“I’m Eighty-Five Years Old, Bubba’leh”

“No-no-no-no-no-no! Not there. Lower . . . lower. There! Lower. No, boys! It’s hiding the thingy. Yes. Oh, yes. Like that. Yes. Yes. A little to the right. More to the right. To the right! To the right. Not your right, my right. That’s better, eh?

—“You see, Hannan, this was Paulina’s favorite painting. A Mordecai Ardon reproduction, blue with orange squares, a bent shofar. We bought it at the Tel Aviv Museum, I can’t remember when. . . . Excuse me.

—“No, no, now you’ve made it crooked again. A little to the left. Hang on, let me back up. Straighten out that corner. That’s it! That’s it. Don’t touch it, it’s perfect.

—“So now, sit right here. . . . The truth is, I debated whether or not to hang the painting here. After all, Paulina got it for our home, not for my office here at the institute. But this morning, when those nice boys came over and took the painting off the foyer wall, they left a white square behind, a monument to Paulina, and I thought that this enormous square, this white, naked discoloration right across the way from the kitchen, reminded me of her, of Paulina, aleha ha-shalom, much more than the painting, which I’d grown used to, and to which my heart had hardened. So here it is, proudly overlooking my Israel Prize, my rabbinical certification which has turned yellow, the 2007 Jewish Book Award, which we went to New York to receive. That was the last time we visited. Since then it’s been hard for me, and well, yes, there’s more, but that’s for another time.

—“Yes, we’re finished here. Thank you, thank you. Take care.”

