Athens or Sparta? A Rejoinder

There is ill will and there are mistakes, and both are legion in Mr. Tyler’s Fortress Israel and, perhaps more surprisingly, in his response to my review of that book. One might have expected Mr. Tyler to exercise a bit of caution. But, apparently, he is constitutionally incapable of shaking off the old, mendacious ways. He tells us that he “certainly [has] no animus toward the State of Israel,” but Fortress Israel drips with animus. Simply open to almost any page in the book, page 391, for example. Tyler writes: “On April 18 [1996], Israeli artillery gunners targeted—mistakenly, they said—a UN refugee center at Kana [in southern Lebanon] and slaughtered a hundred civilians—women, children, and the elderly—in an inferno of shrapnel and explosion.” One wonders, were there really no army-age males present, but the “mistakenly, they said” tells it all. This is typical Tyler, Fortress Israel epitomized. In fact, Israel subsequently admitted the mistake and, if I am not mistaken, apologized, but this is what happens in wars in which terrorists/guerrillas operate from within and next to inhabited areas, however much their opponents try to take care.

Or take the following passage in his response:

Mr. Morris distorts the scope of archival material available to researchers on the Arab-Israeli conflict. He points with pride to the fact that Israel has declassified a great deal of material and that the Arabs have opened almost nothing. But surely he is aware that the archives of Britain and the United States are probably the greatest sources of information on the Arab-Israeli conflict. As Mr. Morris presumably knows, these archives are rendered in English.

Here is Mr. Tyler at his best, doubling down on the innuendo. He implies that in my works I haven’t used British and American archives and would do well to consult them, though a mere glance would prove otherwise. And he implies that, by contrast, he has used them, thoroughly. But nothing could be farther from the truth. Almost all of the “nearly 1,000 notes” (his phrase) in Fortress Israel refer the reader to secondary sources, newspaper articles, and interviews. Tyler’s book has 846 footnotes—of which less than fifty refer to archival documents (not a proportion characterizing serious works of history). And his footnotes reveal that he has made no use of any British archives, virtually none of any Israeli archives, and such limited and eccentric use of American documents as to render their usage meaningless and misleading. Tyler’s occasional toe-dip into an American archive appears to be geared only to rebuffing the possible charge that he failed to use archives. Nothing more.

Tyler goes into risible contortions to explain away his basic ignorance of the realities of Israel and its history. In my review, I pointed to Tyler’s assertion that Israeli paratroops wore black berets as symptomatic and revealing as to this deep ignorance. (In fact, they wear red berets.) In his rebuttal, he writes: “I have written no such thing . . . [I wrote] ‘In what seemed to be a stab at burnishing a military profile, he [Prime Minister Levi Eshkol] absurdly wore a black beret, a symbol of Israel’s elite commando and paratrooper forces.’ It was the symbolism of the beret, not the color [that I was referring to] . . .”

Let me reiterate: My reading of this passage (it’s simple English) is that Tyler is saying that Israel’s “elite commando and paratrooper forces” wear black berets and that’s why Eshkol donned one. In fact, Israel’s commandos wear red or blue berets. (Sayeret Matkal and Sayeret Tzanhanim wear red berets, while Shaldag, 669, and Shayetet 13 wear blue ones.) Actually, Tyler digs himself even deeper into the pit when he adds a second, more general error in saying that he meant that only commandos and paratroops wear berets. Actually, almost all Israeli soldiers, infantry, armor, artillery, air force, etc., wear berets. Tyler might dismiss all of this as “quibbling.” I would say that his mistakes are symptomatic of his basic lack of knowledge of what he is writing about.

Perhaps more troubling is his continuing tendency to play fast and loose with the truth. In Fortress Israel, on page 212, Tyler wrote: “[In 1970] the Soviet air force sent its own pilots with modern jet fighters and shot down a half dozen Israeli Phantoms . . .” In my review, I said that this was untrue. So now, without admitting error, Tyler tries obfuscation: “During the War of Attrition, the Israeli Air Force lost a number of aircraft . . . due to the arrival of highly competent Soviet air defense forces, including both MiG-21 pilots and sophisticated SAM3 missile batteries. . . I point out in Fortress Israel that Soviet forces shot down a half-dozen Israel Phantoms.” This is (probably) true: Soviet surface-to-air missile crews shot down Israeli Phantom jets. But what he wrote in Fortress Israel, that Soviet MiG-21s piloted by Soviet pilots shot down Israeli Phantoms, remains untrue. The opposite actually happened: Israeli pilots shot down five Soviet-piloted MiGs. Why not simply admit to having made an error?

