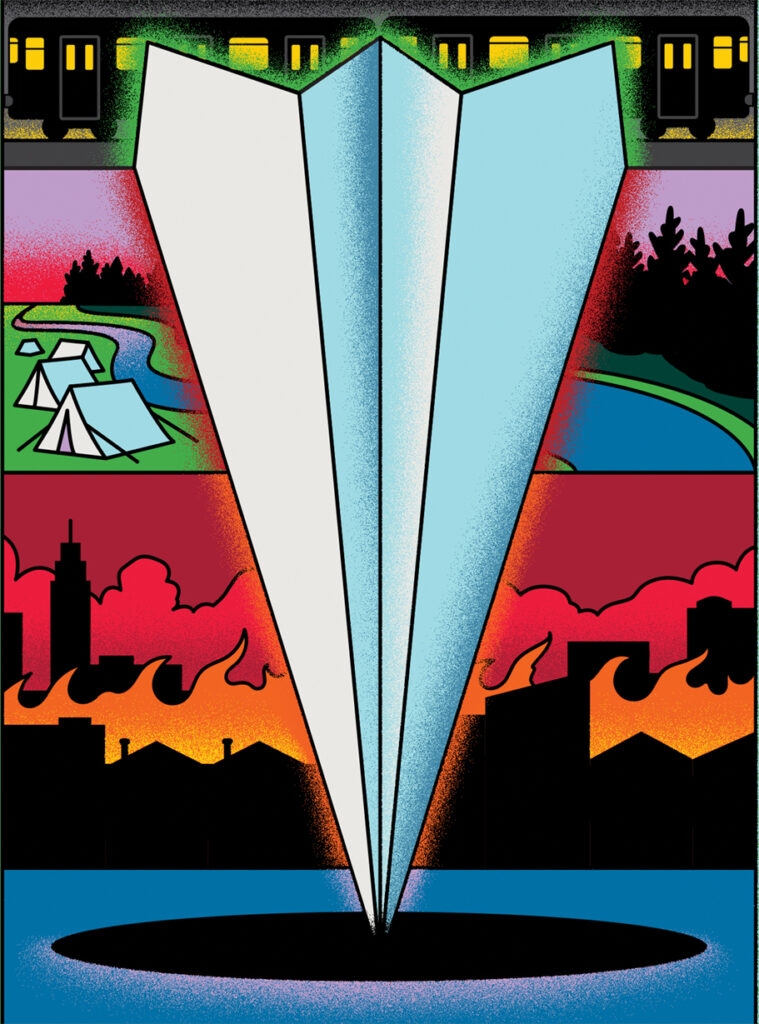

Boy Meets Girl Meets Apocalypse

The destruction of the State of Israel has never been so popular. Murderous Hamas terrorists infiltrate the country, Iranian and Hezbollah rockets blanket the sky, student protestors call for intifada, and American Jewish writers turn the land over to welter and waste. Or a black hole. In Benjamin Resnick’s debut novel, Next Stop, Israel vanishes completely—swallowed up by a gaping maw termed “the anomaly.” Set twenty-odd years after this apocalypse, smaller anomalies now speckle the world, sending countries spiraling into crises and exerting a strange pull on Jews, some of whom pass through the holes to a mysterious other side.

Next Stop is the most recent entry in an odd and perhaps revealing microgenre. American Jewish novelists have been writing about Israel for decades, but the surprising impulse to destroy it is relatively new. Philip Roth toyed with the idea in a metafictional way in his 1993 novel Operation Shylock, and Michael Chabon, Jonathan Safran Foer, and Joshua Cohen have each, in different ways, dramatized it in the years since.

In Resnick’s novel, the appearance of the anomaly in America causes authoritarianism and legalized antisemitism to spread, but life goes on. In an unnamed city that’s clearly New York, Ethan Block, an unaffiliated Jewish writer, falls in love with Ella Halperin, a Conservadox single mom. Ethan, a shy loner, finds himself enveloped by Ella’s family: her precocious six-year-old son, Michael; her religious friends and parents; and her radical-terrorist sister.

As the anomalies grow stronger, restrictions on Jewish life and movement grow worse, and Ethan and Ella try to maintain normal lives in the city and then in the Jewish ghetto known as “the Pale”—a hint that the novel’s main concern is really in the diaspora. In this new Pale, flashes of the old world (though never Israel) appear in surreal apparitions—lost grandfathers, diners from a previous age, mystics—and a new world of scrappy American resistance fighters take charge of the situation.

Relationships in this new Jewish reality are strained and so, unfortunately, are Resnick’s skills as a novelist (a sex scene feels like the author was embarrassed to write it, and the dialogue is often stiff). Where he is strongest, however, is in building a world around his outrageous allegorical premise.

