On Chaim Grade’s Agunah

Chaim Grade’s Yiddish novel The Agunah is not so much a story about one woman’s plight as much as a whole city’s eruption over her story—the rabbis, the butchers, the mohels, the barbers, the housewives. Published in 1961, Grade’s novel doesn’t just tell the tragic story of a woman and her suitor; it depicts the whole Jewish ecosystem into which the author had been born and that he had seen destroyed in the Holocaust less than two decades earlier. And yet, as I reread it recently, I couldn’t help but think about contemporary Orthodox Jewish society in America and its literature, or lack thereof.

A few years ago, my mother-in-law handed me a copy of Grade’s novel in Curt Leviant’s elegant, fluent English translation. She had run across it in the library of her late grandmother and thought I would find it interesting given my reporting on the lives of religious Jewish women. And she was right. Recently, after writing about the problems and strategies of modern-day agunot, women whose husbands have refused to give them a get (the halakhic bill of divorce that would allow them to move on with their lives),I found myself returning to The Agunah.

Grade’s tragic heroine is Merl, a dark-eyed seamstress living in a small house in the outskirts of Vilna, Lithuania, sometime in the 1920s. Her husband, Itsik, was missing in action on the battlefields of World War I, thus rendering her an agunah, not because her husband won’t divorce her but because his death has not been legally confirmed. Until that happens, she cannot remarry, but she is more or less reconciled to her predicament. Her only suitor, a wealthy bachelor named Moishe Tsirulnik, disgusts her, and so she lives in a kind of wistful limbo until she meets a widower named Kalman Maytess in a cemetery fifteen years after Itsik left for the front:

Alone, she stared at the fresh grave, as though asking her departed friend whether she ought to remarry. On the other side of the hill stood the cemetery cantor, a man in his forties, leaning on his cane and gazing at the seamstress. Having overheard Merl’s friends’ remarks, he asked if she wanted him to chant a memorial prayer; when Merl nodded, he asked her name and her father’s name. He began to chant, then stopped, waiting for Merl to provide the names of her husband and children. He wanted to be sure that he had heard correctly that this woman was all alone in the world.

They walk out of the cemetery together in the twilight. It is not love at first (or even second) sight, but after they part, “Merl rested her head on the bannister and realized that her mother had been right. Itsik was indeed no longer among the living. Oh yes, she remembered him. But she no longer felt him in her heart.” And the cemetery cantor (and house painter), Kalman Maytess, begins to glimpse a happier future for both of them. He speaks with Merl’s mother and discusses the situation with a “recluse in the Vilna Gaon’s Shul” who gives him some halakhic hope:

Chewing the tip of his beard and knotting his brow, the recluse finally answered that there were grounds for discussion. Although a married woman may not remarry as long as she does not have a trustworthy witness to her husband’s death; since this woman had been an agunah for so many years; and since none of the young men who served with her husband’s company had returned; and since her husband had been sickly and could have died a natural death—there were indeed grounds for discussion.

Enter the rabbis of Vilna—characters whose counterparts could easily be found in any modern-day Orthodox community: Reb Levi Hurwitz, a zealot who has no trouble turning “away a weeping agunah”—or her hopeful suitor. Reb Asher-Anshel, who has a “long-suffering mildness” and chooses to sit through divorce cases silently. A happily married man, he is “famous for his reticence in granting divorces” because he believes most couples can be reconciled.

And then there is the obscure but lenient rabbi, Reb David Zelver, whose small, out-of-the-way shul used to be the location of the great nineteenth-century saint Rabbi Israel Salanter’s yeshiva. When Merl approaches him, he at first resists despite his sympathy. “I’m only a district rabbi,” Zelver says, his fear of taking another unpopular stance palpable. His wife drives the agunah out of their tiny apartment, afraid that her husband will eventually pity the woman and free her. “The rabbis and the rich householders are our enemies,” the rebbetzin yells at Merl. “Do you want to bring more grief down upon us? All the rabbis have forbidden you to marry, and you want my husband to permit it? The town will stone us.”

