An Inch Deep and a Mile Wide, or Vice Versa

It’s been twenty-five years since Larry David first strutted and fretted his way in front of the camera, appearing on Curb Your Enthusiasm, an HBO show whose title seemed to announce a particular kind of lowering of expectations, which bordered on, well, self-hatred. When Curb first aired in 1999, David was familiar to comedy connoisseurs as co-creator and co–head writer of Seinfeld—and the guy who failed to stick the landing of the iconic series. (David had returned to Seinfeld after a several-year hiatus to write a hugely controversial outro that threw the show’s famous quartet of Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer in jail for what amounted to serial misanthropy)

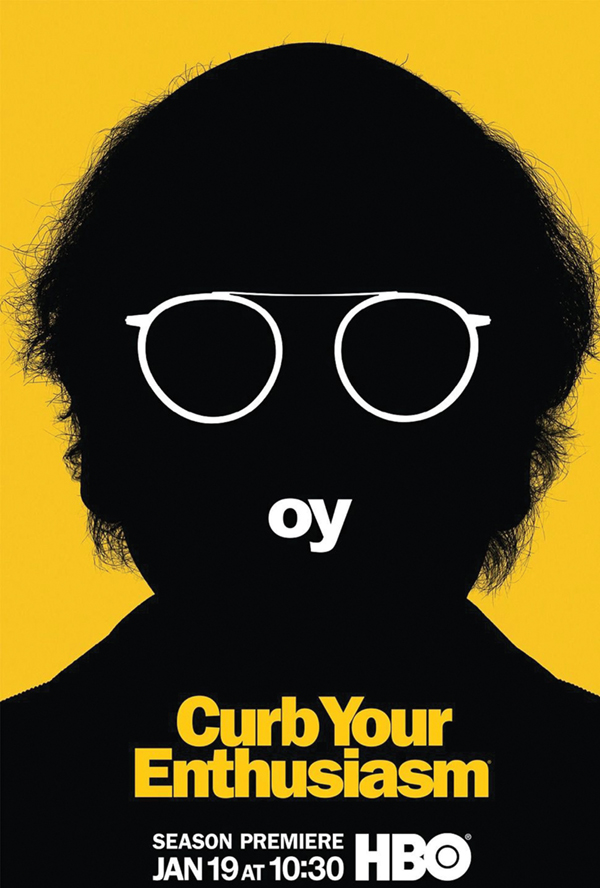

A generation has now been born and grown to young adulthood who know and even love Larry David for his solo work, the stuff he did after the band broke up. Curb and David are household names (the latter’s woolly fringe of hair, framing a magnificent bald head and round glasses, became so recognizable that HBO took to advertising the show with his cranial silhouette alone). Last year, when Curb’s twelfth season launched, David announced that the show had finally reached its natural end (after all, he might have noted, it had reached 120 episodes). And so it seems like a good time to pose the question: Was it good for the Jews? Or given how good the show often was, what sort of good was it for the Jews (and Jewish comedy)?

Curb and Seinfeld have a lot in common, unsurprisingly, most notably in how its characters navigate mundane situations in the pettiest of ways. Still, the circumstances are different, and that matters. Seinfeld was populated by youngish and Jew-ish characters. (Yes, technically only Jerry was Jewish, but Kramer, Elaine, and George were Jews “in the witness protection program,” as Jerry Stiller, who played George’s father, once put it). And although “making it,” to use the famous Podhoretzian formulation, wasn’t centralto Seinfeld, it undergirded its characters’ and creators’ efforts to have Jews succeed—in life and on television.

In 1989, when NBC greenlighted Seinfeld after the pilot, it ordered only four more episodes. It was one of the lowest episode orders in the history of network television—and the worry was not that it was “a show about nothing”; it was that it was really a show about Jews. And so Jewishness peeked out in moments like an episode in which Jerry makes jokes about his dentist and Kramer accuses him of being “an antidentite.” But Seinfeld didn’t turn out to be too Jewish. It made it.

Curb, by contrast, is about people who have already made it. Larry and company, in ethos if not in actuality, are retirees, flush with wealth and success in Hollywood, a society that genuflects at both. It takes a lot to fritter the wages of that success away. But Larry almost manages. And he does so in ways that are saturated with Jewish language, situations, and content that Seinfeld could never dream of, given the nature of network television during its run.

