The Banality of Evil: The Demise of a Legend

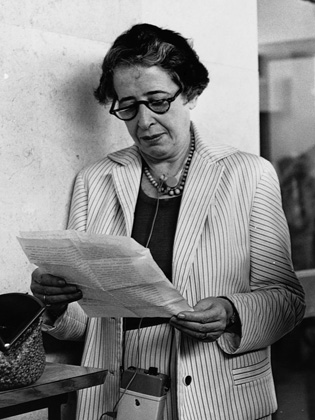

There have been few phrases that have proved as controversial as the famous subtitle Hannah Arendt chose to sum up her account of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann. From the moment the articles that eventually comprised her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil were published in The New Yorker, the idea that the execution of the Nazis’ diabolical plans for an Endlösung to the “Jewish Question” could be considered “banal” offended many readers. In addition, Arendt took what seemed to be a gratuitous swipe at the conduct of the Jewish councils, which, operating under conditions of extreme duress, were forced to bargain with their Nazi overseers in the desperate hope of buying time, sacrificing some Jewish lives in the hope of saving others. Only with the benefit of hindsight do we realize that their efforts were largely futile. In her rush to judgment, Arendt made it seem as though it was the Jews themselves, rather than their Nazi persecutors, who were responsible for their own destruction. Thus, with a few careless rhetorical flourishes, she established an historical paradigm that managed simultaneously to downplay the executioners’ criminal liability, which she viewed as “banal” and bureaucratic, and to exaggerate the culpability of their Jewish victims.

Arendt’s astonishing conclusion that “Eichmann had no criminal motives,” and the account that underlay it, might have been construed as mere journalistic overstatement, but her status as a distinguished political theorist, together with the furious controversy her account engendered—Gershom Scholem famously accused her of lacking ahavat yisrael (love for her fellow Jews)—helped to create an aura of brave truth-telling that has surrounded Eichmann in Jerusalem ever since. This image of Eichmann in Jerusalem as an act of an intellectual bravado, with Arendt herself cast in the role of an imperiled heroine—a latter-day Joan of Arc, persecuted by an army of inferior male detractors—was canonized in the recent and widely praised German film by Margarethe von Trotta, Hannah Arendt.

It is certainly true that throughout the controversy Arendt comported herself as someone who was above the fray. Often she seemed to regard the Israelis she encountered in Jerusalem with as little esteem as she did Eichmann. She dismissed the chief prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, with breathtaking condescension as a “typical Galician Jew, very unsympathetic, boring, constantly making mistakes. Probably one of those people who don’t know any languages.” While covering the trial she wrote to her former mentor, the philosopher Karl Jaspers:

Everything is organized by a police force that gives me the creeps, speaks only Hebrew and looks Arabic. Some downright brutal types among them. They would obey any order. And outside the doors, the oriental mob, as if one were in Istanbul or some other half-Asiatic country. In addition, and very visible in Jerusalem, the peies [sidelocks] and caftan Jews, who make life impossible for all reasonable people here.

Even setting aside the egregious racism and anti-Jewish animus, there is something very alarming about this passage. Any reader familiar with Arendt’s classic study The Origins of Totalitarianism knows that she described such mobs as the carriers of the totalitarian bacillus. Nor can there be any mistaking the import of her assertion that the Sephardic or Mizrahi policemen “would obey any order.” With this claim, Arendt insinuated that they were the “authoritarian personalities” and “desk murderers” of the future. Again and again, one sees how readily Arendt blurred the line between victims and executioners.

Arendt’s banality thesis helped to engender the so-called “functionalist” interpretation of the Holocaust, in which the role of obedient desk murderers and mindless functionaries assumed pride of place. Leading German historians such as Hans Mommsen coined nebulous phrases such as “cumulative radicalization” in order to describe a killing process that, like a Betriebsunfall (an industrial accident), seemed to have happened without anyone consciously willing it. But as the historian Ulrich Herbert has pointed out, at the time the functionalist account was also culturally convenient: “For a long time there was a reluctance to name names in research on National Socialism . . . [Consequently,] there was also massive resistance to studies about the perpetrators and their relationship to German society.” The upshot of this approach was that the Holocaust’s character as a crime conceived and masterminded by German anti-Semitic ideologues that was perpetrated against the Jews disappeared in favor of a series of conceptual abstractions—“modernity,” “bureaucracy,” “mass society”—in which the Jewish (or anti-Jewish) specificity of the events in question all but disappears.

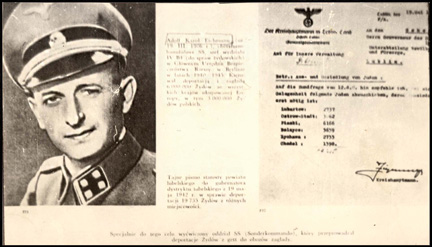

Was Eichmann, or the evil he was instrumental in perpetrating, really banal? Remarkably, it seems that Arendt had already arrived at a definitive judgment of Eichmann’s character some four months before the trial even began. In another letter to Jaspers, written on December 2, 1960, she writes that the upcoming trial would offer her the opportunity “to study this walking disaster [i.e., Eichmann] face to face in all his bizarre vacuousness.” But, as Bettina Stangneth shows in her well-researched and path-breaking study Eichmann Before Jerusalem, Eichmann was, in fact, a consummate actor. “Eichmann,” she writes, “reinvented himself at every stage of his life, for each new audience and every new alarm.” He becomes “subordinate, superior officer, perpetrator, fugitive, exile, and defendant.”

The meek and unassuming Argentine rabbit breeder who took the witness stand in Jerusalem and described himself as “a small cog in Adolf Hitler’s extermination machine” bore no resemblance to the man who, as Specialist for Jewish Affairs of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), reported directly to Heinrich Himmler and had avidly sown terror and destruction throughout the lands of Central Europe. Nor did he resemble the man who, under the alias of Ricardo Klement, had been the toast of Argentina’s highly visible neo-Nazi community, the man who unabashedly signed photographs for fellow fugitives: “Adolf Eichmann, SS Obersturmbannführer (retired).” As Stangneth aptly observes, “Eichmann-in-Jerusalem was little more than a mask.” Eichmann gave the performance of his life, and Hannah Arendt was entirely taken in.

In Jerusalem, Eichmann fought to save his life, and, if possible, to clear his name for posterity. But another one of his central motivations was to throw a monkey wrench into the gears of the Israeli judicial apparatus, whose staff he regarded as his Jewish “persecutors.” During his proud years in the SS, combating the pernicious influence of World Jewry had been Eichmann’s raison d’être. With his artful performance on the witness stand in Jerusalem, Eichmann, ever the warrior, was, in effect, making his final stand. True to the SS creed of loyalty above all (“Mein Ehre heisst Treue”), he went down fighting.

It has long been known that the CIA had been privy to Eichmann’s whereabouts after the war. Hence it was with the CIA’s tacit approval that, in 1950, Eichmann, in order to avoid capture, successfully made use of the notorious “rat line” to South America. Only a few years ago, it came to light that the German Intelligence Services had also been well aware of Eichmann’s various activities prior to his flight to South America. German officials also refused to lift a finger, but, for slightly different reasons. Eichmann, it seemed, knew too much about prominent ex-Nazis who had recently been elevated to the status of “notables”—politicians, opinion leaders, and scholars—in the newly conceived Federal Republic. His apprehension, they believed, would have injured the emerging German democracy. As Stangneth remarks laconically, although the trappings of constitutional democracy had been freshly implanted on German soil, the problem was that “there were no new people to administer them.”

One of the main reasons that Arendt’s banality of evil concept struck a nerve was that it played on widespread fears about the dehumanizing effects of “mass society.” When she wrote about Eichmann, the Nazi threat was past, but, in the war’s aftermath, an arguably greater menace had arisen, the threat of nuclear annihilation. This threat had been vividly driven home by the Cuban missile crisis, which took place the year before Arendt’s articles on the Eichmann trial were serialized in The New Yorker. It was tempting and superficially plausible to interpret both events as expressions of the same general phenomenon.

