Heart Work

Brian Glanville, an emerging London novelist, first met Stanley Moss, a budding New York poet, in Rome in the early 1950s. Dad had not gone to university, and his friendships made in Italy during that time were like those others make at college, influential and enduring. When I was born, he chose to make Stanley my godfather.

Stanley’s first collection, The Wrong Angel, wasn’t published until 1966, though it contains poems dating back to 1949. By then my father had already published nine novels, some relating to his time in Italy, others to Jewish family life. One, The Bankrupts, caused a furor, leading to a highly publicized libel suit against the actor David Kossoff, who had accused him of writing an antisemitic handbook. The Bankrupts is, in fact, an unremittingly negative portrait of a materialistic north London Jewish family that has forsaken religion and culture, but my father was no self-hating Jew. He was more of a latter-day Moses striking down idolaters. He won the action.

His relationship to Judaism is, however, complex. My grandfather, Selick Goldberg, became James Arthur Glanville and sent him to Charterhouse, an English public school where antisemites abounded. Antisemitism, perhaps unsurprisingly, defined my father’s sense of his Jewishness, a battle to be constantly fought, sometimes in the street, more often in discussions around the dinner table. My parents held no Seders, nor did they observe High Holy Days. I had no bris, no bar mitzvah either. Sigmund Freud, not Hakodesh Baruch Hu, was their god, and he had decreed that circumcision would lead to a castration complex.

As a successful young novelist, my father had literary friends who now included Angus Wilson, Frederic Raphael, John Wain, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. All came to tea in my nursery. Stanley, my godfather, went on to make a fortune from art dealing. Dad made his name (and most of his money) as a sportswriter. He never stopped writing novels, but football (soccer) became his life. Instead of literati, athletes came to tea. I loved the game too, but I missed novelist dad and his writer friends, Stanley in particular.

To my five-year-old self, Stanley, a six-feet-four-inch colossus, was “Big Man.” His first godfatherly gift to me was a set of skis, which carried me down Austrian slopes while my mother confronted impenitent former Nazis in shops. After that, I rarely saw him. He lived thousands of miles away on the other side of the pond. Then, in 1989, I won a scholarship to study singing in New York and went to stay with him in Riverdale. At the top of his house, opposite my bedroom, was a storeroom filled with books printed by his publishing house, Sheep Meadow Press. One, a red softback galleys edition of Collected Prose by Paul Celan, introduced me to the writer whose sense of Jewishness gave me the key to the identity I had been seeking. He wrote in “Benedicta”:

You have drunk

what came to me from my fathers

and from beyond my fathers:

–, Pneuma

Celan’s Jewishness was “pneuma” (breath), something intangible that could not be codified; it was poetry, humor, song. That I could relate to.

Stanley’s work had a Celanian flavor. In “Diary of a Satyr,” a rare prose piece, he writes that he “had entered . . . a synagogue, only once, to tell my grandmother on Yom Kippur that my mother was waiting outside in the car.” Yet, in “The Poem of Self,” he writes:

Looking back, God is a verb, adjective,

article, contraction, infinitive, any part of speech,

any language, since every living thing speaks God.

God is a verb—

The God of my godfather is in everything and everywhere, a unifying force.

Twenty years ago, Stanley underwent heart surgery and wrote in “Heart Work”:

No moon is as precisely round as the surgeon’s light

I see in the center of my heart.

Dangling in a lake of blood, a stainless steel hook,

unbaited, is fishing in my heart for clots

A few years later, my father, too, had a major heart attack, outside a soccer stadium after a match. Stanley was on the phone constantly, proffering veteran’s advice, including to my mother who, sadly, misinterpreted his good intentions. As a result, my father became broyges with one of his oldest, most important friends.

When Stanley came to London, Dad no longer saw him. He and I would meet up in the Trafalgar Square hotel he chose for its proximity to the National Gallery and West End theaters. He always began by asking fondly after Dad, confused as to why he had been cast out. Gathering scattered pages covered in inky pictograms, his latest poems, he would beckon me to sit down and listen. It was no hardship. Stanley, who turns ninety-six in June, is at his most prolific and inspired, with new poems cropping up in journals everywhere. His latest collection, Not Yet, to be published later this year, will contain around fifty poems written between August 2020 and April 2021.

