Those Days Are Gone Forever

What’s the matter with kids today? It’s at this point in the song that I’m transported. On a rec hall stage, on the far side of camp from the chader ochel, the dining hall, a troupe of older campers perform the 1960 musical Bye Bye Birdie. I don’t remember much besides that line and the laughter it sent rolling through me. Here were kids, pretending to be parents, complaining about kids to a kid-filled audience—and we lapped it up. The layers of irony simply sent me. It was another strange and thrilling moment in a summer of fun at a Reform camp in the mid-2000s.

Fun only gets you so far. That summer or the one after was my last at overnight camp. The bullies were awful and I never really fit in, but I sealed my own fate when I got into a brawl with my camp best friend and socked him in the nose. How were you supposed to go back after that? The summer after high school, though, I signed on as a counselor at the Modern Orthodox camp where all my friends went. I learned quickly I had little talent for working with kids. Worse, my cocounselor and I were both newbies—we didn’t know a thing about this camp and its traditions. Our bunk ran roughshod over us.

Sandra Fox’s accessible and comprehensive new history, The Jews of Summer, shows, among many other things, how a midcentury Broadway musical fits snugly into the structure and ideology of Jewish summer camp. It also leaves the unflattering aspects of camp—bullying, kids of varying competence taking care of other kids, and brawls among them—mostly untouched. Nonetheless, The Jews of Summer presents a rich historical narrative largely gleaned from camp archives and alumni interviews. Almost as rich is the vein of nostalgia running through it.

Leaving aside for now the problem of nostalgia, there is much to admire in the book. Not the least of its strengths is a compelling, multigenerational narrative about the importance of summer camp in postwar Jewish culture, an age of abundance that lasted from the 1940s until the mid-1970s. Jewish camping dates back to the turn of the twentieth century, when “fresh air reformers” in Europe and America invented summer camp to combat the apparently baleful effects of city living—but campers like me ended up at camp, according to Fox, because of what it became in the postwar decades. The Jewish educational summer camp experience that emerged from that time struck parents and experts, communities and institutions as something that worked. A consensus developed over the decades, which was eventually confirmed by social scientific research, “that Jewish camps largely succeed in their goals in transforming young Jews.” Indeed, studies show that camp alumni are more likely to marry Jewish, stay in the community, and feel connected. Outside the overlapping worlds of Orthodoxy and day school, there is hardly anything else with that effect.

The irony is that the camping experience in the age of abundance largely grew out of disapproval of mainstream American Jewry and dissatisfaction with its ways. Building on the research of historian Rachel Kranson, Fox points out that leading midcentury Jewish figures worried that “authentic Jewish life” was “incompatible” with suburban prosperity and lowered barriers to Jewish assimilation. The memory of the Holocaust compounded the feeling that American comfort was disreputable, even immoral. Like the fresh air reformers before them, camp founders and leaders wanted to protect children from the long-term dangers of their environment. In this case, however, the principal danger was a loss of Jewish character.

When the counterculture came of age in the 1960s, the Jewish critique of affluence meshed easily, almost imperceptibly, with the broader critique of bourgeois values. Camp leaders, including energized young staff, recognized the continuity between one critique and the other and aimed to capitalize on it. Although the younger generation was inspired less by fears of suburban comfort than by the counterculture and a newly vibrant politics of identity, similar critiques of American Jewry shaped the mission of educational summer camps throughout the postwar era. In fact, this continuity of purpose from the late 1940s through 1970s and beyond is the engine that drives Fox’s narrative.

