Bookstore or Beis Medresh

A student recently came up to me to ask how she could become “someone who knows things.” Browse, I said.

My own browsing education began close by, in good bookstores near my Upper East Side Jewish high school where I now also teach. During free periods, after school, or whenever I thought it best to take my education into my own hands, I headed to Books and Company. I remember buying a book by Leo Strauss about ancient and modern liberalism—but why? It must have been for the opening essay “What Is Liberal Education?” since I wouldn’t yet have cared about how to begin studying The Guide of the Perplexed and “Marsilius of Padua” meant nothing to me as an adolescent yeshiva bochur. I didn’t get to those chapters until quite a bit later. Others still wait.

When helping my father at his office in the Diamond District, I would sometimes steal away to the Gotham Book Mart to browse poetry with a parcel of carat stones in my pocket. I’d proceed from spine to spine, mentally sorting between names I half-recognized and those I had never heard of: Baraka, Baudelaire, Bishop, Blake, Browning, Bukowski, Byron. In the East Village, I would go with my uncle whenever he was in town to St. Mark’s Bookshop, which he had managed in the 1970s. My uncle would chat with his old bookseller colleagues while I scoured the shelves.

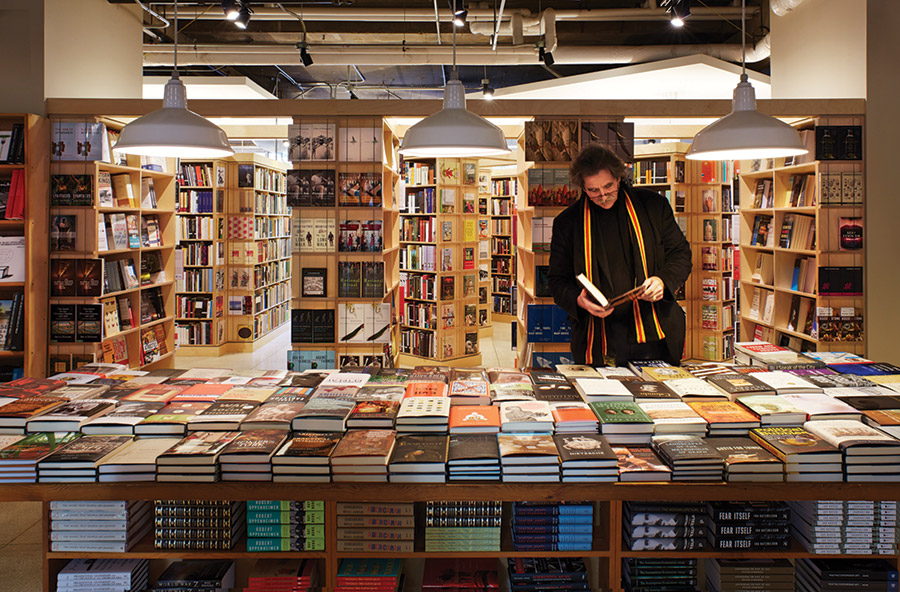

But things really took off when I got to college, with my first descent into Chicago’s Seminary Co-op Bookstore. The untreated pine shelves in the store’s cavernous original location were crammed with books from floor to ceiling: philosophy and theology toward the back; linguistics and Marxism flanking the doorway to a side room that housed poetry, anthropology, and African American studies; art history covering a wall in the central room that also contained the famed Front Table of recent scholarly releases. Now this was a bookstore! I bought my shares to become the co-op’s 47,324th member.

I don’t know how many hours I spent among these shelves, but it was more than I spent in class and certainly more than I spent reading books from cover to cover. Am I alone in this among bibliophiles? I doubt it. There’s a practical value to browsing over reading. It gives you the lay of the land. While there are whole schools of thought I may never give their due, I’m better off knowing that they are out there. Yes, we might “read to know that we are not alone,” that there are others like us, as the C. S. Lewis character in Shadowlands claims, but browsing in a good bookstore serves to remind us that there are also serious minds who differ. I told my student to browse because becoming “someone who knows things” begins with struggling against the safety of home.

