WeShtick

One of the memorable details in Billion Dollar Loser, a new account of the rise and fall of the office-sharing company WeWork and its founder Adam Neumann, is a list of accoutrements Neumann’s family required for a company campout in 2018. The list includes three air conditioners, two fridges, a signature Range Rover and a Mercedes V-Class, three dinosaur-themed buggies, edamame packets, “4 Aesop Gardenia Shampoo,” and two bartenders. The document is so astonishing in its extravagance that any commentary would detract, and author Reeves Wiedeman simply prints it on four whole pages of his book.

The last part of the list is devoted to alcohol. The family was to be provided with two bottles of Highland Park whisky (thirty years old, at about $1,000 each), among other spirits, and also wine, twenty-four bottles of red and twenty-four of white—all of which, a reader of Jewish sensibilities might be mortified to learn, had to be kosher.

The story of WeWork’s crash, with its delectable details and doses of schadenfreude, has exited the business pages and entered mainstream culture via several podcasts and a Hulu documentary, but the fast-paced and entertaining Billion Dollar Loser is the most thorough treatment so far. Wiedeman, who first came to the subject when he wrote a skeptical profile of Neumann for New York Magazine, has an eye for the tawdry detail and a keen sense of the gap between the ditzy, do-good rhetoric of WeWork and the voracious practices that fueled the company into the start-up stratosphere and then, a heady decade later, sent it hurtling to earth. Judaism isn’t the focus of the book, but it’s an unavoidable presence throughout, the kosher wine being only one example. The WeWork story is a capitalist story, a moral story, and just a great story. But it is also, unfortunately, a Jewish story.

WeWork began in 2009 when Neumann, who’d come to New York from Israel after military service in the navy and knocked around for a while, opened a communal workspace in SoHo with a friend, Miguel McKelvey, an American from Oregon. Neumann’s wife, Rebekah Paltrow, a cousin of Gwyneth’s from Bedford, New York, was also in on the ground floor. With a hip aesthetic designed to appeal to the millennial workforce and with the remarkable ambition and charisma of Neumann as CEO, the company expanded across the world at warp speed, reaching a gargantuan valuation of nearly $50 billion before the balloon popped in 2019 with a spectacularly botched initial public offering.

If WeWork had been merely a rapacious business that failed, the story wouldn’t be much fun. The narrative electricity here comes from the loopy culture of the tech world, which requires its capitalists to speak a language of ideals—you are not out to make money, God forbid, but to connect people or save the planet or, as Neumann liked to say, “elevate consciousness.” (On the podcast WeCrashed, one of Neumann’s detractors had a good name for this: “yoga-babble.”) My own introduction to the phenomenon, around the same time WeWork was gaining steam, came when I was reporting on a press conference for the launch of an electric car made by an Israeli start-up that was going to change transportation forever and make the world green, or something. A reporter sitting next to me asked the CEO an innocuous question about how investors planned to make money. The CEO looked down from the stage as if he’d been asked about a recent case of syphilis and informed us, “I work for your children.”

WeWork wasn’t really a tech company, but it played one in the market. Neumann liked to tell investors from venture capital funds that he wasn’t in the business of renting office space; he was cultivating a “physical social network” that was going to encompass an entire world of “We.” The company’s communal office spaces would be joined by WeLive apartment buildings, WeGrow schools, and then by WeNeighborhoods and WeCities. Eventually, the company would transform education and help save the rainforest (even buying one in Belize for that purpose) and also, maybe, save orphans in India. Those parts were more or less generic, but Neumann employed two specifically Jewish ideas: the kibbutz and the Kabbalah.

The liberation of the Jewish people will be brought about by the workers’ movement, or it won’t happen at all,” wrote Ber Borochov, father of Labor Zionism. “The labor movement has only one weapon at its command: the class struggle,” he wrote, and the future Jewish state would be a solution not only to homelessness but to the exploitation of workers by capital. His ideas helped produce the kibbutzim, which were dedicated, at least in theory, to radical equality. One of those communities was Nir Am in southern Israel, where Adam Neumann spent a few years as a teenager. (Incidentally, for most Israelis, it’s Adam’s sister, Adi, a model, who’s probably still the more famous sibling.)

As Neumann reinvented himself in America as a visionary CEO, with a certain Israeli mystique working in his favor, he made much of his kibbutz background. WeWork was a community, a kind of capitalist collective. People renting desks weren’t tenants but “members.” They’d share resources like coffee machines, printers, and fruit-flavored water and have unplanned yet productive meetings in the corridors. Sure, they were paying, but that wasn’t the point—the point was We. It was, he told Ha’aretz, “Kibbutz 2.0.” Neumann’s kibbutz identity was part of his personal brand to such an extent that when puzzled onlookers spotted him walking barefoot on a Manhattan street, raising questions about his mental health, one of his publicists explained, “He is a kibbutznik.”

