A Perfect Spy?

“A right chancer.” That’s what my father, z”l, an East London street kid to his very core, would have called Sidney Reilly, and not without a tinge of admiration. It takes one to know one, I reckon, but the portrait that emerges from Benny Morris’s Sidney Reilly: Master Spy is less a rendering of a spy than it is of an opportunist, a risk-taker, and a smooth-talking charm merchant (his bewildering web of love affairs and marriages warrants a book in their own right) with an instinct for being in the right place at the right time. Until he wasn’t. This is a man whom nobody ever really knew. And Reilly, it seems, wanted it that way.

First, there is the puzzle of his origins and early life. Born Sigmund Rosenblum, of uncertain paternity, sometime in the early 1870s, he grew up in Odessa, one of the great Jewish cities of the nineteenth-century world and one of the single most cosmopolitan places in the entire Russian empire. Other notable native sons include Isaac Babel, Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky, and Leon Trotsky (although Trotsky was what Nova Scotians call a “come from away,” from Kherson). Suspected of involvement in radical student politics, young Rosenblum was arrested by the Okhrana, the tsarist secret police, in 1893 and held for a week in solitary confinement, during which time his mother died. Living in a viciously antisemitic milieu, with no real family and a police target on his back, Sigmund Rosenblum made the same decision as hundreds of thousands of other Russian Jews—he left.

Afterward, Rosenblum appears to have bounced around the world, trying his hand at various business ventures—from fine art, to petroleum, to pharmaceuticals—with varying degrees of success. He was probably also freelancing for the Okhrana (likely the price of his release from solitary), keeping an eye on Russian émigré revolutionary groups.

He also began working for the Special Branch of Scotland Yard, which took an equally dim view of potential subversive elements. It is probably at this point that Rosenblum was reborn as Sidney Reilly, receiving a British passport in that name in 1899. He probably also began working for an early iteration of MI6, Britain’s foreign intelligence agency, which was primarily concerned with countering the threat from an increasingly militarized Germany. Whether he was an asset/agent or an actual officer of the Crown remains unclear. Before the Second World War, most Western intelligence agencies relied heavily on freelancers and gentleman amateurs, although it is unlikely that anybody in the Foreign Office ever mistook this Odessa Jew for a gentleman.

Gentleman or not, Reilly soon found himself at the center of the twentieth century’s first arms race. In the years before the First World War, a few visionaries—among them Winston Churchill and British admiral Jackie Fisher—understood that the future of warfare lay in technological supremacy: in this case, control over the new technology of oil production. The Royal Navy, whose capacity to rule the waves was being challenged by German dreadnoughts, was determined to convert its coal-burning ships to oil, thereby increasing their range and obviating reliance on far-flung coaling stations.

In 1901, William Knox D’Arcy, an Australian financier, persuaded the shah of Iran to grant him a sixty-year oil drilling concession that covered most of Persia. In need of financing to start drilling, D’Arcy turned first to the French branch of the Rothschilds. The British government got wind of this and dispatched its best man. By his own account, Reilly disguised himself as a priest, talked his way aboard the yacht where the critical meeting was taking place, and somehow persuaded D’Arcy to make his ask in Britain instead. Other versions of the story have Reilly (still disguised as a priest) persuading D’Arcy not to sign on with John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and even slipping the Rothschilds a fake report that Persian oil reserves were vastly overreported.

Whatever the truth of the matter, D’Arcy ended up seeking out British backers and set up the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (in which the admiralty was a major shareholder). In the fullness of time, Anglo-Persian became the British Petroleum Company, now BP, one of the world’s most profitable corporations. It’s a gripping story, but the most maddening thing about the first part of this book is its reliance on modals like “would have,” “could have,” “might have,” and “appears to” and adverbs like “possibly” and “maybe.” This must have troubled Benny Morris, a distinguished historian, but he had little choice. In one illustrative passage, Morris writes:

Special Branch may have felt in a bind, given that Reilly was one of theirs. Lastly, Margaret appears to have taken to drink and was perpetually on edge. For Reilly, going abroad may have appeared a good solution. One can assume that his departure was at least in part at the behest of British intelligence and Melville, who may have “loaned” him to the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Department with a specific purpose in mind.

As Morris himself says, in what could be the coda to Reilly’s life, “It sounds like a tall tale, but who knows?”

