The Great Whitefish Way

I bow to no one in my appreciation for the crusty sensibility of Larry David: the arias of minor resentment and aggravation, his enthusiastically masochistic embrace of abuse, and his determination to elevate the quotidian into the realm of the comedically sacred. (In this, he immediately puts to rest any definition of Jewish comedy that locates its sole essence in doing the exact opposite.) And I’m delighted that, in an age where Jewishness on television has become both increasingly visible and increasingly deracinated, he’s been dedicated to exploring—with his own particular idiosyncratic savagery—nooks and crannies of Jewish culture and sensibility you’ll see almost nowhere else.

So I looked forward to seeing David’s Broadway debut, Fish in the Dark, with an excitement shared only by the thousands and thousands who feel exactly the same way. And as such it is with mixed emotions that I report that Fish in the Dark is more interesting as an example of a certain tradition of American Jewish comedy than it is as an entertainment. More precisely, it’s more of an effort to crystallize what Larry David, and Broadway, thinks Jewish comedy has been and should be, rather than an attempt to just get on with the business of comedy, Jewish, or otherwise.

This anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-meta stance was admittedly baked into Fish from the get-go, since both David and his audience were always going to view the production through a glass knowingly. Much of the fun of the production—a fun that has little to do with how well or poorly crafted David’s now-published play is—stems from the fact that we never forget for a moment that this is a Larry David production, by Larry David, starring, at least initially, Larry David. And so we’re constantly on the alert for the iconically recognizable verbal locutions, the syntactic gestures, the bits taken from the alternate universe of Seinfeld or Curb Your Enthusiasm: “We’ve had no ventilator talks . . . Zero! Zero ventilator experience.” For example.

Or the joke revolving around whether you tip a doctor. Or whether you confront your 14-year-old niece concerning the eulogy she may or may not have had assistance in writing. All these bits work in the moment—or at least they “work,” referentially—as we’ve been primed, over the last two decades, to appreciate them as the apotheosis of a certain kind of comedy. But they hardly have the effect of immersing you in a stage-world of its very own.

That world, it turns out, is in some ways a more unfiltered conduit for the Davidian experience than either of the shows that defined it. The poster for the fifth season of Curb Your Enthusiasm depicted a Being John Malkovich-style ocean of individuals CGIed with Larry’s face and the tagline “Deep inside you know you’re him.” Fish in the Dark is an experiment in presenting a world where lots of people get to play Larry David. In retrospect, perhaps this is unsurprising: In Curb Your Enthusiasm, David has the benefit of bouncing off a troupe of skilled improvisers; in Seinfeld, aside from the redoubtable talent of the writers’ room, he had the opposing comedic force of Jerry Seinfeld himself. Here, the writing is all David’s: Imagine a Seinfeld episode that was 22 minutes of George. In fact, I saw the play after David had left to be replaced by Jason Alexander (who had played George)—itself a good meta-joke, but a less-good idea for a play.

It’s hard to blame David, or the show, for that: You don’t go to a Springsteen concert expecting jazz or trip-hop. What might be more surprising is that with the exception of a few gags revolving around particular curse words (one of which served as the basis of a classic Curb episode), once one strips those Seinfeldian bits away there’s little in Fish in the Dark that couldn’t have appeared 40 or 50 years ago, starring, maybe, Phil Silvers (a David favorite). Scratch at the family dynamics, the scenes and settings, and you might get the scent of Neil Simon. There’s a gold-standard archetypal Jewish mother, nasty to the Puerto Rican help, and so overbearing that the play’s plot revolves around her two sons competing to not have her live with them. If Sophie Portnoy ever steps off the pages of Philip Roth’s novel, she’s got a job waiting for her on the stage of the Cort Theatre.

And there’s also plenty of old-school Jewish/goyish fun—including the ever-popular “my mother-in-law doesn’t like me because of the way I set my table” (the grievance that’s the source of the play’s title; “Larry’s” Gentile wife prefers mood lighting to having, in her words, a “house like a Baskin-Robbins”) and the line “You don’t dunk bagels. Who dunks bagels? Goyim.” Even the farcical comic engine—a faked dream visitation for David’s protagonist to try to get his mother to do various things she’s reluctant to do—feels like a homage to the “this I’ll give your Tzeitel!” sequence in Fiddler on the Roof.

