Satmar, American-Style

“Only a short ride away, yet seemingly centuries back in time, is a Hassidic ‘shtetl,’ where the orthodox Jewish population still tries to live as it did before the Holocaust.” So claimed USA Bike Tours in a description last year of its guided tour “The Delights of Brooklyn,” describing the Satmar community of Williamsburg. New York Magazine said virtually the same thing of the suburban Satmar village Kiryas Joel: “a Jew could live as he did in eighteenth-century Europe.” Two excellent, ambitious books, both of them cowritten, have recently appeared to challenge these common, even hackneyed, perceptions.

In A Fortress in Brooklyn, Nathaniel Deutsch and Michael Casper write that “rather than an eastern European shtetl miraculously transported to Brooklyn, the Hasidic enclave in Williamsburg is a distinctly American creation, and its journey from the 1940s to the present a classic New York City story.” It is a story about urban real estate, ethnic politics, welfare, and urban renewal.

Nomi M. Stolzenberg and David N. Myers’s American Shtetl examines the emergence and evolution of Kiryas Joel and the protracted legal battles it has fought to preserve its self-segregation. Their book turns the classic narrative of Jewish Americanization, epitomized in the title of Seymour Leventman’s classic 1969 essay, “From Shtetl to Suburb,” on its head. For what the Satmar leadership aimed to create in the suburbs was a shtetl. But it was “a decidedly American one.” For all its ostensible alienation from American values and American culture, Stolzenberg and Myers write, Kiryas Joel “arose because of, not despite, the American political system.”

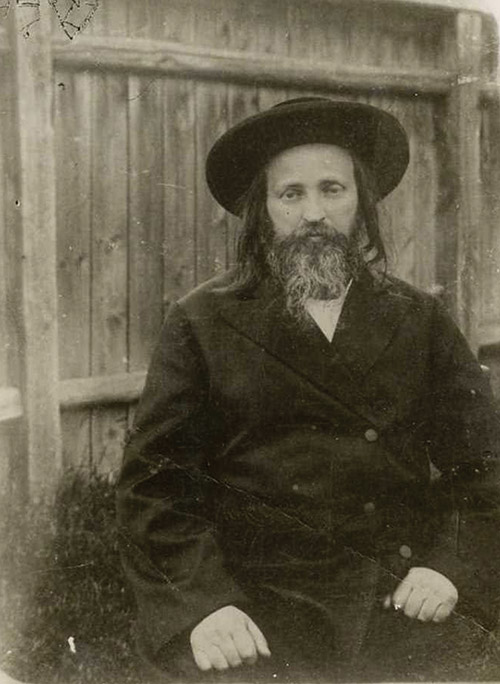

Satmar is the largest Hasidic sect in the world today; it is also one of the newest. Its founder, Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, popularly known as Reb Yoelish, was born in 1887 in what was then Sighet, Hungary, to a father who was the rabbi of the city. When his father died and his brother succeeded him, a seventeen-year-old Teitelbaum moved to Szatmár (today the Romanian Satu Mare), a city that contained some five thousand Jews. There, through force of personality, fierce devotion to Torah study, and ardent advocacy of a religious purity that required segregation from both Gentiles and the vast majority of Jews, he attracted a growing following. As Stolzenberg and Myers note, Satu Mare bore little resemblance to “the mythic Eastern European shtetl.” It was a city where Jews accounted for only 20 to 25 percent of the population. Moreover, they were religiously diverse, including reform-oriented Jews as well as Hasidim and even some eight hundred Zionists, who were Teitelbaum’s bête noire.

Given his hatred of Zionism, it is ironic that Teitelbaum survived the Holocaust largely thanks to the intervention of a Hungarian Zionist official named Rudolf Kasztner. In 1944, as the Nazis were deporting the Jews of Hungary to Auschwitz at breakneck speed, Kasztner began negotiating with Adolf Eichmann to exchange as many European Jews as possible for cash, gold, and matériel. Although Kasztner’s plan failed, he managed to extract a promise from Eichmann to allow for a train that would transport more than 1,600 Jews to a neutral country. Teitelbaum was on that train.

