Lives in Translation

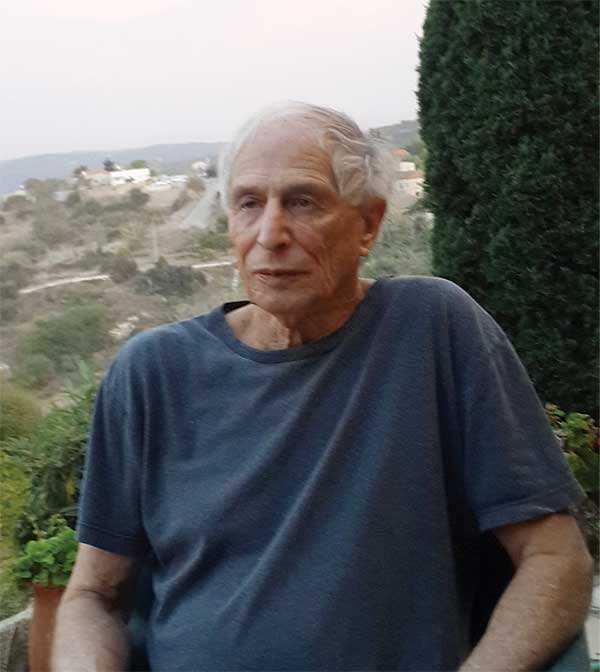

The prolific, polymathic Israeli writer Hillel Halkin was born in New York in 1939, the son of Hebraists. He made his auspicious debut in 1962 as the translator of Moshe Shamir and Yehuda Amichai in Israeli Stories, a landmark collection published by Schocken Books. Its editor, Joel Blocker, wrote this in his preface:

Special care has been taken to avoid the archaisms and crudities in language which in the past have often vitiated Hebrew literature in English. Freed of its artificial quaintness, Hebrew prose can be enjoyed and evaluated like any other modern literature.

Over the years, Halkin has translated this credo into a remarkable career.

The heyday of artificial quaintness was the 19th century, when Hebrew writers in Eastern Europe struggled to carve a new literature—poems and essays, stories and novels—out of lives spoken in Yiddish and a language learned in yeshivas and shuls. These figurative ancestors are the heroes of Halkin’s latest book, The Lady of Hebrew and Her Lovers of Zion. Its poetic title is a far cry from his first, Letters to an American Jewish Friend: A Zionist’s Polemic. With pilpulistic flair, he shadowboxed with a composite friend—a peer, an educated and committed Jew—reaching an inexorable conclusion: American Judaism was doomed, and for serious Jews the only logical choice was to make aliyah, as he had done in 1970. He made it clear that this was not a heroic sacrifice, nor a trial run, but permanent.

Letters, echoing Moses Hess’s epistolary classic Rome and Jerusalem, became part of the Zionist canon, winning a National Jewish Book Award. It sold poorly, but people passed it hand to hand, and it deeply affected many readers, including this reviewer. “A land and a language! They are the ground beneath a people’s feet and the air it breathes in and out,” he wrote from Zikhron Yaakov, where he lives to this day. “As hard as it is to be what you are, it would be even harder to be what you are not.” Upon rereading the book, one is impressed by its confidence, its sheer chutzpah. Seven years in Israel, and already an Israeli.

The Lady of Hebrew may be read as a mellower metamorphosis or gilgul of his Zionist riff, half a century after his famous aliyah. The book consists of 12 long, opinionated essays, of which 10 appeared in Mosaic magazine between 2015 and 2018:

They have two purposes. One is to introduce English readers having little or no familiarity with them to a number of major Hebrew authors of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries whose work forms an important part of the literary response to the modern Jewish experience. The other is to explore the reciprocal relationship in this period between Hebrew literature, the evolution of the modern Hebrew language, and the emergence of Zionism as a historic force in Jewish life.

Halkin succeeds on both counts.

The essays are meticulously constructed and elegantly written. The Lady of Hebrew also serves as a showcase for his superior talents as a translator. “All the translations in this book are my own,” he explains. “Considerable space has been devoted to them. . . . I wished to give the reader a palpable sense of the prose and poetry of writers who have been mostly translated into English poorly or not at all.” Refashioned by Halkin, their words foreshadow the major themes of his Letters to an American Jewish Friend. He argues:

Without Hebrew literature, Zionism would never have been a significant force in East-European Jewish life. Without Zionism, Hebrew literature had no future readership to look forward to. Their relationship was symbiotic.

His Lovers of Zion stroll through his pages, hand in hand with the Lady of Hebrew. Some Lovers spurn Zionism, but all of them enable it. Some settle in Palestine: Brenner, A. D. Gordon, Bialik, Ahad Ha’am, the poet Rahel, the incomparable Agnon. The journey was never easy. In Letters, Halkin described the everyday hardships of Israeli life, the frequent reserve duty, the high taxes. Over the years, he published further tantalizing bits of autobiography. Halkin avoids the limelight here, unobtrusively braiding his characters’ lives and their Hebrew writings. But their stories are his too. In the end, he is one of them.

They are also the kind of writers he likes best: dead ones. In a Prooftexts essay in 1983 called “On Translating the Living and the Dead,” he declared this:

All in all, I think, I would rather translate the dead. They do not complain. They do not argue. They do not fret about their reputations. They do not call you on the telephone at eleven o’clock at night to ask why they have not received the chapter you promised them a week ago. They do not think they know English better than you do. Most of them never knew it at all. . . . When translating the dead one enjoys much more freedom than one does with the living—and with it, as with all freedom, comes more responsibility. . . . When translating the dead, I must say, I have a sense of mission that I do not feel with the living. They have so little going for them. . . . They cannot be interviewed, appear on talk shows, or give public readings from their latest work. All they have, if they are lucky, is a translator. And they cannot even defend themselves against him.