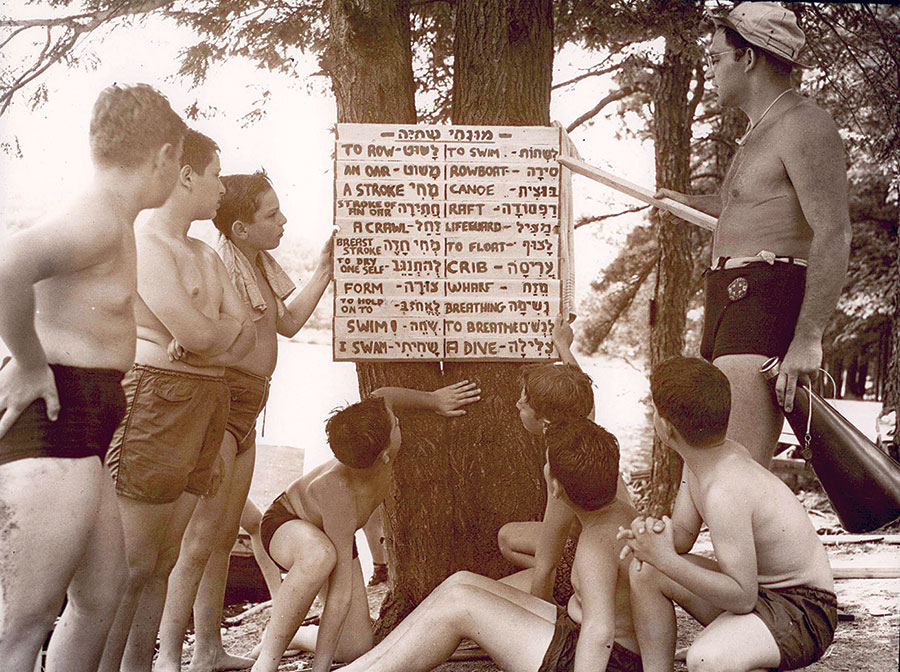

Fox adroitly covers the whole history of American Jewish camp, from its rise at the turn of the century to the recent pandemic. She considers how time, play, romance, youth culture, Jewish languages, and Holocaust memorialization in camps structured the experience of the three largest streams of Jewish educational camping—Reform, Conservative, and Zionist—and a minor but notable variation—Yiddish camps. In each chapter, Fox shows how these elements were crafted to inculcate an ideology of authentic Jewishness in campers. In doing so, she draws on a wide range of material, including oral histories, personal interviews, camp newspapers, and staff documents. She uncovers some important trends, such as the use of the Holocaust in camp education, but she also sometimes overgeneralizes from her sources.

In late July 1944, campers at a Habonim (Zionist) camp dressed themselves in white, entered a cafeteria stripped of chairs and tables, and sat on the floor and listened to a reading of Lamentations, in observation of the fast day of Tisha b’Av. Yahrzeit candles were lit in the center of the cafeteria, where a counselor stood and described the horrors of a concentration camp. A year before the end of the war, the Holocaust had already seared Jewish consciousness. This snapshot of Holocaust memorialization hints at a wider process underway: the linking of the Holocaust to Tisha b’Av in all but the most secular Yiddish camps. In addition to being another refutation of the post-Holocaust silence thesis, this link exemplifies how the Holocaust became a means of instilling Jewish character in campers. For the Habonim camp staff, Tisha b’Av and the Holocaust served to remind their charges why a homeland matters.

Another example of the educational use to which the Holocaust was put comes from the secular Camp Hemshekh’s Ghetto Day:

While campers already knew before the day that “at its best, Hemshekh is a mainstay of Yiddishkayt’s survival today,” the counselors complained that they littered the campgrounds and went to great lengths to avoid attending Yiddish class. . . . After Ghetto Day, however, campers reportedly headed to Yiddish class happily. One counselor suggested that the camp should schedule Ghetto Day toward the beginning of the summer . . . because then the staff could remind them “for the next seven weeks, ‘But you cried on ghetto night, didn’t you?’”

Put bluntly, staff used the Holocaust to guilt campers into enthusiasm for Yiddish.

Yiddish camps were by no means the exception. Every camp in The Jews of Summer “employed the camping idea in strikingly similar ways,” to shape authentic Jews in a time of abundance-fueled cultural decline, however that authenticity was defined. Fox shares the fascinating observation of Rabbi Donald Splansky that Tisha b’Av, hardly touched on in synagogues, “would have likely disappeared from the Reform movement” without the generations of campers who experienced it in camp and found meaning in the day.

