The Chief Rabbi’s Achievement

Robert Frost may be right when he says “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” but it isn’t the Jewish people. We love walls. The rabbis insisted on a siyyag la-Torah, a fence around the Torah to protect its laws, and we welcome requirements and boundaries. Walls insulate; they shelter; they keep in and keep out. Of course we don’t love walls when they no longer serve our purposes. Then we do what we can to render them more flexible, or move them. Despite rabbinic legends to the contrary, walls just don’t give. When we try to bend or move them, they tend to break.

This dilemma is at the heart of much of the work of Lord Jonathan Sacks, an Orthodox rabbi who has sought to work both within and beyond the walls that protect his faith. The most gifted expositor of Judaism in our day, Sacks has written more than twenty books that are both deeply learned and very accessible. From his perch as Britain’s Chief Rabbi—which he plans to leave in 2013 after 22 years—he has constantly endeavored to breach the walls separating Jews from one another, and Judaism from the larger world. Again and again, Sacks addresses the questions: how elastic can the tradition be? And at what point does ecumenism snap from the counter-pressure of authenticity? His latest work, Future Tense, reminds us of the scope and ambition of Sacks’ teaching, but also of its problematic character.

In Tradition in an Untraditional Age, one of his earliest books, Sacks rejects the “adjectival Jew”—the labels so many in our tradition seem to need. “Adjectives of ideology have no place in the ongoing life of Torah,” he writes. But the adjectives (and the walls they betoken) have long served many purposes and it’s hard to escape the implications of doing away with them. What Orthodoxy requires is precisely what Conservative and Reform Judaism reject. Unity for the Orthodox can mean nothing more than inclusion: The non-Orthodox are wrong, but still Jewish. Unity for liberal Jews, however, means pluralism, even allowing for significant differences between the Conservative and Reform movements. The Orthodox must affirm the legitimacy of non-Orthodox ideologies as authentically Jewish. But this is precisely what the Orthodox cannot do.

It is not only between but also within denominations that the question of legitimacy arises. Sacks repeatedly contrasts the positions of the influential 19th-century rabbis Samson Raphael Hirsch and Moses Sofer, the first, offering a more expansive view of the modern world, and the second a rejectionist one. The Cambridge and Oxford-educated Sacks cannot endorse Sofer’s stringencies. Still, the secular, materialist, and relativist assumptions of modernity undermine and threaten to sink Modern Orthodox efforts, of which Hirsch’s was one of the first. Sacks acknowledges the problem:

Can a synthesis be created between tradition and a culture so fundamentally at odds with it? The presumption must be that it cannot. If it cannot, then the choice lies between a religious modernism that breaks with tradition, or a religious tradition that disengages from modernity.

The limits to how far Sacks himself could go in bridging incompatible positions became painfully clear about fifteen years ago, following the death of the distinguished Reform rabbi Hugo Gryn. Sacks angered the left wing of British Jewry by refusing to attend his funeral and then proceeded to anger the right wing by speaking at a memorial gathering for him. The text of a letter from Sacks to another Orthodox rabbi, which was subsequently leaked, included Sacks’ denigration of the Reform movement and did nothing to calm the troubled waters.

Again and again, when he is caught in the middle, Sacks does what he can to make the best of the situation. “Judaism,” he says in Arguments for the Sake of Heaven, “is best understood not as a set of correct positions but as a set of axes of tension.” But such formulations only go so far. As the rabbis famously say about tefillin, the shel rosh (the head compartment) has four divisions, because each person’s thoughts differ, but the shel yad (the compartment placed on the arm) has only one, because Israel must act in unity. Tension and discord may persist in theology but if the community does not adhere to one standard of behavior, the traditional system collapses. “Judaism is not about the truths we know, but about the truths we live,” Sacks writes in To Heal a Fractured World. In a Jewish world divided between those who uphold halakha as a binding life system and those who do not, however, there is no unity in thought or action. Elevating tension to an ideal has a certain intellectual appeal but it is not a coherent program.

Is there a remedy for reconciling a fractured Judaism? Sacks’ answer seems, in part, to employ the strategy of many controversial Jewish thinkers before him: When there is restlessness at home, embrace the world. In times of dissension within one’s tradition, look beyond it—expand your worldview—and perhaps fret a bit less about internal frictions.