WeWork’s own employees worked long hours for subpar salaries. They were motivated by the company’s genuine energy (in December 2019 alone, it opened fifty-two new buildings across the world), by pep rallies with call-and-response chanting (“I say ‘we,’ you say ‘work!’”), and by the glimmering promise of stock options. The company was like a family, they were told, so leaving at a reasonable time to see your actual relatives was disloyal.

It was a strange kind of family. The janitors’ union protested WeWork’s labor practices, some restrictive clauses in employee contracts were deemed illegal, and it eventually emerged that Neumann was not only renting properties to his own company, he was renting the use of the “We” brand to the company as well, for millions of dollars. He’d also cashed out hundreds of millions in WeWork stock over the years, a strange move for a confident CEO. When WeWork finally went public, we learn from Wiedeman’s book, the paperwork revealed that the company “had undergone a legal restructuring that lowered the tax rate on stock owned by Adam and other executives to a rate below what WeWork’s rank-and-file employees would have to pay.”

Wiedeman is rightly unsparing about all of this, but he rarely strays from a laconic reportorial tone well suited to material that needs no embellishing. He quotes Rebekah Neumann saying in an interview that she and her husband believed “in this new asset-light lifestyle,” and that she was a “hippie” who wanted “to live off of the land.” Meanwhile, the couple used a $60 million private jet and had recently bought their fifth home. Just like the kibbutz!

One unlikely figure to be inspired by socialism at the heyday of the kibbutz movement was Ber Borochov’s contemporary Rabbi Yehuda Leib Ashlag, a mystic who was born in Poland and arrived in Jerusalem in the 1920s. “I admit that I see the socialist idea, which is the idea of equal and just distribution, as the most true,” he wrote, and the Marxist method as “the most just of all of its predecessors.” The perverted implementation of Marxism in Soviet Russia showed that humans weren’t yet ready, the rabbi thought. But the socialist slogan “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs” was true, a glorious counterforce to egotism, the “hatred and exploitation of others in order to ease one’s own existence.” He thought Marxism and the Kabbalah had some similar ideas and could help elevate us all, as a WeWork PowerPoint might put it, from me to We.

Some adherents of Ashlag’s doctrines went on to found a kind of kabbalistic kibbutz, Or HaGanuz, a scrappy community of a few hundred people in northern Israel. An American follower, Rabbi Philip Berg, took a different route, founding the Kabbalah Centre, which rebranded the Jewish mystical tradition as a kind of “technology for the soul” that anyone could download. Eventually, there was Kabbalah merch, including red-string bracelets of the kind traditionally offered by mendicants at the Western Wall—which the Centre sells for $26. It also provided spiritual counseling and networking opportunities, solicited celebrities, and eventually claimed members such as Madonna, Demi Moore, Donna Karan, and Adam Neumann.

The Kabbalah Centre makes appearances throughout the WeWork story, whether in references to “light” and “energy” sprinkled through Neumann’s pep talks or in counseling offered to executives by one of the organization’s rabbis, Eitan Yardeni. According to Wiedeman, it was Rebekah who introduced her husband to Kabbalah (having first taken him to a yoga teacher who happened to be Uma Thurman’s brother). Early on, in 2011, a potential employee remembered coming in for an interview and speaking with both Adam and Rebekah about “the Neumanns’ embrace of Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition, and how spirituality had come to play a role at WeWork.” We learn that WeWork sought an oddly specific sum in debt financing: $702 million. They arrived at that number by taking Adam’s age, thirty-nine, and multiplying that by eighteen, a propitious number in Jewish tradition that has the numeric equivalent of the word chai, or “life.” At one point, Neumann appeared at a Jewish fundraiser in a black yarmulke, encouraging everyone to “be the full light that we can be” and promising that if that happened, “there would be no stopping us, there would be peace in the world, and Moshiach would be here.”