After the war, Kasztner was accused by some of being a collaborator and sued for libel, in one of Israel’s first great political controversies, leading to the fall of Prime Minister Moshe Sharett’s governing coalition. Kasztner was assassinated in 1957 outside his Tel Aviv home by three veterans of the so-called Stern Gang. Teitelbaum himself was not untouched by this controversy. As Stolzenberg and Myers write:

Joel Teitelbaum’s devoted biographers go to great lengths to herald his efforts to rescue Jews in Hungary. The resulting portrayal stands in sharp contrast to the image of a charismatic religious leader who was saved by virtue of his own renown, but left behind his followers in a time of grave crisis. Indeed, there are those who still recall being told by Rabbi Teitelbaum to remain in Europe into the 1940s rather than seek refuge in Palestine. So great was the sin of abetting the Zionist enemy, they recall being instructed, that it was better to remain in Europe in the hope of divine salvation.

Despite his fanatical anti-Zionism, after the war Teitelbaum obtained a certificate to move from Switzerland to Palestine. A year later, however, he left Palestine and settled in the United States. According to his later hagiographers, this was so he could rid America of its “spiritual impurity.” More critical scholars note that he had failed to create a Hasidic community in Jerusalem, in part because of his suspect behavior during the Holocaust. Whatever the reasons for his move, both the hagiographers and the historians agree that Teitelbaum’s efforts to rebuild a Satmar community on American soil proved a striking success.

Teitelbaum arrived in New York at a time when the city’s Jewish population had reached its peak of roughly 2.25 million. Although he spoke of creating “a camp in the desert” (Num. 10:31), Williamsburg was hardly a Jewish wasteland. Many of its Orthodox Jews initially welcomed the arrival of Teitelbaum and his Hungarian Hasidim, believing they would help rejuvenate a community that was just starting to lose Jews to the suburbs. Teitelbaum, however, had no intention of partnering with his Jewish neighbors in Williamsburg, not even the Orthodox.

For Deutsch and Casper, what distinguished the Hasidim of Williamsburg above all was their refusal to follow their fellow Jews and other white ethnics in the 1950s and 1960s in abandoning Williamsburg even as the neighborhood became increasingly infamous for its poverty, crime, and deterioration. In fact, the Hasidim largely welcomed the emptying out of Williamsburg’s Jews and their replacement by Puerto Rican and African American migrants to the city. Precisely because they saw the gulf between themselves and the Hispanic and black people as so profound, they worried less that the culture of the newcomers could lure young Hasidim away from their cloistered community.

Nonetheless, Deutsch and Casper argue, “in certain important respects, including speech patterns and their relationship to space, Hasidim in Williamsburg came to resemble their Puerto Rican and black neighbors more than their fellow Jews in the suburbs.” Because of their high birth rates, relative lack of secular education, and resultant high poverty, the Hasidim also came to be classed by their detractors as the “undeserving poor,” a stigma they shared with their new neighbors. By the 1950s, public housing had become racialized as black and Hispanic. But this did not deter the Hasidim from doing everything possible to obtain units in the newly built apartments in Williamsburg that were big enough to accommodate their large families.

The issue of public housing epitomized the ambiguous identity of the Hasidim. On one hand, the New York City Housing Authority offered the Hasidim incentives to settle in the two new projects as part of a “policy to attract and retain white residents at a time when the number of blacks and Puerto Ricans in public housing was skyrocketing.” On the other hand, their indigence, their continued concentration in a dilapidated and crime-ridden neighborhood—indeed their very desire for public housing—qualified their whiteness. By the 1980s, Hasidic activists successfully lobbied the US Department of Commerce to classify Hasidic Jews as a “disadvantaged minority group,” thereby “transforming their enclave into one of the largest recipients of certain kinds of federal and state aid to the poor in New York.”

Deutsch and Casper take such maneuvering as a sign of the urban savvy of the Satmar Hasidim, whose success in working the system reflected their “commitment to extreme ideological purity, on one hand, and a remarkably flexible pragmatism on the other.” They also clearly admire them for being willing to live alongside Puerto Ricans and African Americans, in contrast with the “many liberal critics of racism who nevertheless resided in highly segregated suburbs and would never have dreamed of setting foot in public housing.” Even the resort of some Satmar Hasidim to vigilante violence against their neighbors in the late 1960s and 1970s is taken by Deutsch and Casper as proof of their resolve to fight to preserve “the safe haven they had painstakingly created in Williamsburg.”

