Out-of-Body Experiences: Recent Israeli Science Fiction and Fantasy

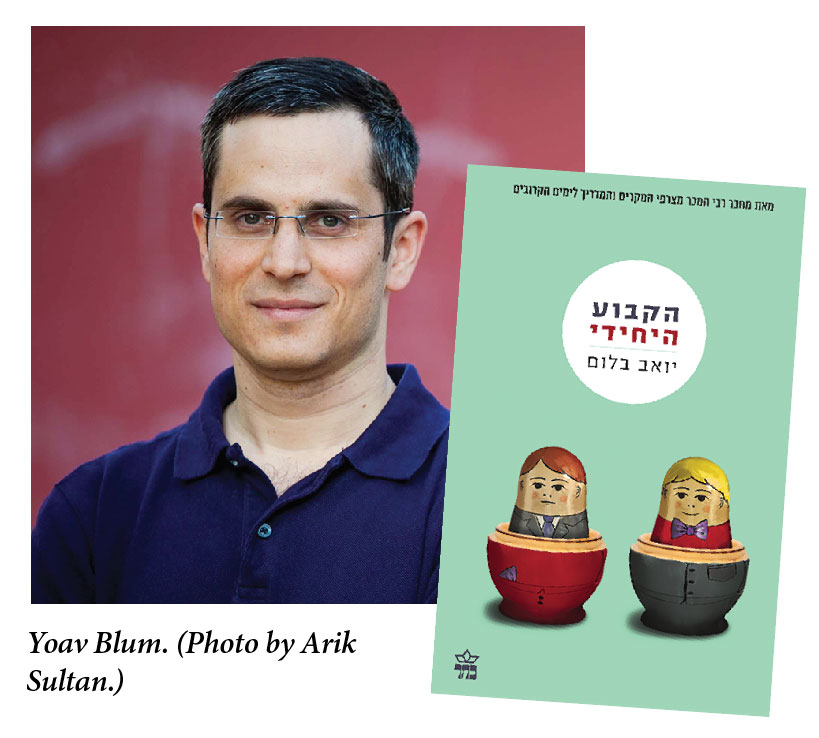

In 2017, the Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy awarded its Geffen Award for best novel to Yoav Blum’s Ha-kavua ha-yechidi (The Unswitchable). The novel, Blum’s third (his first will soon appear in English translation as The Coincidence Makers), imagines the invention and proliferation of bracelets that allow the wearer to “switch”: to swap consciousnesses with other bracelet wearers by dialing them up as if on a phone. The technology finds all sorts of applications, from the practical to the illicit. Telecommuting for work often becomes a jump into someone else’s body, while some couples periodically have sex from the other partner’s perspective. There are even fellowships of people who agree to set their bracelets on a randomized mode for months at a time, during which their minds bounce around from body to body without knowing who, what, or where they will be from day to day.

The novel, then, reflects uncertainty about identity in our new virtual world. The protagonist is a private eye named Dan Arbel, who is the sole “unswitchable,” the only person for whom the bracelets don’t work. In a world in which you’re never sure who you’re really speaking to, he is, for better and for worse, always himself. As he reflects:

What does it really mean to be grounded in yourself in such a world? It means going around in a little universe of yourself while everyone else speeds by in front of you. . . . You move from place to place, imprisoned in the same old weakening body . . . without even the privilege of a nice morning run in the body of a 20-year-old, the ability to leave it all suddenly and jump for a half hour to the view from the top of the Empire State Building or a quick dive into the Caribbean or the sunset over the African savanna, then back for dinner, toothbrush, and sleep.

Arbel’s condition is a bit like what we might experience being the only person in the world without internet access. Though we may not need the novel’s reminders that the rush of social media can corrode the self, Arbel’s outsider standpoint makes him sensitive to more enduring technologies for escaping and discovering our true identities: love and religion. Not that this potboiler focuses much on such lofty matters—Blum is having too good a time spinning out a fun thriller that combines the sci-fi, detective, and action genres.