The Lady of Hebrew is a splendid companion for Anglophone Hebraists, fellow translators not least. Housebound by the pandemic, I rummaged through my shelves and rediscovered inherited copies of Brenner, Berdichevsky, and Bialik, Mendele Mokher Seforim, even Kvurat Hamor (A Donkey’s Burial) by Peretz Smolenskin. I consulted the originals and marveled at Halkin’s ingenuity. He is especially attuned to the changing nature of Hebrew, charting its evolution from Abraham Mapu’s “neoclassical pastiche of post-biblical and biblical Hebrew” to Agnon’s eclectic layering of rabbinic Hebrew and modern speech. In his novel of 1853, Ahavat Tzion (The Love of Zion), a corny romance in the days of King Hezekiah, the Lithuanian-born Mapu imagined his young couple: “Like two fluttering doves, their eyes, too shy to meet, skimmed the gladsome water, each glimpsing the other’s fair form in its faithful mirror.” Clicking on Mapu at benyehuda.org yields the original of the archaic “gladsome”: asher hisbi’am ne’imot, hifalutin Hebrew for “made them glad.”

Mapu inspired both halves of Halkin’s title: “The ‘Lady of Hebrew’ is how I have translated Mapu’s ‘ha-Ivriyya,’ literally ‘the Hebrewess,’ a favorite term of his.” This personification “reached rhapsodic heights” in a letter to the literary scholar Shneur Sachs, who had urged him to write a Hebrew novel:

It was you, my friend and mentor, it was you who gave me the courage and inspired me to seal my pact with my Lady of Hebrew. I remember the day on which I removed the veil from her face, lo, there was the daughter of Zion in all her loveliness of yore! Bewitchment upon her lips, she said: “Gaze upon me, thou champion of Zion, and tell me why the sons I raised have disdained me.”

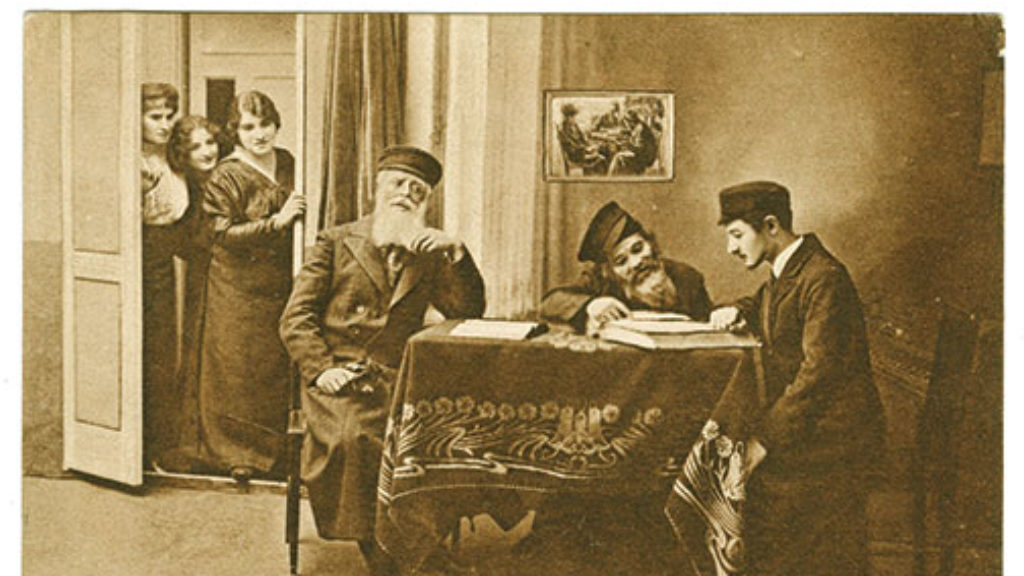

Halkin challenges the widespread view that Mapu’s Ahavat Tzion was the first Hebrew novel. That laurel belongs to the forgotten Joseph Perl (1773–1839), whose credits include an epic Hebrew translation (from a German version) of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. Perl, a Galitzianer from Tarnopol, was an Orthodox Jew yet a strong proponent of the Haskalah, which begat Reform and secular Judaism. Halkin furnishes historical background about the battles between Hasidim and their Orthodox opponents, the mitnagdim. Hasidism posed a threat to rabbinic authority and conjured the frightening specter of antinomian Sabbateanism. (Nowhere in the book does Halkin mention Scholem, whose seminal essay “Redemption Through Sin” he translated in 1971. Nor does The Lady of Hebrew have a bibliography to steer the reader to other intriguing works.)

Perl the Orthodox maskil wrote an exposé in German titled Über das Wesen der Sekte Chassidim aus ihren eigenen Schriften gezogen (On the Essence of the Hasidic Sect, Drawn from Their Own Writings), but it was censored by Austrian authorities, who feared disruptive Hasidic backlash. “Undaunted,” writes Halkin, “Perl proceeded to do the next best thing by turning his disappointment into a novel.” This was Megaleh Temirin (The Revealer of Secrets), published in Vienna in 1819. It masqueraded as an epistolary novel written from a Hasidic point of view but was, in fact, a scathing satire of Hasidism, mocking the faulty Hasidic Hebrew of such hagiographic works as Shivchei HaBesht (Praises of the Ba’al Shem Tov). Halkin dutifully summarizes Perl’s convoluted plot, so “wild and woolly” that “even the most highly concentrated reader can at times lose the thread of it.” Still, it’s a feast for the translator:

Yesternight I lingered at our Holy Rabbis after the Evening Prayer & heard him say a few words. They were sweeter than honey & I was much pleased by his being in fine fetal & cozy as always with God. . . . I could have listened to his Holy Words for days without eating or drinking but he wanted to have a Smoak & go the Privee & so I fetched him his Pipe. . . . And when I saw it was not his pleasure to be walked to the Privee I went home in a merrie mood thanking God for my good fortune at being in our Holy Rabbis Inner Circle & hearing such Amazing Things.