Zelver finally authorizes Merl’s marriage to Kalman, knowing that he will soon face community rage and that he would have to accept “the persecutions silently and with quiet obstinacy.” He prays to God for guidance: “I also have suffered and continue to suffer from people’s cruelty. But nevertheless, I know that the Torah is not responsible, even though Torah scholars are often blind to other people’s misfortunes.” But when Kalman is given a Torah scroll to carry during a Simchat Torah celebration, the Main Synagogue’s two shameshes descend into blows over whether a husband of an agunah is permitted to be honored.

Merl’s story quickly spirals into class warfare: the market youths defend the honor of the poor assistant shamesh who had assisted in the controversial marriage of the agunah and the pauper; the synagogue trustees, the machers, threaten to resign over the honor of the senior shamesh. Meanwhile, Merl’s spurned suitor, Moishe Tsirulnik, decides to take advantage of the moment and riles up the butchers and the housewives of Vilna: “If steer meat slaughtered by a pious shokhet in Oshmeneh is declared not kosher in Vilna because it’s considered illegally imported,” the secular Tsirulnik cynically argues, “how come someone else’s wife is yes kosher?” Soon, the clean-shaven bachelor is convincing Vilna’s pious zealots to break the windows of the city’s rabbis for allowing an agunah to remarry. “Only the agunah herself was not mentioned, for no one knew her,” Grade’s narrator comments dryly.

Grade’s story takes place in synagogues and homes but also beer taverns and marketplaces, the whole map of Jewish Vilna, a network of dining tables and scholars’ desks, a landscape dotted with kerchiefs and teakettles and Torah arks:

The slap in the Main Synagogue was constantly discussed in the poor courtyards and in the streets bordering upon the Synagogue. The market youths also dealt with the matter in their own unique fashion: They didn’t give a damn about the agunah affair. They had heard of more intriguing romances. Even Paris had nothing on Vilna. If all the young men and women in Vilna had cast but one-tenth of their sins into the water on Rosh Hashana, the Vilia River would have overflowed its banks and inundated the city. The market youths said that the only thing that interested them was the quarrel of the religious functionaries.

And contrary to expectations, the lenient Reb David Zelver is not the only sympathetic rabbinic character. Grade offers deft, fully human portraits of all of the rabbis, each privately dealing with the mess of their lives, their own human ambitions and sorrows. Even the embittered Reb Levi is secretly grieving over a mentally ill wife and daughter, and though he knows he could secure a heter meah rabbanim (a kind of de facto annulment signed by one hundred rabbis, which allows a man to remarry even if his wife is unable or unwilling to receive a get), he himself chooses to live the life of one chained to a dead marriage.

“You want to be persecuted,” Reb Levi the zealot charges at Reb David. “You’ve convinced yourself that you are suffering for being a man of truth. But the fact is that you suffer for your pride.”

“Ah, woe unto the world that has lost its leader, and woe unto the ship that has lost its captain,” Reb David retorts. “If Vilna’s rabbis weren’t such cowards, they would excommunicate you for persecuting a tormented woman.”

Both rabbis, as Grade’s subtle novel makes clear, are right.