The world provides no escape from troubles, but at least it enlarges them so that one’s own strains are put in context, and so that Jews can export some of our best ideas and beliefs instead of just battling amongst ourselves. Jews do not relish being instructed by the world, but instructing the world has often been an unmitigated joy. Increasingly, it is Sacks’ role as Jewish pedagogue to British and Western society, and only less so his rabbinic writings, that seems to win him more admiration and esteem from his fellow Jews.

Sacks’ message to the world begins with the question of how Judaism has endured. In his new book Future Tense, he writes:

We can now understand a phenomenon that would otherwise be wholly unintelligible: how Jews survived in exile for two-thousand years. They did so because they were a society before they were a state. They had laws before they had a land. They had a social covenant before they had a social contract. So, even if the contract failed, the covenant remained. [emphasis in the original]

This distinction between a covenant and a contract is central to Sacks’ understanding of Judaism and how it has survived. He writes, “the logic of the covenant, unlike the social contract of the state, has nothing to do with rights, power and self-interest. Instead it is defined by three key words—mishpat, tzedek and chesed.” A covenant, unlike a contract, is not about dividing goods, but growing them. The covenantal goods to which Sacks refers—love, devotion, sacrifice—increase with partnership:

A contract is a transaction. A covenant is a relationship. A contract is about interests. A covenant is about identity. It is about two or more ‘I’s’ coming together to form a ‘We.’ . . . That is why contracts benefit, but covenants transform.

In other words, the covenant is the particular promise that instantiates universal goods. The covenant model is a small people’s gift to the larger world.

The covenant provides Sacks with his model of particularity and universality: Jews are members of a particular tribe with a universal message. Christianity, on the other hand, learned from Plato that truth resides only in universals. What is it that makes a table a table when one has four legs, another three; one holds food, another trophies? Plato’s answer is that all are reflections of the ideal table. In the ideal (the universal) resides the greatest reality. Thus, in Christian terms, the entire world should subscribe to the one true belief. By contrast, Judaism has remained stubbornly particularistic; salvation (or in Judaism, redemption), is not the preserve of Jews alone. There is one God but no one answer.

Judaism has always insisted on what Sacks, in his best book, calls “the dignity of difference”:

Biblical monotheism is not the idea that there is one God and therefore one truth, one faith, one way of life. On the contrary, it is the idea that unity creates diversity. That is the non-Platonic miracle of creation.

Even in his recent commentary to the siddur, Sacks pauses to note: “Judaism is the great counter-Platonic narrative in Western civilization.” We are Jews, in all our messy particularity, not proclaimers of great abstract truths, but devotees of the actual, champions of the quotidian. Halakha, the way, the law, not philosophy, is our characteristic expression.

In the Torah, diversity begins with Babel. Sacks writes that the tower’s collapse was our liberation; different languages, different traditions, a mosaic, not a melting pot—this is God’s intended design. Jews remind the world that truth resides not in universals to which all must subscribe, but in the clamorous human chorus. Sacks returns repeatedly to the historical irony that the more utopian the scheme, the more likely it is to crush actual human beings: “Universalism cannot tolerate the otherness of the other. It is the imperialism of the rationalistic mind.”

This lesson derives from the work of Sacks’ favorite philosophers, Isaiah Berlin and Alasdair MacIntyre. It echoes Berlin’s emphasis on the plurality of legitimate—and sometimes competing—goods that human beings desire, as well as MacIntyre’s lessons about the incommensurability of different systems of ethical reasoning.

Passover fits beautifully into Sacks’ counter-Platonic ideal of embracing difference. Like Michael Walzer, Sacks highlights the way in which the exodus has inspired numerous revolutions across the globe, and throughout history. In his Haggadah he writes:

There have been four revolutions in the West in modern times: the British and American, and the French and Russian . . . The contrast between them is vivid. Britain and America succeeded in creating a free society, not without civil war, but at least without tyranny and terror. The French and Russian revolutions began with a dream of utopia and ended with a nightmare of bloodshed and the suppression of human rights.

The Haggadah provides Sacks with some of his richest material. A universal God fashions a stubbornly particular nation. Only a monotheistic people, he points out, could have invented the synagogue, because one had to believe God was everywhere to build houses of worship in Babylonia and Britain. The pagan gods were without passports. Judaism is a particular people’s fidelity to a universal God, allowed for service to the One by innumerable paths.

