Ghosts of Hooligans Past

“Going to Bristol City next week, Mark?” Spunky asked casually. I told him I couldn’t.

“Why’s that? Going on holiday?”

“Won’t be around for a while.”

“Ah. Going inside?”

He’d given me my out. I nodded.

“What for?”

“Manslaughter.”

“Oh. Sorry to hear that mate. I’ll keep all the programs for you!”

Though from a bourgeois, Anglo-Jewish literary background (my father is a novelist who is also considered the doyen of soccer writers), I had been drawn to the working-class world of football hooliganism in my early teens. This was after my parents transferred me from a privileged English school to a working-class one. My mother somehow perceived nonexistent parallels between newfangled state “comprehensive” schools in 1970s England and the German gymnasia she had grown up with.

I was mercilessly bullied at the new school. My nose was broken, and I was repeatedly headbutted and had a flick-knife held to my throat. When a classmate told me to “stop being Jewish with the ball,” I spat in his face. A teacher broke it up. “He would have killed you,” another student told me. But he hadn’t done. I was fighting back now and decided to up the ante. Football hooliganism was a big part of British working-class culture. I first attached myself to the local Queens Park Rangers Loft Boys, battling rival fans on the terraces. It was another level of danger—riskier, more violent, larger scale. Next to football thugs, school bullies were paltry fare. But I was becoming addicted to the terrace camaraderie that compensated for lack of friendships at school and the adrenaline rush that came with violent clashes.

I began following my chosen club, Manchester United, all over the country with the London-based Cockney Reds. Danger was everywhere, from supporters of the clubs we traveled to play to those of London clubs who waited at stations to ambush us.

Once, when United played Tottenham Hotspur, a club known for its Jewish following, a huge skinhead positioned himself next to Spurs fans and began chanting his way through the antisemitic repertoire reserved for that club. But then he went further, adding an old Mosleyite slogan from the 1930s: “The Yids, the Yids, we’ve got to get rid of the Yids.” I waited till the game was over, followed him, and fly-kicked him in the spine with as much force as I could manage. He winced, half-turned, then walked on. Not long after, I went up to Oxford for a classics degree, not “inside” for manslaughter, as I had told Spunky. But I had known the addictive rush of violence.

Later, after Oxford, I began following Millwall, the club with the most notorious supporters in the country. Millwall’s Bushwhackers firm were mostly of Irish, West Indian, and Turkish descent. They were proud of having stopped the neo-Nazi National Front from marching in Bermondsey and enjoyed fighting the notoriously racist, antisemitic Chelsea thugs. A friend from a staunch Millwall family in Stepney, close to the docks where the club had originated, took pleasure in showing me the houses close to his home where Jews had once lived and the synagogues they prayed in. His mother had been a Shabbes goy. A close Jewish friend of his, Podge, was a member of Millwall’s Treatment firm, famous for wearing hospital surgical masks to matches. Yiddish words and expressions peppered the London argot they spoke.

My mum was born in Amsterdam, and kept her Dutch passport till the day she died, so Amsterdam is a city to which I’ve always felt connected. Though, as with other places in Europe where Jews were extirpated, you still feel the breath of their ghosts on your face. The city is also home to Ajax, a great European soccer club with a famously philosemitic fan base who call themselves “Super Jews.” When they take the pitch, supporters of their rivals often hiss to imitate the sound of the gas chambers.

A couple of months ago, Ajax played Maccabi Tel Aviv in a Europa League match. Earlier in the year, Maccabi had played in Athens, and some of their supporters beat up a man carrying a Palestinian flag in Syntagma Square. Before the game in Amsterdam, Maccabi fans tore down a Palestinian flag and chanted anti-Arab songs. After the game, local Muslim gangs stalked, attacked, and terrorized Maccabi supporters and anyone else on the streets they thought was Jewish.

Of course, the widely reported news of this violence took me back to my own hooligan days, but the attacks on Maccabi Tel Aviv supporters had little to do with the game. And, needless to say, the attackers were not “Super Jew” supporters of Ajax. In fact, it turned out that the attacks had been planned weeks beforehand (though no doubt the Maccabi fans’ pregame hooliganism added fuel to the fire). The Amsterdam police seem to have been aware of the plans, though they proved spectacularly unprepared—to put it charitably—to prevent the attacks or even respond to them. Israelis sheltered in hotels, and El Al sent special flights to Amsterdam to ferry them safely back to Israel. Amsterdam’s Mayor Femke Halsema called the attacks a “pogrom”—and then took it back.