It matters tremendously to Fox that campers resisted their camps’ various missions (for example, by avoiding Yiddish class) and that they influenced the very movements that aimed to mold them, as the preservation of Tisha b’Av in the Reform movement suggests. In fact, these dynamics point to the book’s overarching theoretical argument—and the source, as I intimated, of a lamentable, if inadvertent, nostalgia for its subject matter. Fox’s goal in The Jews of Summer is to tell a bottom-up social history of Jewish summer camp. Instead of telling us what educators and ideologues thought about camp, the book works to present “the myriad ways that young people shaped camp life”:

Because camps’ abilities to succeed educationally and economically fundamentally required the buy-in of campers, children and teenagers wielded tremendous power within the camp environment in their everyday reactions, their decisions to engage or disengage, to nod in agreement or roll an eye in defiance. . . . Campers and young counselors . . . influenced the very ideologies camp leaders came to highlight.

Moments like a perhaps satirical demand by teens at Camp Swig to be allowed to swear on Shabbat shine forth for Fox as signs of the “intergenerational negotiation and nuanced exchanges between youth and adults” that define the real dynamics at camp.

Too often, Fox’s approach turns quotidian behavior into acts of ideological rebellion, often with unconvincing results. The chapter on Jewish languages, as you might expect, is full of kids griping about the language learning that their counselors believe will transform them into proud, self-assured Jews. Fox tells us that at Conservative Camp Ramah, despite efforts to create a Hebraist environment, “campers continued to resist the idea of speaking Hebrew among themselves.” Yet this statement comes after we learn that Ramah struggled to recruit campers with the Hebrew skills desired by staff. Maybe these campers didn’t want to speak Hebrew among themselves, but isn’t the key factor that they couldn’t?

Similarly, much is made of the decline of spoken Yiddish at Yiddish camps. One Hemshekh alum told Fox that in the late 60s, “campers complained about . . . the Yiddish educational program, finding it dull.” This apparent threat to the fabric of Yiddishism at camp actually came from the administration before it arose among the campers. Mikhl Baran, camp director, recruited non-Yiddish-speaking campers from the wealthy Long Island suburbs where he taught, hoping to increase the camp’s financial base. Complaints about Yiddish learning were a byproduct of a savvy, top-down economic decision.

Finally, when we do see legitimate grassroots resistance to language instruction, it seems as likely to come in the form of bullying other campers as rebellion against authority. Again at Ramah, campers who did speak Hebrew in the 1950s shied away from doing so too conspicuously “lest they become known as ‘queers’ or ‘apple-polishers.’”

Ironically, many of Fox’s cutting observations about the mismatch between Ramah’s Hebraist aspirations and its English reality come not from campers but a visiting writer in the 50s named Morris Freedman, who wrote a skeptical article about the camp’s Hebraism. At one point, Fox tells us that Freedman was told by a camper that she didn’t much understand the Hebrew announcements that she’d just been “attentively listening to,” a comic instance of expectations overshooting abilities. Quoting an article replete with zingers about the caprices of American Hebraism isn’t necessarily a problem, but it isn’t quite what one imagines when Fox says hers is a story of summer camp from the campers’ perspectives.

Each of the central chapters of The Jews of Summer provides another angle on resistance to official camp ideology, some of which are more convincing than others. The problem isn’t with any one example or set of examples; it is a methodological issue. The issue is nostalgia.

To an extent, Fox is right to get away from official narratives. There is only so much one can learn about the lived experience of summer camp from memos and letters, statements of vision, and financial documents from founders, directors, and staff. Certainly, these will contain descriptions of camp as its architects would like it to have been, rather than as it was, though Fox makes excellent use of camper disciplinary reports to reveal precisely what sort of attitudes they tried to stamp out. Still, “the book’s detailing of camp life is derived chiefly from archival research” into documents that the camp administrators decided to preserve. This is why her other key source is so important. Fox writes:

As I observed and became an occasional participant in alumni Facebook groups over the course of several years, I also had the pleasure of connecting with dozens of former campers . . . who generously donated helpful sources, photographs, and memoir literature they wrote of their time at camp. I conducted over thirty in-depth oral history interviews with former campers.