The novel starts off with a literal bang as the wealthy Caitlin Lamont enters Arbel’s office and confides that, despite her body, she is really his old flame Tamar—just before getting shot by a sniper across the street. Blum wears his genre markers proudly, referring by name to Arthur Conan Doyle and sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick, even writing one section of the novel in the form of a Hollywood screenplay with notes such as “Outside, an owl makes the noise owls make in movies at night.” Yet even while stretching credulity like taffy, Blum signals his awareness that, long before his book, the rabbis similarly presented the mind-body problem as a whodunit in the parable of the lame man and the blind man (that is, the soul and the body) teaming up to commit a crime with a mutually reinforcing alibi intended to outwit the divine judge.

The novel starts off with a literal bang as the wealthy Caitlin Lamont enters Arbel’s office and confides that, despite her body, she is really his old flame Tamar—just before getting shot by a sniper across the street. Blum wears his genre markers proudly, referring by name to Arthur Conan Doyle and sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick, even writing one section of the novel in the form of a Hollywood screenplay with notes such as “Outside, an owl makes the noise owls make in movies at night.” Yet even while stretching credulity like taffy, Blum signals his awareness that, long before his book, the rabbis similarly presented the mind-body problem as a whodunit in the parable of the lame man and the blind man (that is, the soul and the body) teaming up to commit a crime with a mutually reinforcing alibi intended to outwit the divine judge.

As it happens, another book on the Geffen Award shortlist, Ofir Touché Gafla’s Ha-orchim (The Guests), also features a private-eye protagonist in a world in which people switch bodies. This coincidence is surely the reason why Gafla includes a late subplot, unconnected to the rest of the book, about an author who seeks revenge after his novel is preempted by another writer who coincidentally treats the same science-fiction theme a few months before his book is published.

Yet Ha-orchim portrays body-switching not as a slick technological innovation but as a universal trauma. The novel opens five years after what has come to be called “The Metamorphosis,” an event in which nearly all adults on the planet wake up to find themselves transformed in their beds into the physical form of the person they hate most. Holocaust survivors wake up looking like their Nazi tormentors, countless people look in the mirror and see their ex-spouses, racists are turned into composite stereotypes of their targets, and long-hidden grudges take on corporeal reality.

Gafla, though, is less interested in the implications of this cosmic prank than he is in what he depicts as humanity’s primary response to it: an obsessive preservation of their former identities, through journals, websites, and electronic archives. Both Blum’s and Gafla’s novels are works of our moment, with characters who specify their preferred pronouns. Yet if Blum’s novel is inspired by technology’s creation of a fluid, ungrounded identity, Gafla’s focuses on our relentless chronicling of the minutiae of the self on social media. Perhaps these are two sides of the same coin, and the concern with recording and disseminating the activities of the self becomes more all-consuming as those selves grow more superficial and interchangeable. Gafla drives the point home with an Israeli protagonist named Adam Kor who finds himself in the body of a Japanese woman named Yuniko, punning on the words “core,” “unique,” and the Hebrew “mekor” (original).

Gafla, though, is less interested in the implications of this cosmic prank than he is in what he depicts as humanity’s primary response to it: an obsessive preservation of their former identities, through journals, websites, and electronic archives. Both Blum’s and Gafla’s novels are works of our moment, with characters who specify their preferred pronouns. Yet if Blum’s novel is inspired by technology’s creation of a fluid, ungrounded identity, Gafla’s focuses on our relentless chronicling of the minutiae of the self on social media. Perhaps these are two sides of the same coin, and the concern with recording and disseminating the activities of the self becomes more all-consuming as those selves grow more superficial and interchangeable. Gafla drives the point home with an Israeli protagonist named Adam Kor who finds himself in the body of a Japanese woman named Yuniko, punning on the words “core,” “unique,” and the Hebrew “mekor” (original).

Gafla’s first book, The World of the End (released in English in 2013), is one of Israel’s best novels of the fantastic (it won the Geffen Award in 2005), and he is a superb writer. Unfortunately, I think he misses the mark this time. (I say this while mindful that a critic in Ha-orchim is named Alma Mort, rather close to the Spanish phrase for “dead soul.”) There are structural problems: The slow revelation, accomplished partly through diary entries, of information that everyone in the novel is supposed to know seems unjustified, and it does not help that the protagonist seems to be the only person in Israel without a smartphone and so constantly requires his friends to deliver long expositions of current events. Gafla is at his best here when he writes of night landscapes—empty city streets, glowing windows in distant apartment buildings, dark highways with solitary hitchhikers—and of lovers who are lost and, as in a number of his earlier books, may not wish to be found. Though, on the whole, this effort disappoints, I look forward to his next book.

