Neither Friend nor Enemy: Israel in the EU

This summer I finished a five-year term as a member of the European Parliament (EP), so I was not as shocked as I might have been when, in July, Italian celebrity philosopher and fellow Member of Parliament Gianni Vattimo said that he “would like to shoot those bastard Zionists” and suggested that we Europeans ought to raise money “to buy more rockets for Hamas.” This was extreme even by the standards of the European political and academic elites, and Vattimo has since said that he regretted the remarks, which he made on a controversial Italian talk-radio show—then he went on to compare Israel to Nazi Germany.

I was elected to the EU Parliament on behalf of Lithuanian liberals and joined the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), which is the third largest group in the EP, and, as it happens, also Vattimo’s party. As a child of the Soviet Union, I have had a lifelong interest in human rights and soon found myself on the EP subcommittee dealing with these issues. This brought me to the center of debate with such non-EU countries as China, Iran, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia—and Israel.

Of course, I had known about the idiosyncrasies and obsessions of the European left (which are not entirely unrelated to the Soviet ideology of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s under which I lived). Even so, I was struck by the degree of bias, hostility, and willful disinclination to actually engage with the complexities of the Middle East.

Along with others (especially representatives of Great Britain, Germany, and the other Eastern European countries), I often found myself defending Israel in formal and informal parliamentary settings. Even when, in my judgment, a defense was not necessary or appropriate, I tried to bring a sense of historical context and comparative perspective that were too often missing from these discussions. However, what I did not do was reply to every prejudiced remark made by members of the European political elite. As a relative outsider—an Eastern European and a Jewish one at that—I felt that it was not for me to maintain the decency of political discourse among the legislating (and chattering) classes of Brussels and Strasbourg. Nonetheless, it may be the unguarded remarks, visible grimaces, and Pavlovian acts of rhetorical legislation in which the EU’s Israel problem shows up most clearly.

A couple of years ago, there was an effort in the Israeli Knesset to restrict, in various ways, the actions and influence of Israeli non-governmental organizations (NGOs). I regarded this effort (which eventually failed) as deeply misguided and inappropriate for a democratic country. Still, it was shocking for me to hear Annemie Neyts-Uyttebroeck, a noted Belgian politician and my fellow liberal in the ALDE group, compare the Israeli legislative proposal to the overtly totalitarian anti-NGO law adopted in Russia, which regards all NGOs as foreign agents. Vladimir Putin’s Russia is, to say no more, a rogue state that openly supports terrorism, disrupts economic and political life in neighboring countries, and increasinglybears a family resemblance to prewar European fascist states.

Neyts-Uyttebroeck’s comment seems tame indeed compared to the memorable words of a socialist member of the EP—also from Belgium—Véronique de Keyser, who said that she would like to “strangle” Israel’s ambassador if he discussed Israel’s security with her. When famously dovish then-President of Israel Shimon Peres addressed the European Parliament in Strasbourg on March 12, 2013, she refused to rise in his honor, as did many center-left and left-wing MEPs. Would they have done the same, I wondered, if Putin had been the guest? One somehow doubts it.

Then there was Ivo Vajgl, another ALDE colleague of mine, a professed liberal from Slovenia famous for his predictable anti-Israel tirades. Vajgl reached the heights of absurdity when he described Israel as an irrational partner in comparison with the rationality of Egypt—on the eve of the Arab Spring.

The real irrationality in all of these remarks is, of course, distinctively European, and it has multiple sources. It would be easy—and not entirely wrong—to trace this irrationality, not to say hatred, to the enduring legacy of Christian anti-Judaism, the racial anti-Semitism of the 19th and 20th centuries, and the distinctive anti-Semitic heritage of the European left—that is, as the 21st – century incarnation of Europe’s “Jewish Problem.” But there may be other less venerable factors at play as well.

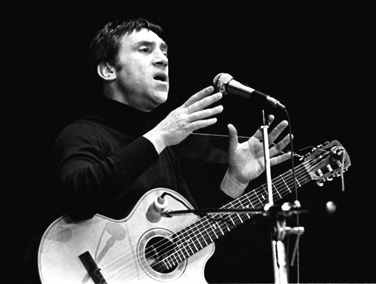

The legendary Russian singer-songwriter, poet, and actor Vladimir Vysotsky wrote a song for the 1967 film Vertical called “Song of a Friend,” which became the song for soulful young Soviets who could strum a few chords on an acoustic guitar (imagine a Russian “Blowin’ in the Wind”). The opening lyrics, in my rough translation, go something like this:

If your friend turned out not to be one

Neither friend nor enemy but something in between

If you are unable to determine if he is a good man or a bad man

Take a risk, bring the man to the mountains and you will see who he is

These lyrics often came back to me as I sat in the EP when Israel was being discussed. For despite all the parliamentary invective quoted here (and I could give many more examples), the EU is certainly not Israel’s enemy, but it would be hard to call it a friend.