Alumni offer the granular, untidied versions of camp not so readily available in official archives. Or, I should say, they offer another version of camp. As Fox indicates, her archive of personal material and pool of interviewees is drawn, at least in part, from connections made in alumni Facebook groups. To say the least, this is a sample with a bias. Those who create, join, maintain, and participate in such groups, decades after their time as campers, are also those most likely to look back fondly on their summer experiences.

Perhaps this is why the book contains so few of the unflattering aspects of camp. Again, there is little here about bullying, incompetence, and brawls, not to mention petty hierarchy and intragroup division, all of which must have had an enormous impact on campers, if Jewish summer camp isn’t to defy our accumulated anthropological and psychological knowledge of the dynamics of social life. If that smacks of generalization, consider what the great sociologist Erving Goffman had to say about the total institutions, such as prisons, asylums, and monasteries, to which Fox likens camp. Goffman described a world marked by intragroup abuse and fleeting solidarities. “Staff or fellow inmates call the individual obscene names, curse him, point out his negative attributes, tease him, or talk about him or his fellow inmates as if he were not present.” In the most extreme environments, “the inmate cannot rely on his fellows, who may steal from him, assault him, and squeal on him.” Summer camp is obviously not a prison or a mental hospital, but Fox is not wrong to regard it as a total institution in which peers live together in an administered environment cut off from their ordinary lives. That is, of course, what makes it a special place. The point is that a dimension of camp social life we can reasonably expect to exist—and to be powerfully, sometimes painfully experienced by adolescents—finds no significant treatment in a book about camp experience.

None of this invalidates the broad and instructive historical narrative of The Jews of Summer. It does call into question Fox’s claim to eschew nostalgia. Indeed, anyone who went to Jewish camp will notice another thing that Fox doesn’t say: kids who are deeply influenced by their camp experiences are the most ideologically constituted creatures one can imagine. While the power of rolled adolescent eyes must be readily acknowledged (as a former counselor, I have felt their withering effect), some of the main arbiters of camp experience are the campers who embody the camp’s spirit. They can’t be sycophants, but neither can they stray too far from the ideological bounds of camp culture. The great success of Jewish camps has been precisely that they have succeeded in making one or another version of Judaism and Jewish identity cool for their campers.

In The Jews of Summer,Fox wants to show how ideologies of authentic Jewishness are contested and redirected by campers, but many of the stories she tells indicate that the campers’ more typical response is to absorb and reflect them. Sometimes it seems as if Fox pictures Jewish summer camp as a time of free-wheeling, ideological contestation, like something out of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, where the shibboleth of the sanatorium (another total institution) is placet experiri—“it is pleasing to experiment.” Yet, sometimes the camp experience shares at least as much with Lord of the Flies, in which power and following are won by those who wield the accoutrements and ideology of authority. It is hard not to see an overlay of nostalgia shared by Fox (a camp alumna herself) and her principal subjects as part of what prevents these all from being mentioned, let alone systematically addressed.

Fox’s title, The Jews of Summer, is, of course, an ironic play on “The Boys of Summer,” a Don Henley song (“I can tell you, my love for you will still be strong / After the boys of summer have gone”) and Roger Kahn’s famous 1972 book about the Brooklyn Dodgers, both notably steeped in golden-hued memories of summer. As a historian, Fox explicitly rejects such “comfortable nostalgia for simpler summers past.” However, when I closed the book and saw the title again, I was less sure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