What we do know is that in 1918, Reilly, now a full-time employee of MI6 and completely metamorphosed into a British patriot and a commissioned officer in the Royal Flying Corps (though it is unclear whether he ever received any training as an airman), was sent to Russia. The Allies feared that the new Soviet state might throw in its lot with Germany after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and were determined to stop that from happening, even if that involved the overthrow of the Bolshevik government. Reilly, no lover of Russia’s ancien régime, but perhaps sensing opportunity, became a key figure in these machinations, which came to be known as the Ambassador’s Plot.

As a Russian speaker, Reilly traveled between Moscow, Petrograd (soon to be renamed Leningrad), and Arkhangelsk, recruiting a mishmash of anti-Bolshevik operatives—Socialist Revolutionaries sidelined by the victorious Bolsheviks, disgruntled tsarist officers, and aristocratic “former people”—with promises that an Allied-funded and-supported coup d’état was imminent.

But Reilly’s instincts, and his tradecraft, appear to have been compromised, as one contemporary put it, by his belief that “he was destined to bring Russia out of the slough and chaos of Communism. He believed that he would do for Russia what Napoleon did for France.” He failed to realize that the Cheka (subsequently the OGPU, the NKVD, the KGB, and now the FSB) had infiltrated the operation from the beginning. This, along with a nearly successful attempt to assassinate Vladimir Lenin, led to the so-called Red Terror of August and September 1918. Within two weeks, the Cheka had rounded up and executed nine thousand conspirators, including at least twelve of Reilly’s agents. Reilly escaped, and the attempt to “strangle Bolshevism in its cradle,” as Churchill later characterized it, soon came to an ignominious end.

Reilly wasn’t finished, though. By the end of 1918, he was back in Russia, this time in his hometown of Odessa, reporting back to MI6 on the progress of the Civil War in Southern Russia where three armies—White, Red, and Ukrainian nationalists under Symon Petliura—were engaged in an existential struggle. Reilly was unabashedly partisan, praising White commander Anton Denikin’s “absolute honesty . . . political moderation, immense popularity and . . . loyalty to the Allied cause” and dismissing Petliura as “ephemeral.” What he failed to mention was that the region’s Jews were helplessly caught in the middle of this war. Pogroms across Ukraine and the Donbass dwarfed those of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, resulting in an estimated fifty thousand casualties. Of these, more than 90 percent were carried out by Ukrainian nationalists or Denikin’s Whites and about 8.5 percent by the Red Army.

Even with their knee-jerk Edwardian antisemitism, Reilly’s upper-class colleagues in MI6 and the Foreign Office were horrified by what they saw. “The longer and more bitter the struggle against the Soviets,” wrote Captain George Hill in June 1919, “the more sanguinary the pogroms.” But Reilly evidently cared little for the fate of his fellow Jews, downplaying their plight in his reporting, and characterizing them as a pro-German fifth column. As Morris notes:

Reilly repeatedly singled out for vilification promiscuous or (in his eyes) “ugly” Jewish women. Years later, in 1925, according to Cheka reports, when told of the possibility of the outbreak of massive anti-Jewish pogroms should the Bolshevik regime go under, Reilly seemed chiefly interested in the deflection of blame away from his counterrevolutionary colleagues rather than in their prevention.

Herein lies the central theme of Reilly’s life. From his name to his passport to his officer’s commission, Reilly seemed to go to great lengths to conceal, even repudiate, his Jewish identity. This is, of course, not an uncommon story. My own great-grandfather, arriving from Minsk and faced with the ambient antisemitism of early-twentieth-century small-town Ontario, explained his accent and his unsettling resemblance to Vladimir Lenin by claiming to be a Quaker.

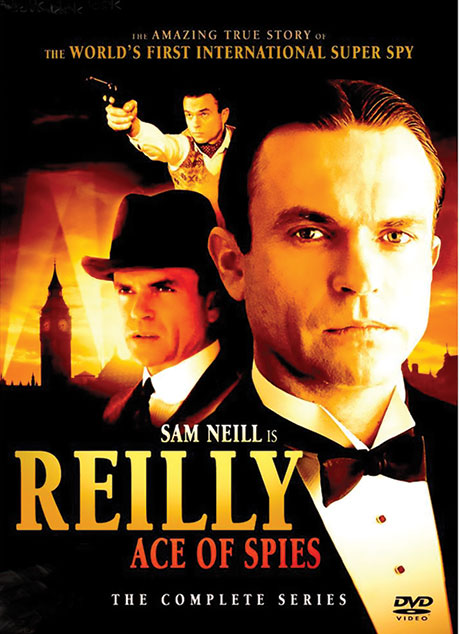

Cover for the British television series Reilly, Ace of Spies with Sam Neill as Sidney Reilly, 1980s.