In Future Tense, Sacks homiletically suggests that God chose the land of Israel as the setting for his people’s life precisely because it “is a place from which it is [geographically] impossible to build an empire.” Judaism is a critique of the imperial impulse, he writes. That is why Israel’s history has been different under the Jews: “Only under Jewish rule has Israel been an independent nation, not part of an empire.” And “it continues to be a major obstacle to the restoration of the Caliphate, the imperial dream shared by al-Qaeda, Hamas, and Hezbollah.” The Jewish insistence on the particular is always opposed to the imperial aspiration, whether military or philosophical.

This attractive portrait cannot erase a painful contradiction. What Sacks approves in the world at large is something that he cannot endorse within Judaism. In One People? Tradition, Modernity, and Jewish Unity, Sacks states his problematic credo: “Judaism is the religion of a particular people. From this, two consequences follow. It is inclusive towards Jews, and pluralist towards other faiths.” With this dubious stroke, Sacks decides that one people cannot sustain internal variety. But this is a conclusion that both Jewish history and much of Jewish philosophy, with its plurality of incompatible views, flatly contradicts. Moreover, it is a conclusion that I suspect he would be unwilling to apply to others. Can there be no pluralism among the French, Indians, or Serbs? Can there be no multiple forms of Chinese Confucianism? Only on Orthodox premises—God told us we must be this way—are Jews bound to reject pluralism. But then our obligation to act in a certain manner does not stem from the fact that Judaism is “the religion of a particular people.” Rather, the sticking point is God’s will. Presuming to outlaw other interpretations on the basis of one reading of God’s will—God does not wish us to be non-Orthodox Jews—is an ancient, venerable practice, but not much of a concession to the dignity of difference.

Preaching pluralism to the world and denying it at home is the perhaps inescapable, but still painful, paradox with which Modern Orthodox Jewish spokesmen must live. Those Orthodox thinkers who preach a genuine pluralism such as David Hartman and Yitz Greenberg, receive a very mixed reception in the Orthodox community, and Sacks, in several references to them, makes it clear that he wonders whether they have crossed a boundary that places them outside of Orthodoxy itself.

At times, Sacks permits himself simplicities: “Judaism,” he writes in his latest book, “is the voice of hope in the conversations of mankind,” and “surely, of all religions, Judaism emphasizes the work of God, not humans.” And, again: “No civilization, no faith has been as child-centered as Judaism.” These are the sorts of declarations that one might be able to get away with from the pulpit, but in cold print they read as boosterism. Surely there is a Tibetan, Russian Orthodox, or Jain voice of hope. Is there really no other culture, eastern or western, as focused on children as Jews? Does Judaism indeed emphasize God’s work more than does Christianity, more than Islam? These rhetorical excesses are born of a noble attempt to counteract the tremendous tide of abandonment of the Jewish tradition. At best, they can be regarded as overstatements on the part of a writer provoked to excess by the predicament he faces.

More important than his occasional susceptibility to platitudes is the fact that Sacks fails to do justice to the challenges presented by the modern study of religion. He appears never to risk a straightforward reckoning with biblical criticism. Sacks has been quoted as harshly attacking those who deny the Mosaic authorship of the Torah. But since modern criticism is the standard approach in virtually every non-Evangelical or non-Orthodox university in the Western world, it cannot be simply dismissed out of hand. For a thinker preoccupied with the widespread Jewish abandonment of tradition, ignoring the intellectual impact of comparative religion, history, archeology, textual criticism, and science leaves a gaping hole in the middle of his discourse. Sacks writes, “modernity forced faith into exile.” Yet, he does not allow his reading of Torah and the tradition to meet modernity on its most difficult terrain.

When Sacks does engage the Torah, on his own more congenial turf, he proves himself a masterful interpreter, whose comments illuminate both the text and human nature. Noting, for example, the Torah’s description of Moses’ radiance after he brought down the second set of tablets that he, not God, had carved, Sacks writes: “We are changed not by what we receive, but by what we do.” On God’s choosing to tell Abraham of His plan to destroy Sodom, Sacks suggests that this is a deliberate invitation to argue with the Divine.

He also has a gift for providing plausible, if not entirely sufficient, interpretations of the most problematic questions of theology. He interprets the akedah, the binding of Isaac, as God instructing Abraham that one can only treasure that which one is in danger of losing, a lesson taught throughout the Torah. And in a lovely and entirely characteristic comment on the messianic idea, Sacks writes: “that it stands in relation to Jewish history as the stars did to ancient navigation. As Kenneth Minogue notes, ‘when you steer by a star you don’t aim to arrive there.'” In one stroke, much of the implausibility and fantasy has been drained from messianism, and we are left with an image drawn from an Australian political theorist to illustrate a central Jewish concept. Sacks’ work is full of such gems.