Curb was launched relatively early in the epoch of cable television, when “It’s Not TV, It’s HBO” was still a fresh slogan. One of the ways Curb wasn’t TV was its portrayal of distinctively and outrageously Jewish moments. David treats ex-wife Cheryl’s family accidentally—but come on—in a way that simultaneously fulfills and disrupts the antisemitic imagination. (In one episode, Larry breaks up a baptism; in another, he eats a baby Jesus cookie that was being saved for a nativity scene; in a third, non-Cheryl-related episode, he ends up urinating on a picture of the Christian savior.) And then there’s one of the most high-wire moments of Holocaust humor ever committed to camera, in which a Holocaust survivor meets a member of the reality television show Survivor.

David’s show was never particularly interested in working through any of its thoughts about Jewishness or Judaism. But why should it have been? It’s comedy, not social criticism, and, anyway, it focuses on characters who, intelligent, philosophical even, as they may be, are not what we might call systematic thinkers. The show’s Jewishness was an inch deep and a mile wide, or vice versa. A season-long arc in which Larry confronts the possibility that he is adopted, and therefore Gentile, is genuinely funny but also borders on the reductively essentialist, glorying in the chance to ring the changes on the hoariest Jew/not-a-Jew stereotypes.

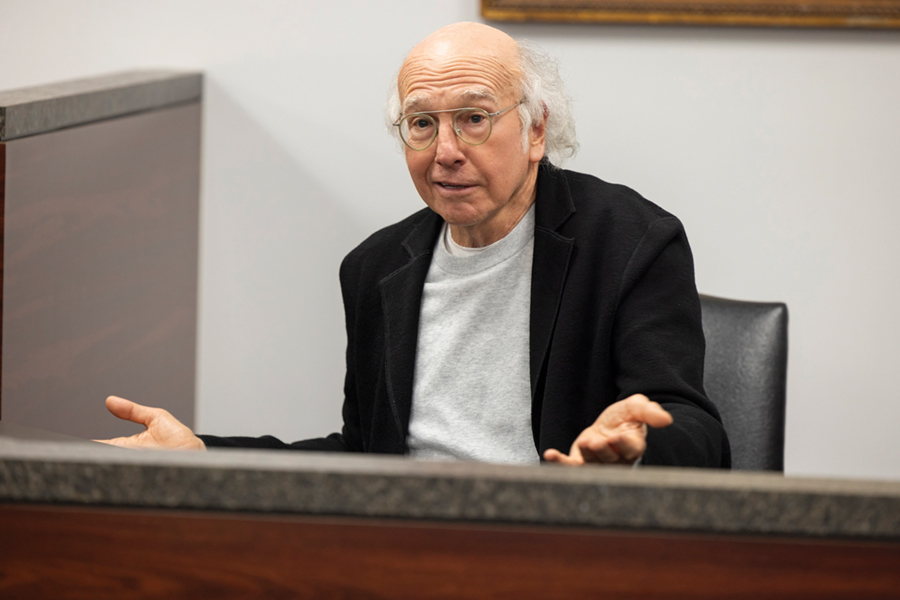

That said, there are elements of Curb that feel deeply Jewish in formal, even aesthetic, terms. Curb’s, and David’s, genius is less about structure, or even situation, and more about improvisation. David is a brilliant performer and the conductor of an orchestra of comedic talent—and repression is rarely the order of the day. Whether he is in a courtroom or on a golf course, Larry is logorrheic. Like Tevye the Milkman or Mel Brooks, he will not, cannot, stop talking, even when common decency and common sense would suggest that it is long past time for him to be quiet. David’s voice, as others have noted, is a remarkable comedic instrument. And it is even more effective when heard in counterpoint to the differently pitched brays of Jeff Garlin and Susie Essman, the staccato punches of J. B. Smoove, or the comparatively laid-back voice of the late Richard Lewis. Unlike most stars, David is happy to let the others shine at his expense, or, at least, at his vanity.

One of the best lines in the history of Jewish humor was delivered by Sigmund Freud, who suggested that Jews are unique in their insistence on making fun of themselves. Theodor Reik elevated this passing idea to a full-blown theory of Jewish comedy as a product of the masochistic impulse. That’s not always true, but it sure works for David. Many Curb episodes, and some entire seasons, culminate in Larry being humiliated, usually publicly. Essman, one of the show’s breakout stars, has become famous for her ability to deliver angry Jewish invective, and although Larry is hardly the only target, he’s certainly first among equals.

Fortunately, on Curb, there’s little real pain and hardly any pathos, because there are no true consequences. The characters are inured to any but the most personal of consequences. Ultimately, nothing is going to happen to Larry David. That’s one of the differences between David’s Santa Monica and Sholem Aleichem’s Kasrilevke.