Beginning in the 1980s, new challenges arose for the Hasidic haven of Williamsburg. First came the artists, who were attracted to the deserted warehouses along the East River, available at rents far below those of the East Village or elsewhere in Manhattan. Then came the hipsters, who were drawn to the “gritty authenticity” of Williamsburg but, unlike their forerunners, brought with them “entertainment and leisure activities.” By the 2000s, it was the hipsters’ turn to be “priced out of the neighborhood by newer residents who worked in the city’s booming financial and real estate industries.” Williamsburg had gone “from a place where New York City literally dumped its garbage to one of its most sought-after sites for luxury development.”

Many Hasidim ardently opposed this invasion of the artistn—a term they came to use to refer to the artists, hipsters, and wealthy gentrifiers alike. They viewed the “largely white, middle or upper class, post-ethnic, and—at least overtly—nonreligious” gentrifiers as threatening the “fortress” they had created to ward off assimilation and defection among their ranks. Satmar Hasidim pictured their fight against them as a reprise of the Jewish zealots rebelling against the ancient Romans. Unlike the Latinos and African Americans, “whose explicitly nonwhite identity represented a racial ‘step down’ for the racially ambiguous Hasidim,” their new neighbors “embodied a racially and economically privileged identity that was potentially accessible to younger Hasidim,” if they were willing to change their clothes, hairstyles, and aspirations. In short, the lifestyle of their new bohemian or bourgeois neighbors was a tempting advertisement to take the “off-the-derekh” off-ramp.

At the same time that some Hasidic activists were fighting gentrification, others were gentrifying. Starting in the late 1990s, with housing stock increasingly limited within the Hasidic borders in Williamsburg, members of the community began purchasing and developing property immediately to the south in the northern parts of the traditionally black neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Clinton Hill. This “New Williamsburg” featured “new, spacious, well-appointed apartments designed to serve every need of a young Hasidic family.” The businesses that opened there in the 2000s and 2010s, from gourmet kosher supermarkets and sushi bars to wellness centers, catered to “the emerging Hasidic bourgeoisie,” whose lifestyle “owed more to contemporary trends in consumption than to traditional Satmar conceptions of piety.” New Williamsburg, Deutsch and Casper say, was yet another rejoinder to “the oft-repeated claim that Hasidic Williamsburg was an unchanging island or premodern shtetl in Brooklyn.”

Deutsch and Casper ultimately view the Satmar refusal to abandon its Brooklyn neighborhood through the urban crisis and contemporary gentrification as “one of the great New York stories of the past century.” “Williamsburg’s Hasidim,” they claim, “were among the only Jews in the country who retained the urban sensibility and swagger that had characterized Jews since the dawn of the modern period.” However, as Deutsch and Casper acknowledge, Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum had contemplated creating a suburban village to preserve Satmar purity as early as the late 1950s.

Kiryas Joel (the City of Joel) was established in the Hudson Valley town of Monroe, New York, in 1974. Its population now comprises roughly thirty-three thousand residents, 99 percent of them Satmar. One plausible projection holds that Kiryas Joel will have as many as ninety-six thousand residents by 2040, which would, Stolzenberg and Myers note, make “it the first all-Hasidic city in the world.”

A “jurisdiction governed by Jewish law,” as defined by the Rebbe and his associates, it has been enmeshed in legal conflict with its neighbors, along with others troubled by its putatively theocratic character, from the outset. The strife began in the mid-1970s over exclusionary zoning laws. Residents of Monroe, who had sought to maintain the rural character of the town by restricting residences to single-family homes, were alarmed when it became clear that agents serving as fronts for Satmar were planning to construct garden apartments and multifamily residences in Kiryas Joel, notwithstanding their protestations to the contrary. In 1977, the Satmars successfully turned Kiryas Joel into its own legal municipality and freed themselves from Monroe’s zoning laws, but that brought new problems and conflicts.

