Jews in Trench Coats

Since 9/11, forests of trees and oceans of ink have been sacrificed in the production of books on terrorism and intelligence. It is impossible to keep up with them, which is not really a hardship as they tend to be weak, bleak, and uninteresting. They are generally written by intelligence insiders, and most of us are professional pessimists by both training and by inclination. We have all marched into briefing rooms, bright eyed, bushy tailed, and armed with our maps, our PowerPoint slides, and our satellite photos, only to be begged by some haggard undersecretary or assistant deputy minister, “Can you please just tell me something encouraging for a change?”

So Douglas London’s The Recruiter is a rare treat, a book that captures the essence of intelligence work while remaining interesting. London, a Jew (this will not prove to be irrelevant), spent three decades as a CIA case officer. Case officers labor about as close to the intelligence coalface as it is possible to get. Almost always working in hostile countries, under either diplomatic or commercial cover, the case officer’s job is to recruit and handle agents—people who, whether for money or principle, choose to betray their country by going to work for a foreign intelligence agency.

The risks—exposure, arrest, torture, a bullet in the back of the head—are huge, for both parties to the transaction. But despite the billions, even trillions of dollars that intelligence agencies spend collecting signals intelligence—everything that’s communicated via computers and cellular and radio technology—it’s human intelligence that lies at the heart of the enterprise. I used to tell aspiring intelligence officers and analysts that it was far better to do good analysis on messy human source data than bad analysis on some comprehensive electronic data set. “Human beings hold the ultimate key to intelligence,” London tells us, in characteristically lucid prose. “But until such time as we can develop a technology to read hearts and minds, we still need to learn the secrets that lay hidden in their souls.”

The rewards of London’s career do not blind him to the reality of the world in which he moved. He can see his own agency with a clear eye, and his worm’s-eye view of the CIA post-9/11 makes for a sobering read. He chronicles the politicization of not only the CIA but the entire US intelligence community in grim detail. Extraordinary pressure from an administration eager for war meant that human sources were tasked beyond their capabilities, and analysis and reporting were sometimes cherry-picked to suit the temper of the day. This, as we all know, contributed to the weapons of mass destruction “slam dunk” (as then-CIA director George Tenet put it) and the quagmire of Iraq.

Nor have things gotten better, according to London. In the conclusion, he writes of the recent CIA director’s “obsequious compromises” and willingness to be President Trump’s “cheerleader while indulging his maligning of the Agency’s integrity.” All intelligence agencies struggle with ambient political expectation. For the CIA, it may be a losing battle.

Perhaps all old intelligence warhorses look back to a time before the fall when, we like to think, our agencies were pure and our missions were clear. My own former agency, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, has been rocked by revelations of serious bullying, harassment, and sheer incompetence as well as the actions of a senior official (and former colleague) who is accused of passing highly classified allied intelligence to a criminal organization. Maybe there never was a golden age. But when agencies begin to crumble, whether under the weight of politics or their own internal demons, it is time for a serious public debate about what intelligence is, what it is not, and what role it plays in a democratic society.

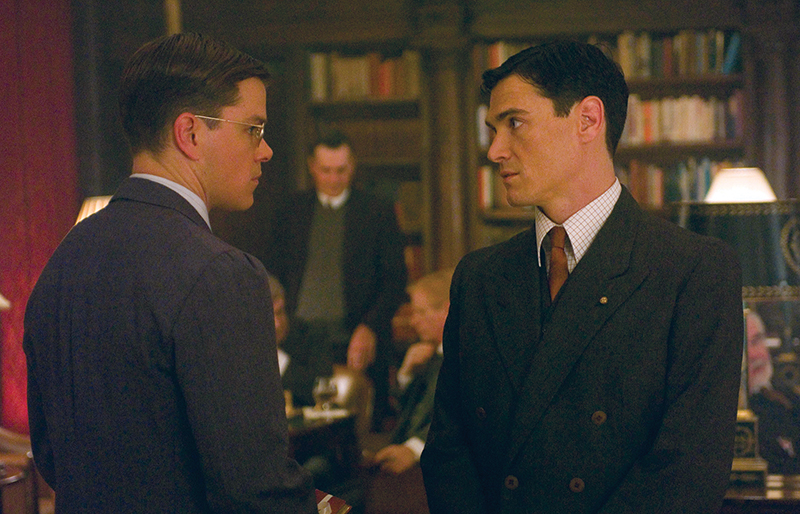

The CIA has a reputation as a bastion of those whom Lenny Bruce once described as “heavy goyim—dangerous” (although, in fairness, he was talking about the Marine Corps, in which London also served). This perception is no doubt influenced by people such as Allen Dulles and films like The Good Shepherd. Even after my own intelligence career exposed me to the present agency’s more complex reality, in my imagination, the halls of Langley are still haunted by Yalies and other WASPy East Coast types.

In large measure, this was the reality of the CIA into which London was recruited. When he completed his initial training, London set his sights on CIA’s Near East and South Asia Division, known as NE. With the Soviets in Afghanistan, the Iranian revolution still fresh in America’s collective memory, and Hezbollah on the rampage across the Middle East and the Mediterranean, NE was by far the most exciting place in the agency to be. But almost as soon as he got there, he was told that the Arabic-speaking case officer cadre known as the “NE mafia”—almost all pro-Palestinian Arabists—“would not likely take to the idea of having a Jewish case officer in their fold.” Another senior member of NE called young London’s loyalty into question, asking him if he was required to support Israel. “When you go to the synagogue, by the rabbi, isn’t it a religious requirement?”