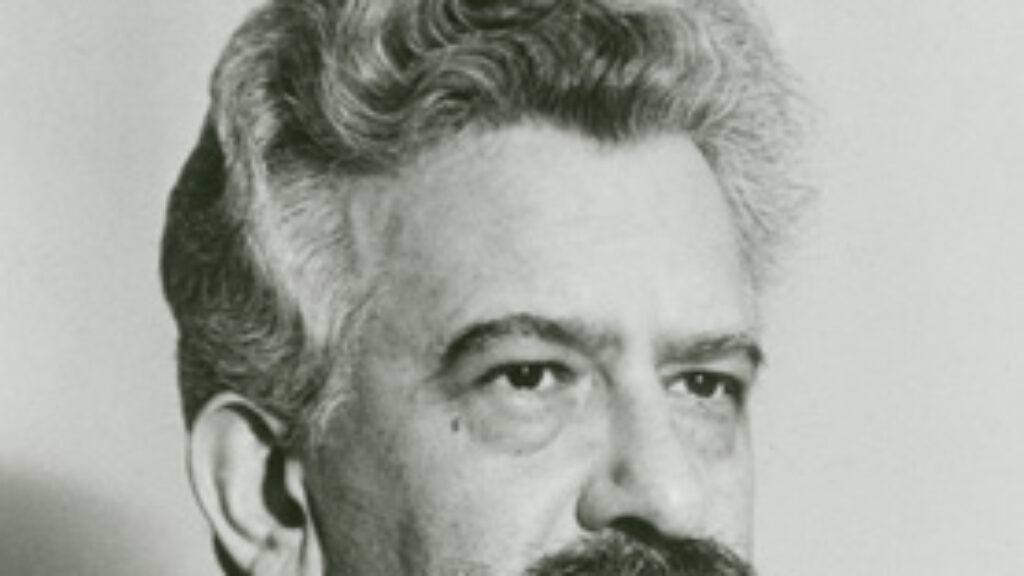

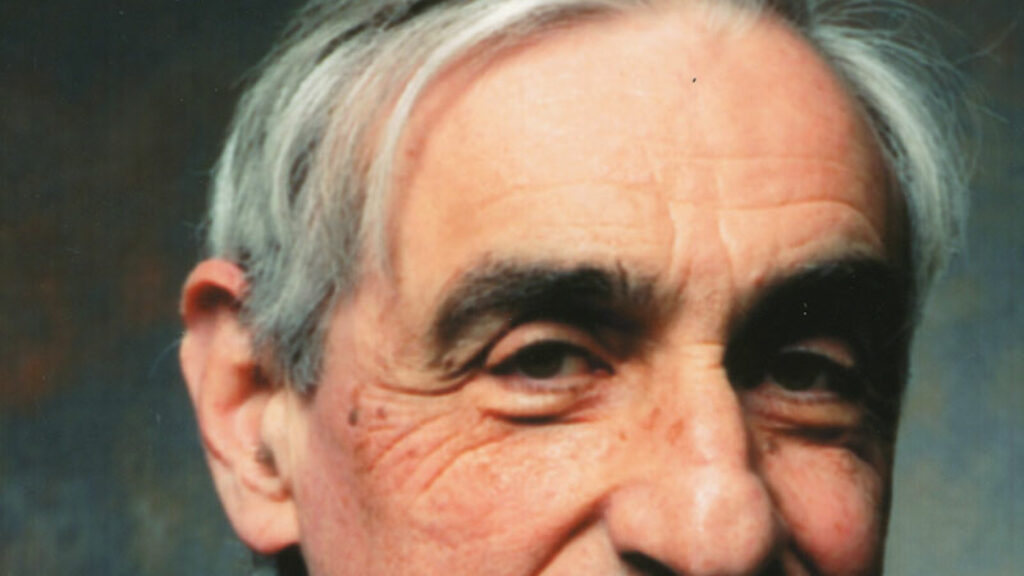

“Where was I? Mordechai Yavin-Jesselson, that’s my name. Feel free to also call me ‘Rabbi’ or ‘Professor.’ Neither offends me. No, not ‘Motti.’ Never ‘Motti.’ If you want to call someone Motti, why don’t you go downstairs and talk to the guy at the corner store? For years, people referred to me as Professor Jesselson. The old-timers at the institute, those who’d been here from the start—some came over with me from Cincinnati, others attended Brownswood Yeshiva with me, I’m talking about the mid-1950s—call me Marty, but they are dwindling, dying out. Just last week I went to Bernie Auman’s funeral. He worked in the office across from mine for forty years.

“Rabbi? Paulina used to call me ‘rabbi’ sometimes, as a gesture of love and humor. Here in the neighborhood, if people refer to me as ‘rabbi’ it gives me chills. All I can do is hope they don’t bother me with halakhic questions about electric razors or worms in their lettuce or God knows what kind of narishkeit the Orthodox worry about these days. But honestly, how often do I walk around on the street anymore? I’m eighty-five years old, bubba’leh.

“A glass bookcase at the lobby of the institute features every single book written by our scholars, including my books—I’ve written six and I love them all. I love them almost as if they were my children. Six books. That’s not nothing. A fine number. Some of them have even won awards. I’ve toiled over each and every one of them, and now I’m writing the last one. Once I finish it, there will be no more. A memoir. An autobiography. The story of my spiritual and intellectual journey—from my childhood in Brooklyn through my university studies, my rabbinical certification, making aliyah, founding the institute, and everything that came along with it. I might also write about Paulina, our family, thoughts of the future, about what’s going to happen after I’m gone, I don’t know yet.

“I write every day. I wake up around six, glance at the picture of Paulina by the bed—young and beautiful, that’s how I want to remember her—eat a piece of toast with cream cheese, and drink coffee. Sometimes I pray. Not always. The truth is, I haven’t wrapped tefillin in a while. I’ve grown tired of it. But occasionally I still pray softly at the window overlooking the Judean Desert, with the stunning, indulgent breeze—a breeze every day of the year, in every season and in any kind of weather.

“Then I grab my papers, slip on my suspenders and my jacket, and walk to the institute the next street over, where I write until the early afternoon. When I get fatigued, I go home for a nap. I come back around four o’clock, walk through the rooms, teach a class in the beis midrash, meet with one of the scholars or participate in administration meetings led by Haviva, whom I’d appointed head of the institute five years ago—a bright, young, trustworthy woman—and then I read through what I’d written that morning.