It’s an age of miracles—a bucket of tomatoes replenishes itself, trees bloom suddenly, a child grows ten years in a morning and returns to youth by the afternoon. The black holes are random, eerie, and intriguing. The original anomaly has a particularly strange effect when Jews approach it:

Sometimes the pull of the anomaly was overwhelming and the Jews wound up running themselves to death through the desert . . . the children trailing behind their parents and expiring first and the parents in their delirium, not even turning back. What drove the Jews to such madness?

Jews are simply different in Resnick’s world, and everyone knows it. As one Gentile character says, “It is strange, though, that everyone seems to be able to spot a Jew these days. . . . Ever since the First Event.” This inability to pass makes antisemitism inescapable, leading to Jewish defense leagues that spend their time “in the south building bombs and printing ghost guns.” At a Passover Seder, Ella’s sister declares, “I’m not going to let us end up like those sheep in Europe. . . . I’m going to die fucking fighting.”

Fighting—in word or deed—against Jewish catastrophe animates much of the little genre, to which Next Stop belongs. In Operation Shylock, Roth faces a bizarre doppelgänger who looks like him, sounds like him, and even has a passport in the name of Philip Roth. This man—whom our Roth calls by the Yiddish joke name “Moishe Pipik”—runs amok advocating “diasporism,” an ideology that calls for Jews to leave Israel and return to their homelands in Europe. Why? Because Israel has “become the gravest threat to Jewish survival since the end of World War Two.” The ingathering of exiles has put them all at risk for a great wipeout—not by an antisemitic black hole but by something just as cataclysmic for the Jewish people.

Roth confronts the “imposter in Jerusalem” but then finds himself posing as the imposter and bombastically arguing for the superiority of diasporic Jewish culture, over the self-satisfied machismo of Israeli Jews:

I took more pride, I told them, in “Easter Parade” than in the victory of the Six Day War, found more security in “White Christmas” than in the Israeli nuclear reactor. I told them that if the Israelis ever reached a point where they believed their survival depended not merely on breaking hands but on dropping a nuclear bomb, that would be the end of Judaism, even if the state of Israel should survive. “Jews as Jews will simply disappear. A generation after Jews use nuclear weapons to save themselves from their enemies, there will no longer be people to identify themselves as Jews. The Israelis will have saved their state by destroying their people.”

In narrative context, Roth is bluffing, but what seems to animate both the speech and the novel is not fear for the survival of the Jewish people; it is fear about the waning of American Jewish culture.

We can see the same fear animating Resnick. There is not really any grief expressed over the loss of Israel and all of its people in his novel. This description of the Pale is the closest we get:

There were Jewish separatists and new-Zionists; secularists who advocated for working with the city authorities; Israelis who had been abroad during the First Event and who observed Yom Ha’atzmaut as a day of mourning; militants who advocated for an uprising; orthodox rabbis who advocated quietism and acceptance, as they had centuries earlier; ba’alei teshuvah, the newly religious who preached about God’s wrath and about repentance and fasted on Mondays, Thursdays, and Sundays.

There are no other indications of mourning in the novel. In the broader narrative, Israel’s loss isn’t an emotional tragedy because it returns pride of place to the thriving energy of diaspora communities. Israel’s existence prevented this. What seems to motivate Resnick as a novelist (he is also the rabbi of the Pelham Jewish Center in New York) is American Jewish anxiety over Israeli influence, the fear that we American Jews don’t matter much in a world in which Israel thrives. The one place he allows Israelis in his novel to succeed is as macho fighters who train their American cousins.

Jonathan Safran Foer explored the fear of Jewish American irrelevance in his 2016 novel Here I Am. Foer’s narrative stand-in Jacob Bloch is a writer dealing with a disappointing career and a collapsing marriage when Israeli relatives visit for his eldest son’s bar mitzvah. Amid the family dysfunction, a cataclysmic earthquake destroys much of Israel and parts of the Middle East, leading to war and the near destruction of Israel. At one point during the crisis, his tough cousin Tamir rants:

“Your children are asleep on organic mattresses. My son is in the middle of that,” he said, pointing at the television again. . . . “You want to be part of the epic, and you feel entitled to tell me how to run my house, and yet you give and do nothing. Give more or talk less. But no more referring to us.”

Foer didn’t completely destroy Israel in his novel, but he cut ties with it, turning Israelis into disinherited Esaus and American Jews into Jacobs—the real Israel. “Israel survived,” he wrote, “but neither Israelis nor American Jews could deny what was exposed”:

What was Israel to him? What were Israelis? They were his more aggressive, more obnoxious, more crazed, more hairy, more muscular brothers . . . over there. They were ridiculous, and they were his. They were more brave, more beautiful, more piggish and delusional, less self-conscious, more reckless, more themselves. Over there. That’s where they were those things. And they were his. After the near-destruction, they were still over there, but they were no longer his.