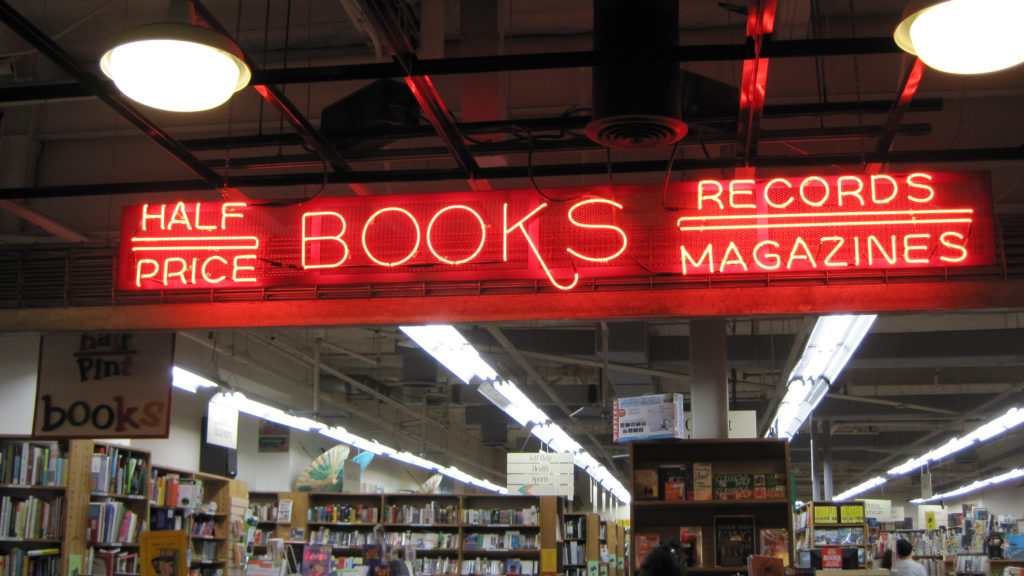

Jeff Deutsch, who has been managing the Seminary Co-op since 2013, knows that bookselling itself cannot justify the existence of a good bookstore. Amazon has sent many favorites into extinction, including the New York bookstores of my adolescence. Deutsch resists providing yet another lamentation over their demise, insisting rather that we must “imagine a future in which bookstores not only endure but realize their highest aspirations.” His manifesto celebrates browsing as essential to the thinking life.

In one of the book’s most charming moments, Deutsch offers a typology of the different kinds of browsers he’s observed over years of bookselling:

A non-exhaustive list of those we see in our wilds would include the flaneur, who meanders through the stacks, observing, loitering, shuffling; the sandpiper, who sees the world in a grain of sand; the town crier, who heralds the latest news from the pages of the books on the front table; the ruminator, chewing their cud; the pilgrim, seeking wisdom, they know not what or where, but knowing that they must find it; the devotee, who prays daily, regardless of the season; the penitent, who has not lived as they ought and is now seeking redemption, or at least forgiveness; the palimpsest, who reads and rereads and knows that every reading leaves its inscrutable mark; the chef, who trusts their senses to help them identify the most delectable ingredients; the initiate, who doesn’t know the mores of the place but is hopeful they might soon belong; the stargazer, who takes in the sky with a well-honed attention; the general, who sees the stacks as a thing to be conquered; and the idler, who just wants to while away the hours among books.

As Deutsch’s list suggests, there isn’t one right way to inhabit a good bookstore. (I’m mostly a general, with pilgrim and chef tendencies.) Set these different browsers free in a well-stocked bookstore, factor in the planned juxtaposition of different sections and the unplanned elements that influence a browser’s path—an enticingly colorful cover, the obstacle of other browsers, barometric pressure—and the possibilities of “who we might become” approach infinity. The good bookstore Deutsch imagines contains multitudes.

Multitudes, but not everything. “If we are to understand the art of bookselling and the practice of the bookseller,” Deutsch writes, “we must first understand the discernment and arrangement required in crafting a good bookstore.” A good bookstore cannot carry all books, nor should it. Deutsch defines the work of a good bookseller as “filtration, selection, assemblage, and enthusiasm.”

The relationship between browser and bookseller rests on trust.I must trust the bookseller to have weeded enough that any book I pick up “is worthy of, and will repay, close attention” but not so much as to eliminate competing points of view. A good bookseller must, in turn, trust me to be responsible for my own education.

Put another way, a good bookstore is agnostic about the good. I might have spent my college years browsing Brecht and Benjamin rather than Becker and Friedman, but they were always available to me a few shelves away (and, eventually, I found them too). The greatest thinkers have disagreed about the most important matters. A good bookstore provides an initiation into those controversies without taking sides. It provides a space where it’s okay to be uncertain. Where one might even take pride in one’s indecision.

Of course, not all bookstores with excellent collections are good in this sense. Some of my favorite bookstores aren’t agnostic at all. There are thematic bookstores like The Drama Book Shop and Kitchen Arts & Letters, which assume a shared passion for their chosen subject areas. They clearly consider theater and cooking to be good—but only a fanatic would take these to be the good in an Aristotelian sense. Bookstores like Bluestockings Cooperative in downtown Manhattan and Z. Berman Books in Brooklyn are motivated by a more totalizing vision of the good: smashing the patriarchy, a life of Torah and mitzvot. These are activist bookstores. When I walk into such stores, I always suspect that the staff and other patrons can see through me—that I’m not a fellow traveler, that I’m not on the derekh. At the Seminary Co-op, it’s different.I’m presented with the options but left to decide for myself.

