Our Master, May He Live

I spent the summer after high school in the Poconos with a group of other recent graduates learning how to become a Camp Ramah counselor. One of our teachers was a remarkable young Israeli, a Jewish type none of us had yet encountered. He had a long, squared-off black beard, a high forehead crowned with a knitted kippa, khaki shorts, and army boots. He taught us “Chumash with Rashi,” effortlessly leafing through his well-thumbed Hebrew Pentateuch with the medieval commentators. Whether we understood it or not, he was making the case that Rashi was not just solving problems of biblical interpretation, he was also arguing that God’s love for the Jewish people was the main point of the Bible. For our teacher, Dov Rappel, who went on to a distinguished intellectual career in Israel, this was as true nowadays as when Rashi wrote it.

Jewish biographies are everywhere, but few if any subjects can lay claim to the importance of Rabbi Shlomo b. Isaac (1040–1105), commonly known by the acronym Rashi (on which, more later). Avraham Grossman, a distinguished medieval Jewish historian, professor emeritus at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and winner of the prestigious Israel Prize, is arguably the most learned scholar today writing about the life and works of Rashi. This biography originally appeared in Hebrew in a series produced by The Zalman Shazar Center, whose other subjects include classical figures such as 10th-century Baghdadi rabbinic master Saadia Gaon and Moses Maimonides, as well as iconic moderns like Theodor Herzl and the poet Leah Goldberg, all of them written by comparably distinguished experts for the general Israeli reader.

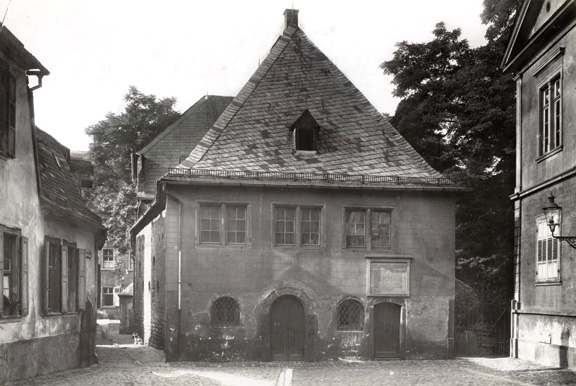

Rashi’s life, according to Grossman, can be summarized briefly since we know very little about it. He was born in Troyes, the center of the county of Champagne in northeastern France. After initial studies with his father, an otherwise unknown figure, Rashi went off to Mainz to study with Rabbi Jacob ben Yakar and his successor there, Rabbi Isaac ben Judah. Rashi left Mainz for the rising academy in nearby Worms where he continued with Rabbi Isaac ben Judah. Soon back in Troyes, he began his own academy while continuing to correspond with his former teachers in the Rhineland. He was not a professional rabbi—there were none until much later—and it is unclear how he made his living. One source implies that he did so by winemaking, a suggestion that has become part of his historical image, though scholars have questioned it. Grossman, who has examined the evidence, leaves the matter open.

Rashi had no sons, but his daughters probably had more Jewish learning than most Jewish girls, as has been true for the daughters and wives of rabbinical figures well into modern times. (My wife’s maternal grandmother, the daughter, sister, and wife of Vilna rabbis, corresponded in Hebrew with family members and conversed in Hebrew with the great modern poet Chaim Nachman Bialik when they met in Tel Aviv.) In any event, his daughters’ learning and piety have entered into legend. They certainly married important rabbinic scholars: Yocheved married Rabbi Meir ben Samuel, and among their four sons was Rabbi Samuel ben Meir, known by the acronym Rashbam, an important Talmud and Bible commentator. We can overhear an active give and take between Rashi and his grandson Samuel in the latter’s biblical commentary. In his commentary to Genesis 37:2, Rashbam famously writes of his grandfather:

He conceded to me that had he enough time he should produce other comments in accordance with the plain-sense meanings that are being rediscovered every day.

Maybe Rashi said it and meant it. Maybe he was flattering his grandson or just putting him off (“Can’t you see I’m busy? I have no time for this!”). In any case, new approaches to the classical texts of Judaism were the subject of family debate and free expression between generations.

Samuel’s younger brother was Rabbi Jacob ben Meir, Rabbenu Tam, the most important tosafist commentator on the Talmud. Rashi’s daughter Miriam married Rabbi Judah ben Nathan (known as Riban), some of whose Talmud commentaries have been preserved. The third daughter, Rachel, married someone less famous, and there may have been a fourth daughter. Through his sons-in-law and grandsons, Rashi established a dynasty in northern France that rivaled and eventually supplanted that of his teachers, especially after tragedy struck the towns of Mainz and Worms, as well as other German centers of rabbinic Jewish life in the spring and summer of 1096.