Halkin applauds the “vibrancy” of Hasidic Hebrew, which “had a spontaneity and naturalness that Maskilic Hebrew lacked,” but rejects Perl’s portrait of Hasidism as “simply one huge swindle” rather than the “revolutionary movement that galvanized the Jewish masses of Eastern Europe with its faith, dynamism, and valorization of the ordinary Jew.” For Halkin, Zionism strove to “tap the religious energy of Hasidism for secular purposes”:

For success to be possible, Zionism had to adopt not only the Haskalah’s critical habits of thought but many of the features of Hasidism: its enthusiasm, its rebellion against established authority, its missionizing zeal, its anti-elitist character, its messianic impulses, its faith in miracles.

Halkin wrote this to his American Jewish friend:

It’s an old and tiresome story, this business of the loss of religious faith. It is indeed the story of our modern Jewish times. You will find one version or another of it, for example, in practically every serious work of late nineteenth- or early twentieth-century Hebrew literature, with which I do not propose to vie here.

But vie he did, in a vivid passage:

You may know that I grew up in a more or less Orthodox home and received an Orthodox education, but I probably never told you that for a year or two of my life, between the ages of twelve and fourteen, I went through an intensely religious period such as sometimes occurs in conjunction with puberty. My own parents were so taken aback by the fanaticism of it that they were at a loss to decide whether they had a tzaddik or a nudnik on their hands. It wasn’t only that I scrupulously prayed three times a day, or refused to take four steps without a hat on my head, or wore a fringed arba kanfoth under my clothing that in hot weather especially tormented me like a hairshirt, or studied a nightly page of Talmud even on soft summer evenings when the street was calling outside. It was that I did all this in a swoon of devotion worthy of a priest in the Temple. . . . It didn’t last.

In “Either/Or,” an autobiographical piece for Commentary in 2006, Halkin likened his religious phase to “Ha-matmid,” the famous poem by Bialik that boys like him (and me) read in Modern Orthodox day school:

“At a time when the stars are aglitter / And the grasses whisper and the wind tells its tales, / A plangent voice may reach your ears, / And your eyes may spy a distant light / In a window, and through it / A shadow like a ghost’s, / Swaying, moving, moving, rocking back and forth, / Its soft croon coming to you / Across pathways of silence: / It is a Talmud student, / Up late in his prison cell.” We had studied this Hebrew poem by Haim Nahman Bialik in school. Now I swayed, moved, in its lines.

Halkin left the Ramaz School for Bronx High School of Science. He spent the summer before his senior year in Tennessee, as a volunteer at the Highlander Folk School, a liberal educational center. “That summer marked the end of my religious observance,” he confessed in “Either/Or.” “In early July I was still putting on my tefillin, which I had brought to Tennessee in their velvet pouch. By the end of August I was eating pork.”

For his part, Bialik dropped out of the prestigious Volozhin yeshiva, lost his faith, and settled in Odessa, where, in 1903, he was dispatched by Jewish leaders to report on the Kishinev pogrom. His report was a poem, “The City of Slaughter,” a chilling indictment of Jewish passivity composed in perfect rhyme. In 1924, he moved at age 51 to Tel Aviv, where he dried up as a poet and flourished as a culture-hero of the new Hebrew city. He died 10 years later in Vienna at age 61, following prostate surgery. In his Lady of Hebrew translation of the devastating Kishinev poem, Halkin gives us a taste of the rhymed structure: “The boards / Of fences, and the stone of houses, and the plaster, and the wood, / And the clotted brains of victims and their dried blood.” Such words, writes Halkin, “hit their reader with a gale force.”

Before Letters, Halkin had translated a stormy classic of religious rebellion, the subversive novella Le-an? (Whither?) by Mordecai Ze’ev Feierberg. It was published in 1899 by Ahad Ha’am in his monthly journal Ha-shiloach. I read it long ago in Hebrew, assigned by an Israeli teacher at my Modern Orthodox high school. (Is it still taught in such places?) Feierberg’s fierce iconoclasm and Zionism made a lasting impression on me, akin to that of Portnoy’s Complaint in college and, later on, Halkin’s Letters, which I first read in Hollywood to help decide if I should move to Israel.

Feierberg was the son of a sternly religious Lubavitcher Hasid, a shochet in Novograd-Volinsk. In Le-an?, Nachman, 20-year-old son of rigid Rabbi Moshe, is tormented by the Evil Urge. Terrified by his father’s warnings of divine punishment, his sensitive mind stuffed with Maimonides, Nachmanides, and Gersonides, not to mention Spinoza and Darwin, he is driven by his demons to commit an act of whole-hog heresy: blowing out a candle in the synagogue on Yom Kippur. Known henceforth as “Crazy Nachman,” he emerges from months of depression with an epiphany: the Land of Israel. Listen to his impassioned speech at a local Zionist meeting, in the words of Halkin’s Whither? and Other Stories:

You, my brothers . . . are gathered here tonight to seek a cure for our people’s illness and to help restore it to its ancient homeland. . . . Europe is ailing now—everyone feels how our civilization is coming apart and how its pillars of faith are already eaten through. . . . And if the Jewish people has a destiny to fulfill, let it forge that destiny and that truth for itself and take it with them to the East. . . . To the East! To the East!