Although I have noted (and for present purposes bracketed) the histories of anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism in Europe, the legacies of World War II and the Holocaust are unavoidable in understanding European attitudes toward Israel (the seemingly irrepressible comparison of Zionists to Nazis by Vattimo and his ideological compatriots is a kind of symptom of this). Eastern and Central Europe still have difficulty in handling the history of the Holocaust, especially when it comes to local collaborators with the Nazis. A silent refusal to regard the Jews as their own citizens rather than people from some historical parallel reality has led quite a few Eastern and Central European politicians to whitewash their complicated history, thereby trivializing the Holocaust, distorting the facts, relativizing war crimes, and desecrating the memory of the dead. Of course, the Hungarian fascist party Jobbik goes a great deal farther than that. In November 2012, Márton Gyöngyösi, the party’s deputy parliamentary leader, posted a video in which he stated that it is time to count people of Jewish ancestry living in Hungary, especially those who work in the Hungarian Parliament and the Hungarian government, because they pose a national security risk to the country. Still, on the whole, it cannot be denied that the European center-right—especially in Eastern and Central Europe—is far friendlier to Israel than the Western European left.

On the other hand, Western European politicians are far more attentive than their counterparts from Eastern and Central Europe to the necessity of Holocaust education, the importance of acknowledging difficult truths of history, and the political and moral imperatives of collective memory. This is to say that Western European politics with regard to Israel and the Jewish people fail exactly where Eastern and Central Europe succeed and vice versa.

The Western European left has never understood Israel and Zionism as a framework for the Jews’ political self-determination. This failure turns, in part, on a conceptual myopia of European leftists that has nothing to do with Israel and everything to do with Europe and the EU project: a failure to recognize the difference between liberal patriotism and radical nationalist chauvinism.

The EU itself would have been and continues to be unthinkable without the sort of liberal consensus that leaves little room for patriotic and nationalistic sensitivities. Any form of nationalism stands as a threat to the EU’s benevolent neutrality and a still-nebulous European solidarity. It likewise regards religion, no doubt correctly, as something that must be kept away from politics. But there is a cost to this, for such an attitude occludes a deeper and broader perspective on Europe, which is itself unimaginable without Christianity and its sociocultural incarnations.

Europe’s forgetfulness, or repression, of its religious history has two consequences with regard to Israel. First, it allows the European elite to forget or ignore Europe’s long history of anti-Judaism and regard anti-Semitism as merely a form of modern racism. Second, it engenders hostility toward a modern state, such as Israel, that acknowledges its religious roots. Another way to put this is that Israel and Zionism are the two mirror images of Europe and its history that it dislikes the most.

Israel is, then, everything Western Europe is not: a successful latecomer to the modern world of nation-states endowed with the whole package of modern experiences, anxieties, passions, sensibilities, and forms of solidarity.

The nation-state in Europe, by contrast, seems to have been a short-lived and passing phenomenon. Until the 20th century, Europe knew of no such entity; France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Spain, and the Habsburg Empire were all continental or overseas empires. It was not until the demise of such empires after World War I that nation-states came into existence, including the Eastern and Central European countries. From this perspective, the nation-state in Europe seems a mere passing phenomenon, a short stop on the way from monarchies and empires to the EU in its present (if rather loose) form.

These, then, are the outlines of the cognitive, moral, and political map of the EU. On that map, Israel stands out as a disturbing anomaly, and consequently, as neither friend nor enemy, but something in between.

I have written of the subterranean role that the memory and repression of the history of the Holocaust have in determining the place of Israel in European political discourse, but I have not yet mentioned the role it plays in my own life and perceptions. When I was growing up, my father refused to tell me anything of our family’s experience in the Holocaust. Although he was a native and fluent speaker of Yiddish who knew a great deal about the history of Jewish life in Lithuania, he withdrew completely from the Jewish community after World War II and brought me up as a Lithuanian. As he later put it, he had seen hell on earth only because he was a Jew, and he did not want his sons to undergo that experience.

In 1989, as the Soviet Union was crumbling and Lithuania began to move toward independence, my father and I were able to visit America and reestablish a connection with a branch of our family that had immigrated there in the 1930s. It was only then, in America, and when I was already an adult, that my father was able to tell me about his experience in the Holocaust. On September 9, 1941, in the small town of Butrimonys, not far from Kovno (Kaunas), where my family lived, Nazi Einsatzgruppen together with local Lithuanian perpetrators rounded up the Jews of the town and massacred all but 11. Among the survivors were my father, uncle, and grandparents.