Pope Urban II’s call to the knights of France to mount an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem to fight Muslim Turks and liberate Jerusalem—the First Crusade—triggered a local massacre of Jews living in the German towns where Rashi had studied and other Jewish communities nearby. The frenzy that called for fighting one kind of non-

Christian enemy spilled over into a series of riots in which armed Christians forced Jews living in German towns to choose conversion to Christianity or death.

Rashi never refers specifically to these horrific events, though Grossman believes that this may be because Rashi completed his commentaries before 1096. This is hard to prove because Rashi kept revising his glosses. Grossman also thinks that one piyyut (liturgical poem) seems to allude to the massacres and martyrdom of his former teachers and colleagues who remained in the Rhineland, but this is not obvious from the poem’s generic language about Jewish persecution. His very first comment at the beginning of Genesis quotes a rabbinic midrash that insists that God created the world to show that it all belongs to Him and that He could give the Land of Israel to the Jewish People. Was he aware that Christians and Muslims were fighting over the Holy Land at that very time? It is hard to prove one way or the other. Rashi continued to teach Talmud and Bible to his students in Troyes until his death in 1105.

For centuries, Jewish boys, and much more recently girls, have begun their elementary Jewish educations by studying “Chumash with Rashi.” Indeed, the first dated Hebrew book to appear in print is Rashi’s commentary on the Pentateuch, in 1475. We call “Rashi script” the cursive smaller script printers designed for any commentary to the Bible because when we think of a Bible commentary we think first of Rashi’s, which itself generated some two hundred “supercommentaries.” The exegete had himself become the text. How are we to understand his extraordinary shelf life? Did Rashi last because he made classical Jewish texts clear as never before? And what does it mean to make a biblical text “clear”?

Grossman’s Rashi tries to answer these questions and many others, and it is full of new ideas. Even Rashi’s familiar acronym gets a fresh treatment. If it refers to R-abbi Sh-lomo b-en (son of) I-saac, then, in standard rabbinic literary practice, it should have been, “Rashbi.” Grossman suggests that the name might instead be shorthand for a phrase his

students used when they referred to him: RA-bbeinu SHeYIhyeh (our Master, may he live), which was later misinterpreted to refer to his name and patronymic, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki. Maybe. It’s a clever suggestion for a problem that most scholars pass right by.

Grossman also addresses the fundamental question of what Rashi was trying to do in his biblical commentary. Does Rashi comment only when the text itself has an ambiguity that, as it were, triggers a comment? Or, does he introduce comments that express his own point of view independent of any textual difficulties? In other words, was Rashi a conservative reader of text or an independent thinker who addresses both the text and the world in which his readers lived? Grossman’s answer is found in the structure of the book, which he divides into three main sections. The first section treats Rashi’s life and the “social network” of his intellectual circles. The second discusses his major writings, especially the Bible and Talmud commentaries. The third looks at Rashi’s views on such matters as the people of Israel and their relationship to God, Torah study, and human dignity. Each part flows from what precedes: the life to the types of writings to their religious content.

In this approach, Grossman agrees with the religious educator and scholar Dov Rappel and with the great historian Jacob Katz, who presented Rashi as not only a commentator but also a religious and social thinker in his own right, particularly with regard to his comments about “the nations” of the world. As plausible as this may seem, there have been others who have seen things differently. Among the most influential of them was the great Israeli Bible teacher Nechama Leibowitz, who always presented Rashi as responding to a specific textual problem. Of course, there is not really a decisive way to resolve this dispute, but it is useful to see Grossman’s approach in action.

Grossman shows three instances in which Rashi emphasizes that the world depends on Israel’s acceptance of the Torah. In his comment to Exodus 32:16, “the tablets were God’s work” (or “occupation”), he writes:

It is like a person who tells his neighbor that his sole occupation is doing such and such; so, here, the Holy One blessed be He’s sole occupation is with [giving the] Torah [to Israel].

The world was created so that Israel would accept the Torah. This central idea is re-emphasized in at least two other key moments in the commentary. Genesis 1:31 speaks of “the sixth day”(yom ha-shishi). Rashi remarks upon the “the”:

The Lord added “the” to “sixth day” [the definite article heh, which, as the fifth letter of the alphabet also signifies the number five] at the conclusion of the act of Creation to state that He conditioned them [all that had been created] on Israel’s acceptance of the five books of the Torah.

Grossman also invokes Rashi’s commentary to Psalms 40:6, “The wonders You have devised for us,” which Rashi, perhaps surprisingly, explains by saying that “For us you created your world.” Here, and elsewhere, Grossman reads Rashi as underlining his central values even when there is no exegetical problem to solve.