This is classical Zionism in a nutshell. Feierberg died of tuberculosis in his twenties. He plays only a supporting role in The Lady of Hebrew, his full story having been well told in Halkin’s introduction to Whither?, as well as “Banished from Their Father’s Table”: Loss of Faith and Hebrew Autobiography by his friend Alan Mintz, to whose memory the new book is dedicated. Feierberg endures in Tel Aviv, two blocks west of Rothschild. My kids live nearby and know the street but haven’t the foggiest for whom it’s named. In his essay on dead authors, Halkin described translating Feierberg as a “labor of love” that sold maybe a thousand copies, “yet if it enabled even that many readers to get to know his work it was worth it.”

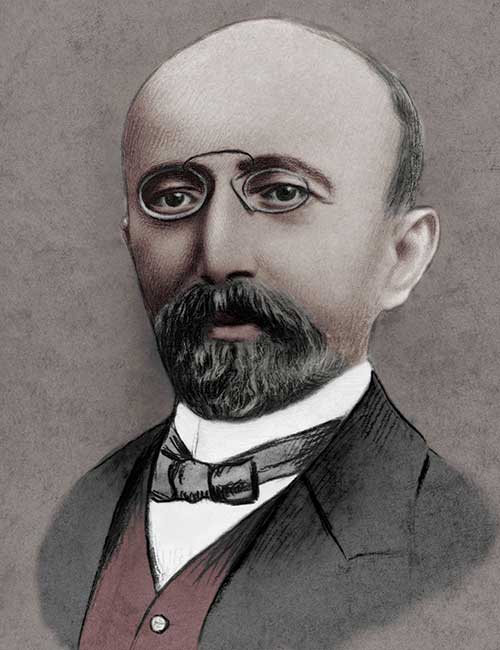

Halkin, the secular matmid, continues to valorize Hebrew renegades. Peretz Smolenskin, born circa 1840 in White Russia, was educated at the Shklov yeshiva and expelled for secretly reading Haskalah literature. “Most yeshivas had their clandestine cells of budding Maskilim,” notes Halkin—who else knew enough Hebrew? Kvurat Hamor and Smolenskin’s other novels of Jewish life in the Russian Pale of Settlement stood out for their Dickensian characters—“rustic villagers, wealthy contractors, klezmer musicians,” “cabaret singers, apostates,” “philanthropists, authors, Hebrew poets.” The “grand cause” of Smolenskin’s life, in Halkin’s reading, was Jewish peoplehood that transcended “Mosaic faith,” and he “needed fiction to command an imaginative view of it.” He moved to Vienna, where he founded an important Hebrew journal called Ha-shachar, “The Dawn.” It was in Ha-shachar in 1879 that Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a 21-year-old medical student, called for a national territory in Palestine where Jews would speak Hebrew as their native tongue, “the first in the world of Hebrew letters to do so.” Smolenskin was sympathetic but skeptical.

The Haskalah poet Yehudah Leib Gordon, born in Vilna in 1830 to a religious family, is best known for his one-liner that one should be a Jew in one’s “tent” and a human being when one leaves it. In St. Petersburg, he edited the Hebrew newspaper Ha-melitz and endorsed Jewish emigration to America, not Ottoman Palestine. Gordon was a virtuoso of Jewish self-criticism, but only when writing in Hebrew. In Russian, he defended the Jews at every turn. “Hebrew,” remarks Halkin, “provided Jews with a protected private space of their own. Their secrets were safe in it. . . . Not even Yiddish, which not a few Russians had some knowledge of, was as hermetic.”

Early on, Gordon wrote animal fables in verse, designed as a textbook for teaching Hebrew. In the event, Mishlei Yehuda was adopted only by a Karaite school in Crimea, but it’s catnip for Halkin: “A donkey staggered down a road / Beneath some heavy bags of grain / When a noble steed came prancing by / Burdened only by its bit and rein.” (Moral: Rich Jews should help poor ones.) Gordon’s poem “Kotso shel yud” (“The Tip of a Yud”), published in 1875 in Ha-shachar, bemoaned the triumph of narrow Orthodoxy over common sense. He wrote dejectedly in a letter to a lifelong friend: “Can’t you see where we are heading and what will happen to us in the end of days? The Sadducees will study Greek and the Pharisees will expound the laws of the bathroom.” Plainly put, the Haskalah would bring assimilation, and the rabbis would split halakhic hairs.

In “Zedekiah in the Dungeon,” Gordon blamed the zealous prophet Jeremiah for the destruction of the First Temple:

I see how on that distant day / The son of Hilkiah will have his way. / His dispensation will prevail; All governance will founder and then fail; / Our people, erudite in chapter and in verse, / Will go from woe to woe and bad to worse.

Writes Halkin: “In the entire history of Hebrew literature, no critique of Judaism had ever been more sweeping or more damning.” If the Jews couldn’t maintain self-rule in antiquity, Gordon feared, the prospects for Zionism were bleak. In a Jewish country, he warned in Ha-melitz, “every fanatic and wide-eyed zealot will be able to wreak havoc by blowing the ram’s horns of excommunication and furiously turning on whoever’s ideas and behavior do not accord with his own.” In literary circles, Yehudah Leib Gordon was hailed as the “Jewish national poet,” acronymically crowned as “Yalag.”