And it’s fine that the stakes are so low. Really. There is something wonderful about seeing old Jews kvetch on screen in a way that might stir the ire of antisemites but might also take the temperature down a bit. (These guys don’t have time to concoct world conspiracies; they’re too busy counting the minutes to make sure that they can get their egg order in before lunch.) There is also something wonderful about seeing sexagenarians and septuagenarians on screen talking about doctors’ visits and unsightly droops and sags. The show is also a kind of elegy for a certain kind of story, an American Jewish one, which is perhaps, like Curb itself, coming to a close. (The final season is also filled with appearances by Lewis, the American Jewish comedian who passed away not long after the final season was completed.)

If Seinfeld was a show about nothing, a list of the hot-button issues on Curb reads like a laundry list of contemporary preoccupations, including racial tension (remember when, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, a family called the Blacks moved in with Larry?) and political polarization. Indeed, it’s a voting law in Georgia that catalyzes the final season, when Larry risks jail time for giving water to someone in line to vote (accidentally, of course, but he’s happy to embrace all the unearned liberal love that comes his way). And yet Curb’s inclination is to lower the temperature those issues might raise.

Which brings us to the series finale. David, of course, will not let it go—that Seinfeld finale—and honestly, nothing about the Larry revealed to us in these twelve seasons would lead us to expect him to. If he is about anything, it is the inability to let things go, to have minor irritants grow, explode even, from grains of sand to pearls of comedy. The widely reviled Seinfeld finale is the major irritant of David’s fabulously successful career. And so in the final episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, we are presented with another trial in which David head-fakes us into believing that history is going to repeat itself, that he will end up, like his literary cocreations, spending the rest of TV eternity in a jail cell.

But, to quote one of the final lines in the show, uttered by no less than Jerry Seinfeld: “No one wants to see that.” Although the episode is called “No Lessons Learned”—a title that could’ve worked for almost any of the episodes in either show—it turns out that they learned a kind of lesson after all.

As did all their viewers. If the spiky misanthropy at the end of Seinfeld could be interpreted as a metaphor for Gentile hostility and Jewish alienation (it’s hardly coincidental that the Seinfeld quartet is jailed for violating a Good Samaritan law), Curb’s finale turns the antagonism down to a low simmer. Larry poses no threat to society, only to himself: he is eternal in his smallness and, for that reason, invulnerable.

And so the series closes with what, in previous moments and even now, might have been seen as a metaphor for the American Jewish condition eternal: Larry triumphant, querulous, comfortable, and flying back home in first class. But it also leaves us, well, a bit up in the air.

Is David’s desire to insist on an admittedly clever runaround, a return to old and comforting narratives of smallness and harmlessness, enough for his viewers right now? Is that all we want? Well, it’s what David has always been capable of offering us. And, as small things go, it is no small thing.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Great Whitefish Way

Larry David baked an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-meta stance into Fish in the Dark from the get-go.

Of Synagogues and Seinfeld

It's an interesting time to open a museum that argues for the interconnectedness of the Jewish world since it is virtually impossible for non-Israelis to enter the country.

Fleishman Is a Series

Fleishman's real problem is not an acrimonious divorce, but an uninspired adaptation.

History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

On-screen, Mel Brooks was hysterically funny. Off-screen, he could quickly shift to morose or mean.

gershon hepner

CURBING MY ENTHUSIASM FOR LARRY DAVID

It’s very hard to do the right thing all the time,

said a comedic writer-actor David, first name Larry.

Not every error you’ve committed was a crime,

and hopefully the person whom you marry

forgives the ones you make as readily as God

forgave the ones that David in Jerusalem

committed, sparing him as we the rod

we spare when spoiling people whom we should condemn

as if they were just naughty children whose

enthusiasm has caused them to misbehave

because it was uncurbed, but gracefully excuse

as God did David’s when he acted as a knave,

although one thing about him in contrast to Jerry

Seinfeld causes my enthusiasm for him to be curbed,

and instead blow at him a Brooklyn raspberry,

since anti-Zion protests have not publicly made him perturbed.

Roy Goldman

I don't think the author answered the question as to whether Larry David's shows are good for Jews. While I loved "Seinfeld," I avoid watching "Curb Your Enthusiasm" not just because I don't think it's funny, but I also think it portrays Jews in a bad light and promotes Jewish tropes and stereotypes that is not helpful to us.

In a similar vain, I avoided watching "All in the Family" in the 1970's because even though Archie was often seen to be wrong, the show promoted intolerant views held by millions of watchers of the show who probably didn't see him as chastened for his views or saw him wrongly chastened for his view.