But to state a truism: Mass society can be dehumanizing without its denizens being mass murderers. In his magisterial study Nazi Germany and the Jews Saul Friedländer describes the mentality of “redemptive anti-Semitism” that pervaded Nazi rule from its inception. What is needed to turn bureaucratic specialists into executioners is an ideological world view that underwrites racial supremacy and terror. This is the indispensable component that Nazism furnished and that, during the 1930s, reoriented Germany as a society hell-bent on military aggression, imperial expansion, and racial purification. One of the outstanding merits of Stangneth’s comprehensive account is that she shows that Eichmann was anything but a faceless cog in the machine. He fully subscribed to the ideological goals of the regime, including mass murder.

From the very beginning, Eichmann was a firm believer in the existence of a Jewish world conspiracy and thus fully partook of the murderous ethos so well described by Friedländer. In Eichmann’s view, the elimination of World Jewry, far from being a matter-of-fact, bureaucratic assignment, was a sacred duty. During one of Eichmann’s visits to Auschwitz, commandant Rudolf Höss confided that, upon seeing Jewish children herded into the gas chambers, his knees quivered, whereupon Eichmann rejoined that it was precisely the Jewish children who must be first sent into the gas chambers in order to ensure the wholesale elimination of the Jews as a race.

In a hastily contrived farewell speech to his subordinates at the end of the war, Eichmann declared that he would die happy, knowing that he was responsible for the deaths of millions of European Jews:

I will laugh when I leap into the grave because I have the feeling that I have killed 5,000,000 Jews. That gives me great satisfaction and gratification.

Twelve years later, in the course of the alcohol-infused colloquies with a group of fugitive Nazis in Buenos Aires whose transcripts are one of Stangneth’s key sources, he said: “To be frank with you, had we killed all of them, the thirteen million, I would be happy and say: ‘all right, we have destroyed an enemy.’”

To describe such a person as merely a man of “revolting stupidity” (von empörender Dummheit), as though his lack of intelligence somehow made his status as a genocidal murderer comprehensible, as Hannah Arendt did in the course of a 1964 interview, is perilously myopic. It was as though, by alluding to Eichmann’s purported intellectual failings, Arendt could make all other substantive questions and issues disappear. Perversely, the Jewish Specialist for the Reich Security Main Office ended up having the last laugh, hoodwinking Arendt into believing that he was little more than a bit player on a larger political stage. Yet, in the Jewish émigré press during the late 1930s (which Stangneth believes that Arendt had read), Eichmann had already been known as the “Tsar of the Jews” and was notorious for his brutality. But Arendt had her own intellectual agenda, and perhaps out of her misplaced loyalty to her former mentor and lover, Martin Heidegger, insisted on applying the Freiburg philosopher’s concept of “thoughtlessness” (Gedankenlosigkeit) to Eichmann. In doing so, she drastically underestimated the fanatical conviction that infused his actions.

By underestimating Eichmann’s intellect, Arendt also misjudged the magnitude of his criminality. Yet, as Stangneth demonstrates convincingly, in cities across the continent, Eichmann proved himself to be a persistent and effective negotiator, and when he failed to acquire what he demanded by way of negotiations, he was adept at using threats. Thus with a relatively small staff at his disposal, Eichmann systematically forced Jews out of their residences and into makeshift ghettos. As the Final Solution began, he arranged for their long-distance transport to the far reaches of provincial Poland, where the extermination camps lay in wait. As Raul Hilberg, on whose findings Arendt relied extensively, observed:

[Arendt] did not discern the pathways that Eichmann had found in the thicket of the German administrative machine for his unprecedented actions. She did not grasp the dimensions of his deed. There was no “banality” in this “evil.”

To amplify what she meant by the banality of evil, Arendt invoked the concept of “administrative murder,” which, in keeping with the robotic portrait she had painted of Eichmann, was another way of establishing the primacy of the functionary or desk murderer. But there had been nothing in the least “administrative” or “banal” about the barbaric mass shootings of the Einsatzgruppen—whose signature was the infamous Genickschuss (shot in the nape of the neck)—as led by the SS’s notorious “Death’s Head” brigades in the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. These deaths occurred prior to the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, in which the logistics of the Final Solution were outlined.

Eichmann’s organizational talents became especially vital and indispensable in the case of the deportation and extermination of 565,000 Hungarian Jews during the waning years of the war. The Hungarian situation was especially tricky. Even though the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising had been successfully and brutally suppressed by the SS, it had exposed a weakness in the Nazi machinery of extermination. In addition, the RSHA had failed in its attempts to deport Denmark’s meager total of less than 8,000 Jews. Following D-Day, it had become clear that, from a German standpoint, the war was unwinnable. Thereafter, numerous individual Nazi potentates sought to scale back the Jewish deportations in the hope of receiving favorable treatment from the soon-to-be-victorious Allies. But as Stangneth shows, Eichmann would have none of it. In fall 1944, he went so far as to defy Himmler’s order to halt the Hungarian deportations. Moreover, he played an especially insidious role in overseeing the “death marches” of the remaining Hungarian Jews (some 400,000 had already been transported to Auschwitz), under conditions that were indescribably brutal.

As Germany’s military situation began to deteriorate, Eichmann showed himself especially adept at ensuring that the gears of the killing machine remained well oiled. To characterize Eichmann as a “desk murderer” in order to downplay his convictions as a devoted SS officer who reported directly to Reinhard Heydrich and Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller is seriously misleading. After all, the duties of office demanded that Eichmann regularly visit various killing sites.

In 1998, an immense transcript of Eichmann’s conversations with Dutch collaborator and Waffen SS officer Willem Sassen from the late 1950s in Argentina was mysteriously deposited in the German Federal Archive in Koblenz. In those conversations, Eichmann told Sassen “When I reached the conclusion that it was necessary to do to the Jews what we did, I worked with the fanaticism a man can expect from himself.” He seems to have had in mind Heinrich Himmler’s statement of the requirements of total ideological commitment within the SS at the very height of the extermination process:

These measures in the Reich cannot be carried out by a police force made up solely of bureaucrats. … A corps that had merely sworn an oath of allegiance would not have the necessary strength. These measures could be borne and executed only by an extreme organization of fanatic and deeply convinced National Socialists. The SS regards itself as such and declares itself as such, and therefore has taken the task upon itself.

How Arendt could believe that someone like Eichmann could thrive in an organization whose raison d’être was mass murder, shorn of the ideological zeal described by Himmler, is difficult to fathom. Yet, time and again, in defiance of all evidence to the contrary, she maintained that Eichmann could best be described as a mere “functionary.” “I don’t believe that ideology played much of a role,” Arendt repeatedly insisted, “to me that appears to be decisive.”

In this respect, Arendt’s findings dovetailed with a general trend in accounts of the Holocaust that downplayed the role of individual perpetrators in favor of the impersonal “structures” of modern society. But white-collar workers and “organization men” do not as a matter of course commit mass murder unless they are in the grip of an all-encompassing, exterminatory world view, such as the Nazi credo that SS officers were obligated to internalize. As Walter Laqueur noted during the late 1990s: Arendt’s “concept of the ‘banality of evil’ . . . made it possible to put the blame for the mass murder at the door of all kind of middle level bureaucrats. The evildoer disappears, or becomes so banal as to be hardly worthy of our attention, and is replaced by . . . underlings with a bookkeeper mentality.”