I’m writing this a week before seeing Millwall play at Portsmouth and Oxford United. In the past these fixtures would have been considered “tasty,” which, of course, is to say violent. All three clubs have notorious hooligan followings.

Oxford’s following is from the rough Cowley projects that housed autoworkers. It’s often said that no Oxford student left the university without being attacked by these townies. When an Oxford undergraduate, I would tag along with Millwall supporters when they played Oxford United in the hope of exacting a bit of revenge against them, but today I rarely feel that burn in the stomach anymore. And I have respect for Portsmouth fans, who are what football fraternities term “proper.” I’ve arranged a drink before the game with a Portsmouth-supporting mate in one of their pubs. At Oxford I’ll enjoy a Shabbat dinner with academic Jewish friends before watching the game in the home-team end on the following day—peaceably, I’m sure.

The formation of the Football Lads Alliance, founded in 2017 in the wake of appalling Islamist terrorist atrocities in the UK, put many of these old enmities to bed. Former football foes marched together against what they perceived to be a common enemy. For most of them Israel is an ally, a bulwark against Islamist terror. Roy Larner, “the Lion of London Bridge,” a Millwall supporter who nearly died taking on three knife-wielding jihadis, saving countless lives in the process, is a hero across the UK.

Perhaps what happened both before and after the game in Amsterdam was a kind of European football violence after all, but in a new, and even more ominous, form.

Suggested Reading

Heart Work

As a successful young novelist, my father had literary friends who now included Angus Wilson, Frederic Raphael, John Wain, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. All came to tea in my nursery. Stanley Moss, my godfather, went on to make a fortune from art dealing.

If God Wills It, a Broom Can Shoot

“Are you really intending to raise our kids,” my wife Tali asked me one Saturday afternoon after our Shabbes lunch, “in a world that doesn’t have Harry Potter in Yiddish?”

A Perfect Spy?

Was the original James Bond a Jew from Odessa?

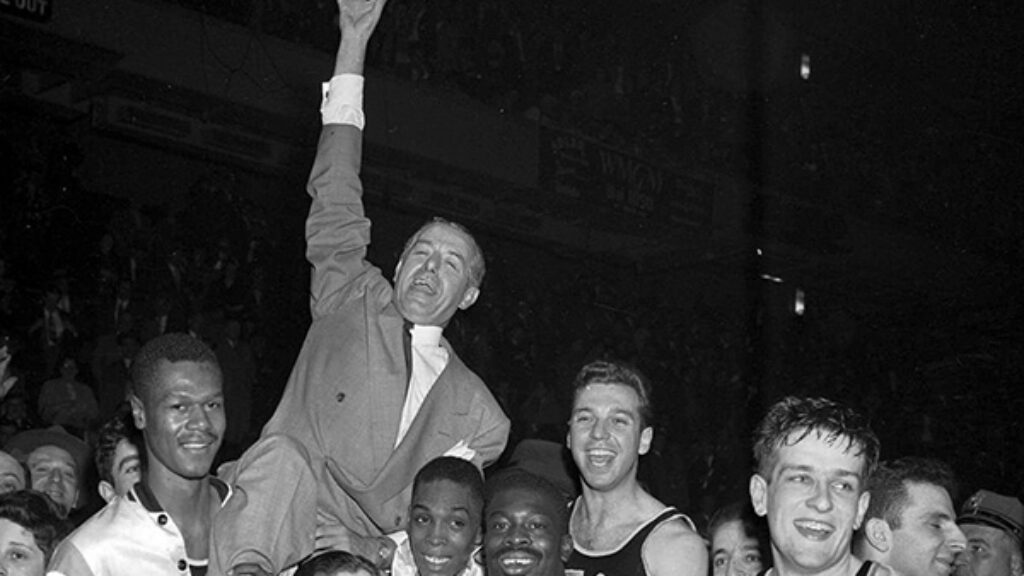

The Fix Was In

The 1951 basketball game that pitted CCNY, which fielded blacks and Jews, against the all-white University of Kentucky seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In