“Just before sunset I go home, put on a record—the music I grew up listening to, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra—and think about Mom and Dad. Mom, who danced with us in our tiny apartment in Crown Heights, and Dad, Joshua Jesselson, who fought in World War II and returned quiet and hurt—I was eleven years old when the war ended.

“And so, I drink a glass of cognac in front of the setting sun and rejoice in the fact that another day has ended and I’m still here.

“There it is, the famous photograph from Aachen, Germany. Dad is looking sideways, a small siddur in his hand. To his right is Max Fox, rifleman and cantor, with a tallis, siddur, and a confident gaze, shoulder to shoulder with the chaplain, Sydney Lefkowitz, the Army rabbi, caught in the middle of davening on German land in October 1944—possibly the first public Jewish prayer in Germany since Hitler rose to power. It was broadcasted on the radio and talked about all over the world—the prayer and Lefkowitz and Fox, and by his side, silent and proud— my Dad. Dad, who wanted to fight against antisemitism but also just to flee, flee everything—Crown Heights and us.

“And what about me? Where was I at the time? Was I playing basketball in the schoolyard or was I home with Mom, who enveloped us with love and warmth as we sat together, missing Dad, who was pausing to daven at that very moment, and caught by a photographer’s lens.

“When Dad returned, everything got worse: he drank like a fish and couldn’t hold down a job. I, the oldest of four, followed in my father’s footsteps and ran away—not to the army but to Brownswood, a black-hat yeshiva, and from there to a Modern Orthodox yeshiva, and from there to college.

“Then I got a phone call in the middle of the night, telling me that Dad had died. He’d gone to sleep and never woke up. I came back to Crown Heights to bury him and say Kaddish. At the end of that year, 1960, I married the woman I would spend fifty years with, until she died on me too. Paulina.”

“Two years after our wedding, we had a son. At his bris, in a little Manhattan synagogue, we named him Yehoshua Binyamin, after Dad, in spite of everything. Yehoshua Binyamin Jesselson, who went by Josh, Josh Jesselson. A tall boy who looked nothing like me and took after his mother with her Slavic beauty, her delicate features, her good posture. After that we had three daughters, but Josh—I have to say it here, the thing I wouldn’t dare write in my book, even though it’s the truth—I loved Josh the most. He was my might, the first sign of my strength, excelling in honor, excelling in power, as Jacob said of Reuben. We’d sit together with the big Chumash with the green cover and the thick letters and read together through the tales of Joseph, Bnei Yisrael in the desert.

“In 1969, when Josh was seven, we moved to Israel during the big post-Six-Day-War American aliyah boom. As Josh got older, we continued to learn together. He would walk into my office at the institute and ask me about faith and providence and prayer and all the big questions that I taught at the institute and the university and wrote books about. With age, it became clearer to me how nearly unanswerable those questions really were.

“Josh and I would talk and study together in my office—not here but at the old institute building, not far, in that stone house that has since been demolished, just as the rest of Talpiot had transformed since I’d arrived here in the early 1970s. We spent hours upon hours together, Josh and I. Then he went to yeshiva, and planned to get a BA in Jewish thought.

“I recognized my younger self in him—the confused religious boy, immersed in the teachings of his ancestors but blasted by the force of modernity. That’s who I was, too. I also recognized, if I may be so bold—I won’t write that in the memoir either, I’m revealing my deepest secrets here . . . before Ardon’s shofar—I recognized my own spark of brightness and intellectual fervor, even if the years had dulled it. Josh managed to get one year of university under his belt. Today, all I have left is myself, still blue-eyed but walking with a cane, a death, bitter, dabbling in heresy, but more than anything, lonely.

“There is no easy way to tell this story. In my book, I struggled with this chapter for days and nights before finally recording the dry facts, as if they were nothing more than a small news item in the Jerusalem Post. Josh—Yehoshua Binyamin Jesselson—our beloved oldest son and a wonderful brother to his three younger sisters, a standout guy and a student of Jewish thought, was killed in a traffic accident on the Coastal Highway at age twenty-four. On a Saturday night in summer 1986, he and his friends returned from Haifa after spending Shabbat at the home of their rav from yeshiva. A truck driver, asleep at the wheel, veered out of his lane, and crushed Josh to death.