Yosef Hayyim Brenner, raised in a Ukrainian shtetl, wrote seven short autobiographical novels by the time he was 30. The last of these, Mikan u’mikan (From All Sides), published in 1911, was the first major work of Hebrew fiction written in Palestine. “Like all of Brenner’s fiction,” writes Halkin, it is “dark and anguished.” He was influenced by Dostoevsky and feigned indifference to art. In his Prooftexts essay, Halkin recalled wrestling with Brenner’s magnum opus, Breakdown and Bereavement, “cursing him all the while for his carelessness, for his sloppiness, for his contempt for his own talent, for his infuriating refusal to write as well as he could have. . . . I was wasting my time. He needed an editor fifty years ago, not a translator now.” The current essay dwells on Mikan u’mikan and richly quotes its wordy protagonists, based on Brenner and his friend A. D. Gordon, the quasi-Hasidic Tolstoyan who made aliyah in middle age and personified the Jewish return to the soil. Gordon in the novel is named Aryeh Lapidot, and pessimistic Brenner is named Oved Etsot, which Halkin translates as “Out of Advice.” As they argue the world—Zionism, Judaism, the Land of Israel—sparks fly. Says Oved Etsot:

Alive. Yes, to live. And a man must live—well, no, not must, but it’s good if he does—in one place. . . . It may be—it may very well be—that it’s impossible to live in this place, but one must live in it anyway. One must die in it. There’s nowhere else.

In 1920, after Joseph Trumpeldor was killed at Tel Hai, Brenner wrote that by all logic, the village should have been evacuated before the hostile Arabs could arrive. He wrote:

But the heart, the selfless heart, believed in miracles; it believed the normal laws would be suspended; that devotion was everything; that love for a piece of earth could move mountains. Besides, if we left every place in which there was danger, there would be no place we would not have to leave, no position we would not have to retreat from—but to where? And what now? Danger is everywhere.

You move here; you accept that. Brenner was killed in an Arab-Jewish clash the following year in a farmhouse near Jaffa at age 39.

One cannot fail to be reminded of Judah Halevi, slain by an Arab on his arrival in Jerusalem, or so the story goes. In his masterful 2010 biography of Halevi (lauded in these pages by Robert Alter), Halkin took time out to meditate on his disoriented life back in the 1960s:

And spent a year in Alabama. And followed Laura to California, where she started law school. And broke up with her and moved with our two Irish setters to a house in a redwood forest. And left the setters and took a Greyhound bus back to New York. And set out for New England in a borrowed car with $1,500 in cash and drove and drove until the price of land fell enough to buy 150 acres of woods with a brook in the middle of Maine. I was full of Thoreau and The Whole Earth Catalog, and I was going to build a log cabin and live in it.

Many are the winding roads that lead to aliyah. The towering medieval Hebrew poet sang of Zion and wrote his Jewish polemic, The Kuzari, in Spain, unable or unwilling, like Halkin’s American friend, to get serious about moving to Israel. Only in old age—between 65 and 70, reckons Halkin—did the poet set sail for Palestine: “Franz Rosenzweig, himself a translator of Halevi, put it well when he said: ‘If ever a life went into the ripening of a single deed, this was the one.’” The budding Hebraist from the Maine woods has ripened in old age. Zikhron Yaakov, the 19th-century settlement south of Haifa, where young halutzim worked the fields and danced the hora under the baton of Baron Rothschild, is the perfect setting for the compleat secular Zionist author, composing an essay in English called “Ahad Ha’am Writes a Book Review.”

Theodor Herzl, the dazzling impresario of the Jewish

state, published his utopian Zionist novel Altneuland in 1902. His

biography is legend: assimilated Viennese journalist and mediocre playwright,

galvanized by antisemitism, creates the Jewish state at the Zionist Congress in

1897 and dies seven years later at age 44. Herzl didn’t know Hebrew, couldn’t

imagine buying a railroad ticket in Hebrew. Ahad Ha’am (“One of the People”)

was the pen name of Asher Ginsberg, the finest Hebrew essayist of his day, born

to Hasidic parents in Ukraine. He ditched Orthodoxy but reveled in Jewish

culture and resented Herzl, whom he considered a charlatan and an upstart. Ahad

Ha’am had been the leading spokesman for Zionism, advocating the patient

creation of a spiritual center in Eretz Yisrael as an antidote to diaspora

assimilation. He attended the Herzl-

dominated 1897 Zionist Congress in Basel, where he felt, as he put it, “like a

mourner at a wedding.”

Ahad Ha’am loathed Altneuland. “Achen nodah hadavar!” he began, or in Halkin’s translation, “The cat is out of the bag!” He denounced Herzl for concocting a Jewish society empty of Jewish content:

Imitating others without the slightest originality, going to all lengths to avoid anything smacking of national chauvinism, even if this means obliterating a people’s nationality, language, literature, and spiritual propensities; making oneself small to show how great, even revoltingly so, is one’s tolerance. . . . A Jewish renaissance that would truly be Jewish cannot be created overnight by stock companies and cooperatives. A historic ideal demands historic development, and historic development takes time.

Herzl, in the face of rising antisemitism, was in a hurry to create a Jewish refuge, ideally in Palestine, though Argentina or East Africa might do. Altneuland was an effort to popularize the plan he had laid out in his tract Der Judenstadt. In his ideal Jewish Palestine, everyone speaks German, even the Arabs, who are grateful for the modernizing Jewish presence. In the early 1890s, Ahad Ha’am had made two trips to Palestine and written “Ha-emet me-Eretz Yisrael,” a pair of essays in Ha-shiloach telling the hard truth: The land was not ripe for emigration, and Arab resentment should not be underestimated. Ahad Ha’am finally made aliyah from London to Tel Aviv in 1922 and died there five years later at age 70.