Ever since that summer with Dov Rappel in the Poconos, I have accepted this basic approach to reading Rashi. If the matter can be settled, and I am not at all sure that it can, one would need to conduct a systematic rereading of all the passages that the historians have pointed to as expressing Rashi’s specific theology. But it’s a subtle matter. Showing that some of the examples historians cite as Rashi’s expressing his own views may be grounded in the biblical text does not prove that all of them are. Moreover, we still have to account for Rashi’s rewriting or omitting earlier midrashic sources with differing views from those he included in his commentaries, as well as for his patterns of repetition. Until we have a thorough review of the data, it seems to me that the burden of proof is on the Bible scholars who deny the examples that Rappel, Katz, and especially Grossman have adduced to prove their case that Rashi was a thinker and teacher to his generation and, it turned out, to all generations. It is just possible that Rashi was so successful, especially in his Chumash commentary, because he made the text clear not only as a literary work but also as a religious survival manual for Jews living in a very Gentile world.

Given the importance of Grossman’s subject and book, we have to raise the question of the audience of this English translation. In light of the Hebrew words and other technical terms that are found throughout the book, a glossary would have been a good idea, as we find in the charming little volume Elie Wiesel wrote on Rashi for the Nextbook series, but this alone would not have done the trick, since Wiesel wrote with an American audience in mind, while Grossman wrote the Hebrew edition of this book with the educated Israeli reader in mind, which is not the same thing.

The Littman editors could have asked Grossman to adapt the book for the average American or British reader, but, admittedly, that would have been asking a lot, especially since Grossman had already produced three book-length treatments of Rashi. However, it becomes clear from reading almost any section of this admirable book that most English readers will lack the Jewish and scholarly literacy that the Israeli original took for granted. Educated readers who never heard of Rashi, or have only a very general notion of who he was, will quickly find themselves in a minefield of technical terms and learned allusions. What, such readers may wonder, is meant by the “covenant between the pieces,” Abram’s sealing of his covenant with God, in Genesis 15. Some key Hebrew terms, such as “ma’aseh merkavah and ma’aseh bereshit” (the first refers to Ezekiel’s terrifying vision of the divine chariot and esoteric mysteries of the divine more generally, the second to the process by which the universe was created), are left untranslated, and Hebrew book titles abound. At one point, Grossman refers to the great 19th-century Judaica scholar Leopold Zunz as “Zunz” without further specification, and his name is not in the index. The study of Judaism that Zunz pioneered is referred to as “jüdische Wissenschaft” but without explanation about what that was. All of this required editorial rethinking for an English-reading audience without broad Jewish learning.

In at least one instance such problems extend to the translation itself. As someone who has perpetrated enough howlers of his own over the years, I am aware of living in a glass house. Still, let the reader beware when he or she reads about “the edicts of 1096.” The Hebrew word gezeira does indeed mean a “decree” or “edict,” but the phrase gezeirot tatnu refers not to an edict issued somewhere in 1096 but rather to a divine “decree” that permitted, as it were, the horrific anti-Jewish riots or persecutions of 1096 in Germany that accompanied the launching of the First Crusade.

Such reservations, however, should not diminish the scholarly achievements of Avraham Grossman, to which this book attests on every page. A patient reading of Rashi reveals how its subject left “an indelible mark on Jewish culture . . . greater than that left by anyone else since the completion of the Talmud.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On the Importance of Booing Mayne Yiddishe Mame

How did Zionist elites create a new national identity for rank and file members whose ideals did not match their own?

Two Poems

Two untitled poems by Avraham Halfi, translated by Leon Wieseltier.

A Lone Soldier

Every year, when Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s memorial day, rolls around, the author thinks of an idealistic college student named Alex Singer who became a lone soldier in the IDF.

Pessimism Not Despair: A Reply to My Critics

"Just as the turmoil aroused by Israel’s new government has overlooked the Palestinian issue while concentrating on a more immediate crisis, so have the responses to my article."—Halkin writes back.

Shimon

Thank you, Mr. Marcus. Rashi on the chumash has certainly had an immense influence. It encapsulates, edits, and serially presents Jewish tradition in such a way that one hardly knows that a grand process of invention is going on. For countless Jews of all ages, rabbinic thought was and still is filtered through Rashi. A friend of mine called him "the Jewish Leonardo," and he was certainly a great inventor; but his genius was more unobtrusive, patient, and practical. He carefully sewed together the oral and written tradition, verse by verse, until for most readers the seam disappears. Even when his words sit only a few millimeters from contradictory words by Ibn Ezra or Rashbam. His consistency and brevity make him tower over the others.

Rashi's more obviously creative counterpart, and the proper sharer of any prize for most influential Jewish writer since the Talmud, is Moshe ben Shem Tov de Leon, who claimed to have rediscovered the Zohar. Like Rashi, R. Moshe combined "traditional" content with the text in a way that has satisfied and spurred the imagination of thousands. He made his synthesis equally "real" for many (including many who know better). His creative and contrarian interpretations inhabit the text side-by-side with Rashi's midrashic ones; people base their daily lives on their patient creations. It is remarkable.