Books on the Cheap

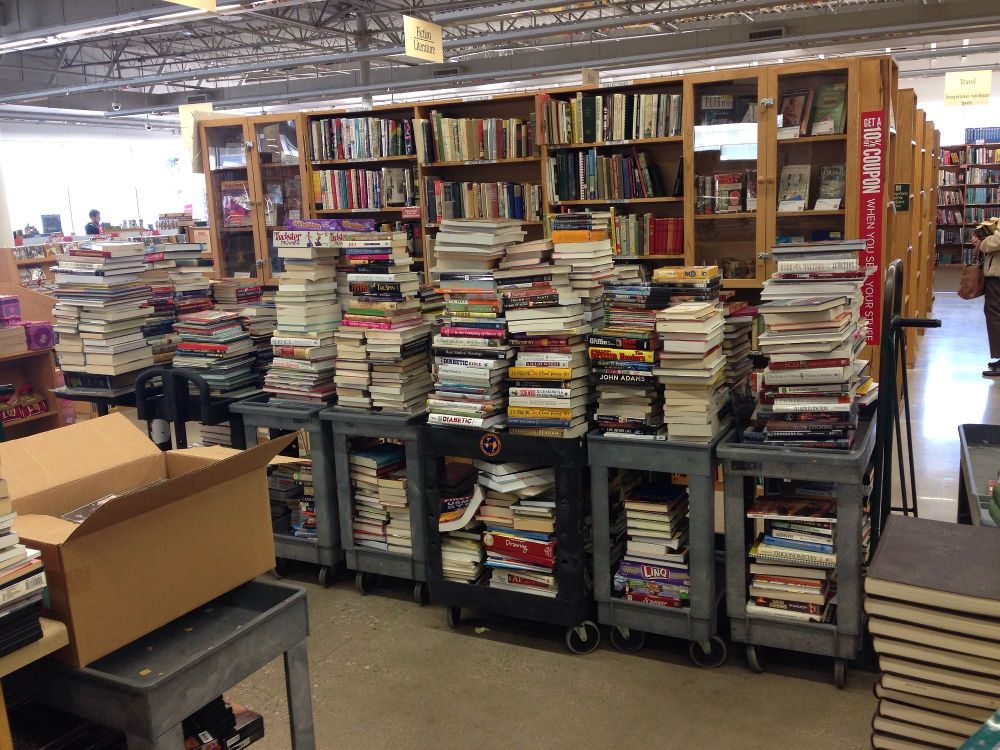

I have spent too much of my life in used bookstores. But I probably wasted more time in them during the two academic years in the mid-1980s that I was teaching in Dallas, Texas, than I have before or after that. There was so little else to do there, and there were so many branches of Half Price Books, from the huge, flagship store near Southern Methodist University to the far-flung, much smaller, but still enticing outlets in Richardson (where I resided), Irving, and other largely indistinguishable suburbs that made up the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex.

I only checked out the store in Irving on my way to or from the Dallas-Fort Worth airport, but it was there that I made one of my more memorable acquisitions. Browsing in the religion section, I found a decades-old copy of Henry Ford’s anti-Semitic screed, The International Jew. Of course I knew about it, but I’d never actually seen a copy before and was pretty sure that I’d buy it whatever it cost—but it didn’t have a price penciled on the inside of the front cover. So, I brought it to the guy at the register to find out what the store would ask for it. He took the book, looked inside and found no indication, and then he started leafing through it. After he had read something from a random page, he suddenly exclaimed, almost in panic and in as broad a Texan accent as I had ever heard, “Wait a minute. I know what this is. I’m not going to sell this! Get this out of my store. Just take it. Get this out of my store!”

I never felt more blessed to be an American.

Around the same time, I went to a book sale at the Dallas Public Library. Among the bargains I found there was a copy of the only recently published The Redemption of the Unwanted: From the Liberation of the Death Camps to the Founding of Israel by the founding president of Brandeis University, Abram L. Sachar. As I waited in the line to pay, I had no trouble identifying the volunteer cashier as what people in Dallas then called a “transplant.” In fact, from his accent, I could tell that he grew up not far from the neighborhood in Brooklyn where my father had learned English as a small boy. And from the look of him, I was sure he was Jewish.