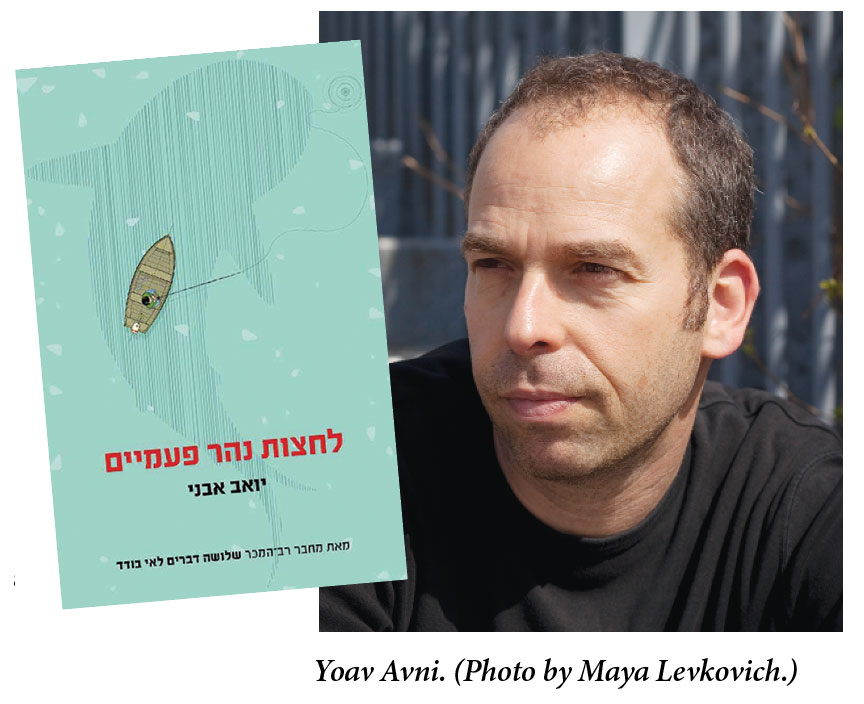

The main character in Yoav Avni’s fish-that-got-away tale Lachatsot nahar pa’amayim (Crossing a River Twice) stays in his own body the whole time. Itamar Goren, who has abandoned his job in high-tech and gone to work for yet another private investigator in Tel Aviv, might even be considered stuck in himself. Largely cut off from social interactions with anyone other than his pet goldfish, he prefers to avoid human entanglements and instead spends his free time contemplating his beloved Yarkon, the river that meanders through north Tel Aviv.

The main character in Yoav Avni’s fish-that-got-away tale Lachatsot nahar pa’amayim (Crossing a River Twice) stays in his own body the whole time. Itamar Goren, who has abandoned his job in high-tech and gone to work for yet another private investigator in Tel Aviv, might even be considered stuck in himself. Largely cut off from social interactions with anyone other than his pet goldfish, he prefers to avoid human entanglements and instead spends his free time contemplating his beloved Yarkon, the river that meanders through north Tel Aviv.

Things get complicated when Itamar’s boss goes missing and the physically imposing thug to whom he was in debt holds Itamar responsible for the owed shekels. Meanwhile, the Yarkon is invaded by foreboding deep-sea creatures whose presence drives the action of the book. While unraveling these mysteries, Itamar finds a partner in the charming Nufar, a woman who possesses the intuition and emotional intelligence he lacks, and they are joined by Ian Banks, an elderly Englishman in search of the Loch Ness monster.

Not far below the surface of this quirky tale is something closer to social allegory—closer, in fact, to Avni’s earlier novel, Herzl amar (Herzl Spoke), which won the Geffen Award in 2012. In that earlier novel Avni meditates on the nature of Israel by depicting an alternate history in which the Jewish state was founded, as Theodor Herzl briefly proposed, in Africa. Here, Itamar’s isolation and aimlessness seem to pose the question of whether the secular, high-tech face of Israel possesses the emotional and spiritual resources—the sense of magic—on which to base a thriving culture. Is there room enough in the Yarkon for sea monsters? Is being the start-up nation enough reason to start up each day?

