Of Torahs and Children

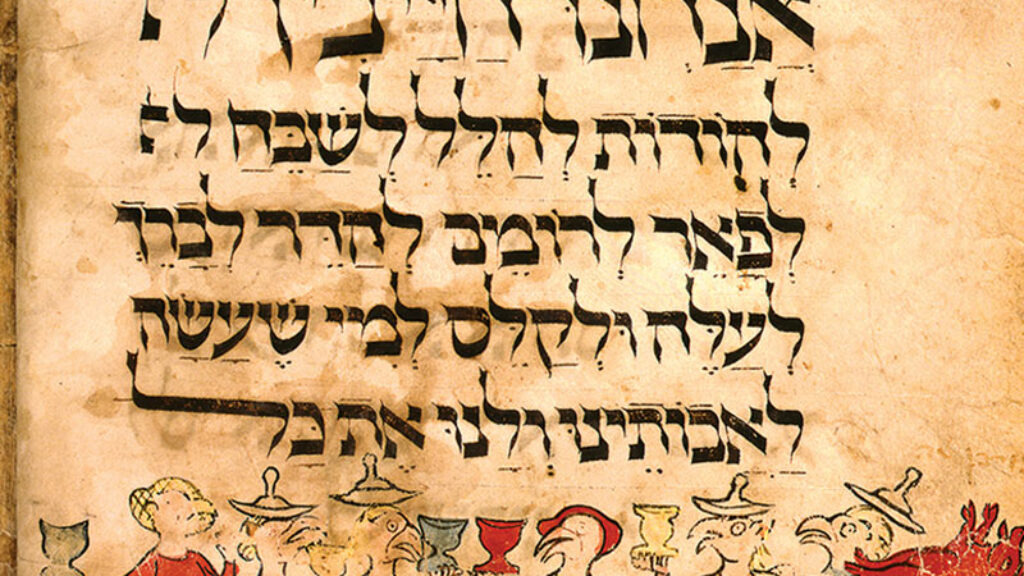

Sometime in the late 1970s, I visited Beit Hatfutsot (Museum of the Diaspora, now called Anu—Museum of the Jewish People) in Tel Aviv. One of the exhibits was a diorama of a family scene from early modern central Europe that dramatized the making of a wimpel, an often lavishly decorated linen sash that was wound around a Sefer Torah several times as a binder. The minhag of that time and place was to make it out of the swaddling cloth used for a baby boy during his circumcision. After the brit, the linen was cut into strips, which were sewn together and embroidered or painted by the mother and women of the family with the name of the child and his father. Often, the traditional blessing was included: just as the child has now entered the covenant of Abraham, so may he grow up to a life of Torah, chuppah, u-le-ma’asim tovim (Torah, the bridal canopy, and good deeds).

I had heard of this custom before, but the visual symbolism of it struck me powerfully, especially because the word used in most of the text accompanying the exhibit was not the Yiddish wimpel, but chitul, the common Hebrew word for “diaper.” The imagery plus the text made this ritual more vivid—and anthropologically interesting. The fact that the body of a baby boy was being symbolically identified with the scroll of the Torah at his first rite of passage seemed like it might reveal something not only about the values of Western Ashkenaz but about deep structures widespread in Judaism itself that were not always made explicit.

I had, like many cultural anthropologists at the time, read Victor Turner’s The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual, which explicated the deep symbolism of circumcision and other rites in a central African society, and I saw that in this Ashkenazi custom I could approach Jews as Turner had approached the Ndembu. In 1980 Turner gave the keynote address at a meeting of the Israeli Anthropological Association, and some of the papers eventually appeared in the volume Judaism Viewed from Within and from Without. My contribution was on the symbolism linking the Torah and children, a subject that I have been thinking about ever since.