He chatted a lot with all the customers, but I can only remember what he said when he looked at one of the books the man just ahead of me in line wanted to purchase. “Bawn Again. Bawn again? Whaddya wannabe bawn again faw?” That was apparently the question this customer lived to be asked, and he eagerly began to explain why. But the transplant wasn’t buying: “Once is enough,” he said. “Once is enough!” He took the man’s money and then turned to the small stack I had placed on the desk in front of him, with Sachar’s book on top. “The redemption of the unwanted,” he uttered, slowly and thoughtfully. When he turned the inside cover to see what to charge me he saw what I had seen: listed at $19, the book was selling for $2. Then he looked me in the face, winked, and said, “Faw you, one dollah.”

I have relished the memory of this little Jewish conspiracy against the Dallas Public Library for more than 30 years now, but it wasn’t until a couple of months ago that I actually read the book at the center of it. A colleague asked a bunch of other professors on a Listserv for recommendations for books on the relationship of the Holocaust to the creation of the State of Israel. Someone whose judgment I respect recommended The Redemption of the Unwanted. I guess it’s time, I thought, and took the book down from the shelf where it had rested, untouched, for a very long time.

I’ve read it now, and I have to say that I don’t think I missed much by waiting three decades to get around to it, but I don’t say that disparagingly. It’s a very good book, even though it doesn’t contain much that I didn’t already know. Its chief merit is that it does an exceptionally good job of teaching a very important lesson.

Most people in the United States, I’m afraid, if they know anything at all about how the State of Israel came into being, believe that after World War II the nations of the world awarded it to the Jewish people as a compensation for what they had suffered at the hands of the Nazis. There’s a grain of truth in this, but only a grain. Between 1945 and 1949, the Zionists had to do a tremendous amount on their own in order to obtain a state. They engaged in a vast amount of worldwide politicking, organized illegal immigration into Palestine, and fought the British administration there, both to earn the world’s sympathy and to force the British government’s hand. Had the Zionists not done all of this, there would have been no decision at the United Nations to partition Palestine and create a Jewish state. And had the Jews of Palestine then sat on their hands and waited for the UN to implement its decision, that state would never have come into being. They had to fight, basically by themseleves, a war of independence against the Arabs of Palestine, as well as all of the surrounding nations. And they won that war, Sachar reminds us, largely because they were imbued with a “‘no alternative’ (ain breira) spirit.” They knew “that the land they defended represented a last hope for them” and that if the battle “were lost there would be no heart left to continue the struggle, either for them or for the survivors of the Holocaust remaining in the camps and transit points of Europe, Africa, and Asia.”

Abram Sachar was by no means the first or the last to explain all of this, but he did a singularly good job of it. Writing in a clear style, with controlled passion, and a broad knowledge of all aspects of this period of history, he packed into one reasonably short volume just about everything one ought to know about the subject.

If I were reviewing it now, I might quibble with his decision to devote so much space to President Truman’s Jewish adviser David Niles at the expense of so many other important figures on the American scene to whom he gives relatively short shrift (Sachar was the executor of Niles’s estate, and he had once planned to write an entire book about him). But no book is perfect. I only regret that I didn’t read it earlier, so I could have recommended it to others all these years. You can buy it on Amazon for $4.98.

Suggested Reading

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

Twilight of the Anti-Semites

Nietzsche’s reception has been sharply divided between anti-Semitic and philo-Semitic readings. Richard C. Holub's new book explores how the philosopher's views changed over time and whether some of his statements about Jews should be attributed to another hand.

Chaos in the Wilderness

Unlike reporters who are happy to rework official government statements, Mohannad Sabry reports on the Sinai by drawing on a broad network of sources in the region.

The Kibbutz and the State

How the position of the kibbutz in Israeli society has changed, and why.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In