Avni doesn’t have encouraging answers to these questions. Nufar is delightful, to be sure, but she is a Mizrahi version of the American “manic pixie dream girl” film trope, not an answer to the malaise that Avni both depicts and embodies. By the end, the Englishman Ian Banks is screaming at the IDF soldiers who have cordoned off the river and its sea monsters behind a security wall. “You Israelis!” he shouts, “You shoot at anything you don’t understand!”

It seems significant that Itamar has lost touch with his two brothers: One left to make his fortune in the United States, the other became religious. The reader ends the book sensing that Itamar, without capitalism or Judaism as compelling options, will go back to spending his days by the river, musing on what might have been.

The Yarkon is as good a site as any for pondering the relationship between Israel and the imagination. After all, a few decades ago who would have imagined that polluted canal as it is today, with its beautiful park, bike paths, and bridge of lover’s locks? Yet it’s also interesting that Avni chooses not to ride the river further back to its ancient springs by the Roman Antipatris or the biblical Aphek, let alone to any imagined Israel of the science-fiction future. Other recent Israeli sci-fi and fantasy novels, however, do draw on Near Eastern antiquity or explore the far future—and sometimes both.

Shadrach is the latest sci-fi novel by Shimon Adaf, considered by many to be the most talented and interesting of Israel’s current science-fiction and fantasy writers, though others find his novels overly self-referential and unsatisfying. Both camps will find support here. The slim novel, which is dated 2011 though it was published in 2017, cuts back and forth between an Israel of the far future, in which the main character is a teenager named Shadrach, and the early 1980s of Adaf’s childhood, in which the main character is a boy named Hanania. These names conjure the biblical book of Daniel, in which Hanania (whose Babylonian name is Shadrach) is one of Daniel’s three Jewish companions who are thrown into a furnace for refusing to worship an idol set up by the Babylonian emperor. (Adaf may have been inspired by the 1976 novel Shadrach in the Furnace by the American science-fiction writer Robert Silverberg, which takes place in a postapocalyptic future and features a short interlude in Israel.)

The novel’s future is certainly bleak—and heavily laden with political allegory. Apart from the domed city of New Sderot, Israel has been decimated by a “nano-gas” attack (possibly launched by America) that has turned its citizens into bloodthirsty zombies. In the resulting chaos, a fascistic faction known as the Guardians of Zion seizes power in collusion with the Americans. Adaf is not the first left-wing Israeli writer to give vent to his political nightmares in dystopian fiction. Here he describes an Israel that calls itself Zionist and is awash in Jewish symbols but which no longer possesses knowledge of the Jewish sources and history from which these names and symbols derive. As one character laments:

Yes, they tell us that their source is in ancient stories, but what precisely is the source? Our children inject the ten sefirot [in Adaf’s future the kabbalistic term refers to something between junk food and recreational drugs], we say House of David, we say Seed of Kings, and the words are filled for us with awe, weight, importance. Where do they come from, if we don’t really know from our own experience that awe, weight, importance? What is the meaning of this unending war with the Palestinians? Why are most of us in favor of this occupation?

Meanwhile, for reasons never fully explained, Shadrach throughout the novel uses technology to send his consciousness back to the 1980s, where he melds with the mind of Hanania, who is trying to help a neighbor look for her missing brother. These two parts of the novel seem arbitrarily fused, however, and for all of the novel’s lyric moments and occasional science-fiction pleasures none of the characters or their quests are convincingly realized. As one sees from the passage above, moreover, the political dimension of the novel is heavy-handed and simplistic.

Indeed, Shadrach is the latest in a series of novels by Adaf that are suffused with melancholy brilliance but feel disjointed and unfinished. In part this is because much of his work orbits around the untimely death of his sister; they are performances of mourning as much as or even more than conventional narratives with beginnings and endings. “In dreams I can see my sister, hear her,” says Shadrach, “but everything fades. If there were a way to draw up something from the past, to hold onto it, I would want to, I want to.” In trying again and again to apprehend an elusive past, Adaf produces poems disguised as novels. The futuristic technology of Shadrach—self-contained “evolution bubbles” and time-jumps into the minds of Sderot teenagers—seems above all an attempt to use sci-fi as a kind of objective correlative for his search for lost time.