The wimpel exhibit, that day at Beit Hatfutsot, had made me think of the well-known custom of dancing with both children and Sifrei Torah on the holiday of Simchat Torah, the celebration of the completion of the Torah cycle at the end of the fall holidays. I had participated in and seen this in synagogues all my life, but the symbolic significance of dancing while holding the Torah and dancing while holding a child had not occurred to me until I thought deeply about the Central European minhag of binding the Torah with the baby’s circumcision cloth. Why were Torah and children paired? How did the central ritual object of Judaism become associated with the male child?

Possible answers were not long in coming: education and reproduction, or, in the traditional threefold formula embroidered on the wimpel: Torah, the wedding canopy, and good deeds. Torah (and the life of good deeds it teaches) embodies the education that ensures cultural continuity, and the child, produced by the couple established under the wedding canopy, embodies the biological continuity of the people of Israel. The transmission of the Torah and the procreation of a Jewish child are symbolically identified in these rituals.

This is not to say that this identification was ever an explicit doctrine of Judaism, nor does it occur in every time and every place, but it does surface in various ways both in Ashkenaz and in North African Jewish communities I have studied. The intertwining of biological and spiritual continuity through the personification of Torah or the scripturalization of the Jew can be discerned in the practices of many Jewish cultures once one is alert to the phenomenon.

A striking instance is the medieval Ashkenazi school initiation ritual that Ivan Marcus discussed in his influential 1996 book, Rituals of Childhood. On Shavuot, which, by tradition, commemorates the giving of the Torah at Sinai, young Jewish boys were wrapped in a tallit and carried by their fathers to the teacher—just as a Torah would be carried. They were then induced to lick honeyed Hebrew letters from a slate and plied with delicacies inscribed with verses. We reenact the Torah’s reception at Sinai and initiate the child into his formal study through rituals that situate him as a metonym for the Torah itself.

Victor Turner had emphasized that dominant cultural symbols are characterized by two intertwined poles—an ideological one, focused on the central values of the society, and a sensory, or sociobiological, one, which anchors symbols in the life and emotions of individuals. Binding a Sefer Torah with the swaddling cloth of a circumcised baby boy, carrying a young boy as if he were a Torah, feeding him letters and verses, and dancing on Simchat Torah with a child as if he were a Torah (and a Torah as if it were a child) are all powerful ways of anchoring Judaism’s values within the life of its adherents. Turner’s model sensitized me to aspects of Jewish experience that I had not paid enough attention to. For instance, the refrain of a popular Simchat Torah song repeats a famous kabbalistic phrase: “Israel [the Jewish people], the Torah, and the Holy One Blessed Be He are One.”

Simchat Torah identifies the perpetuation of the Torah with the perpetuation of the people of Israel in another striking way. After the dancing is over, the men who are honored to be called up to the Torah are called chatanim, or bridegrooms, of the Torah. Perhaps even more revealing, all youngsters (kol ha-ne’arim) are called up to the Torah together with a distinguished member of the congregation as their adult representative. A large tallit is spread over their heads like a bridal canopy. Then Jacob’s poetic blessing of Joseph’s children Ephraim and Manasseh is read from the first book of the Torah:

The angel who has redeemed me from all harm—bless the lads.

In them my name be recalled.

And the names of my fathers Abraham and Isaac,

And may they become teeming multitudes upon the earth. (Gen. 48:16)

The children assembled before the Torah scroll are teeming multitudes of which it speaks; it is through them that the Torah lives—and vice versa.

Suggested Reading

(Almost) People

What does it mean to say that books have lives?

A Tale of Two Night Vigils

The tradition to stay up all night studying on Shavuot is far more well-known than the tradition to do so on Hoshana Rabbah. Neither would have been possible without Kabbalah and caffeine.

Underground Man: The Curious Case of Mark Zborowski and the Writing of a Modern Jewish Classic

Life is with People is perhaps the most well-known work of shtetl nostalgia. But how should it be read in light of its author's bloody career as one of Stalin's best spies?

The Treasure of the Jews

The seductive idea that the real Jerusalem lurks somewhere beneath the actual city, with its grocery stores, traffic, and inconveniently present residents, has motivated archaeologists and journalists since the 1800s.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In