Broadway, of course, is hardly the place to look for cutting-edge anything. With ticket prices this high, producers aren’t looking for avant-garde experimentalism. But that’s not the issue here: With David writing and starring, he could have stood center stage in his golf shirt and yelled at the audience for 90 minutes and the producers would have recouped.

On the other hand, David has always, always been an old-school sentimentalist when it comes to Jewish comedy under that alienated (and alienating) shell. He cast the breakthrough 1950’s comic Shelley Berman as his dad on Curb and dedicated an entire season to a joke that’s essentially a footnote to The Producers. (A brilliant, brilliant footnote, in which David makes a pre-Fish “live stage debut” in order for Mel Brooks to attempt—and fail—to sink a show.) His ambitions appear to be those of an older generation of Jewish comedians: Brooks, Reiner, and Allen (rather than, say, Sandler, Apatow, and Silverman)—an age when making it to “the Great White Way” was the mark of real showbiz success. And his ideas for what Broadway should look and sound like hark back to the 1950s and 1960s as well. Yes, we’ve seen these moments before, and before, and before, but that’s because David has such an unexpectedly unironic sense of what it means to write a stage comedy. For someone so anxious, the anxiety of this kind of influence concerns him not at all.

All of which might explain why it’s not such a shock to find that Fish overturns Seinfeld’s dictum of “no hugging” so sincerely. Admittedly, the final scene has some elements suggesting the characters won’t change entirely, but the curtain’s fall rings of closure far more than of discomfort. A bunch of well-wishers are ranged around the mother’s hospital bed, their clenched fists turning into fist bumps, as she looks up, literally knowing best.

This sort of thing would have been the subject of savage mockery on Seinfeld. But Larry David’s deep love for an earlier seam of American Jewish comedy—Borscht Belt, Broadway, and television’s early days—means that when he turns to this medium the results, if surprising, are unsurprising.

Suggested Reading

Her Own Creation and Pure Luck

The fraught project of becoming an American pulses through Susan Rubin Suleiman’s memoir, along with the similarly fraught project of becoming an adult.

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

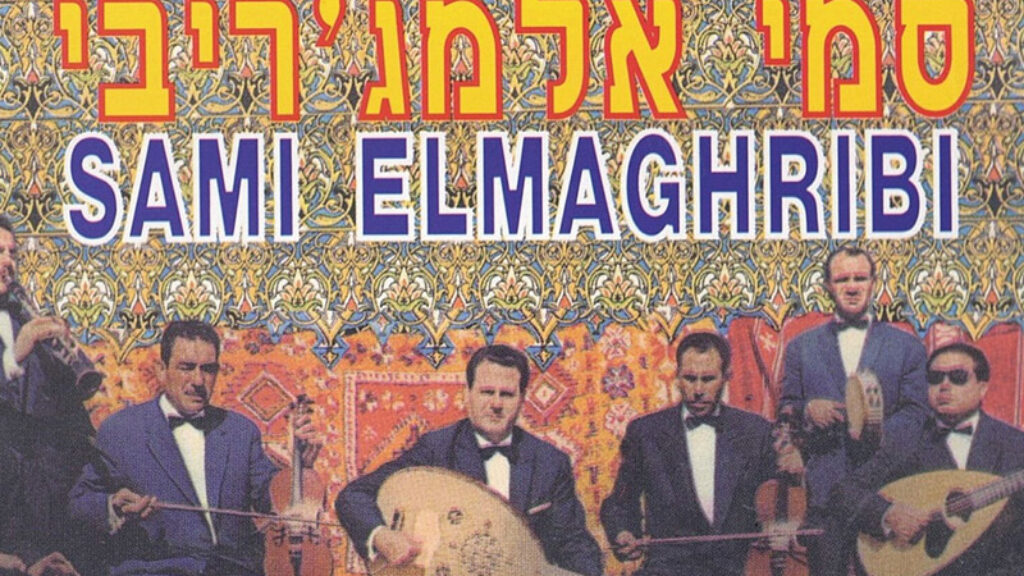

Missing Notes

There was a time when Jewish artists set the tone for North African music, but now only echoes remain.

Sundowning

In Morningstar Heights, Joshua Henkin tells his story simply and directly, with a narrative economy that conceals much close observation and human understanding. These have always been the strengths of his work, though they are not the qualities best rewarded in contemporary American fiction.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In