Virtually all of Kiryas Joel’s families attended private religious schools in the village. However, as “one of the poorest communities in America,” the town didn’t have the resources to deal with its children with special needs. Consequently, it insisted that the local school district provide these students with the necessary services, as required under state and federal law, while respecting the community’s rejection of coed education. Since Satmar Hasidim voted as a bloc, they had substantial political clout and managed to persuade the New York State Legislature to create a public school district within Kiryas Joel to exclusively serve its students with special needs.

One of the most outraged of the bill’s critics was Louis Grumet, a secular Jew who was then the executive director of the New York State School Boards Association. A “dyed-in-the-wool liberal for whom integration, separation of church and state and public education formed the holy trinity of his secular religion,” Grumet was shocked when then-governor Mario Cuomo said he would sign the bill—and responded by suing. Years of litigation ensued, ultimately reaching the US Supreme Court in the important 1994 church-state case of Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet.

Although the court found 6 to 3 in favor of Grumet, the opinions varied in their reasoning. Most notably, Justice David Souter, who wrote the plurality opinion, argued that the Kiryas Joel school district was an “unconstitutional fusion of religious and political authority.” But he was also sympathetic to the suggestion that the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause required that states only act neutrally toward religion. For Souter, the real problem with the New York statute was that it “singled out Kiryas Joel by name” for special treatment. This opened the door for the state legislature to rewrite the bill, which, after much wrangling and further litigation, it did. The Kiryas Joel school district exists to this day.

Stolzenberg and Myer’s central claim is that Kiryas Joel is “a quintessentially American phenomenon.” In a country founded on the principle of separation between church and state, the notion that a municipality could be effectively governed by religious law, and where non-Jews are not welcome, has not struck many previous observers as quintessentially American. Indeed, the 60 Minutes anchor Ed Bradley cast the Hasidic village as a threat to American values in an episode aired shortly before the 1994 Supreme Court case.

However, Stolzenberg and Myers argue that America’s twin commitments to the liberal principles of private property and religious liberty made the establishment of Kiryas Joel possible. The Satmars purchased legally available land in undeveloped areas of Orange County and created a private property association in which they invited their fellow Hasidim to settle. Only when confronted with the exclusionary zoning practices of the town of Monroe did the association transform itself into a municipal village, “an outcome that was neither intended nor desired by the Satmars at the outset.” Stolzenberg and Myers see this as an example of what they call “liberal illiberalism.” Even though Kiryas Joel rested on “a decidedly illiberal and hierarchical form of authority that prioritizes total obedience to the strict norms of the community over individual freedom,” it came into existence “as a result of the exercise of the most basic liberal right to private property.”

Moreover, Kiryas Joel bore little resemblance to its ostensible model, the historic shtetl of Eastern Europe. Shtetlekh were essentially little market towns that dotted the rural Eastern European landscape. Although Jews were typically a major segment of the shtetl population, they were not all Hasidim, and they generally lived among non-Jews. Teitelbaum’s original vision and the carefully curated reality Kiryas Joel were always more radically exclusive than this.

If Stolzenberg and Myers view Kiryas Joel as the paradoxical product of American libertarian ideals, they also acknowledge how changing political and cultural winds “contributed to the creation of a legal environment that was hospitable to the project of Kiryas Joel.” Christian conservatives eager to erode the separation between church and state supported Kiryas Joel, including in court. So, too, Stolzenberg and Myers claim (with less evidence), did multiculturalist critics of melting-pot assimilation, who rejected “a sameness model of equality” in favor of “a different model . . . that embraced cultural differences and their perpetuation as an ideal.” Both sides argued for a more robust communitarianism that would offer greater recognition of the collective rights of local communities.

Despite the outcome of the 1994 Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet case, the striking fact is that justices on both sides “gave voice to the value of accommodating group differences and allowing homogeneous communities to form separate enclaves and political institutions,” demonstrating the influence not only of communitarian thought, but—especially on the right—of an increasingly expansive definition of religious liberty.