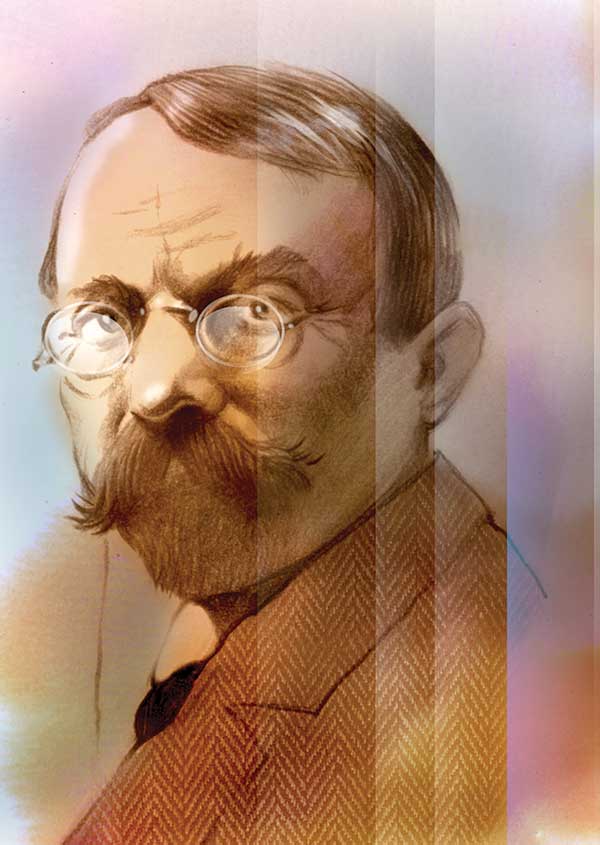

As supporters of Herzl versus Ahad Ha’am squared off in the Hebrew press, Micha Yosef Berdichevsky took aim at both camps. Born in 1865 into a rabbinic family in Ukraine, he dropped out of the Volozhin yeshiva, earned a PhD in German philosophy in Bern, and settled in Wroclaw, where his wife had a dental clinic. He wrote bold, provocative fiction, including transparently autobiographical stories about young Jews losing their religion and a wild depiction of Jewish savagery in “The Red Cow,” in which kosher butchers lick the blood of the slaughtered animal. (Here I must pick a halakhic nit: Berdichevsky specifies that the blood was bli melicha, without salting. Halkin omits the important detail; a stricter translation by Rabbi William Cutter, aptly titled “The Red Heifer,” retains it.) Most significantly, Berdichevsky penned trenchant essays in a Nietzschean vein, urging the transvaluation of Jewish values:

God was buried beneath the Torah, the world beneath a book. Man stifled his senses and became a guardian of parchment. . . . An ancient tribe went looking for a country and found a tome of commandments. . . . Then came the one God from the desert to give us an eternal scripture into whose occult sinkhole we sank and have never stopped sinking. . . . Not for nothing do we fear that we have left familiar territory and are faced with the collision of “to be” with “not to be.” We will be either the last Jews or the first Hebrews.

“Not even [Yehuda Leib] Gordon had dared launch such an all-out Hebrew assault on Judaism,” writes Halkin. Young Zionists, Ben-Gurion among them, were energized by Berdichevsky’s message of radical reinvention. “It would be hard to think of another Hebrew writer of the age for whom Zionism was a more obvious cause to embrace. . . . As an idea, he was for it, as a movement, he had little faith in it.” Berdichevsky thought Herzl was acting like a philanthropist, “under the delusion that grand assemblies and gestures could accomplish for a people what it was unprepared to do for itself.” At the same time, he saw Ahad Ha’am’s spiritual center as “no less of a fantasy than Herzl’s Jewish state.”

Berdichevsky never so much as visited Palestine, comparing its inhabitants to the ancient Israelites who danced around the golden calf. “Did he mock secular Tel Aviv,” wonders Halkin, “because he had come to perceive the shallowness of the post-religious Jew as much as he did the narrow-mindedness of the religious Jew? He could not stop wrestling with tradition.” As Brenner once put it, Berdichevsky felt that “he and Jewish people were one.” By which he meant, says Halkin, “that he contained in himself every contradiction and conflict of Jewish history, in which there was no period, prominent figure, or tendency that he did not feel to be part of himself.”

Halkin, who has also translated Yiddish literature, empathizes with the great Yiddish writer Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh, better known as Mendele Mokher Seforim, a man torn between languages. Mendele reverted to Hebrew in 1887, with a tale called “B’seter ra’am” (“In the Hidden Place of Thunder”). He had written in Hebrew in the 1860s, in the stilted prose of the Haskalah. Now, writes Halkin, “without uprooting Hebrew from its classical matrix, he found ways of transferring to it the freedom he had gained from Yiddish,” retaining the folksy intonations of Jewish speech. “B’seter ra’am” takes place in the fictitious town of Kislon, translatable as “Foolsville.” Here are the words of Mendele the Bookseller, the story’s narrator:

If you, my friends, were not born there yourselves, your parents most certainly were, and if Kislonite blood does not flow in each lode of your veins, it is sure to be found in some lobe of your brains. Yea, I was young and now I am old, says the Psalmist, and never have I met a Jew who did not, in deed or demeanor, be his business with man or with God, remind me of Kislon.