In contrast to Adaf’s oblique references to the Bible, Dror Burstein’s novel Teet (Mud) retells in detail the story of the prophet Jeremiah. He does so, however, in an unsettling way. The setting is contemporary in that the events take place in a world much like that of today, with smartphones and airplanes, yet different in that prophets are common as public relations specialists, and Israel’s neighbors are Babylonians, Assyrians, and pharaonic Egyptians. Though the novel was an early nominee for the Geffen Award, it was not shortlisted, despite its literary merits, and it may fairly be asked whether this absurdist novel, despite a few fantastic elements such as a talking dog, is what we conventionally recognize as fantasy or science fiction. In that the story and actors are biblical yet the technology and mentality are modern, we might call Teet a science-fiction novel for Iron Age readers.

The novel delights in Jerusalem’s present-day topography. Jeremiah rides the light rail, King Yehoyakim resides in the Holyland apartment complex, and episodes are set variously at the Cinemateque, Teddy Stadium, and the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University. Yet everything is simultaneously defamiliarized, as the hipsters get their tattoos in Akkadian, the literary journals publish prophets alongside poets, and the Babylonian army makes its entrance in attack helicopters. While the story of Jeremiah has been an occasion for writers to make contemporary ideological statements—the Hebrew poet Y. L. Gordon turned the Judean king Zedekiah into an Enlightenment mouthpiece while Stefan Zweig gave voice to World War I pacifism in his drama Jeremiah—Burstein is mostly content to let Israelite and Israeli rub against each other and enjoy the heat generated by the friction. The novel will surely generate discussion when it appears in English translation later this year.

What is ultimately most striking about Teet’s take on Jeremiah, and where it falls entirely on the side of the modern, is the near-total absence of any experience of the divine. Prophets in this novel are poets, inspired less by the word of God than by the possibility of a good review. The biblical Baruch is transmuted here into an infamously intemperate literary critic who bashes Jeremiah over the head with his own computer keyboard.

Not long after reading Teet, I read Bible scholar James Kugel’s new book, The Great Shift: Encountering God in Biblical Times. Kugel argues that in asking why the palpably physical, shatteringly immediate encounters with God about which we read in the Bible become more distant, remote, and abstract as we move into the postbiblical (let alone modern) period, we should look not to God but to a changing sense of human self. This self grows progressively more “buffered,” to use philosopher Charles Taylor’s phrase—more self-sufficient, internally complex, sealed off from external forces. Prophets become poets, and poets find it difficult if not impossible to become prophets. Teet reads as a prooftext for Kugel’s book, a retelling of Jeremiah with modern, buffered selves.