“The phone rang in the middle of the night. We were called to the hospital, where we were told he was dead. Oddly, we didn’t yell, we didn’t scream. We only embraced silently, crying, and then we went home to tell the girls.

“Our Josh. Our Joshy. How did I feel? As if someone had ripped my heart out of my body and tossed it between that truck and his friends’ little car, crushed along with my son’s body. I didn’t leave the house for weeks. I stopped going to the university and the institute. When I got out of bed, I’d sit on the living room chair, watching the desert mountains and saying nothing, for days on end. That’s when I stopped laying tefillin—secretly, of course. I didn’t make any big statements. After all, according to some people, I’m an Orthodox rabbi. I dropped the book I’d been writing. I didn’t want to do anything. Didn’t want to live. I imagined Josh’s final moments, felt his pain, the pain of organs smashing and bones shattering, the realization that this was it, it was all over.

“After two months, I knew there was no point to any of this. And so, one morning I got up, washed my face, shaved my beard, and cut my hair. I returned to the institute and the university and the writing desk. The next book I published only came out in 1993. It took me six years to finish it, and it’s really a little pathetic—Religion, History, and Revelation. An adaptation of six lectures. It didn’t sell well. No matter. A few years passed, the pain diminished. At the institute, we started the Yehoshua Binyamin Jesselson Young Scholars Program. Every year I watch them, the young, ambitious researchers, taking their first steps in the world of Jewish philosophy. They walk into the program’s opening ceremony all aflutter.

“The greatest change I’ve made personally was taking on a new name—Yavin, a Hebrew acronym: Yehoshua Binyamin Jesselson. To commemorate the name of my dead son on my tongue and the tongues of everyone around me. From that day on I’ve been Mordechai Yavin-Jesselson, a cumbersome name for anyone who isn’t aware of my son’s existence, but one that offers some solace to his aging father.”

“I don’t write of any of this in my memoir. I mostly deal with the institute, whose origins began in the late 1960s, when I got the PhD from Harvard, a job as an adjunct professor at Hebrew Seminary, and a position as a congregational rabbi.

“When we decided, after the Six-Day War, that it was time to tie our fates to the State of Israel, I reached out to Professor Hizkiyahu Havatzelet, who was a department chair at Tel Aviv and knew me from one of his visits to Hebrew Seminary. I was taking private Hebrew lessons. Of course, I knew the language from yeshiva and from shul, but I wanted to make it my own. That’s how I started reading Hebrew literature—Agnon, Bialik. I think someone sent me from Israel a copy of Oz’s Where the Jackals Howl. I told Havatzelet about our plans for aliyah and inquired, delicately, whether there was an opening at Tel Aviv. Speaking with an enthusiasm that wasn’t typical of a man who mostly deals in talmudic philology, to my surprise and fortune, he said that there was.

“We arrived in Israel just before the chagim and unpacked in our little apartment in Kiryat Shmuel. It took a year before we moved to this spacious Talpiot home. The school year started at Tel Aviv a week after Sukkot. I taught a seminar about theological responses to the Holocaust—the topic of my dissertation—and Introduction to Jewish Theology, which later became Introduction to Jewish Philosophy, and a few other courses that have slipped my mind.

“Our first years weren’t easy. I remember, a year after we arrived, a launch event for my book on theology and the Holocaust at the Vanderbilt Institute in Jerusalem. All of my friends and admirers showed up. Paulina sat in the front row. Professor Steif was invited to say a few words about the book. Steif, who had made a name for himself by writing about Gordon and Zionism and Ahad Ha’am and so on and so forth, began with a long, detailed description of his own research on theology and Zionism, before moving on to pan my book. He spent long minutes shooting arrows at me, arguing that my book was typical of diasporic American thought, lacking any perception of what true research was about, and possessing no understanding of the deep currents of Jewish philosophy nor tools for appreciating the great Zionist-Jewish revolution. Oh, well.