In seeking to downplay the German specificity of the Final Solution by universalizing it, Arendt also strove to safeguard the honor of the highly educated German cultural milieu from which she herself hailed. A similar impetus underlay Arendt’s contention, in her contribution to the Festschrift for Heidegger’s 80th birthday, that Nazism was merely a “gutter-born phenomenon” and had nothing to do with the spiritual (geistige) questions of culture. In light of what we now know about the extent of educated German support for the regime (not to speak of what we know about Heidegger, on which see my earlier essay “National Socialism, World Jewry, and the History of Being: Heidegger’s Black Notebooks” in this magazine) Arendt’s notion that Nazism has nothing to do with the “language of the humanities and the history of ideas” appears naïve.

In retrospect, Arendt’s application of Heidegger’s concept of “thoughtlessness” to Eichmann and his ilk seems to have been intended to absolve the German intellectual traditions. Even Arendt’s otherwise stalwart champion, Mary McCarthy, pointed out the crucial differences between the English word “thoughtlessness,” which suggests a boorish absent-mindedness, and the German Gedankenlosigkeit, which literally indicates an inability to think.

At the height of his danse macabre before the judicial tribunal in Jerusalem, Eichmann went so far as to characterize himself as a “Zionist,” on the basis of his negotiations during the 1930s with Jewish officials over the emigration of Viennese and Czech Jews. For her part, Arendt seemed to buy Eichmann’s self-serving self-description wholesale. Yet, as Stangneth shows, these forced emigrations organized by Eichmann were unfailingly sadistic and brutal. In retrospect, they were, in fact, a trial run for the Europe-wide Jewish deportations that culminated in the Final Solution. Thus under Eichmann’s supervision and under the cover of “emigration,” Jews were divested of their homes, their life savings, their possessions, their livelihood, and their citizenship in exchange for the uncertainties and ignominies of forced exile.

That Eichmann smugly viewed his indispensable role in the Final Solution as a crowning achievement was an opinion he expressed on numerous occasions. British historian David Cesarani aptly describes the RSHA Nazi’s Specialist for Jewish Affairs as acting “in the spirit of a fanatical anti-Semite who is locked in a world of fantasy,” a description that historian Christopher Browning recently seconded, noting that, “Eichmann embraced a worldview that was delusional and ‘phantasmagoric’ in its belief in a world Jewish conspiracy that was the implacable and life-threatening enemy of Germany.” When the regime imploded in May 1945, he became a warrior-without-a-cause.

As Stangneth shows, during his Argentine exile, Eichmann and his Nazi comrades harbored delusions of the Reich’s return. At the time, one of Eichmann’s pet literary projects was the drafting of an “open letter” to Konrad Adenauer that was intended to justify the National Socialist state and its aims. In Eichmann’s view, the Federal Republic should have stopped issuing apologies since it had nothing to be ashamed of. After all, during the war, Germany had been involved in a life-or-death struggle in which it had been necessary to employ all of the means at its disposal. As Eichmann was fond of saying: “Krieg ist Krieg”—war is war.

In Buenos Aires, the Sassen clique published a neo-Nazi journal, one of whose main aims was to burnish the reputation of the Third Reich in the face of “calumnious accusations” on the part of World Jewry. Foremost among those purported “calumnies” was the so-called “Auschwitz lie”: the “myth” that the Third Reich had been responsible for the deaths of six million Jews. It was for this reason that, in 1956, the former Dutch SS officer Willem Sassen conducted a series of interviews with Eichmann. After all, there could be no more convincing witness than Eichmann, who, from his perch at RSHA headquarters in Berlin, had dutifully and conscientiously organized the entire affair.

Yet along the way, Sassen and company encountered a stumbling block. On the one hand, Eichmann being Eichmann, he was more than willing to relive in minute detail his halcyon days in Division IV B of the Reich Security Main Office. The problem was that the destruction of European Jewry had been Eichmann’s proudest achievement.

By the end of the taping sessions, the mismatch between Sassen’s revisionist goals and Eichmann’s compulsive braggadocio reached absurd proportions. The misunderstanding culminated in a raucous 1957 meeting at which Eichmann felt compelled to provide a final statement to all assembled of his mature ideological world view. Here are three salient passages from Eichmann’s final declaration to Sassen and company:

I must throw all caution to the wind and tell you that, before my Volk goes to ruin and bites the dust, the whole world should go to ruin and bite the dust—my Volk, only thereafter!

I say to you honestly as we conclude our sessions, I was the “conscientious bureaucrat,” I was that indeed. But I would hereby like to expand on the idea of the “conscientious bureaucrat,” perhaps to my discredit. Within the soul of this conscientious bureaucrat lay a fanatical warrior for the freedom of the race from which I stem . . . I was manifestly a conscientious bureaucrat, but one who was driven by inspiration: what my Volk requires and my Volk demands is for me a holy commandment and a holy law. Jawohl!

But now let me tell you, since we are almost at the end of this entire outburst [Platzen] . . . : I regret nothing! I will never crawl my way to the cross! . . . That is something I cannot do . . . because my inner self bridles at the thought that we did something wrong. No, I say to you quite honestly, had we killed 10.3 million Jews out of the 10.3 million we had in our sights, I would be quite satisfied, and would say that we annihilated an enemy . . . We would have fulfilled our mission, for our race and our Volk and for the freedom of nations, had we exterminated the cleverest spirit among the spirited peoples alive today. For that is what I told [Julius] Streicher, and what I have always preached: we are fighting against an opponent who, as a result of thousands of years of practice and experience, is cleverer than we are . . .

These are the words not of a “desk murderer” but of a convinced Nazi. They represent a toxic admixture of crude social Darwinism, malicious half-truths, and ideological distortions. The highest reality is that of the volk. Weak peoples perish. The strong survive. All pretensions of international law to the contrary, it is the survival of the fittest that determines the “law of peoples.” Since, as with all of life, the goal of nations is self-preservation, it is permissible to utilize all the means at one’s disposal to attain this end. Any volk that ignores this imperative is doomed to extinction. Universal morality—Biblical injunctions (“Thou shalt not kill,” “Love thy neighbor as thyself”), Kant’s categorical imperative, democratic pretensions to universal equality—must be emphatically rejected insofar as such effete considerations expose a people to anti-völkisch precepts and constraints that threaten to sap its lifeblood, its will to survive. To cite Nietzsche, whose influence Eichmann at various points acknowledged, moral considerations that transcend a volk’s drive to self-preservation are symptomatic of a “slave morality.” If nature has decreed that life is in essence a fight to the death for racial supremacy, what sense does it make to buck this trend?

In Eichmann’s view, one of the reasons why the Jews, those consummate cosmopolitans, are so dangerous is that, as a people without roots, they subsist and persevere entirely at the expense of other peoples. For this reason, they are the sworn racial enemy of the Germans as well as of all peoples. Hence, the National Socialist Vernichtungskrieg (war of annihilation) against the Jews was, on racial grounds, entirely justified.

Insofar as they are impervious to reason and reality, such mythological world views are self-perpetuating. The clan of believers has a vested interest in maintaining the illusion that the world view is entirely coherent and functional, since there is really no fallback position. Nazi ideology was an all-enveloping proposition. It only collapsed when, at the war’s end, the major German cities lay in ruins and Germany had become, following Hitler’s suicide, a führerlose Gesellschaft: a society without a leader. It is therefore difficult to understand how, shortly after the trial, Arendt, speaking of Eichmann’s actions and conduct, could assert, “I don’t think that ideology played any role.” A decade earlier, the chapters on “Ideology” and “Race” had been among Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism’s genuine strong points.