Jewish history is full of shape-shifters and tricksters, and certainly Reilly seems to be one of them. In the story of his life, there is virtually nothing overtly Jewish. That, as above, seems to be the way he wanted it, and certainly, history has been cooperative in the deracination of Sidney Reilly. In the early 1980s, the British television network ITV produced a highly watchable miniseries called Reilly, Ace of Spies. The swarthy, heavy-lidded Reilly is played by young and impossibly handsome New Zealander Sam Neill. Even while eluding savage tribesmen and corrupt and slovenly tsarist officials in the Caucasus, this Reilly is impeccably turned out in a beautifully tailored alpaca suit and a rakishly tilted Panama hat. Cool as a British cucumber, he faces down hirsute, garlicky Bolsheviks in revolutionary Moscow and Petrograd. But for all the swashbuckling narishkeit, there is a poignancy to this Reilly that feels somehow real. “I was a Jew, a Jewish bastard,” he says in a rare moment of introspection. “My childhood became like a dream, something I had imagined.”

Sidney Reilly has been posited as the model for Ian Fleming’s James Bond. But then again, so have a lot of people, including Fleming’s own brother Peter, the Second World War triple agent Duško Popov, and the Canadian financier William Stephenson. Somehow, I don’t see it. If there is any link between Bond and Reilly, it is in the movies, not the novels. Sean Connery and Daniel Craig, with their uncertain, possibly working-class origins and their whiff of old-time thuggery, are not so far from Reilly/Rosenblum.

By the early 1920s, Reilly was out of MI6. His cover was blown, his activities during the Civil War had resulted in an in absentia death sentence courtesy of the Cheka, and, besides, Britain and the USSR had reached an uneasy detente. His day was done, and he was bereft at his abandonment. Nevertheless, the overthrow of the Bolshevik regime remained his personal obsession. To this end (and perhaps sensing a business opportunity), he teamed up with an old Socialist Revolutionary comrade, morphine addict, and anti-Bolshevik rabble-rouser from his Moscow days named Boris Savinkov. To Reilly, “he was and is and always will be the only man outside of Russia worth talking to and worth supporting.” For all of Savinkov’s supposed genius, he was the target of a massive OGPU sting operation, a fabricated anti-Soviet network known as the Trust. Persuaded to return and lead the coup, Savinkov was arrested, tried, and executed, probably thrown to his death from a fourth-floor window in the Lubyanka. Reilly, however, believed firmly in both the reality and the potentiality of the Trust. OGPU agents lured Reilly to Russia, and after a long imprisonment and interrogation (which included a Dostoyevskian fake execution), Sidney Reilly was shot to death by the OGPU during an outing in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park in November 1925.

I came to this book wanting to like Reilly; I finished it with a deep sense of sadness. Why did Reilly shed his Jewishness so readily? Even his final Soviet interrogator noted that he was “extremely bothered by being a Jew and made every attempt to conceal his origin.” I reluctantly concluded that the most Jewish thing about him was probably his residual Odessa street smarts, his evident gift with people, and his fascinating ability to move back and forth between languages and cultures.

Reilly’s life was that of a man of mystery, but it was no James Bond romp through the glamorous world of international espionage. Despite all the accolades over time—“Master Spy,” “Ace of Spies”—Reilly’s vanity always seemed to get the better of him. His elaborate operations never quite came to fruition, he betrayed agents and informants, and he ended up walking into a trap that elementary tradecraft would have certainly helped him avoid. With his small, still historian’s voice, Benny Morris interrogates the mythic career of Sidney Reilly who, to the bitter, tragic end, “remained principally wedded to Reilly.”

Suggested Reading

Muddling Through

In his new book about an Upper West Side Jewish family, Joshua Henkin proves himself as a skillful writer, alternately witty and moving.

Diaspora Divided

In his new book, Peter Beinart leads a full-court press against the current state of Zionism. Expanding on his now (in)famous article, "The Failure of the American Jewish Establishment," Beinart sets out to convince young liberal Jews to join the battle for Israel's soul. Noble but misguided, his crusade is sure to backfire.

You Shall Appoint for Yourself Judges

Was the once-head of Israel's Supreme Court a robust defender of human rights or a runaway judge who imposed his political preferences on a nation? Tom Ginsburg explores the legacy of Aharon Barak.

The Fierce Lust for Contemplation

How did traditional yeshivas become fertile ground for radical literature?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In