But Deutsch wants to take bookstores even further:

Acknowledging that the books themselves are often at war with one another, arguing stridently, in the strongest of language and with the highest of stakes about truth and consequences, there remains something restorative about the bookstore itself.

For Deutsch, the bookstore of perpetual debate re-creates the beis medresh of his youth. His praise of good bookstores is inseparable from the personal story of being a boy raised in “an Orthodox Jewish community in and around Brooklyn” who first descended into the Seminary Co-op as a teenager attempting to take his leave from a religion predicated upon books. “To a confused and restless young man trying to find his way in the world,” Deutsch confesses, “the Co-op seemed as close to a spiritual home as he could hope to find.”

That was in 1994, two years before my own first descent into the Seminary Co-op, where I, too, felt a sense of discovering home. And yet I resist equating the ideal bookstore with a beis medresh, no matter how heterodox. Machiavelli might “sound like a talmid chacham” in his famed letter to Vettori, but let’s not mistake him for a student at the Mir. While the Jewish canon can be admirably expansive, it remains predicated on a communal agreement that a good bookstore neither can nor should command. Deutsch writes of “legion secular talmidim” building their “own private Talmud” from the shelves of a good bookstore. Though there is something noble in this image, a private Talmud remains a contradiction in terms.

Deutsch admits to being “seduced by the heresy of intellectual heterodoxy.” Fair enough. There is wisdom in the tents of Japhet as well as Shem, and we ignore it at our peril. But Deutsch doesn’t leave things there. Like the messianic mystics of old, he wants to claim redemptive force for his apikorsut. He envisions a new community emerging “where everyone is their own rebbe.” Deutsch is right to emphasize a connection between good bookstores and strong communities, but it takes a certain American Jewish chutzpah to enlist Midwest bookstore goers as fellow apostates in one’s quest for tikkun olam. The Yiddishkeit here verges on narishkeit.

In 2019, Deutsch oversaw the Seminary Co-op’s transition into the first not-for-profit corporation whose mission is bookselling. The store’s website now includes a page where donors can make gifts “to invest in the browsing experience.” These gifts are not tax deductible since the IRS has yet to recognize browsing as a charitable cause. “Rather than attempt to shift our mission to fit ourselves into the IRS’s set categories of qualifying causes,” the website declares, “we are adamant that bookselling itself is a cultural good.” Deutsch’s book provides little detail on how the store has fared under its new economic model. He does, however, suggest where he found inspiration for the idea:

The contemporary kollel, by acknowledging that the financial support of scholars studying Torah is a means by which those who are consumed by their daily work can help lift up the community, has found an elegant solution to the question of value and worth. . . . The descendants of Rabbi Judah bar Ilai understand that not everyone is created with the same appetite or facility for study. They see wisdom in a model whereby some community members make their daily work their regular concern so that other community members might make the study of Torah their regular work. In this way, the entire community is sanctified by Torah study.

Deutsch wants to build a community that is sanctified by browsing. But for the kollel analogy to hold, the bookstore would have to attract donations from those without an appetite to browse. They’d need to believe that browsing is a communal good even if they don’t personally have a taste for it. Though I have every hope that the not-for-profit model will serve the co-op well, I’m skeptical that it can sanctify American society by means of a new partnership between those who work and those who browse.

Besides, is sanctification really what America needs? Couldn’t we, in fact, do with a little less self-righteousness? In its better, more moderate moments, In Praise of Good Bookstores clearly articulates the positive contribution good bookstores can make. Browsing in “spaces that will challenge, not just echo, our assumptions, is an act of citizenship as much as its own individual reward.”

Rather than confirm us in our beliefs—as both activist bookshops and algorithmically determined “Books You May Like” suggestions tend to do—a good bookstore provides a space in which to throw things into question. Good bookstores don’t bring redemption; they help us live together without it. By keeping the Seminary Co-op’s doors open and its shelves well stocked, Deutsch contributes daily to this essential work.

Before taking my current job, I spent three years teaching at a liberal arts college in Berlin. Among its swag was a mug with a quote from Hannah Arendt: “There are no dangerous thoughts; thinking itself is dangerous.” It was the kind of item many bookstores have taken to selling on the side to make ends meet. Still, Arendt had a point.

As a space to inspire thinking, a good bookstore is fundamentally unsafe. Or, at least, risky. Like the pardes of rabbinic myth, you never know how those who enter will emerge.

Suggested Reading

Trilling, Babel, and the Rabbis

Part of Trilling's mystique came from the way he seemed "to be a Jew and yet not Jewish."

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

Books on the Cheap

After the bookseller had read something from a random page, he suddenly exclaimed, almost in panic and in as broad a Texan accent as I had ever heard, “Wait a minute. I know what this is. I’m not going to sell this! Get this out of my store. Take it. Get this out of my store!”

Watching Game of Thrones, Waiting for Shavuot

Binge-watching the traditionless Game of Thrones while looking forward to the traditional binge-learning of Shavuot.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In