If ever there was a “trial of the 20th century,” the Eichmann trial was it. In Europe and North America, the meaning of the trial, and thus to a great extent the Holocaust itself, was filtered through the lens of Arendt’s popular account and the contentious debate that it spawned. Her provocative subtitle, the “banality of evil,” helped establish the so-called “functionalist” interpretation of the Holocaust, in which the role of obedient desk murderers and mindless functionaries assumed pride of place, producing a Holocaust strangely divested of anti-Semitism. The reductio ad absurdum of this approach may have finally come during the controversy over Daniel Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. In the course of this debate, in the 1990s, Hans Mommsen, by then the recognized dean of German Third Reich scholars, said, “I don’t think the perpetrators were really clear in their own minds about what they were doing when they were engaged in killing Jews.” Mommsen’s avowal was widely viewed as an index of how far out of touch professional historians were with the German public’s need for clarity and for an honest accounting of a previous generation’s horrific transgressions. In retrospect, Arendt’s stress on the perpetrators’ lack of animosity toward the Jews harmonized with the post-war German political agenda of parrying questions of historical responsibility. Although Arendt did not necessarily share this agenda, her correspondence reveals how sensitive she was to the tendency to equate “Germans” with “Nazis.”

Although Arendt’s interpretive approach, as well as the functionalist paradigm in general, identified a set of important socio-historical concerns, it also downplayed the uniqueness of the Shoah by inserting it within an overarching narrative that highlighted the dangers of “modernity,” “mass society,” “atomization,” and so on. The Holocaust came to symbolize the risks of the transition from traditional society to the modern administrative state. But in the end this German Sociology 101 “from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft” approach failed to explain the historical uniqueness of the radical evil that was Nazi Germany. Here, one of the unexplained paradoxes and ironies was that in The Origins of Totalitarianism the figure of radical evil occupied pride of place in Arendt’s interpretive scheme. In fact, she concluded the book’s Preface by declaring: “if it is true that in the final stages of totalitarianism an absolute evil appears (absolute because it can no longer be deduced from humanly comprehensible motives), it is also true that without it we might never have known the truly radical nature of Evil.”

As Bettina Stangneth reminds us repeatedly in Eichmann Before Jerusalem, when Hannah Arendt traveled to Jerusalem to cover the Eichmann trial, part of the baggage she carried was a fixed set of socio-historical predispositions and prejudgments. Nowhere was this problem more evident than in her attempt to understand Eichmann’s conduct in terms of the misguided figure of the “banality of evil.” What should have been clear then and should certainly be clear now is that if the Holocaust was banal, then it was not evil. And if it was evil—as it indubitably was—then it was not banal.

Editor’s Note:

Richard Wolin’s review of Bettina Stangneth’s book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Hannah Arendt and the banality (or not) of evil. Yale Professor Seyla Benhabib responded in a New York Times piece, others blogged, and Wolin responded in an essay on our website. Now Professor Benhabib has rejoined the debate and Professor Wolin has replied a final time. Here’s a guide to the exchange from the original review to its last installment.

- The Banality of Evil: The Demise of a

Legend by Richard Wolin

Bettina Stangneth’s newly translated book Eichmann Before Jerusalem finally and completely undermines Hannah Arendt’s famous “banality of evil” thesis. - Who’s on Trial, Eichmann or Arendt? by Seyla Benhabib

On September 21, 2014, on The New York Time’s website, Seyla Benhabib argued that a “rejection of the ‘banality of evil’ argument . . . does not hold up” and took issue with Wolin’s review. - Thoughtlessness Revisited: A Response

to Seyla Benhabib by Richard

Wolin

Richard Wolin responds to Benhabib’s “ringing reaffirmation of Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil.”

- Richard Wolin on Arendt’s “Banality of Evil” Thesis by

Seyla Benhabib

Seyla Benhabib rejoins the debate, contesting Wolin’s critique of Arendt’s banality thesis on historical and philosophical grounds. - Arendt, Banality, and Benhabib: A Final Rejoinder by

Richard Wolin

In the final installment of the exchange, Wolin defends and amplifies his critique.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

How the Baby Got Its Philtrum

The idea of learning as a recovery of what we once possessed is what makes Bogart’s bubbe mayse, and ours, so memorable: We can all touch that little hollow and feel the impress of forgotten knowledge.

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

Biblical Start-Ups

A prominent Israeli novelist on novelties in the Bible.

Miami Vices

As it is, The Orchard reads more like Days of Our Lives than Daniel Deronda.

digbydolben

This entire article is really an effort to dismiss the “collective guilt” of ANY people, and its tacit agenda is actually to contribute to the denial of the “collective guilt” of the present-day Israeli populace for the ethnocide they are conducting against the Palestinians; for, if Hannah Arendt’s condemnation of Eichman for being a mere bureaucratic “cog” in the Nazi killing machine—which the author disingenuously pretends to be an exculpation of him—can be dismissed, then so can the participation of any large majority of people in collective participation in their leadership’s oppression—and now we are speaking, by implication, of what the Israelis are doing to the Palestinians, as well as what the Americans and British have done to Muslim populations all over the Middle East.

Our sly pro-Zionist author says this: “…again and again, one sees how readily Arendt blurred the line between victims and executioners,” when what Arendt was trying to say is that there is ALWAYS in such situations, a “blurring” of those lines, when one is speaking of so tragic an event as a CULTURALLY constructed alibi for genocide. Indeed, what people have NEVER been historically complicit in the genocide of SOMEBODY’S tribe? The profound philosopher Arendt wanted Eichmann to stand, in her tome, for the collective guilt, not only of the ordinary German people, but of the American people and the British people, whose leaders refused, with the tacit assent of the folks they led, to bomb the train lines running to the concentration camps. Eichmann, in her tome, is a symbol--but he’s a very good symbol—for the murderous nature of the modern bureaucratized State.

Our Zionist author, with his probable agenda of excusal of the ethnocide of Palestinians and his determination to affirm the almost-numinous quality of the Shoah, quotes Arendt thusly:

“…[Eichmann] reinvented himself at every stage of his life, for each new audience and every new alarm.” He becomes ‘subordinate, superior officer, perpetrator, fugitive, exile, and defendant’”

--in effect, denying that she means that this is the nature of EVERY “cog” that works subserviently to the modern bureaucracy of State-terrorism—including the present-day one in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, which evicts and ethnically-cleanses Palestinians with a bloodless lack of conscience or empathy. It also characterizes the servants of the Obama regime, who justify the murder of young American teenagers, by saying they “should have chosen a different father” than the pro-jihadist who had sent his son to live with a grandfather, to keep him out of the harm’s way of the American drone that murdered him.

The writer apparently does NOT WANT to understand that the description of “the meek and unassuming Argentine rabbit breeder who took the witness stand in Jerusalem and described himself as ‘a small cog in Adolf Hitler’s extermination machine’” is a powerful indictment of what is now a very large class of those who “stand by and do NOTHING” to interfere with the murderous designs of the large modern class of sociopathic demagogues. Hitler is EVERYWHERE nowadays, doing his Satanic work, and all of us pretend not to notice his existence by insisting that the Shoah was unique and that Germans like Eichmann helped to plan it; that’s a lie; they did NOT—instead, they, like the rest of us, did something even worse, from the standpoint of Arendt’s and Heidegger’s existentialist ethic: they stood by and let it happen, in Germany, just like modern Israelis are permitting their country, once the hope of liberal, pluralist democracy in the Middle East, to be turned into an apartheid state.

And here’s the fundamental deception, at the heart of this article: “…mass society can be dehumanizing without its denizens being mass murderers…” because it is impossible to become complicit in “mass murder” without at first becoming “dehumanized.” We, in the modern “inverted totalitarianisms” of perverted democracies such as the American, the Israeli, and many others, are becoming dehumanized by sociopathic demagogues, so that they CAN make us complicit in the mass murders that further their economic and political agendas. This is what the spiritual prophets of the world, such as the Dalai Lama and Pope Francis, are trying to tell the brainwashed sheep-people of the First World, over the strident voices of the Obamas, the Clintons, the McCains and the Netanyahus.

Our author writes this: “…from the very beginning, Eichmann was a firm believer in the existence of a Jewish world conspiracy…” and to that I say “So what? Is that so different from modern believers in Muslim ‘world conspiracy,’ or ‘banksters’’ ‘world conspiracy,’ Why do you wish to render the Shoah unique in our minds? Do you actually WISH to turn our attention away from what is a modern catastrophe in the realm of ethics and morality?”