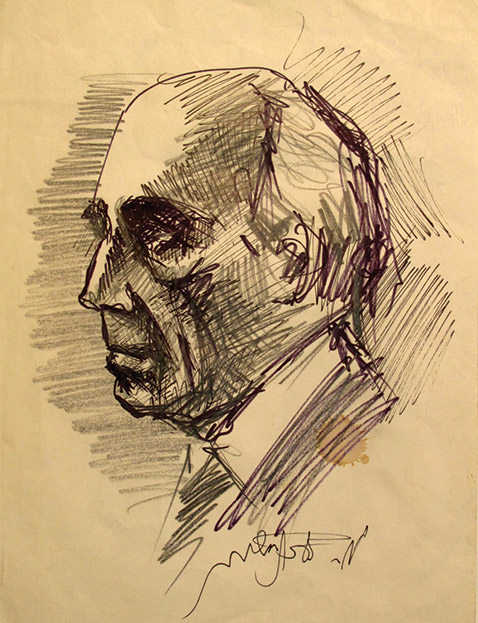

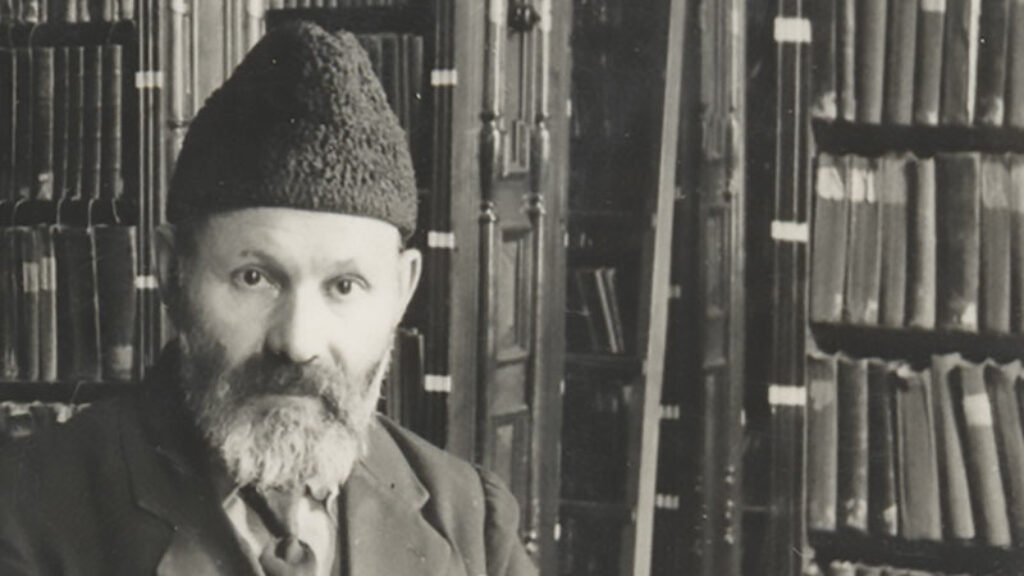

Chaim Grade was raised in Vilna in a literate Jewish family. His father was a Hebrew teacher who read secular enlightenment literature, but Grade attended the renowned Novardok yeshiva, whose students were famous for their asceticism, scrupulous approach to ethics, and disdain for secular culture. He also studied for several years as the private student of Rabbi Avraham Karelitz, the great talmudic scholar known as the Hazon Ish, who would become the leading rabbinic authority in Israeli haredi society after the founding of the state. In the end, he was more interested in poetry than talmudic reasoning. For Grade, “literature could do what Talmud study could not,” said Ruth Wisse. It could evoke an emotion and even conjure the lost world that halakha had, in part, created.

When the Nazis invaded Vilna, Grade was able to escape to the Soviet Union, but his wife did not get out and was murdered in the city’s ghetto. After the war, he moved to Paris and finally to the United States in 1948. In New York, he began to write narrative prose, most famously his memoirMy Mother’s Sabbath Days; his philosophical dialogue “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner”; and his sprawling novel The Yeshiva, each of which reflects both his deep knowledge of European Jewish life and tradition and his inconsolable sorrow over its destruction.

Unlike his contemporary (and bitter rival) Isaac Bashevis Singer, who told stories of individuals, Grade took on entire communities, cities, yeshivas, synagogues in an attempt to breathe life into a destroyed universe. His books are long, his friend and translator Leviant told me, because “they incorporate many individuals and communities, in an almost Tolstoyan way. He is trying to recreate what the Germans destroyed. It’s a techiyat hameitim, a resurrection of the dead.” And indeed, in his rendering of the cacophony of the painters and the market youths and the paupers, the rabbis, the shameshes, and the synagogue trustees, he performs a literary miracle—the infighting leaps off the page. These fictional Jews, whose inspirations likely lie in the mass graves of Ponary, are suddenly resurrected.