As it turned out, London was selected for NE nonetheless and had a happy career there. But for large parts of it, the exigencies of the job required him to conceal his personal religious identity not only from targets but from the US officials and public servants with whom he worked. “I soon came to realize,” he says, in one of the most poignant passages in the book, “that keeping my religion in the closet eased my ability to establish friendships among many colleagues, and superiors, who tended to hold anti-Semitic, or at least negative perceptions, of American Jews.” Even his own children did not know that they were Jewish.

London’s experience as a Jew in the world of Western intelligence resonated with me. For more than thirty years, I worked intelligence for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada’s analog of the FBI, where Jews were even scarcer than at the CIA. And that’s to say nothing of women, minorities, or members of First Nations. I don’t have a particularly Jewish name, or even a particularly Jewish look (whatever that is), and I was never undercover, so I didn’t try to conceal the fact of who or what I was. But I was taken aback by the casual antisemitism that I encountered among some of my supposedly well-educated, well-traveled colleagues. “I hope you won’t be offended by me saying this,” an early boss once said to me of a potential hire whom he had summarily rejected, “but she was a real Jewess, if you know what I mean.” I sure did, and I wasn’t sure whether it was the attitude that bothered me most or the fact that he was looking for insider validation of just how pushy and shrill those Jewesses could get.

But for all that, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police was always imbued with a kind of blue-collar pragmatism. As a Jew among real heavy goyim, I was more of an exotic than a figure of suspicion or distrust. And being a Jew actually worked well for me during a long period in my career when I was on the Eastern European Organized Crime desk. With a yiddishe kop and some facility in Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew, I was able to get inside the heads of our targets and, in a few cases, establish a degree of rapport with them.

After 9/11, I entered the world of national security and counterterrorism, which meant focusing on the Middle East and South Asia almost exclusively. That’s where my experience paralleled London’s. Like him, I discovered that the resident Arabists tended to view Israel as a kind of parvenu blight on the Arab world and were reflexively suspicious of Jews who trespassed on their preserve. Their younger colleagues, meanwhile, cleaved firmly to the notion of Israel as a brutal colonial power engaged in a genocidal war against Palestinians.

In 2008, a senior Canadian diplomat was kidnapped and was held for a nightmarish 130 days by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb before being saved through the considerable efforts of my agency, among others. After his safe return, he excoriated the Canadian government for its “scramble to lock up the Jewish vote” and its “unproductive support of Israel” that “undermined Canada’s reputation in the Middle East.” I may be wrong, but somehow it seemed that this man’s kidnapping and ill-use by a violent Islamist extremist group was in some ineffable way the fault of Israel and Canadian Jews. Many of my colleagues agreed.

On a personal level, this clubby, old-school antisemitism often manifested in questions, spoken and unspoken, about my judgment on matters related to the Middle East and Islamist extremism, especially in interagency situations. I was often jokingly referred to as “the Zionist agent” and not so jokingly told that my opinions carried little weight because as a practicing Jew, I had to be an Israeli sellout. An amazed Arab Canadian intelligence officer whom I liked and respected once said, “Man, you can’t catch a break—those guys just keep deferring to me, and for all they know, I could be al-Qaeda!”

Ironically, my interactions with Muslim community leaders were far more positive. Almost invariably, they were disarmed by the revelation that I was Jewish and would open up to me as someone with a unique relationship to Islam. “Really,” I was assured by one imam with a reputation as a firebrand, “despite everything, we are brothers under the skin, you and I.”

I can’t truly say that antisemitism adversely affected my career—like Isaac Babel, another Jew with spectacles on his nose and autumn in his heart, I got to ride with the Red Cavalry. I suspect London would say the same thing. Proof of this is that he succeeds where few intelligence memoirists do. He captures the joy of intelligence work, because really, as London says, “As serious of a business as it is, with the high stakes of lives on the line, God forgive me, it is incredibly fun.”

Some of that fun, especially for graduates of “The Farm,” as the CIA familiarly refers to its clandestine operations training depot at Camp Peary, Virginia, involves the obvious—jumping out of airplanes, handling exotic weapons, tactical driving, and so forth. But for most of us, the real fun lay in the deeper pleasures of the job.

Intelligence officers and analysts have a privileged view of the making of history; sometimes, they even get to participate in it. They see and experience and come to know the world in ways that nobody else can; they are privy to its secrets. But mostly, they experience humanity, in all its beauty and all its ugliness. Looking back at a lifetime’s worth of agents, sources, and informants, more than a few of whom were deeply disturbed and dangerous people, London recalls that they were “all at once human and inhuman, but terribly real and entirely authentic.” Intelligence work allows us to bring our best human and intellectual capabilities to bear in service to our country. “Real spies persuade,” London says, “thugs coerce.”

London is a smart, persuasive, and charming guide to what, for most people, is a hidden world. It is hard not to like and trust him. That’s probably what made him so successful at his job.

Suggested Reading

A Spy’s Life

Sylvia Rafael: The Life and Death of a Mossad Spy opens not with an intrepid secret agent about to pull off a bold maneuver, as books with such titles usually do, but with nine men gathered around a table in 1977, studying a picture of an Israeli agent.

Of Spies and Centrifuges

Jay Solomon traces decades of spy games between the United States and Iran, a conflict, he writes, “played out covertly, in the shadows, and in ways most Americans never saw or comprehended.”

Orphan Soldiers

When WW II seemed all but lost, Britain knew that it had to take impossible risks, including turning Jewish refugees into crack commandos.

Our Man in Beirut

The Arab Section, suggests Matti Friedman, in one of his latest book's nicer lines, “needed men idealistic enough to risk their lives for free, but deceitful enough to make good spies.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In