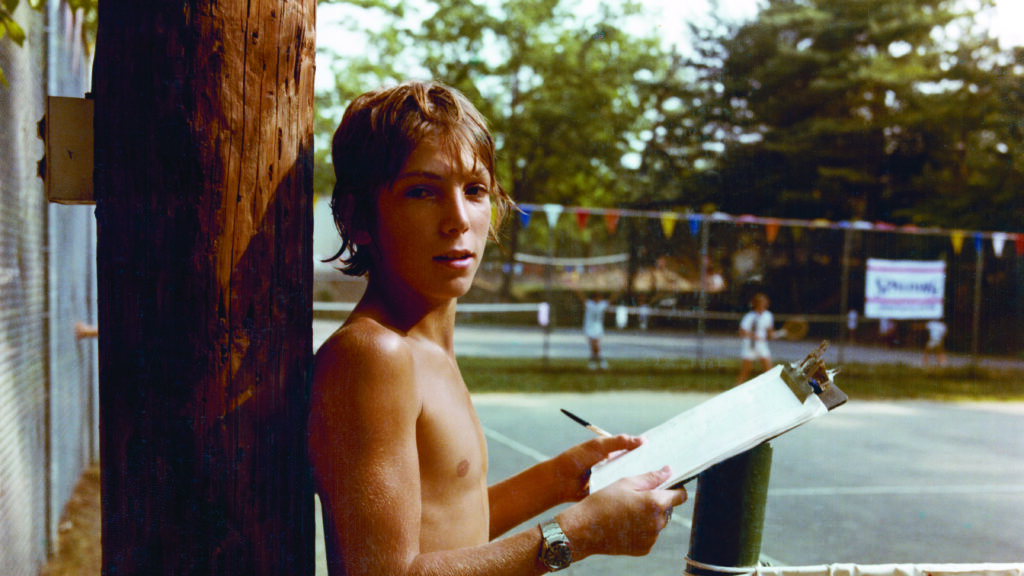

Camp Mountain Lake, 1977

The picture-taking began when he was still a little kid, at Camp Mountain Lake in North Carolina. The owners of the camp remember a chubby kid, not very athletic, and the camera was a way of making friends.

Revisiting Herman Wouk’s City Boy

Remembering Herman Wouk's "gentle mockery at the shopworn pretensions of bohemian poseurs and ethnic Jews passing as nonhyphenated Americans."

Yiddish Genius in America

The great Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein wrote two autobiographical novels and envisioned a third, set in America. Why didn’t he write it?

Our Master, May He Live

Rashi's commentary on the Chumash isn't just about textual puzzles, it's about God's love for the Jewish people. So argues Avraham Grossman in a new biography.

Samuel

As another graduate of Jewish camps, I too remember bullying and fighting, although it isn't like that is absent from other environments that children inhabit, nor is it absent from non-Jewish camps. Unfortunately, a lot of the bullying was directed at children who were non-conforming in gender or sexuality, which is something I believe would be less prevalent today.

Yeshua G. B. Tolle criticizes Sandra Fox's book for falling into nostalgia, but I don't think nostalgia is necessarily historically wrong or irrational. The post-War decades were a kind of Jewish Golden Age, where Jews had more opportunities open to them than previously in the United States (or at any time in Jewish history), yet Jewish cohesion and knowledge was stronger than at the present. It was a time when kids at Yiddish camps (who were fortunate to have grandparents), probably had 1-4 grandparents or even parents who knew Yiddish. It was a time before many Jewish Americans began to feel conflicted about Israel. It was also a time when Jewish kids would not have learned about the Shoah from their regular school, so learning about it at camp filled in what would otherwise be a gap in their educations.

I also think nostalgia for childhood is normal. Childhood is a time of innocence and joy. Camps, even when they have ideological and educational projects, are also meant to be places where kids have fun and form friendships. For adults to look back at the good parts of summer camp and not dwell on the bad parts, isn't irrational. It's psychologically healthy.

I'm a graduate of Jewish summer camps and now a Jewish summer camp parent too. Yes, I hope my children learn more about Jews and Judaism at camp, even if a critic would call it "indoctrination." Yes, I hope they learn songs they will remember and learn their prayers better. Yes, I hope they form friendships. If there are bad things, I hope they can learn to emotionally overcome them.

And decades from now, when they are middle age and then old, I hope they have their own nostalgia.