As Stolzenberg and Myers show, most of the protagonists of the Grumet case—the lawyers and litigators, the judges, the government officials, the organizations submitting amicusbriefs—were Jewish and “represented the full spectrum of political and religious positions occupied by American Jews.”

Kiryas Joel itself was also rife with internal divisions. These were mostly rooted in a history of feuds over Satmar succession. When Reb Yoelish died in 1979, he left no heirs. He was succeeded by his nephew Moshe Teitelbaum, but from the start there were vehement critics of his rule, including the late rebbe’s wife, Faiga. Then, in 1999, Moshe split the Satmar empire between its two main branches, making his eldest son, Aaron, the chief rabbi of Kiryas Joel and his third son, Zalman Leib, the chief rabbi of Williamsburg. Neither son accepted the division, and, since Moshe Teitelbaum’s death in 2006, each regards himself as the sole Satmar rebbe.

The split fueled the emergence of another dissenting group in Kiryas Joel that repudiated Aaron and identified with his other brother Zalman, who was supported by Faiga, the continued nemesis of the Kiryas Joel official leadership. Both Moshe and Aaron responded by excommunicating the dissenters, prohibiting the sale of property to them, forbidding them access to the Kiryas Joel cemetery, barring their children from schools, and even turning a blind eye to violence against them.

Eventually, defying the traditional taboo on resorting to state courts, the dissenters sued. Ironically, of all its detractors, the dissident Satmars made the strongest constitutional argument against Kiryas Joel and its school district, citing its “blurring of religious and political power” as a clear violation of the Establishment Clause and characterizing Kiryas Joel as a theocracy. Ultimately, the parties settled, though both physical violence and litigation would resume in the 2000s. Since 2012, Stolzenberg and Myers maintain, the strife between the “disputing Satmar factions inside and outside [Kiryas Joel] has largely subsided.”

Stolzenberg and Myers contrast the Satmars’ tenacity in holding fast to their traditions and apart from outsiders with their pragmatic adaptability to changing circumstances, a perhaps paradoxical combination also singled out by Deutsch and Casper. Although the Satmars consciously shun “assimilation as a grave danger, even sin,” their very separatism, when viewed in the context of “patterns of American society . . . [that] are themselves increasingly separatist, or supportive of separatism,” illustrates what Stolzenberg and Myers call their “unwitting assimilation.” The Satmars have sought accommodation for their “seemingly foreign cultural ways,” yet they, too, have made accommodations to American ways to meet the legal challenges they have confronted. Through all the litigation, negotiation, and realpolitik that have marked the history of Kiryas Joel, the Satmars have acquired a “complete fluency in the language of American politics and democracy. They neither look nor act like traditional, cigar-chomping party bosses, nor do they physically or culturally resemble modern-day politicians. But they have learned the rules of the game and play by them as well as any.” Even the attempt to address the hardships of students with special needs—the very issue that provoked the main legal challenge to Kiryas Joel’s existence—coincided with the growing prominence of the disability rights movement in the 1970s and 1980s.

In a more troubling sign of “unwitting assimilation,” though it appears more strategic than involuntary, Stolzenberg and Myers point to a recent political realignment in Kiryas Joel. The Satmar Hasidim had traditionally been a voting bloc that swung between parties and candidates based on its interests. Yet in the two most recent presidential elections, Kiryas Joel’s vote for Donald Trump went from 55 percent in 2016 to 99 percent in 2020. Stolzenberg and Myers detect in this emphatic right turn a “hardening of Haredi identity in the mold of Christian conservatism with shades of white ‘Christian nationalism,’” adding that “the Satmars’ long-standing fear of assimilation has given way to assimilation into the present-day culture of right-wing libertarianism and antigovernment conservatism.” Perhaps, though the evidence for this, reliant as it is on the results of one presidential election (however arresting it may be), is still slim.

At a time when much of the recent popular literature on haredi enclaves has centered on those individuals who have left at great cost, these latest books strive to present a more rounded portrait of Satmar communities, whether in the “urban jungle” or in white suburbia, though they do not entirely avoid the darker sides of Hasidic life. Still, a sympathy for the Satmars, whether for their “urban sensibility and swagger” in the case of Deutsch and Casper or for their “steely resolve” and communitarian streak in the case of Stolzenberg and Myers, is palpable in both books and seems, at times, to come at the expense of a certain critical edge.