And, so, our author quotes Eichmann, to chilling effect:

“In a hastily contrived farewell speech to his subordinates at the end of the war, Eichmann declared that he would die happy, knowing that he was responsible for the deaths of millions of European Jews:

I will laugh when I leap into the grave because I have the feeling that I have killed 5,000,000 Jews. That gives me great satisfaction and gratification.”

How can he not appreciate that this is a mere resurgence of something that Judaeo-Christian civilization had ATTEMPTED to eradicate, but has obviously failed to do so? Doesn’t he know that Alexander the Great would have said the same thing about the two thousand he crucified after taking Tyre? Doesn’t he know that the Mongol Genghiz Khan would have said the same about the millions he slaughtered of the Abbasid Caliphate? There is nothing unique about Eichmann’s vicious human nature.It IS "banal," in the sense that it is ever-potential in all of us.

Although I do agree with the author that Eichmann was especially ferocious in his application of the “Final Solution” of the “problem of the Jews,” and note the author’s apt description of his exemplary criminality:

“…Stangneth shows, Eichmann would have none of it. In fall 1944, he went so far as to defy Himmler’s order to halt the Hungarian deportations. [Proof of this act, and this act alone, the author forgets, is what won the conviction in Jerusalem; it’s the key to the great film about the trial] Moreover, he played an especially insidious role in overseeing the “death marches” of the remaining Hungarian Jews (some 400,000 had already been transported to Auschwitz), under conditions that were indescribably brutal.”

…I would also insist that, if Arendt had been writing about almost any other “cog” in the Nazis’ machinery of mass-murder, she would have been absolutely correct about the “banality” of their “evil,” and it is her insistence on the complicity of moderns in the crimes of their bureaucratized state-systems that the author, it seems to me, wishes to dismiss—probably, I should like to insist, to gain sympathy for the “dehumanization” of modern Israeli “mass society.” Notice, as evidence of this bias, the author’s cunning suppression of the Zionist organizations’ complicity in what he describes as Eichmann’s “trial run” for mass extermination:

“In retrospect, they were, in fact, a trial run for the Europe-wide Jewish deportations that culminated in the Final Solution. Thus under Eichmann’s supervision and under the cover of “emigration,” Jews were divested of their homes, their life savings, their possessions, their livelihood, and their citizenship in exchange for the uncertainties and ignominies of forced exile.”

I would suggest that he and his supportive readership here go even to Wikipedia, and type in the words “Transfer Agreement.”

russedav

What author Wolin and commentor digbydolben are both oblivious to is the Biblical reality of the true history of a world where Adam fell in the Garden of Eden and his Original Sin was agreeing with satan's "Did God say?" that they and the Nazis & the Jews alike have joined in reiterating countless times over the course of the world's 6,000 year history

(only scientifically ignorant, morally bankrupt antiChristian bigotry vainly opines the asinine "millions/billions of years" nonsense extensively refuted by reputable science (vs the vast lawless, fascist majority still in league with fascism, like East Anglia's "global warming" scam done for $ sex & power as usual), seen at www.creation.com).

It's strange how though the cowardly bullies the Jews cried out vehemently "His blood be on us and on our children" (Matthew 27:25) before they had their Messiah Jesus they rejected (stopping their ears to His Truth lest it convict their hearts of their sin as we still do today) executed instead of the murderer Barabbas (Matthew 27:21), when it comes around to it they quickly move to push it away from themselves, pretty much like the cowardly bullies the Nazis did, seen in their cruel shunning and mock funerals of family members who convert to the Christian faith and assault and battery of Christian missionaries hypocritically reflective of the very evils of fascism they pretend to decry unless doing so themselves. There was only One perfect Man in this world, Jesus Christ, and He had to be crucified, as we would do today, and continually do in and with the Kermit Gosnells of this world we adore, like Pilate fervently continually washing our hands in vain to rid them of His blood stains for which we are forever guilty and condemned and terrorized eternally in hell unless receiving for ourselves the very Blood He shed for our salvation and redemption. God save us! See www.desiringGod.org for how to receive His salvation and redemption and ultimate shalom. Soli Deo gloria!

Princess

Unfortunately, there are a breed of journalists like Arendt who have their story written prior to investigation and research. Certainly an architect of such a grand killing scheme cannot be stupid, but is rather brilliant in evil. However, these require the cooperation of mindless cogs to implement their plans. Perhaps Arendt was not cognizant of her own self-protective mechanisms?

The Israeli film, "The Flat," touches on a more complex situation, that of the German who hired Eichmann, whose family had a close friendship with a Jewish family that picked up following the war as if nothing happened. While "everyman," is not likely in danger of becoming and Eichmann, I suspect most of my neighbors and colleagues could easily become cogs.

It is getting wearying that the antisemites come out of the woodwork and find a way to turn every article involving Jews or Israel into a an opportunity to spew their propaganda. That they are permitted to squat on the blogs of others with their tomes is a bit much.

heidigeorge

As much as I would like to use this space to respond to commenter digbydolben, I will stick to my intention to post a comment about my decades old revulsion at the phrase the "banality of evil." I'd like to parse definitions to explain why I find Arendt's phrase not only offensive and wrong, but frankly, unfathomable when attached to any attempt to comprehend Eichmann's role in the Shoah.

Here is what I found to be a comprehensive definition of the noun

"banality": "unoriginal, boring, trite, vapid, unimaginative, stale, prosaic, and dull." When I think of (and use) the word "banality," implicit in my understanding and usage is a sense and feeling of passivity. Conversely, the word "evil" suggests activity, energy, purpose, and intention. When, if ever, did Arendt try to justify to herself or to us the creation of what is, ipso facto, a linguistic impossibility? To coin a phrase to describe the monstrous activity of mass murderer Eichmann deserves every bit of the scorn we heaped upon her.

I am happy to learn Bettina Stangneth has written a refutation of this harmful (yes, harmful!) phrase, and I thank Richard Wolin for his wide ranging and learned article.

Michael Selzer

Hannah Arendt sought to buttress her bizarre view of Eichmann as a banal person by claiming that a number of Israeli psychiatrists or psychologists had evaluated Eichmann and determined that he was "normal". In our book, "The Nuremberg Mind" (Quadrangle, 19778) Florence Miale showed that Dr Kulcsar, appointed to the task by the Israeli police, was the only psychologist or psychiatrist to examine Eichmann and that he found him to be anything but a normal person. Kulcsar sent Eichmann's responses to the Szondi test to Dr Szondi, though without identifying the person, and Szondi reported that in his long career he had never encountered a person with as strong a murderous drive as the one who had produced the responses he had received from Kulcsar.

The view of Eichmann as a thoroughly dangerous character disturbed those who, like Stanley Milgram, were committed to a liberal view of evil as a regrettable social malfunction; nevertheless, this view - that Eichmann was anything but a "banal" person - is very well grounded. A much more challenging question, it seems to me, is what prompted Hannah Arendt to lie so crudely and maliciously. Very possibly, her notorious affairs with the Nazi Heidigger provide part of the answer...

Jacob Arnon

Please explain why you would post the lunatic antisemitic ravings of a "digby dolben?

"Our Zionist author, with his probable agenda of excusal of the ethnocide of Palestinians and his determination to affirm the almost-numinous quality of the Shoah, quotes Arendt thusly:

How does this comment enlighten us about the masterly review of Bettina Stangneth new study?

I suggest you spend a few minutes reading submitted comments to make sure they address the topic at hand.

drj

First of all, kudos to Wolin for his superb explication of how Arendt's Weltanschauung motivated her to construct such a distorted, apologist, and fundamentally dishonest characterization of the motivation of Eichmann and his merry band of murderers in charge of The Final Solution.