Thirty years ago, Halkin published a fascinating article titled “Adventures in Translating Mendele.” Here he provided the first Hebrew paragraphs of “B’seter ra’am” and nine drafts of his English version, listing their problems and solutions. “Each lode of your veins” is Halkin’s choice for kol rema”ch evarchem u’she”sa gidchem, a numerological idiom that rewards Hebrew readers and confounds translators. Halkin’s first draft had “every last capillary of your bodies” and “some crevice of your brains”; by the eighth it was “node of your brains”; and now it has morphed into “lobe,” which goes nicely with “lode.” The article illustrated the obsessive attention to detail and continual second-guessing of the true professional. It also struck me as a metaphor for Mendele’s own “ambivalations” (if not a word, it should be). In a later story called “Be-yeshiva shel mata” (“Those Assembled Below”)—the title plays on the Kol Nidrei prayer—Mendele agrees with a variety of views on Zionism. Halkin says:

And so it goes. Mendele agrees with every opinion he hears, even if it contradicts what he has agreed with a minute ago. The question of Zionism, it appears, is so complicated that everything said about it is true. . . . Yes, it is illogical to be a Zionist, a non-Zionist, and an anti-Zionist at one and the same time. But each of these positions has its own logic—and logic, in any case, never determined the course of history, which is beyond our control and predictive ability. . . . It is not foolish in such a situation to hedge one’s bets.

Halkin devotes his final essays to two giants of the Second Aliyah, Rahel Bluvshteyn, known by her first name only, and S. Y. (Shai) Agnon. Born in Russia in 1890, Rahel first visited Palestine in 1909, studied agriculture in France, and later went to live at Kibbutz Degania, of which A. D. Gordon was a member. She took care of little Moshe Dayan and the other children until she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and left the kibbutz. She died in 1931 and was buried on the shore of her beloved Kinneret, the Sea of Galilee. Rahel never married but reputedly had various suitors and lovers, including Zionist luminaries Berl Katznelson and Zalman Rubashov, who much later became President Shazar.

Halkin compares Rahel to Emily Dickinson—short lines, similar phrasing, and “wryness of tone”—but hears in Rahel’s poetry “a quiet anger at her fate not found in Dickinson.” “With the possible exception of Bialik,” he writes, “no Hebrew poet from the pre-State of Israel period continues to have so large a readership.” Her poems have been set to music, and her face now adorns the 20-shekel bill. She famously wrote“V’ulai”: “And perhaps it never happened that way? / Perhaps / I never set out for work on the garden path / In the first light of day?” The late American-born Israeli poet Robert Friend rendered it quite differently: “Was it only a dream? Was it I? / Was it I who long ago / rose with the dawn to fill the fields / by the sweat of my brow?” (Admirers of this consummate Lady of Hebrew would do well to acquire Friend’s dual-language edition, Flowers of Perhaps, to compare and contrast with Halkin’s Rahel.)

“Agnon’s Tale of Two Cities” is an intricate reading of the sprawling Tmol shilshom, the canonical masterpiece of the Second Aliyah. Born in Buczacz (then Poland, now Ukraine), Agnon made aliyah to Jaffa at age 20 in 1908. The novel’s protagonist, Yitzhak Kummer, oscillates between secular Jaffa and ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem. Halkin copiously quotes and closely reads gorgeous passages that typify Agnon’s novel. To demonstrate the difficulty of producing an English version, he brings a passage from Only Yesterday, Barbara Harshav’s translation for Princeton University Press, which he tersely describes as “more literal than mine.” He explains:

English, having never passed through a rabbinic period, has no equivalents of rabbinic language. It is possible to translate Agnon well by transmitting other elements of his style—its careful symmetries, its back-and-forth, Talmudic rhythms, its tongue-in-cheek slyness—but any attempt to imitate it more closely is doomed to fail.

The book is narrated in the plural “we” by a nameless fellow immigrant. Halkin calls Agnon the “wiliest of all Hebrew writers.” From the first sentence of Tmol shilshom, he puts the reader off balance. Yitzhak Kummer leaves his hometown “for the liberation of our people, setting out for the Land of Israel to rebuild it from its ruins and be rebuilt by it. As far back as he could remember, there wasn’t a day he hadn’t thought of it”:

He had pictured it as a blissful place whose inhabitants were graced by God . . . joy reigned in every home. By day, all plowed and sowed and planted and reaped, harvesting their grapes and olives . . . when evening came, they sat beneath their vines and fig trees, each man surrounded by his wife, sons. And daughters. Gladdened by their labors and grateful to be where they were, they thought of their days outside the Land as one thinks of sorrowful times in happy ones and felt doubly blest.

Is this meant to be satirical? Is this a narrator to be trusted for the next six hundred pages? “Agnon was a writer who liked to toy with his readers and never shrank from the risk—indeed, enjoyed courting it—of being misunderstood by them.” The reader is left to ponder if that’s true of Halkin too.

Letters to an American Jewish Friend was reissued in 2013 by the Gefen Publishing House in Jerusalem, with a new introduction by Halkin. The essential truth, he wrote, had not changed: “I loved America for many things, but not for its Jewish life, to which I couldn’t see myself belonging if I remained an American.” Mosaic magazine celebrated the Gefen edition with a symposium: Halkin’s essay, followed by the comments of four respected academics from Israel and America. The latter two took polite umbrage. Responding to the respondents, Halkin praised the

Israeli who had distilled the Letters’ message in a single sentence: “In history, the natural defeats the artificial every time.” Meanwhile, he reassured the American Jewish scholars that by dissing the diaspora he didn’t mean them:

A world without Israel would be as empty for them as it would be for me; the fact that I live there and they don’t is my good fortune, not something I hold against them. . . . In the days before World War II, Zionists spoke of Gegenwartsarbeit or “working in the present.” What this meant to even the greatest sholeley ha-golah or “negators of the Diaspora,” in whose company I number myself, was that even if the Diaspora was (and deserved to be) a lost cause in the long run, everything should be done to strengthen it in the short run, because the stronger it was, the more Zionists there would be in it and the more Jews would leave it for Palestine.