Tyler does not always operate by way of innuendo, misleading implication, and obfuscation; often enough he indulges in the big lie. In his book, and in his response, he writes that in the Israeli-Egyptian War of Attrition (1969-1970) Israel deliberately bombed “military and civilian targets” and “U.S.-made F4 Phantoms terrorized Egyptian cities,” and that, a decade later, in 1982, it indulged in “saturation” bombing of Beirut. In both cases, he makes it sound like the Luftwaffe’s assault on London and the Allied counter-bombing (and far more devastating) offensives against Germany’s cities in World War II.

These, simply, are lies. In the yearlong bombing of Egypt’s military bases, Israel twice—and mistakenly—hit civilian sites: a school that was located inside an army base and a factory. Otherwise, Egypt’s cities suffered no attacks and life in them went on as usual, though once or twice Israeli jets unleashed sonic booms over Cairo to bring home to Egyptians Nasser’s inability to deal with the Israel Air Force, perhaps to engender public pressure to end the War of Attrition against Israel’s positions along the Suez Canal. The fact that the Israeli Air Force used American-built jets is neither here nor there, except as it relates to Tyler’s clear disapproval of American arms sales to Israel.

In Beirut, when the IDF was besieging the PLO, there was targeting of PLO headquarters and positions, and probably an effort to kill PLO chairman Yasser Arafat—but there was no deliberate targeting of civilians, and no “saturation” bombing, which explains the relative paucity of civilian Lebanese casualties. In his “rebuttal,” Tyler mendaciously cites bomb tonnage as proof of “saturation” or carpet-bombing. The question isn’t one of tonnage but of intent and against whom the bombs were directed and, most importantly, of actual casualty figures. Had Israel engaged in saturation bombing, there would have been many thousands of Lebanese and Palestinian civilian deaths. But over the two months of bombings in summer 1982, civilian deaths were in the hundreds.

Not everything that Tyler writes is wrong. He is certainly right about Ben-Gurion’s sidelining of Moshe Sharett, Israel’s first foreign minister (1948-1956) and second prime minister (1954-1955), in effect giving the defense establishment primacy, as I detailed twenty years ago in Israel’s Border Wars 1949-1956. Sharett tried to reach out to Arab leaders and talk peace. And (as Tyler fails to tell his readers) Ben-Gurion allowed him to pursue the diplomatic avenues, especially between 1949 and 1950 with Jordan’s King Abdullah. But Ben-Gurion simply didn’t believe that the Arab world—Egypt, Syria, and Iraq—was ready at the time for peace or even wanted it. And Ben-Gurion was right. In 1951 a Palestinian gunman assassinated Abdullah because of his secret negotiations with Israel. Other Israel-Arab peace contacts (with Zaim’s Syria and Nasser’s Egypt) led nowhere. Only in the 1970s did there emerge an Arab leader, President Anwar Sadat of Egypt, who was ready to make peace (for which trouble he was soon shot dead by Islamists, who also hated him for his “foreign” wife and suppression of the Muslim Brotherhood). Throughout his self-described “biography” of Israel’s political leaders, Tyler resolutely ignores the reality of Arab rejectionism as a crucial factor in their actions and decisions.

One last point: Tyler says that in “redesigning the nation,” Ben-Gurion in the 1950s “chose Sparta rather than Athens as the model for his nation building efforts.” Were Tyler a serious historian, he would have sought some proof, say a passage or two from Ben-Gurion’s diaries, speeches, or interviews. Something. He doesn’t. In fact, you will find in Ben-Gurion’s writings, indeed almost ad nauseam, the biblical aspiration to fashion Israel as “a light unto the Gentiles.” And in some ways he, and Israel, delivered: a working democracy in a region where there are no others; good universal medical care and a social welfare net; world-class literature and other arts; high-tech innovation; good universities (and, yes, alas, also advanced weapons technologies).