I was stunned to read the rambling assault by 1 "Digbydolen Wolin's inarguably perceptive, honest and accurate insights into how fatally flawed and misleading Arend's theses were. The wild racist accusations about "Palestinian genocide" are so dishonest, distorted, and wildly out of touch with reality, that 1 can safely assume that this commenter is afflicted with the world's oldest prejudice. How Israel, which in fact is the ONLY Mideast country which permits free expression, practice of all religions, and full respect for human rights of all, can be accused of "ethnocide" by attempting to defend itself against the relentless attacks by Islamofascists motivated only by goals of Israel's extinction is obscenely and offensively absurd.

And further to invoke the Holocaust and the inarguable collective guilt owned by a well-described enabling German society with the pluralistic, fair-minded and amazingly tolerant Israeli population is a slander so obnoxious and mendacious that it could only be motivated by very deep-seated antisemitic racism. His labored attempts to discredit Wolin's extremely well-thought out and cogent analysis reveal only a very troubled, hateful and repulsive mindset of deeply embedded racist bias.

The only "ethnocide" going on the Mideast is the never ending attempts by the region's numerous Islamofascist groups to do exactly what Hamas' charter and Iran's leaders have explicitly declared they want to do--wipe Israel off the face of the Earth.

To try contorting the truth and inverting the real blame for Mideast conflict and somehow try to portray courageous, determined, and extremely fair-minded peace-loving Israel with its savage and primitive enemies is a disgusting transmogrification of reality and morality.

"Digbydolben"'s comments show sadly only 1 thing: how durable and deep-seated is the nature of antiSemitism, and the contemptible individuals who continue to purvey the worst kind of lies in its service. I can only hope that this individual obtains the psychiatric care he so obviously requires.

apologues

Last November 26, 2013, Rivka Galchen made, in The New York Times, the definitive statement about the ginned-up "controversy" over Hannah Arendt's picture of Adolf Eichmann: "Arendt does not argue that the Holocaust and its unspeakable horrors are banal. She does not endorse or believe Eichmann’s presentation of himself as a man beset by the tricky virtue of obedience. And she does not say that the evil she saw in Eichmann is the only kind of evil. Many of the objections to her work are based on arguments never made."

Richard Wolin has so misrepresented the contents of Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem" that the only question is whether he does so consciously and maliciously. The answer is yes, but even more devastating that his malice are his failures of understanding. It would take too long to refute them one by one, but for careful readers of Arendt, these hints may suffice. First, the banality she referred to was Eichmann's mind, never his deed; and this banality was perfectly consistent with fanatical devotion to Hitler. (This was Eichmann's true loyalty, to the corporal from the working class who rose to head the nation, and this loyalty is the reason that Eichmann continued to transport Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in defiance of Himmler.) Second, "the banality of evil" does not contradict Arendt's earlier classic picture of "radical evil," it fulfills it. (Her later renunciation of the term "radical evil" was a philosopher's quibble: she still spoke of "extreme evil" and continued to see the Nazi genocide as an unparalleled crime in world history.) Third, there is a difference between a raving anti-Semite like Julius Streicher, who joins the party to fulfill his fanatical ideology, and a careerist like Eichmann, who joins the party hoping to eventually rise to full colonel, and signs up for the ideology as the necessary prerequisite. Arendt understood that Eichmann was completely on board with the party's program. She was interested in Eichmann's psychology, and she thought, correctly, that it differed markedly from Streicher's. Fourth, the notion that she tried to make the Jews more complicit in their own fate while letting the perpetrators off the hook is mere calumny and will be filed under the head of Character Assassination by anyone who bothers to read what she actually said and then remembers that a negative view of some of the Jewish council heads was so pervasive in Israel that Arendt would have been journalistically derelict to fail to mention it.

Wolin provides strong evidence for precisely the banality of evil by spending several paragraphs describing the Nazi belief in the Jewish world conspiracy: he correctly characterizes this belief as "impervious to reason and reality." What could be more banal than to surrender your own connection to reality and take all your ideas from those of a deranged and murderous mythographer? What is more banal than the anti-Semitic myth itself? Again: there was nothing banal about the genocide that was attempted on behalf of this world-view; but no morally sane person, and certainly not Arendt, has ever said there was.

Does Wolin deliberately mis-lead his readers? You decide.

The quote by Eichmann, that "I will laugh when I leap into the grave because I have the feeling that I have killed 5,000,000 Jews," appears in Arendt's text. A reader can disagree with how she chooses to fit it to her interpretation of Eichmann's psychology, but it is foolish to pretend that new information has come to light proving that she was duped.

Wolin quotes from the correspondence between Gershom Scholem and Arendt, but neglects to give any of her dignified response. Wolin must know that Scholem, too, complained that she was taken in by Eichmann's claim to be a Zionist. She responded as follows: "I never made Eichmann out to be a 'Zionist.' If you missed the irony of the sentence – which was plainly in oratio obliqua, reporting Eichmann's own words – I really can't help it." Wolin might be excused for in hastily making the same mistake that Scholem made, if we did not know that he must surely have read Arendt's answer to Scholem. But the error itself is indicative. Just as Arendt did not believe she needed to spell out the horror of the Holocaust, the impossible predicament of the Jewish councils in trying to save their communities, and the obvious commitment of all SS officers to the Nazi program, she did not think she needed to supply her own horse laugh at Eichmann's absurd claim to be a Zionist. But there she was indeed mistaken. Readers like Wolin need to be led by the hand.

Wolin contradicts himself by first arguing that Eichmann fooled Arendt with his harmless rabbit breeder act, but later agreeing with Stangneth that Eichmann made a "last stand" on behalf of Nazi values. It is interesting to see Stangneth, and Wolin, try to rehabilitate Eichmann as a formidable intellect. Really? Arendt mentions in her book that Eichmann gave a coherent layman's account of Kant's categorical imperative, but suffice it to say that she considered it laughable to take seriously Eichmann's attempt to give a moral gloss to his activities as a mass murderer. But Stangneth goes so far as to write in her book that "Eichmann, as the records from Israel show, was capable of powerful arguments." Really? Do we want to say that there may be something to the Anti-Semitic Theory of Everything after all? – that, at least, "powerful arguments" can be brought to bear on its behalf? Or would we do better to agree with Arendt that Eichmann was so captivated by his hero Hitler and so in thrall to what his superiors told him that he could safely be said to be almost incapable of meaningful thought?

The shortest way home here may be to state clearly and unequivocally that Eichmann was a moral imbecile. By his own account, he did not feel guilt when he sent unoffending men, women, and children completely unknown to him to be murdered by the millions; but he would have felt guilt had he disobeyed a lawful order (and the obscenity of the Third Reich is that the orders were all lawful). Arendt began the book assuming that what I have just said would be contradicted by no one, so she thought there was no need to harp on it; she ended it with a strong piece of rhetoric justifying the decision to execute Eichmann. She did not think moral imbecility was any excuse, however much the unimpressive defendant labored to make the court believe that he came by it honestly.

But the continued campaign against Arendt herself – who made a study of anti-Semitism before Hitler even took power, worked for Zionist organizations, was twice detained by the Nazis, and would have been shipped to a death camp had she not escaped the camp in France and fled to America – and to base it on the libel that she went easy on the perpetrators of the Holocaust, is grist for another mill. There are many shades of banality.

chaerophon

"What first undermines and then kills political communities is loss of power and final impotence; and power cannot be stored up and kept in reserve for emergencies, like the instruments of violence, but exists only in its actualization. Where power is not actualized it passes away and history is full of examples that the greatest material riches cannot compensate for this loss. Power is actualized only where word and deed have not parted company, where words are not empty and deeds are not brutal, where words are not used to veil intentions but to disclose realities, and deeds are not used to violate and destroy but to establish relations and create new realities." Hannah Arendt

Thoughtlessness is powerlessness and thus is a condition of inhumanity regardless of the sophistication of its presentation.