In the “Closing Thoughts” of his new book, Halkin reasserts his lifelong creed:

Secular Zionism was a revolution in Jewish life, perhaps the greatest ever attempted. It sought to change the Jewish people fundamentally. To give it a home. To teach it to defend itself. To get it to take responsibility for itself. To be less bookish and more physical. To think honestly and critically about its situation.

He compares his Hebrew literary heroes with Lucifer, Milton’s “apostate angel of monarchical pride,” rebelling nobly against religion:

There is in them a call for Jewish self-scrutiny and an end to the Jewish illusions they were so familiar with because they had to fight them in themselves—and at the same time, a fierce sense of loyalty to the Jewish people. Even Berdichevsky, as convinced as he came to be that Jewish history had played itself out, couldn’t leave that people behind him. . . . They had great Jewish knowledge, these men. Without a rabbinical education they could never have produced a secular Hebrew literature; without rebelling against the values of this education, they would never have produced it.

Apart from Rahel, “who experienced Zionism with an all-accepting immediacy,” all the writers in the book from Y. L. Gordon onward were both believers and doubters. Was immigration to Palestine feasible? How to deal with the Arabs? Zionism was “simultaneously an affirmation of Jewish history and a repudiation of it.” Ahad Ha’am believed the contradiction could be resolved. Berdichevsky argued otherwise. Gordon, for his part, had warned in his “Zedekiah in the Dungeon” poem:

The smith would leave his forge, the shopkeeper his wares,

To wear haircloth and be soothsayers;

The carpenter’s drills would be beaten into quills,

His chisels into priestly codicils.

Here Halkin pulls no punches:

And meanwhile, the West Bank settlements go on growing. . . . Judea and Samaria are now zones of daily warfare . . . the most zealous settlers and their rabbis set the tone . . . a rabid religious nationalism has invaded the Israeli bloodstream.

That said, it is “preposterous and obscene” to equate Zionism with racism: “It is no more racist to say that the Jews deserve their own country than it is to say that the French do.” But on the other hand: “It is too easy to say that anti-Semitism has nothing to do with who the Jews are or have been. A people can’t go on believing for thousands of years that it is chosen from all the nations and behaving as though it were without incurring resentment.” In summer 2019—so long ago—he writes from Zikhron Yaakov: “The only thing we can definitely expect from the future is that it will be unlike anything we expected.”

He walks on the beach, watches the young wind-surfers, and thinks: “All this soul-searching—all this picking and picking at the Jewish soul—who needs it?” Ideally, it should be Gordon Beach in Tel Aviv, named for Halkin’s hero. Reflecting on his old age in a poem called “Shoresh nishmati”(“The Root of My Soul”), Yalag wrote: “No one knows what must be done; / Solutions there are none. / There is only aggravation / At belonging to this nation.” Or as the Lady of Hebrew puts it: “Tikh’av tamid nishmati / Alai v’al ‘umati.” My soul will always ache for myself and my Jewish people.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?

For the whole history of Jewish society, until less than two hundred years ago, love and attraction played little or no role in the making of marriages, which were arranged and contracted according to the interests—commercial, religious, and social—of the families involved.

A Complex Network of Pipes

You couldn’t know Yehuda Amichai without being struck by the casual way in which original and sometimes startling metaphors dropped from him in ordinary conversation. It wasn’t done for effect. It was just the way his mind worked. One thing made him think of another and what it made him think of was generally something that would not have occurred to anyone else.

Endless Devotion

Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks' new translation of the siddur moves Hillel Halkin to reconsider Jewish prayer.

The Ubiquitous Gabirol

Solomon ibn Gabirol plunges into poetry, writes S. Y. Agnon, medabek atzmo be-charuz: glued to his craft, beading words with devotion.

Jerome M. Marcus

“It is too easy to say that anti-Semitism has nothing to do with who the Jews are or have been. A people can’t go on believing for thousands of years that it is chosen from all the nations and behaving as though it were without incurring resentment.”

I've never understood this particular justification for Jew hatred. Everyone who holds any opinion holds it because he thinks it's correct. If he didn't, he'd hold a different opinion. That's as true for religion as it is for the best way to paint a house.

The Gospel of John has Jesus saying "no-one shall come to the Father but by me" (or Me). Nobody gets mad at Christians, or justifies the hatred or slaughter of Christians, because they believe that, or because it says that in their holy book. Of course they think that: if they didn't think that they wouldn't be Christians. Ditto for Islam's conviction that Muhammad's is the definitive prophecy.

The Enlightenment was supposed to have been the moment when everyone learned to let everyone else live with their own religious truths, as long as they didn't impede anybody else's belief in their religious truth. It seems to have worked pretty well for most people, most of the time, though less well for the Jews than for everyone else. But I see no reason why we, in our own minds and our own books and book reviews, should understand our own religious conviction as any less entitled to respect than anyone else's. It's no justification at all for anti-Semitism. I'm not sure what form of error it is to believe otherwise; but I am sure it is an error.