I never mentioned this family history to my parliamentary colleagues, not even when hearing Israel casually compared to the Third Reich. There are many reasons for this, one of which is that I do not choose to discuss deeply sensitive matters with those who cloak European narcissism or a cynical pragmatism (or both) in moral indignation. Nor do I think that my family history gives me unique moral and political insight. Nonetheless, it does help to inform my perspective—one that is just as uniquely European as that of my colleagues—on the rhetoric and reasoning behind the EU’s friendship, or lack thereof, with Israel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On Chaim Grade’s Agunah

Chaim Grade’s Yiddish novel The Agunah is not so much a story about one woman’s plight as much as a whole city’s eruption over her story—the rabbis, the butchers, the mohels, the barbers, the housewives.

Athens or Sparta? A Rejoinder

Accused by Patrick Tyler of unfairness, Morris presses on.

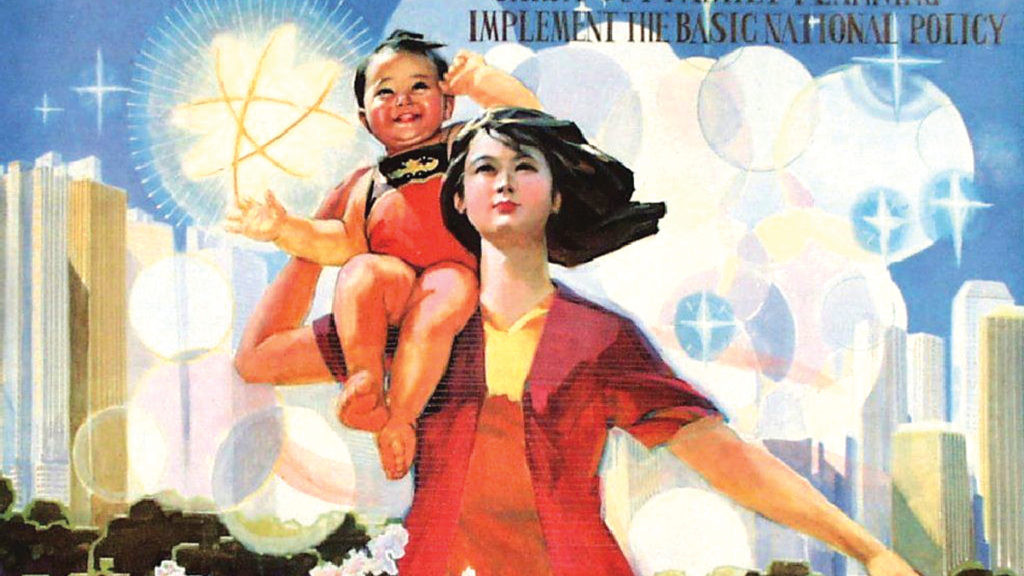

On Not Bringing Up Baby

What happens when the rising cost of raising children meets the downward pressure on reproduction?

Publishing Godliness: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Other Revolution

Much of the discussion of the Rebbe's legacy focuses on his charisma, his saintliness, and his organizational skills, but first and arguably foremost, he was a book publisher.

jerryjblaz

I don't believe for one moment that the Jew-hatred of Europe was washed away by the blood of the 6,000,000. And for that I must say that I don't know why Jews stayed in Europe. In 1945, world Jewry looked at Europe as one immense Jewish graveyard, and I thought that for certain Jews would flock to the Jewish state then in it formative years. But that is the past, and in the 70 years that have passed, Israel was established, and became one of the strongest nations in the world, possessing much intellectual power and the seventh largest armed forces in the world. It was once a "David," but no longer.

In fact, most of the witnesses to Israel's years of tribulations have passed from the scene, and the failure of this powerful state, as it is seen today,to achieve peace is regarded by many as a result of the hubris of a powerful state. So the very national state that was supposed to be the solution to anti-Semitism has become a source of anti-Jewish feelings. Yes, there are old anti-Semites still present in Europe and in the world, but there has arisen a generation that did not know the holocaust; it is something in a history book, a large number, but a notation of the dry recitation of the past. Leading BDS and other anti-Israel campaigns are people who did not witness this greatest of human and Jewish tragedies we call the Shoah.

No matter how many Nobel Prize winners Israel has, it will not convince any of the anti-Israel people to love Israel. The only thing that might convince the anti-Israel groups to view Israel more favorably is Israel making peace with their neighbors, the Palestinians, but Israeli governments like the current one do not seem up to that important task.