Back in Resnick’s world, Ethan and Ella feverishly follow the news of a fresh disaster—the world’s planes get sucked into the big Israeli anomaly—in one of the best passages in the novel:

Japan and New Zealand close their borders. Refresh. A post from a famous actor, on location in Croatia, sheltering with his wife, sending hopes and prayers. A bomb in Moscow. A bomb in Zagreb. Refresh. A bomb in Cairo. Refresh. Refresh. Probes enter the Exclusion Zone in the Middle East. No data. No data. Refresh. No data. Refresh. No data. Refresh. Refresh. Checkpoints at European train stations. China closes its borders. Italy closes its borders. A recording artist asks a simple question: What’s in it for the Jews? Could someone explain? Refresh. The recording artist retracts. She apologizes to anyone whom she offended. The king of England urges calm—Brits will soldier on. France stands ready, #LibertéEgalitéFraternité. Reports of unrest in Buenos Aires. Refresh. Report: Concerns about the security of the Pakistani arsenal. Refresh.

Moments like these are harrowing, capturing the fear and loathing we have all felt in compulsively refreshing the news—COVID-19 (a key influence on Resnick’s novel), the Gaza War, the campus protests, the 2024 election, etc.—over the last few years. But despite these moments and the boldness of the novel’s premise, the story it attempts to tell is not fully baked. How does the anomaly lead to a bomb going off in Zagreb? Why are there roving militias? Who exactly are the Jews fighting? Not all details need to be spelled out, but a few more would be helpful if the events lead to Jews being herded into ghettos.

In place of plausible narrative, Resnick relies on imparting a distant, fairy-tale quality to his prose. He doesn’t, for instance, name any cities. Tel Aviv is a city “in the Middle East.” London is “an island city.” A conspiracy theorist who posts his rants is “the Man on the Island.” But this distant tone can make for a confusing read. A strange man in the Pale declares himself the messiah, but what does that mean? What does he do? For most of the novel, not much, until, of course, the end.

“From Egypt all of the people went free,” Ella’s father explains one day. “But only the children entered the Promised Land.” The single most animating factor for Ethan and Ella is taking care of her child, Michael. They work to keep him happy and safe as they adapt to ghetto life and struggle to decide whether to risk passing through the nearby anomaly in the subway station. Even as adult life collapses, the children of the Pale adapt quickly:

For the younger ones, life in the Pale was remarkably normal at first and in some ways more pleasant than it had been before. They made friends. They learned to read. They started learning to code. They went to school, just as they had gone to school before, only the children and teachers were nicer to them. They did not understand, at first, that the lives of the adults around them had changed radically. They only knew that now everyone lived together, grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins.

Watching Michael play outside one day, Ella thinks, “Here is the creation of the world.”

As conditions worsen in the Pale, more Jews descend through the anomaly, but it terrifies Ella to think about what might be on the other side and the possibility of losing Michael. When Ethan, Ella, and Michael walk by the self-proclaimed messiah and his followers, they realize that the crowd is floating away into the sky:

Overhead, the messiah flailed wildly and screamed something in a language that nobody knew. But it was not until several seconds later that they realized he was falling up. Soon after that, a few others joined him in his ascent.

Michael began to float away as well, until Ethan and Ella “dragged Michael from the sky with all of the force they could muster, their fingernails digging deep gashes into his arms.”

In The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Michael Chabon didn’t destroy Israel; he aborted it. In his alternate history, Israel lost the War of Independence, and the fledgling state was crushed, helping give rise to a vibrant Yiddishland. The novel is set in Sitka, Alaska, in a fictional district loaned to refugee Jews in the 1940s, where Meyer Landsman, an alcoholic detective, works to solve a murder and uncovers a sinister plot to return Jews to Israel with the aid of some light terrorism, heavy real estate corruption, and a chess-playing drug addict named Mendel Shpilman who can perform miracles. Shpilman, the would-be messiah, foils the plot by organizing his own murder, which makes him the hero, even savior, of the book, if not the messiah. Landsman (whose very name ties him to the exile), and, by extension, Chabon, has absolutely no interest in being redeemed and taken to the Holy Land. He declares in the book’s most famous line:

I don’t care what is written. I don’t care what supposedly got promised to some sandal-wearing idiot whose claim to fame is that he was ready to cut his own son’s throat for the sake of a hare-brained idea. I don’t care about red heifers and patriarchs and locusts. A bunch of old bones in the sand. My homeland is in my hat. It’s in my ex-wife’s tote bag.

