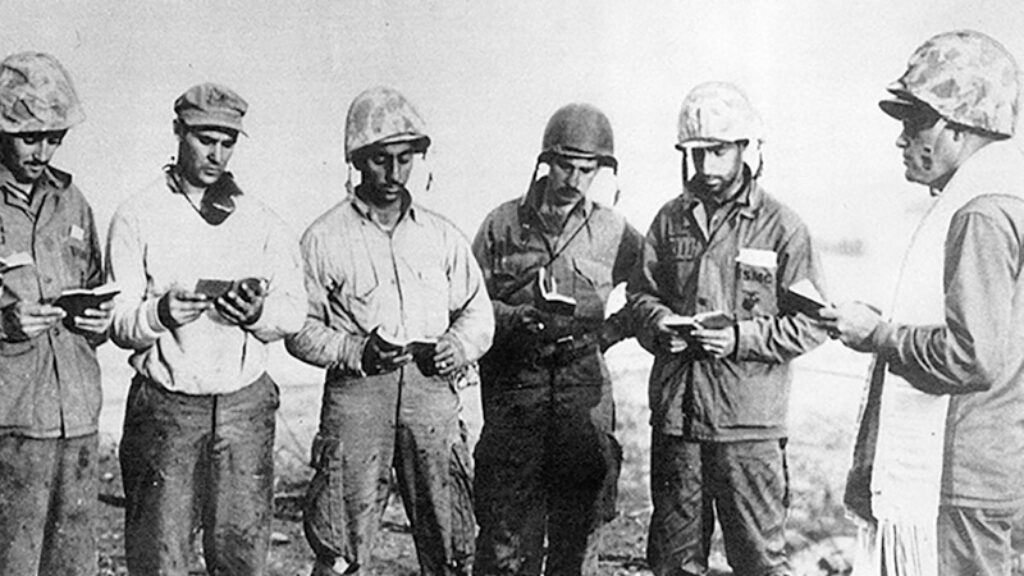

Rabbi Roland B. Gitelsohn was a pacifist when World War II started. Four years later he was chaplain at the Battle of Iwo Jima. His long-lost memoir has just been published.

Reprise of the Repressed

So much of American Jewish pop-culture sets out to shame the audience, one wonders why there's such an appetite for it.

What They Talk About When They Talk About Golems

On golems and global conspiracy theories.

gailtaback

Rachel Biale's review of Yael Neeman's book, "We Were the Future..." really helps those of us who never lived on a kibbutz nor grew up in the children's house of a kibbutz, a balanced view of the experience. The review is not only well-written, but it is more meaningful coming from Rachel Biale as she, herself, was a child educated and raised in a kibbutz, not unlike Yael Neeman's. She conveys the author's "melancholy trajectory" for a dream that no longer can be. Biale shows sympathy and an understanding of the idealism of the early kibbutz movement and she also acknowledges the author's feelings of abandonment as well as of security of community. Since the social experiment of the kibbutz utopean dream has undergone so many changes and for all purposes no longer exists as it did in Israel's earliest years, it is especially interesting to read a first-hand account of the experience of those who grew up in this life. I look forward to reading Neeman's book.