Deutsch and Casper deserve credit for enlarging the stereotypically secular, leftist, deracinated profile of the city Jew to include haredim like the Satmars. However, the latter seem to be more the exception that proves the rule—here, the irrefutable fact that far more Jews were moving out of than into New York in the postwar decades (including, ultimately, the Satmars)—than the basis for a substantial revision of the American Jewish story. Moreover, a widely discussed New York Times investigation last fall disclosed how most Hasidic schools in Brooklyn have utterly—and wittingly—failed to provide their students with an even half-decent secular education, all while collecting huge sums of government money because of their political clout. Such revelations highlight the social costs of savvy Satmar urbanites bilking the system, which Deutsch and Casper largely overlook. To be sure, the Times has long been accused, with some credibility, of an antireligious bias. But an article in the theoconservative magazine First Things was similarly unsparing in its criticism: “This isn’t about the culture war or the double-standards of the American left or how the New York Times has it in for the Jews (which it does). It’s about a community’s failure to raise literate Americans.”

While Stolzenberg and Myers do a masterly job of integrating Kiryas Joel into the main currents of American law, history, and politics, at times they seem to go too far in naturalizing it. One instance of this is their attempt to locate Kiryas Joel within the tradition of the American Jewish thinker Horace Kallen’s notion of “cultural pluralism,” which they define as “the view that group-based cultural difference is not antithetical to, but rather consistent with, classical liberal principles of equality and liberty and the idea of America itself.” Yet Kallen’s favorite metaphor for a pluralist society was a symphony, in which all the different ethnic groups, like instruments, have their “specific timbre and tonality,” forming a “multiplicity in unity.” In Kallen’s vision, the right to be different came with the obligation to participate in the great symphony of American life, not secede from it. He was also leery of any kind of tyranny of the group over the individual. To view Kiryas Joel, then, “as the fulfillment of the spirit of cultural pluralism” seems a stretch. Still, the gist of both books—that the Satmar enclaves of both Williamsburg and Kiryas Joel are not historical relics of the Old World but American born and made—is persuasive. The embeddedness of the Hasidim in the New York inner city has advanced to the point that, as Deutsch and Casper note, a classic 2004 Jay-Z music video uses “Hasidic visual references . . . to create a sense of ‘ghetto authenticity.’” They are less likely to become poster children for life outside the city, but nearly fifty years into the experiment of creating Kiryas Joel in the suburban periphery of New York, they are no less rooted there than in Williamsburg.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Early Modern Mingling

How the Jews became modern.

Wild Things: The New Neo-Hasidism and Modern Orthodoxy

Who are Joey Rosenfeld and his pseudo-Hasidic pranksters, and what does their success have to do with the future of Modern Orthodoxy?

Succession, Secession!

The notion of zera kodesh, “holy seed,” appears only twice in the Bible, both times in reference to the people of Israel as a whole. For Hasidim, however, it has a more restricted meaning.

My Scandalous Rejection of Unorthodox

All of us in the online OTD community have gone through some version of the transformation Unorthodox dramatizes, and we gobble down and fiercely debate every new OTD memoir that hits the shelves, every documentary and movie that comes out.

Harold Males

The rivalry between the two brothers had many positive ramifications for the non-Hasidic Jewish world. Each camp tried to outdo the other in providing services to the in-group: more and better-appointed mikvos and shtibelach. A relative of mine was able to unload a small oddly shaped lot that bordered a site purchased by a Satmar faction. In addition a Satmar group from Monsey bought the old (Rabbinical Seminary of America) Chofetz Chaim Yeshivah building (and built a mikveh in it) allowing for the building and furnishing of thie new (Sy Symms) buildng. Satmar even bought a disused school building, renamed it Ateret Cohanim and installed a money-making wedding hall. But before that they took care of the most obvious need -- a cut-in at the curb to allow buses to pull in and not obstruct traffic. I suspect that all the building was done without pulling the proper permits--but who really cares, right?