My advice to Mr. Tyler is simple. If you don’t like Israel, go ahead and say so. You think Zionism was and is immoral? Say so. You believe that modern-day Arabs have created just states and open societies? Say so. Or simply write about something in which you are less emotionally involved, say the Peloponnesian War. At least then you might learn something about Sparta and Athens.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

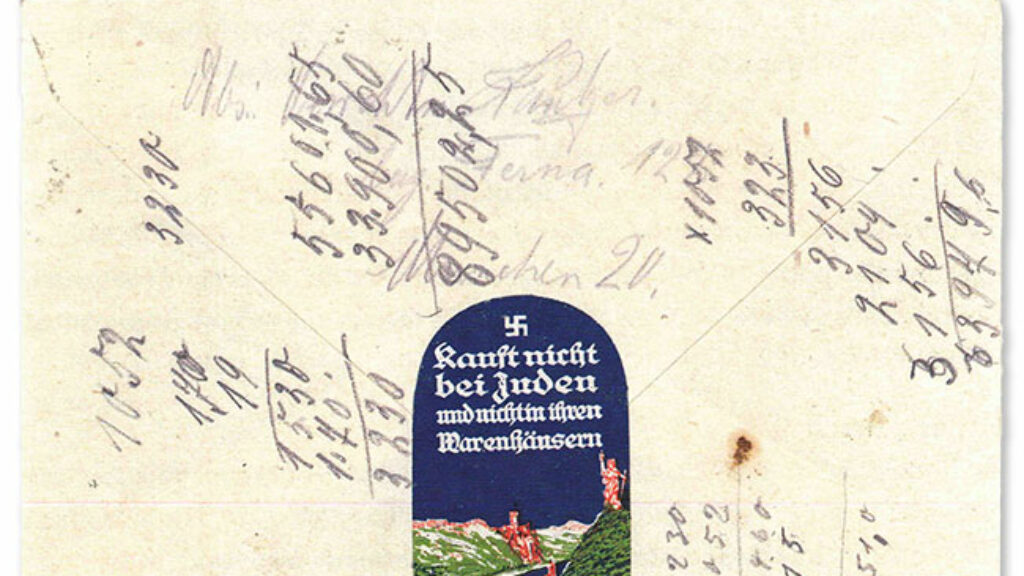

Postcards from the Shoah

Stamps and the paper they traveled on create a historical record of the Holocaust, capturing, for instance, “the exact historical moment when one person reached out in desperation to another."

Of Spies and Centrifuges

Jay Solomon traces decades of spy games between the United States and Iran, a conflict, he writes, “played out covertly, in the shadows, and in ways most Americans never saw or comprehended.”

The Stakes in the Middle East

Reformers and democrats are the real hope for a future of peace, liberty, and stability in the Middle East. This historic moment presents the West with a remarkable opportunity.

Misreading Kafka

The Kafka myths, and the "myth-busters" who make them.

ZEDERJ

Mr. Tyler should have realized he would be no match for Benny.

Gershon Hepner

WHY DID THE FRENCH STOP TEACHING LATIN

“Tell me why the French stopped teaching Latin,

switching to French?” Ben-Gurion said to Guy Mollet,

who hoped Ben-Gurion would throw his hat in

the ring, competing against Nasser in the fray

in which the Israelis were allies

of Frenchmen and of Brits, when they reached the canal

of Suez as their military prize.

The battle that they fought came with the rationale

of changing language that Egyptians spoke

from that of war to that of peace once they had lost.

The rationale was wrong, for no one broke

their swords and turned them into plows, and so the cost

of war became much greater than mere shedding

of blood. The Arabs didn’t switch to words of peace

as French once switched to French from Latin; they were heading

to hate words with a hate it seems will never cease.

An argument I consider a non-starter

is that Israel is in no way aiming to

become like Athens, emulating Sparta.

The deepest aim of every Israeli Jew

is reestablishing Jerusalem,

endowing it it with glories that once came from Greece.

As Sparta Israel do not condemn,

Jerusalem denotes undying quest for peace.

[email protected]