Personal animus whether it is directed at Eichmann or Cecile Richards does not address the population organized travesties of the systems under their supervision

apologues

Last November 26, 2013, Rivka Galchen made, in The New York Times, the definitive statement about the ginned-up "controversy" over Hannah Arendt's picture of Adolf Eichmann: "Arendt does not argue that the Holocaust and its unspeakable horrors are banal. She does not endorse or believe Eichmann’s presentation of himself as a man beset by the tricky virtue of obedience. And she does not say that the evil she saw in Eichmann is the only kind of evil. Many of the objections to her work are based on arguments never made."

Richard Wolin has so misrepresented the contents of Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem" that the only question is whether he does so consciously and maliciously. The answer is yes, but even more devastating than his malice are his failures of understanding. It would take too long to refute them one by one, but for careful readers of Arendt, these hints may suffice. First, the banality she referred to was Eichmann's mind, never his deed; and this banality was perfectly consistent with fanatical devotion to Hitler. (This was Eichmann's true loyalty, to the corporal from the working class who rose to head the nation, and this loyalty is the reason that Eichmann continued to transport Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in defiance of Himmler.) Second, "the banality of evil" does not contradict Arendt's earlier classic picture of "radical evil," it fulfills it. (Her later renunciation of the term "radical evil" was a philosopher's quibble: she still spoke of "extreme evil" and continued to see the Nazi genocide as an unparalleled crime in world history.) Third, there is a difference between a raving anti-Semite like Julius Streicher, who joins the party to fulfill his fanatical ideology, and a careerist like Eichmann, who joins the party hoping to eventually rise to full colonel, and signs up for the ideology as the necessary prerequisite. Arendt understood that Eichmann was completely on board with the party's program. She was interested in Eichmann's psychology, and she thought, correctly, that it differed markedly from Streicher's. Fourth, the notion that she tried to make the Jews more complicit in their own fate while letting the perpetrators off the hook is mere calumny and will be filed under the head of Character Assassination by anyone who bothers to read what she actually said and then remembers that a negative view of some of the Jewish council heads was so pervasive in Israel that Arendt would have been journalistically derelict to fail to mention it.

Wolin provides strong evidence for precisely the banality of evil by spending several paragraphs describing the Nazi belief in the Jewish world conspiracy: he correctly characterizes this belief as "impervious to reason and reality." What could be more banal than to surrender your own connection to reality and take all your ideas from those of a deranged and murderous mythographer? What is more banal than the anti-Semitic myth itself? Again: there was nothing banal about the genocide that was attempted on behalf of this world-view; but no morally sane person, and certainly not Arendt, has ever said there was.

Does Wolin deliberately mis-lead his readers? You decide.

The quote by Eichmann, that "I will laugh when I leap into the grave because I have the feeling that I have killed 5,000,000 Jews," appears in Arendt's text. A reader can disagree with how she chooses to fit it to her interpretation of Eichmann's psychology, but it is foolish to pretend that new information has come to light proving that she was duped.

Wolin quotes from the correspondence between Gershom Scholem and Arendt, but neglects to give any of her dignified response. Wolin must know that Scholem, too, complained that she was taken in by Eichmann's claim to be a Zionist. She responded as follows: "I never made Eichmann out to be a 'Zionist.' If you missed the irony of the sentence – which was plainly in oratio obliqua, reporting Eichmann's own words – I really can't help it." Wolin might be excused for hastily making the same mistake that Scholem made, if we did not know that he must surely have read Arendt's answer to Scholem. But the error itself is indicative. Just as Arendt did not believe she needed to spell out the horror of the Holocaust, the impossible predicament of the Jewish councils in trying to save their communities, and the obvious commitment of all SS officers to the Nazi program, she did not think she needed to supply her own horse laugh at Eichmann's absurd claim to be a Zionist. But there she was indeed mistaken. Readers like Wolin need to be led by the hand.

Wolin contradicts himself by first arguing that Eichmann fooled Arendt with his harmless rabbit breeder act, but later agreeing with Stangneth that Eichmann made a "last stand" on behalf of Nazi values. It is interesting to see Stangneth, and Wolin, try to rehabilitate Eichmann as a formidable intellect. Really? Arendt mentions in her book that Eichmann gave a coherent layman's account of Kant's categorical imperative, but suffice it to say that she considered it laughable to take seriously Eichmann's attempt to give a moral gloss to his activities as a mass murderer. But Stangneth goes so far as to write in her book that "Eichmann, as the records from Israel show, was capable of powerful arguments." Really? Do we want to say that there may be something to the Anti-Semitic Theory of Everything after all? – that, at least, "powerful arguments" can be brought to bear on its behalf? Or would we do better to agree with Arendt that Eichmann was so captivated by his hero Hitler and so in thrall to what his superiors told him that he could safely be said to be almost incapable of meaningful thought?

The shortest way home here may be to state clearly and unequivocally that Eichmann was a moral imbecile. By his own account, he did not feel guilt when he sent unoffending men, women, and children completely unknown to him to be murdered by the millions; but he would have felt guilt had he disobeyed a lawful order (and the obscenity of the Third Reich is that the orders were all lawful). Arendt began the book assuming that what I have just said would be contradicted by no one, so she thought there was no need to harp on it; she ended it with a strong piece of rhetoric justifying the decision to execute Eichmann. She did not think moral imbecility was any excuse, however much the unimpressive defendant labored to make the court believe that he came by it honestly.

But to continue the campaign against Arendt herself – who made a study of anti-Semitism before Hitler even took power, worked for Zionist organizations, was twice detained by the Nazis, and would have been shipped to a death camp had she not escaped the camp in France and fled to America – and to base it on the libel that she went easy on the perpetrators of the Holocaust, is grist for another mill. There are many shades of banality.

witheo

On the question of the banality of evil. On the question of the calculated, deliberate, systematic, methodical, scientifically efficient, mass extermination of anonymous, dehumanised, non-combatant fellow human beings. On an industrial scale that truly beggars belief. In our own lifetime. Do you have children? And preferably from a safely dehumanised distance. Away from the searing heat. The blisters. And the screams. The little children …

By the way. What follows is not German evil. Or Nazi evil. Or American evil. Or Military-Industrial Complex evil. Or born-again Christian evil. What kind of person does it take to do these everyday banal things? Have you got access to a bathroom mirror? Go take a look. You won’t like what you see.

Firebombing is a bombing technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs.

Although simple incendiary bombs have been used to destroy buildings since the start of gunpowder warfare, World War II saw the first use of strategic bombing from the air to destroy the ability of the enemy to wage war.

The Chinese wartime capital of Chongqing was firebombed by the Japanese starting in early 1939. London, Coventry, and many other British cities were firebombed during the Blitz. Most large German cities were extensively firebombed starting in 1942, and almost all large Japanese cities were firebombed during the last six months of World War II.

This technique makes use of small incendiary bombs (possibly delivered by a cluster bomb such as the Molotov bread basket). If a fire catches, it could spread, taking in adjacent buildings that would have been largely unaffected by a high explosive bomb. This is a more effective use of the payload that a bomber could carry.

The use of incendiaries alone does not generally start uncontrollable fires where the targets are roofed with nonflammable materials such as tiles or slates. The use of a mixture of bombers carrying high explosive bombs, such as the British blockbuster bombs, which blew out windows and roofs and exposed the interior of buildings to the incendiary bombs, are much more effective. Alternatively, a preliminary bombing with conventional bombs can be followed by subsequent attacks by incendiary carrying bombers.

The development of the tactical innovation of the bomber stream by the RAF to overwhelm the German aerial defenses of the Kammhuber Line during World War II would have increased the RAF's concentration in time over the target, but after the lessons learned during the Blitz, the tactic of dropping a high concentration of bombs over the target in the shortest time possible became standard in the RAF because it was known to be more effective than spreading the raid over a longer time period.