Halakha and its interpretation play a central role in all of Grade’s work. This is rare among Yiddish novelists, who either did not grow up in the all-consuming textuality of yeshiva life or left it so definitively that little of it lingered. In The Agunah, he asks us to consider who is allowed to benefit from halakha, and who is allowed to suffer from it? Is the question of Merl’s fate really a matter of the sober, unbiased interpretation of God’s word as it is filtered through the Talmud and its commentaries—or is it a matter of ambitions and rivalries?

It is likely that Grade based Merl’s story on that of a real woman in Vilna. When I asked Leviant about this, he told me a story. After translating the novel, Leviant told Grade how sad Merl’s ultimate fate made him. “Zorgt aykh nisht, al tidag,” Grade told him. “She is well in Chicago.”

In the last few months, in the shtetls of Monsey and Lakewood, and elsewhere, the agunah issue has returned as a cause—women stand outside recalcitrant husbands’ homes with blaring bullhorns and iPhone cameras rolling, demanding that they give their estranged wives a get. These women’s predicaments are different from Merl’s—their husbands are all too present, not missing in action—but the arguments over rabbinic power and leniency haven’t changed much; though, of course, the channels have changed. Now the arguments are on Twitter and Instagram, not in the Vilna marketplace; instead of Grade’s market youths, millennial influencers are now self-righteously, but sometimes successfully, seeking justice. Meanwhile, the Rebbe Levis of the world use WhatsApp to spread long voice notes decrying the immodesty of the daughters of Israel. What we seem to lack now, however, is a literature that honestly depicts this world.

In Grade, I recognize this world, my world; it is one brimming with the stories of my daily life as an Orthodox writer but also as a rabbi’s wife. The dramas of Polotsk Street in the 1920s are not so far removed from the dramas of Lexington Avenue I see playing out in the 2020s. It is a thoroughly human story—one of power struggles, comedies, tragedies, ulterior motives, and ambitions. The housewives of Grade’s marketplace and the drunkards in his inns could be transplanted into the aisles of our gourmet supermarkets and onto the barstools of our glatt kosher restaurants. Reading Grade, I find the literature I yearn for, for it is in many ways the closest rendering of traditional life as I know it. In modern American Jewish literature, stories of traditionalist life emerge either in the defensive and sanitized literature of internal frum publications or in the prosecutorial literature of those who “go off the derekh,” telling now-familiar exodus stories in which secularism alone offers redemption.

In contrast, Grade offers us a rich portrayal of religious life, a life governed by halakha and strict social mores but also riddled by the challenges of balancing rabbinic interpretations of divine law and messy real life in the diaspora. Jewish religious life like this exists here in America, but one wouldn’t know it from contemporary American Jewish literature.

Grade was a yeshiva-student-turned-writer, whose mind never lost the talmudic cadences of his youth. He wove rabbinic texts into his prose; his imagination was gripped by his characters, by their anger and their passion and, perhaps most of all, by their humanity. And until an honest and contemporary Orthodox literature emerges, we can return to Grade’s pages for a taste of what we lack and for a reminder that, as Solomon once told us, nothing is new under the sun.

Suggested Reading

Chaim Grade: A Testimony

Toward the end of his life, the talmudist Saul Lieberman published his only Yiddish essay, an appreciation for his friend, the novelist Chaim Grade, the great witness to a lost world. Translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

Translating and Remembering Chaim Grade

A memoir of faith, literature, and chickens.

Golden Books

Three decades ago, Allan Nadler went to Vilna to reclaim books that the Nazis had plundered from YIVO, or so he thought. Dan Rabinowitz’s Lost Library solves the mystery—and raises important questions.

Ungoverning the Western Wall

After more ugly clashes at the Western Wall, two Israeli political scientists make a radical proposal.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In