Joshua Cohen’s Witz took the messianic idea more seriously, but it had less impact than the novels of Roth, Foer, and Chabon for a few reasons: It was published by a small indie press, it’s eight hundred pages long, and it’s fairly unreadable, if also sort of brilliant. The dense, meandering plot, insofar as there is one, is set in motion by Jewish mass death.

On New Year’s Eve 1999, every Jew in the world dies, save for the firstborns, including Benjamin Israelien. In a world of endless winter and New Jersey, the firstborns are rounded up and surveilled, but all soon die except for Ben, who is named the messiah, a title he rejects. It’s a novel far more interested in wordplay—“deadication,” “Yankels and Metz,” “Palestein,”—than in narrative; it invites many interpretations and resists all of them. What Witz did successfully conjure is a distinctively Jewish, and distinctively diasporic, anxiety.

As conditions worsen and pogromists rip through Resnick’s American Pale, staying becomes untenable, and Ethan, Ella, and Michael finally descend through the local anomaly to a kind of purgatorial subway system. Jews from all over the diaspora and across the centuries congregate and wait for a train to arrive and take them to the next stop. They wait in the dark for months, slowly adapting yet again in the way that Jews do. (Where the Israelis ended up when they passed through their anomaly, nobody knows.)

Michael attends a makeshift underground school until the messiah reemerges, and in the ensuing chaos of his revelation, a train finally arrives. Michael, though trying to cling to his mother, finds himself absorbed by a flow of boarding children. After doing everything to keep Michael safe, Ella can no longer hold on to him:

She had made her decision but still she did not let go. She had him. She had him. She had him until the moment she did not, when the little vessel of their family finally broke and he was carried away from her.

It’s a stunning and unexpectedly moving conclusion to their family story. Early in the novel, Ella thinks, “It felt as though their lives were racing ahead of them but that they had been somehow stranded in the past, like an outdated piece of technology, a plug that no longer fit any outlet.” In the end, the old are stranded, and only the young will enter the land, boarding this otherworldly Kindertransport.

Foer’s novel was curiously silent about Jewish children. Although so much of the novel concerns Jacob’s three sons, they’re mostly around for tragicomic relief, not to signal much about Jewish continuity. In The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, an abortion ruins a marriage, but the novel has little concern for the future, believing only in the eternal Jewish now of herring and Yiddish jokes. And Philip Roth’s main concern was, well, Philip Roth.

In Cohen’s Witz, after all the Jews die, the Gentiles declare themselves Jews—or “Affiliated,” to use the novel’s term—but they also consider cloning Benjamin to have a properly Jewish woman for him to marry and continue the Abrahamic bloodline. Cohen muses about Jewish survival, pointing out a paradox of assimilation and matrilineal descent:

Prior to the tragedy that’d occurred . . . many had thought that intermarriage, which is the marrying between different people, races, religions, would destroy the Affiliated, diluting the blood with another bodily fluid. But, as our scholars remind us, since the blood of the dead has always been transmitted through the mother, at least according to the Law theirs and ours, it’s in truth impossible to sex us out of our birthright, no longer chosen.

Aside from being one of the more readable passages in the novel, Cohen is making fun of “the Law” while still caring about it. The final hundred or so pages shift dramatically to the last living Holocaust survivor who recalls his picaresque life as he slowly dies alone. One thing Cohen seems to be saying, if I can be so bold, is that each generation’s death is the death of a whole world, leaving those newcomers no more recognizably Jewish to the past than Cohen’s slapdash postapocalyptic converts. Benjamin Resnick’s outlook is nominally more hopeful—not every generation is doomed, only this (fictional) one.

In Operation Shylock, Roth works himself into an entertaining rage over a future still dogged by his Israeli doppelgänger, Pipik:

Even worse than never being free of him, I’ll never again be free of myself; and nobody can know any better than I do that this is a punishment without limits. Pipik will follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of Ambiguity forever.

Resnick and his literary predecessors all suffer from a restless ambiguity. They can never be free from Israel—from the sense that Israelis are stronger than them; or ruder than them; or more destructive, innocent, genuine, maddening, brilliant, and Jewish than them. Nor can they be confident that they really do dwell in a land where their own brand of Jewishness is worthwhile and urgent enough to be passed down. These fears stalk our fiction, and I suspect that they will continue to do so.

Suggested Reading

A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

Despite all of Bob Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he really was a child of the American heartland. Winning the Nobel Prize might actually be his most Jewish achievement.

Michael Chabon’s Sacred and Profane Cliché Machine

What's wrong with "knocking down walls"? Well, several things...

Distant Cousins

None of these four novels by American Jewish writers is fully at home in Israel—they’re more like Mars orbiters than rovers.

The Language of Babylon

The Jewish scholar of Arab literature Sasson Somekh's new autobiography is the latest in a line of memoirs of Jewish Baghdad.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In