Judaism today is without an influential, original Jewish philosopher who belongs in the company of Buber, Rosenzweig, Soloveitchik, Levinas, or Kaplan. But we are in desperate need of a fresh philosophy, an authentic redefinition of the boundaries of Jewish life and peoplehood. Despite his philosophical background and theological ideas, Jonathan Sacks has not forged a new philosophy. Yet, given his training and his gifts, perhaps when he is soon relieved of the burdens of the chief rabbinate, Rabbi Sacks will offer the comprehensive and compelling philosophy for which the Jewish world yearns. Certainly no one else is better qualified. In the meantime, he has presented a broad social and historical understanding of Judaism, studded with penetrating observations, and expressed with homiletic eloquence. In the spirit of the present season, one can only say dayyenu.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Suspecting Esther

For Seymour Epstein, the Megillah depicts the cycle of passivity and overreaction that is endemic to the diaspora.

The Professor and the Con Man

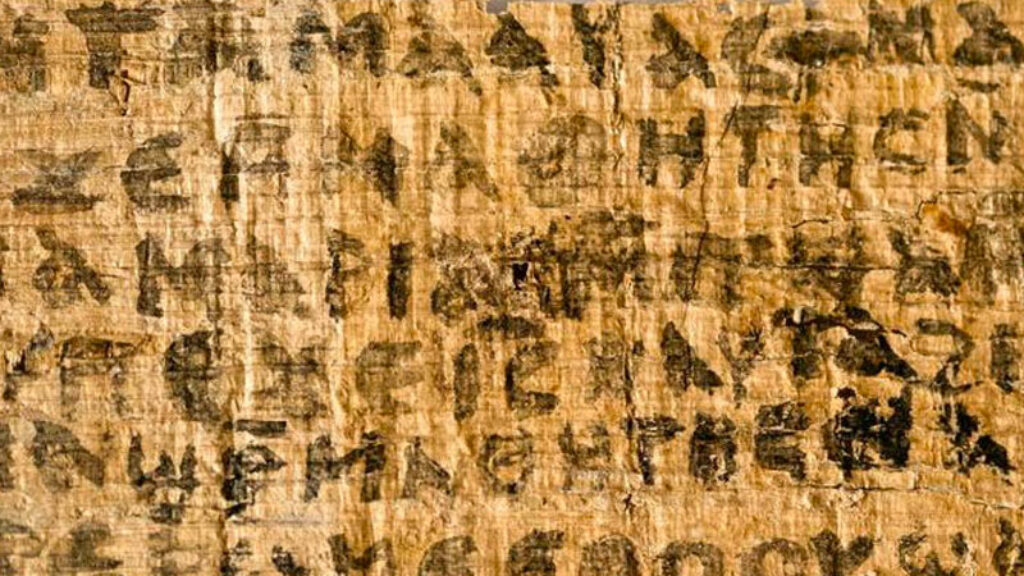

The saga of the papyrus that became famous as the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife began with an email sent to Karen King, a distinguished Harvard professor, in July 2010. The subject line read, simply, “Coptic gnostic gospels in my collection.”

The Lowells and the Jews

Robert Lowell, the most famous poet in America, icon of the antiwar movement, consummate Boston Brahmin, was especially glad to speak with a Jewish group because, he drawled, “I’m an eighth, you know.”

We Agree on Herzl

You know a review has turned mean-spirited when you’re indicted for crimes you quite carefully didn’t commit.

noam.zion

Excellent review, David.

Rabbi Sacks' critique of the rationalist universalism of Plato in favor of national particularism of Israel echoes what I heard many time from David Hartman zal. Because Judaism does not claim to be universalist or missionary in terms of particularist way of life, it necessarily validates other particularities. It precisely the totalitarian Platonist rationalism of Maimonides that makes him such an anti pluralist. As long as Orthodoxy does not universalize its own way of being Jewish or being religious by identifies its halacha with the truth, it necessarily leaves cognitive and normative space for other embodiments of halacha in other Jewish denominations.But if Judaism is only defined by halacha, then it needs for walls will necessarily be exclusive. It can share universal ethics and monotheism but can it share multiple halachic communities which are the identity boudnaries of its community?