“A week later, I was at the university library here in Jerusalem, looking for a book, when all of a sudden I saw Professor Steif at one of the tables. I walked over. ‘Hello, Professor Steif, we met just last week at the event at the Vanderbilt Institute.’ Steif looked up from his book, smiled blankly, and said, ‘I apologize, but with whom am I speaking?’

“After a year at the university, I felt that teaching no longer satisfied me. The mysteries of academic bureaucracy held no appeal. I wanted a lively exchange with students; a bubbling beit midrash like I had at Brownswood or the Modern Orthodox yeshiva or even, to an extent, at Harvard. Here, I was a department chair, standing in stifling lecture halls, facing young students who were jotting down notes, taking tests, writing papers. From time to time they asked a question or two. Something—passion? Eros?—was missing. And I, entrepreneur that I was, did not rest on my academic laurels. I gathered some good people, young and old, whom I’d met in Jerusalem or at the university or who immigrated with us from America—my former congregants, Hebrew Seminary students—and one day, in 1974, I founded the institute, which at first was nothing more than a study group at a Talpiot synagogue. It took time before we built this beautiful campus. But I knew how important it was to establish a place, to name it, and to make it our home. Along with some friends, we picked a name: The Institute for Israeli Judaism.

“People at the university raised their brows. These days, when I think back to the way my colleagues behaved at the time, I despise almost all of them. I can see that none of them, yes, none of them, did anything beyond teaching and research. These library mice, people who never gave any serious thoughts to education, leadership, or public needs, they let their entire beings shrink down to their specialties: medieval philosophy, modern thought, Kabbalah, Talmud. As charismatic as the sole of a shoe, they’d walk into the classroom, give their lectures, and return to their dim offices. I wanted something else.

“No, they didn’t like what I was doing. Some of them—never mind who—tried to block my promotion with all sorts of bizarre accusations. They said my classes reminded them of American sermons, that I made a mockery of teaching, that my books weren’t academic. Scum, scum, envious and narrow-minded. Of course! The institute was at the center of my attention and was where I invested most of my time and energy. The university was a day job, and I gradually began to teach mostly my own doctrine. Rather than waste time on philosophers, theologians, and rabbis with whom I intensely disagreed or who expressed similar ideas to mine, I taught myself, my own world, what I thought and mused and created and later wrote in my books. In 2001, I retired from the university, sparing me the long drives to Tel Aviv, the morose faculty meetings with colleagues I didn’t appreciate and who didn’t appreciate me. No one shed a tear.

“Since then, I’ve been here all day, writing, recollecting everything that’s been forgotten, opening the books of memory. Years, long years absorbed into the walls of the institute, years and secrets, some uncovered, others I might reveal, and a few I’ll be taking with me to the grave—Har HaMenuchot Cemetery, parcel 39, plot 7, right next to Paulina.

“What have I got to lose? Death can come calling any morning. Every evening I take a stiff drink to celebrate my victory over it. I’ll finish the book. Writing it, which has been especially challenging, makes everything I’ve buried in my heart, like notes in the Western Wall, rise to the surface. I’ll lay out the story of this place before you, its finest years, and also, the years when it nearly slipped between my fingers, how I had to fight for dear life to keep it until the threat was neutralized and peace was restored.”

Suggested Reading

Od Tireh, Od Tireh . . .

The Hebrew Teacher is the first of Maya Arad’s acclaimed fictions to appear in English. It’s also surprisingly timely.

The Ruined House (An Excerpt)

In 2014 Ruby Namdar won the prestigious Sapir Prize for his novel Ha-bayit asher necherav, the first time in the award’s history that it went to a writer not living in Israel. On November 7, 2017, Harper released it under the title The Ruined House: A Novel, in an English translation by Hillel Halkin. The Jewish Review of Books is pleased to present this excerpt from the novel’s opening.

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

Tradition and Invention

If Jews were included in early 20th-century discussions of political communities, it was generally concerning their right to preserve their language and culture, along with other minorities, at a time when empires were being dismantled.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In