For example, during the Coventry Blitz on the night of 14/15 November 1940, 515 Luftwaffe bombers, many flying more than one sortie against Coventry, delivered their bombs over a period of time lasting more than 10 hours. In contrast, the much more devastating raid on Dresden on the night of 13/14 of February 1945 by two waves of the RAF Bomber Command's main force, involved the bomb released at 22:14, with all but one of the 254 Lancaster bombers releasing their bombs within two minutes, and the last one released at 22:22.

The second wave of 529 Lancasters dropped all of their bombs between 01:21 and 01:45. This means that in the first raid, on average, one Lancaster dropped a full load of bombs every half a second and in the second larger raid that involved more than one RAF bomber Group, one every three seconds.

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) officially only bombed precision targets over Europe, but for example, when 316 B-17 Flying Fortresses bombed Dresden in a follow-up raid at around noon on 14 February 1945, because of clouds the later waves bombed using H2X radar for targeting.

The mix of bombs to be used on the Dresden raid was about 40% incendiaries, much closer to the RAF city-busting mix than the bomb-load usually used by the Americans in precision bombardments. This was quite a common mix when the USAAF anticipated cloudy conditions over the target.

In its attacks on Japan, the USAAF abandoned its precision bombing method that was used in Europe and adopted a policy of saturation bombing, using incendiaries to burn Japanese cities. These tactics were used to devastating effect with many urban areas burned out.

The first incendiary raid by B-29 Superfortress bombers was against Kobe on 4 February 1945, with 69 B-29s arriving over the city at an altitude of 24,500 to 27,000 ft (7,500 to 8,200 m), dropping 159 tons of incendiaries and 14 tons of fragmentation bombs to destroy about 57.4 acres (23.2 ha).

The next mission was another high altitude daylight incendiary raid against Tokyo on 25 February when 172 B-29s destroyed around 643 acres (260 ha) of the snow-covered city, dropping 453.7 tons of mostly incendiaries with some fragmentation bombs.

Changing to low-altitude night tactics to concentrate the fire damage while minimizing the effectiveness of fighter and artillery defenses, the Operation Meetinghouse raid carried out by 279 B-29s raided Tokyo again on the night of 9/10 March, dropped 1,665 tons of incendiaries from altitudes of 5,000 to 9,000 ft (1,500 to 2,700 m), mostly using the 500-pound (230 kg) E-46 cluster bomb which released 38 M-69 oil-based incendiary bombs at an altitude of 2,500 ft (760 m).

A lesser number of M-47 incendiaries was dropped: the M-47 was a 100-pound (45 kg) jelled-gasoline and white phosphorus bomb which ignited upon impact. In the first two hours of the raid, 226 of the attacking aircraft or 81% unloaded their bombs to overwhelm the city's fire defenses.

The first to arrive dropped bombs in a large X pattern centered in Tokyo's working class district near the docks; later aircraft simply aimed near this flaming X. Approximately 15.8 square miles (4,090 ha) of the city were destroyed and 100,000 people are estimated to have died in the resulting conflagration, more than the immediate deaths of either the atomic bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. After this raid, the USAAF continued with low-altitude incendiary raids against Japan's cities, destroying an average of 40% of the built-up area of 64 of the largest cities.

Paradigm shift. November 7, 2004. Journalists embedded with U.S. military units in Iraq, severely limited in what they could report, filed the following account on the U.S. offensive on Fallujah.

On November 8, 2004, a force of around 2,000 U.S. and 600 Iraqi troops began a concentrated assault on Fallujah with air strikes, artillery, armor, and infantry. They seized the rail yards North of the city, and pushed into the city simultaneously from the North and West taking control of the volatile Jolan and Askari districts.

Rebel resistance was as strong as expected, rebels fought very hard as they fell back. By nightfall on November 9, 2004, the U.S. troops had almost reached the heart of the city. U.S. military officials stated that 1,000 to 6,000 insurgents were believed to be in the city, they appear to be organized, and fought in small groups, of three to 25.

Many insurgents were believed to have slipped away amid widespread reports that the U.S. offensive was coming. During the assault, Marines and Iraqi soldiers endured sniper fire and destroyed booby traps, much more than anticipated. Ten U.S. troops were killed in the fighting and 22 wounded in the first two days of fighting. Insurgent casualty numbers were estimated at 85 to 90 killed or wounded. Several more days of fighting were anticipated as U.S. and Iraqi troops conducted house-to-house searches for weapons, booby traps, and insurgents.

On 9 November, CNN Correspondent Karl Penhaul reported the use of cluster bombs in the offensive: "The sky over Falluja seems to explode as U.S. Marines launch their much-trumpeted ground assault. War planes drop cluster bombs on insurgent positions and artillery batteries fire smoke rounds to conceal a Marine advance."

November 10, 2004 reports by the Washington Post suggest that U.S. armed forces used white phosphorus grenades and/or artillery shells, creating walls of fire in the city. Doctors working inside Fallujah report seeing melted corpses of suspected insurgents. The use of white phosphorus ammunition was confirmed from various independent sources, including U.S. troops who had suffered WP burns due to friendly fire.

On November 16, 2005 The Independent reported that Pentagon spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Barry Venable "disclosed that (white phosphorus) had been used to dislodge enemy fighters from entrenched positions in the city"..."We use them primarily as obscurants, for smokescreens or target marking in some cases.

However, it is an incendiary weapon and may be used against enemy combatants." But a day before, Robert Tuttle, the U.S. ambassador to London, denied that white phosphorus was deployed as a weapon: "US forces do not use napalm or white phosphorus as weapons."

On November 13, 2004 a Red Crescent convoy containing humanitarian aid was delayed from entering Fallujah by the U.S. army.

On November 13, 2004, a U.S. Marine with 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines was videotaped killing a wounded and unarmed prisoner in a mosque. The incident, which came under investigation, created controversy throughout the world. The man was shot at close range after he and several other badly wounded Iraqi prisoners had previously been left behind overnight in the mosque by the U.S. Marines. The Marine shooting the man had been mildly injured by insurgents in the same mosque the day before. In May 2005, it was announced that the Marine would not face a court-martial. In a statement, Maj. Gen. Richard F. Natonski, commanding general of the I Marine Expeditionary Force, said that a review of the evidence had shown that the shooting was "consistent with the established rules of engagement and the law of armed conflict."

On November 16, 2004, a Red Cross official told Inter Press Service that "at least 800 civilians" had been killed in Fallujah and indicated that "they had received several reports from refugees that the military had dropped cluster bombs in Fallujah, and used a phosphorus weapon that caused severe burns."

As of November 18, 2004, the U.S. military reported 1200 insurgents killed and 1000 captured. U.S. casualties were 51 killed and 425 wounded, and the Iraqi forces lost 8 killed and 43 wounded.

On December 2, 2004, the U.S. death toll in Fallujah operation reached 71 killed.

Some of the tactics said to be used by the insurgents included playing dead and attacking, surrendering and attacking, and rigging dead or wounded with bombs. In the November 13th incident mentioned above, the U.S. Marine alleged the insurgent was playing dead.

Of the 100 mosques in the city, about 60 were used as fighting positions by the insurgents.[citation needed] The U.S. and Iraqi military swept through all mosques used as fighting positions, destroying them, leading to great resentment from local residents.

In 2005, the U.S. military admitted that it used white phosphorus as an anti-personnel weapon in Fallujah.

On 17 May 2011, AFP reported that 21 bodies, in black body-bags marked with letters and numbers in Roman script had been recovered from a mass grave in al-Maadhidi cemetery in the centre of the city. Fallujah police chief Brigadier General Mahmud al-Essawi said that they had been blindfolded, their legs had been tied and they had suffered gunshot wounds. The Mayor, Adnan Husseini said that the manner of their killing, as well as the body bags, indicated that US forces had been responsible. Both al-Essawi and Husseini agreed that the dead had been killed in 2004. The US Military declined to comment.