“The Chinese melted my heart of U.S. Steel into a wildflower,” he tells us in “Preface,” the book’s first poem. At a time when most talk of China addresses the country’s global threat, it is refreshing to read a book influenced by and extolling Chinese people and culture. Elsewhere in the new book, Stanley deplores the Capitol rioters, commiserates with a Kurdish poet imprisoned by Erdoğan, and contemplates the effects of COVID-19:

Everything since the Virus seems inconsequential:

what is, was, or might once have been

beloved or despised, the enchanting.

He is a nonagenarian who has not been outlived by his times, taking his cue from the ninety-year-old Sophocles, who saved his best for last with Oedipus at Colonus.

Following his heart attack, Stanley told me, “I can get my emotions into words.” The candor and directness of his poems have undoubtedly increased with age, as written in “A Rum Cocktail”:

I tighten both my fists. I won’t let go

I’ll write a leaflet of last words.

I cough and spit blood,

I take my finger and make a flower of blood and spit.

In a poem called “Murder,” he tells us:

The ship of life is sinking, poetry is a lifeboat,

wintry death murders, poets give us an overcoat.

It is one I choose to wear now more than ever.

Suggested Reading

The Kibbutz, Post-Utopia

One hundred years ago, Yosef Bussel, Yosef Baratz, eight other young men, and two young women arrived in Umm Juni on the southern shore of Lake Tiberias. There they established a kommuna, a small agricultural settlement that was to become the first kibbutz. A new Hebrew book celebrates the centennial history of this great experiment.

Jewish Destiny in a Cheek Swab

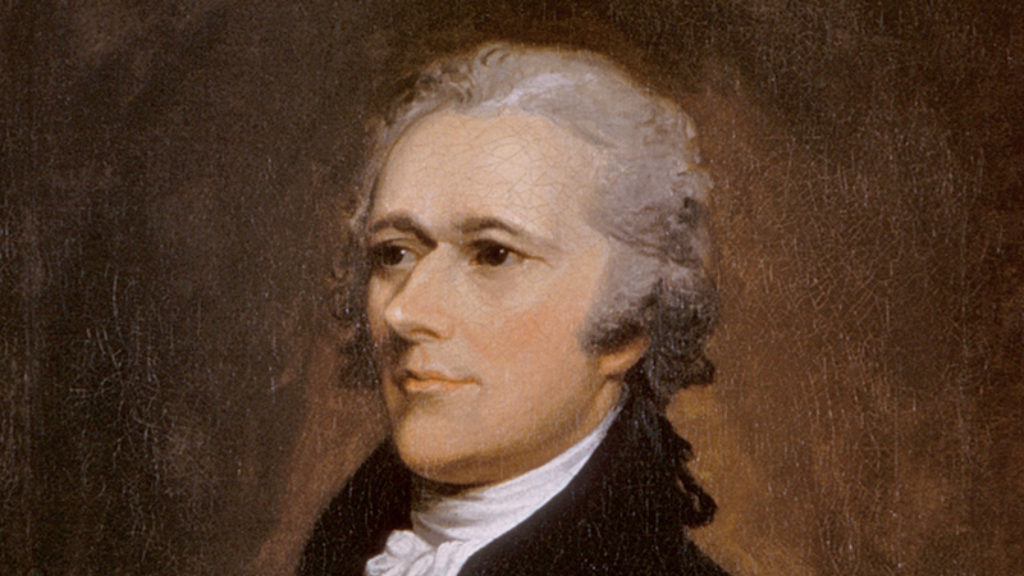

Possible Jewish ancestry has fascinated both Jews and non-Jews when it comes to American historical figures, reaching as far back as Alexander Hamilton.

I’m Still Here

Tuvia Reubner has said he has no homeland except perhaps his poetry. A new book expands that homeland's borders.

The Anti-Jewish Problem

In the competition that took place between Judaism and nascent Christianity, only one could be correct. Thus, anti-Judaism became central to the Western tradition.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In