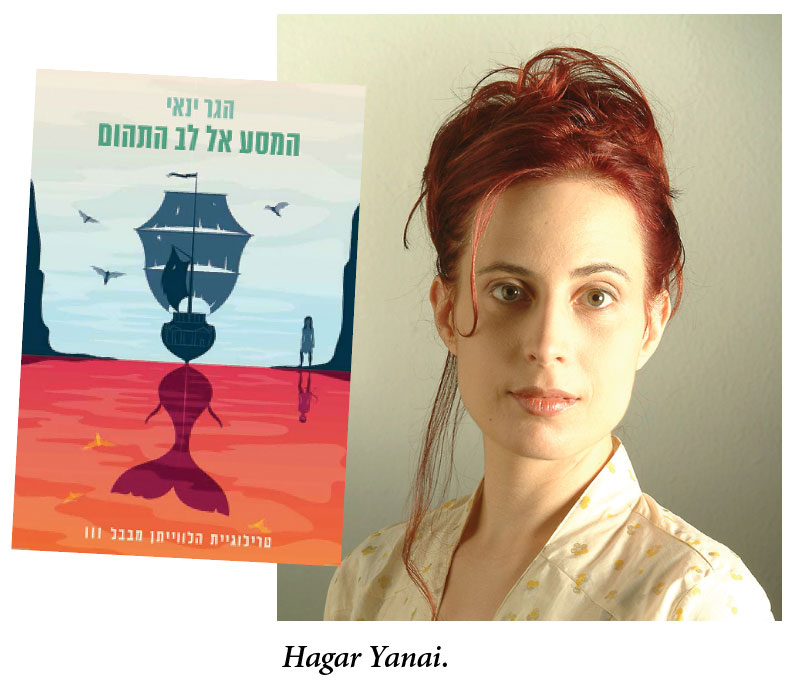

The ancient and the modern also come together in a book readers have waited nearly a decade to read. With Ha-masa el lev ha-tehom (Into the Abyss), Hagar Yanai has completed her young adult Leviathan of Babylon trilogy—the previous volumes appeared in 2006 and 2008—about the Israeli teens Yonatan and Ella, who enter a fantasy world populated by demons, princesses, and godlings and discover there the reasons for their father’s murder back in Tel Aviv. Way back in the inaugural issue of the Jewish Review of Books I expressed reservations about the first two volumes—admittedly, I’m not the audience for teen fantasy romance—but I have to say that I enjoyed the third book and found it both more satisfying and in some ways stranger than the earlier ones.

In this concluding volume Yanai makes most use of the Near Eastern mythologies with which she peppered the first two books. When the princess Nino (Yonatan’s crush) and the warrior Hillel Ben Shachar (Ella’s boyfriend) descend into the underworld as part of their world-saving quest, one understands that Nino is a version of the ancient Sumerian Inanna and Hillel a version of her sometime consort Tammuz, infusing the teen romantic drama and screwball slapstick with death-and-resurrection myths. More strange is the Freudian intensity Yanai packs into the book: Yonatan confronts his mother, who turns out to be the devouring abyss and only one of the book’s multiple mother-monsters; Ella, while disguised as her dead boyfriend Hillel, must battle a villain who is also the reincarnation of her father.

Yanai has left aside some of the stray plot ends of the first two books, likely in her determination to finish the task. She has also noticeably switched course between the second book, which presented the darkness of the abyss as a salutary psychic force to be embraced, and the third, in which the characters must resist its destructive allure. Whether or not this sunnier shift facilitated Yanai’s return to finish the series, one is grateful to see the completion of the first-ever Hebrew fantasy trilogy.

Yanai has left aside some of the stray plot ends of the first two books, likely in her determination to finish the task. She has also noticeably switched course between the second book, which presented the darkness of the abyss as a salutary psychic force to be embraced, and the third, in which the characters must resist its destructive allure. Whether or not this sunnier shift facilitated Yanai’s return to finish the series, one is grateful to see the completion of the first-ever Hebrew fantasy trilogy.

As an American reader, one is tempted to mine these novels for insight into the Israeli national psyche. Common themes exist among some if not all of these books: the fluidity of identity in our social media world, the nature of Israeli identity more specifically and whether it is something to be sought in the ancient past or the far future, escape from the body whether via technology or death, the power of imagination, and, of course, private detectives. Yet what we see here is mostly a varied and steady stream of speculation and play, and this is not a bad thing. Not every work of Israeli fantasy has to deal with specifically Israeli issues.

Consider, as a final instance, another book shortlisted for the Geffen Award. Ronit Dintsman’s children’s book Lev ha-ya’ar (Heart of the Forest) is set in the woods of the Carmel outside Haifa. Yet it is simply a fairy story, about the tiny sprites that protect the flowers and animals of the forest, an innocent importation of Disneyfied European folklore with nothing Israeli about it apart from the location. Well, it is true that the sorting of novice fairies into their proper units does have a whiff of army life about it. (The heroine, Lev, begins her career under the rather bureaucratic designation “Fairy Number 17.”) And when an evil witch in the forest begins abducting fairies, the fairy queen convinces her people to try negotiating, saying, “One makes a peace agreement with an enemy,” which happens to be what Yitzhak Rabin proclaimed during the Oslo process. Let’s hope things work out better for the fairies.

Suggested Reading

Remembering the Scholems

New books about Gershom Scholem and his brother Werner evoke memories of 28 Abarbanel Street in Jerusalem.

The Red Beret and the Rabbis

What has happened to the Religious Zionist rabbinate?

The Story They’ve Been Telling Themselves

“I wouldn’t turn on my beloved, my sacred husband,” Eva Panić firmly declared. Instead, she chose a brutal Yugoslavian prison–and abandoned her six-year-old daughter. David Grossman transforms their story into a disturbing yet beautiful novel.

The Chief Rabbi’s Achievement

Lord Jonathan Sacks is the most gifted expositor of Judaism in our day, and has written more than 20 books that are both learned and very accessible.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In