At a crucial point in his corporate odyssey, Neumann was nearly saved by his own messiah, the Japanese tech investor Masayoshi Son, founder of SoftBank. Masa, as he’s known, met Neumann for half an hour, was enchanted, and eventually pumped billions into WeWork, hypercharging the CEO’s reckless growth and spending. The two seemed to share a utopian vision that matched their egos, along with the idea that running a solid business simply wasn’t big enough. By 2300, Masa suggested, SoftBank could be a “telepathy company instead of a telecommunications company.” Kabbalists—real ones, anyway—aim to do more than just raise people’s morality a notch or two, and the kibbutz wasn’t just trying to build a better dairy barn. These are grand visions seeking the transformation of humanity, and in that regard, at least, Neumann was a legitimate heir to both traditions.

Whether he actually believed any of it, or simply professed whatever worked as he went about the sordid business of making money, is one of the question marks at the center of the story. Neumann didn’t cooperate with Wiedeman, so we get his public persona but no real access to his thoughts. With all the yoga-babble and self-regard (he decorated his office and conference room with huge photographs of himself surfing), Neumann certainly makes a satisfying literary villain. I’m a bit suspicious of villainous portrayals that are too satisfying, however, and think it’s safe to say that this picture probably lacks a few angles. For example, Wiedeman quotes a former executive’s description: Adam, Francis Lobo said, is “one-quarter crazy, one-quarter brilliant, and the other half is a fight between his ego and genuinely caring for people.” But the book doesn’t give us any of those positive halves or quarters. And Billion Dollar Loser is similar to the other WeWork treatments in relegating Neumann’s less colorful (and non-Jewish) cofounder, Miguel McKelvey, to the margins, as if he wasn’t there all along, making decisions and getting fantastically rich.

If we could resurrect Ber Borochov and Rabbi Ashlag and ask their opinion about all of this, what would they say? The socialist, we can assume, would be miffed to see the name of the kibbutz taken in vain and spattered with capitalist mud. The kabbalist might struggle to understand the red-string bracelet on the wrist of the guy with that infamous camping list. But when presented with the facts of this very human story of greed, ego, and gullibility, one senses that while both would be disappointed, neither would be surprised.

Suggested Reading

The Book of Radiance

Daniel Matt’s massive new English edition of the Zohar is not only a great translation, it is also one of the great commentaries on the classic work of Jewish mysticism. Insofar as it is possible, Matt has brought the unfathomable, mysterious, and poetic depths of this “book of radiance” to the English reader.

The Kibbutz, Post-Utopia

One hundred years ago, Yosef Bussel, Yosef Baratz, eight other young men, and two young women arrived in Umm Juni on the southern shore of Lake Tiberias. There they established a kommuna, a small agricultural settlement that was to become the first kibbutz. A new Hebrew book celebrates the centennial history of this great experiment.

The Kibbutz and the State

How the position of the kibbutz in Israeli society has changed, and why.

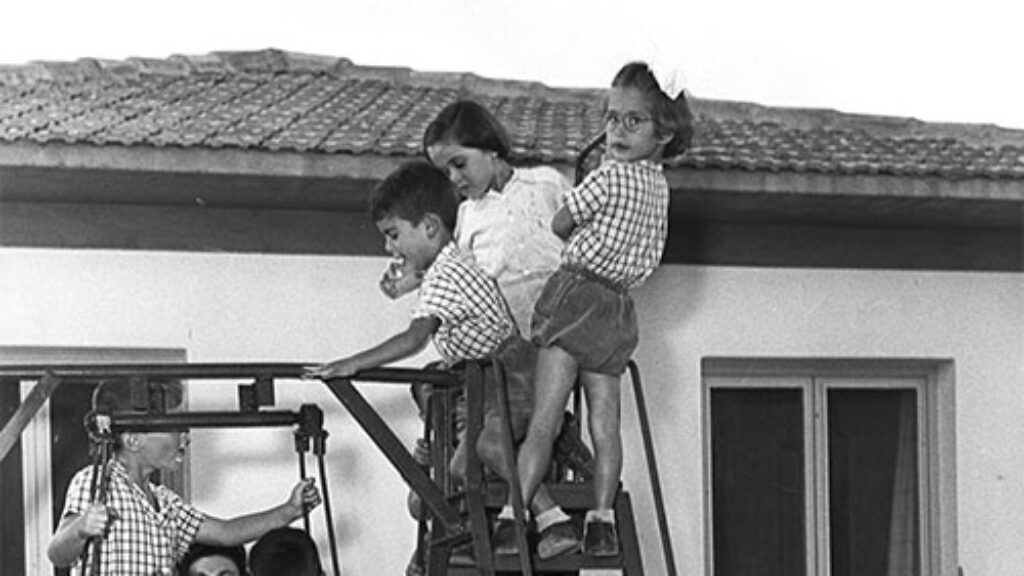

History of a Passé Future

At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In